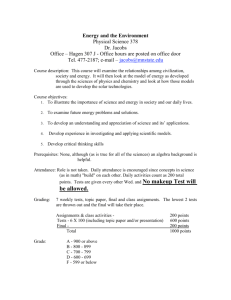

a Visit to Vanity Fair: Moral Essays on the

advertisement

Alan Jacobs, a Visit to Vanity Fair: Moral Essays on the Present Age (Grand Rapids: Brazos Press, 2001), 173 pages. Review by Pastor Nathan, January 2006 **NOTE: I read this book in Sept/Oct of `05, but didn’t get around to writing my interactions with it down until Jan `06. I had seen the recent movie version of Thackeray’s novel, Vanity Fair (and had liked it) and I had read Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress in high school and had a vague memory of Vanity Fair plus I had heard good things of Dr. Jacobs while I was at Wheaton, plus I had seen that his book had received an award from Christianity Today… plus the cover was neat, so I decided to read this book. Overall, I wouldn’t say it’s a must read, but it is an enjoyable read that can be taken in bite-size pieces as it is a collection of individual moral essays in the tradition of Samuel Johnson – a genre of writing well worth reviving in my estimation. Some essays were light and whimsical, even comical. The treatment of the Harry Potter phenomenon titled “Harry Potter’s Magic” is worth reading if you’ve ever seriously asked the question, “Should Christians read Harry Potter?” I also benefited from some of the insight into C.S. Lewis in “Lewis at 100” – did you know that much of Lewis’ fiction is not original? Well, not in the sense that he plagiarized, but he would mimic the imaginations of others and assimilate sources into his own works. “In The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, for instance, the children speak exactly like children in Edith Nesbit’s books; the talking animals come straight out of Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows; the werewolves emerge from the Gothic tradition; and even Father Christmas makes an unexplained appearance” (122). What we many times admire Lewis the most for – his unbound imagination and construction of other worlds – may not actually be his greatest strength. But of the fifteen individual essays, only one really grabbed me. It is titled, “Preachers Without Poetry.” This is because, well, I’m a preacher. It’s what I do. It’s what I have for quite some time seen as the most important item in my job description. So it’s something I think a lot about – “Am I a good preacher?” “Is this working?” “What should preaching look like?” “Is preaching really as important as I’ve thought?” (look for a review of a book I read called Preaching Re-Imagined coming soon). In this essay, Jacobs (a literature professor at Wheaton) is exploring the waning literary quality of the sermon over time. His conclusions are not altogether clear – an intentional ambiguity owing to the literary nature of his essay. But as he gracefully dances in and around this topic his underlining moral judgment is inescapable – while the forces behind the literary decline of the sermon are complex the reality is simply lamentable. One of the causal factors in this noticeable metamorphosis of the sermon Jacobs sees as being the specialization of learning which has resulted in “the copious tangled bronchi of the modern university” (49). There are few Renaissance pastors. In addition, the Romantics further confined the field of literature “in such a way as to exclude almost all polemical or discursive or fact-based writings” (50). This external snub from the literary elites combined with some internal pressure from those reacting against the “metaphorical God” of Donne and others [and, though Jacobs doesn’t say it, I might add the pressures of modernism] have made the sermon more and more aesthetically anemic. In fact, quite often today the Sunday sermon is never even contained in a printed, prose format at all. Now, assuming that the sermon is not altogether passé and a thoroughly modern convention that will soon die out (again see the forthcoming review on Preaching Re-Imagined), I think the presently pervasive inability for sermonizing to attain to some level of art form and the sermon’s current status as only slightly less ephemeral than emails and voice messages is sad. I’ve often felt that homiletics was art. To be a preacher is to be a wordsmith, to be creative, to proclaim the beauty of the Lord in a beautiful way. God is not one dimensional and predictable. He is not flat nor is he reducible to five easy steps or contained in three comprehensive points. Sermons that are dry, flavorless, and merely propositional are a misrepresentation of the mysterious, glorious, ineffable God. That’s what art, be it a poem or novel or moral essay or whatever, does – it gets at the Inexpressible in ways that a textbook cannot. Preachers should strive to be creating good literature. I agree, but I feel inadequate to do this. I think I was doomed by my upbringing and relatively late interest in the vita contemplativa. In my formative years (pre-college) I hated books and would spend consecutive hours in front of the television. Thus my working vocabulary is small and boring. My syntax is simplistic and brutish (had to use my thesaurus for that one). I would never think to describe the fragmentation of learning as “the copious tangled bronchi of the modern university.” I’m afraid that if Jacobs read my sermons he would say what he said of D.L. Moody’s – “[His] style seems so plain, so utterly unadorned, as to be altogether without character. The rhythms are simplistic, the vocabulary limited and colorless; the whole text shuns vivid image or metaphor” (59). Guilty as charged. I want to grow in this. I’m going to keep trying. I don’t want to be a preacher without poetry. I’m grateful for Jacobs’ moral essays, for they are good examples of truth and exhortation packaged provocatively and labeled as literature.