Flexible Working Practices in the UK: Gender and Management

advertisement

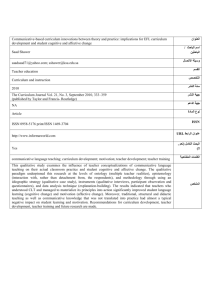

Women in Society Volume 2, Autumn 2011 ISSN 2042-7220 (Print) ISSN 2042-7239 (Online) FLEXIBLE WORKING PRACTICES IN THE UK: GENDER AND MANAGEMENT PERSPECTIVES Karen Jones and Edward Jones, University of Wales, Newport Abstract This article considers some of the implications of flexible working practices, which became an important focus for the UK Government in the 1990s. It examines the potential advantages and disadvantages of flexible working from the organisation’s perspective and that of the worker. Although flexible working legislation and policies are gender neutral, they are often associated with female employees wishing to balance work and motherhood. The paper thus considers the extent to which flexible working is a gender issue and concludes with the assertion that flexible working practices reflect the inequalities that exist in the modern workplace. Keywords: Flexible Working, Implications, Gender, Motherhood Introduction Flexible working practices and indeed the concept of ‘work-life balance’ became an important focus for UK government policy throughout the 1990s, with Lewis & Cooper (2005) believing that this was mainly in response to the work-family pressures experienced by dual earner couples where both parents were employed. Whereas Fagan et al (2006) understood there to be five main drivers that influenced the development of flexible working practices: namely; globalisation; competition and productivity; learning and the knowledge economy; active ageing; the long hours culture and work and caring roles. This view is supported by Faulkner (2001) who believed that the ‘business case’ for flexible working partially revolves around the identification of recruitment pools (e.g. women and older workers) that have yet to be fully exploited. Therefore, this article seeks to explore the nature of flexible working in the UK, identifies the challenges for employers and considers the extent to which flexible working can be seen to be a gender issue. Context ACAS (2011) describes flexible working as :- 1 Women in Society Volume 2, Autumn 2011 ISSN 2042-7220 (Print) ISSN 2042-7239 (Online) …a place of work, for example homeworking, or a type of contract, such as a temporary contract. Other common variations include: part-time working; flexitime; job sharing; and shift working. Hill et al (2001) described flexibility as including a range of practices such as flexitime, flexispace, job sharing and homeworking. Indeed, it could be argued that any variation outside of working 9-5, Monday to Friday, at a fixed location should be classed as flexible working. For example, working from home is more common across industries, and these practices are made possible due to advances in mobile technologies (Strategic Direction, 2008). However, Lewis & Cooper (2005) argued that although in principle flexible working can take many forms, the predominant flexibility that UK employers offer is that of reduced working hours. Legislation and Flexible Working in England and Wales The evolution of flexible working within England and Wales has been facilitated by many changes in employment legislation that support employees, allowing them, for example, to have the right to request a flexible working pattern. McIntyre (2007) highlighted the importance of the Employment Rights Act 1996 as a major piece of legislation supporting parents to the right to request flexible working. Other regulations such as the Working Time Regulations (1998), the Equality Act (2006) and the Disability Discrimination Act (1995) also support flexible working for eligible employees. In the UK, the right to request, and duty to consider flexible working was introduced in April 2003 to provide employees with parental responsibility for children under the age of six (or 18, if disabled) with a right to request a change in how many hours, when or where they work, and to have such a request seriously considered by their employer. In April 2006, the coverage of this right was extended to employees who care for a dependent adult; a second extension, from April 2009, extended coverage to parentsof children under 16. Further extensions were initially planned, taking the age limit to 18, but this was later repealed as a result of the economic climate. Perhaps, such legislation lead to the assertion of Lewis and Cooper (2005) that a reduction in hours is often the only type of flexible practice on offer; however, the ONS table below appears to indicate that this is not necessarily the case and other flexible working patterns are available. 2 Women in Society Volume 2, Autumn 2011 ISSN 2042-7220 (Print) ISSN 2042-7239 (Online) Employees with Flexible Working Patterns, by Sex and Type of Employment, 2009 Men Women Flexible working hours 10.9% 15.3% Annualised working hours 4.9% 4.9% Term-time working 1.2% 6.7% Four and a half day week 1.2% 0.5% Nine day fortnight 0.5% 0.4% Any flexible working pattern 19% 28.1% Flexible working hours 8.6% 10.3% Term-time working 3.6% 11.6% Annualised working hours 3.3% 4.6% Job sharing 1% 2.1% Any flexible working pattern 18.4% 29.6% Full-time employees Part-time employees Source: National Statistics (2010). Social Trends 40: 2010 edition. Newport: National Statistics. Available from:http://www.statistics.gov.uk/downloads/theme_social/SocialTrends40/ST40_Ch04.pdf Holt & Grainger (2005), in a survey commissioned by the DTI, described how the awareness of the right to request flexible working has increased since its introduction in 2003. It was found that almost a quarter of employees who were eligible to make a request to work flexibly had actually made a request in the past two years. They also reported that the rate of refusals had almost halved since the right was introduced with one in five employees reporting that they had taken time off to care for someone in the past two years. 3 Women in Society Volume 2, Autumn 2011 ISSN 2042-7220 (Print) ISSN 2042-7239 (Online) Gender and the Right to Request Despite this favourable picture regarding the increase in awareness and requests made and accepted, there is an argument that gender and position in the organisation is pertinent to the right to request discussion. Lewis et al (2007) believed that the concept of flexible working practice is difficult to separate from socially embedded beliefs relating to the actual roles that fathers and mothers are expected to play. Therefore, although government policy, strategy and rhetoric in this area refers to ‘parents’ and are on the surface presented as gender neutral, the reality is that these policies were initially conceived with women and motherhood in mind. Fagan et al (2006) were concerned that as policy seemed to focus upon work-family reconciliation, then flexible working hours have become associated with the ‘mummy track’. They stated that: large numbers of women work part-time, where a high and persistent part-time pay penalty is incurred. Part-time work has often been created explicitly to recruit or retain women, while the continuing workplace expectation that long hours are to be worked in particular jobs such as management helps to preserve this area of employment as a largely male enclave (pg. 7). It is difficult to obtain up-to-date data regarding actual gender splits for right to request applications. However, other information sources seem to indicate that reduced hours are predominantly associated with mothers. For example, a 2009 CIPD survey indicated that working in excess of 46 hours per week (including evenings, nights and weekends) was commonplace for many fathers with children under 14, with 39% of fathers surveyed reporting working more than 60 hours. Additionally, Hegewisch (2009) explained that although both men and women are requesting flexible working, women are much more likely to make requests for childcare reasons. Furthermore, it was noted that part-timers have been particularly likely to (successfully) request flexible working, thus suggesting that often such requests come from women. Prior to this research, a 2006 survey (Fagan et al) demonstrated that although significant numbers of men have requested flexible work, they then experienced greater barriers to their requests than women. In essence, it was argued that men were more likely to have their requests rejected by their employer (14% of men compared to 10% of women) and also more likely to have their cases turned down in the employment tribunals. Hegewisch (2009) also discovered that employees in managerial jobs, across Europe, were far less likely both to request reduced hours and have 4 Women in Society Volume 2, Autumn 2011 ISSN 2042-7220 (Print) ISSN 2042-7239 (Online) their request accepted. As Fagan et al (2006) (see above) asserted that men were far more likely to be incumbent in managerial jobs, then this could be seen as discriminatory. Indeed, Hegewisch (2009) believed that male employees are actually disadvantaged by the ‘soft’ framing of the Right to Request because, unlike women, they are unable to claim that lack of flexibility indirectly discriminates against them as a group and consequently may only challenge employers’ refusals on procedural grounds, not substantively (pg. 11). The Employer and Flexible Working Advocates of flexible working would be keen to highlight the benefits of such practices for the employer, but it should be acknowledged that flexible working also brings management and organisational challenges. Sholarios and Marks (2004), (as cited by Bratton & Gold, 2007, pg.149) suggested that in this highly competitive labour market, in order to attract and retain staff, work-life policies and procedures are a must for any organisation. Strategic Direction (2008) explained that organisations that take a strategic view of flexible working practises are more likely to succeed and flexible working should be viewed as a business tool which in turn allows employers to get more value from their best asset; the employee. The Managerial Law Review (2006, pg.536) concurred that success in a business environment involves having a flexible workforce in order to meet changeable demands. Planned flexible working projects can bring many benefits to an organisation for both the employee and organisation, such as improved performance on service delivery and customer satisfaction, efficiency savings, reduced recruitment and improved retention, improved employee morale, increased productivity and overall positive impact on the working environment (Strategic Direction, 2008, pg.9). In contrast, Hall & Atkinson (2006) suggested that flexible working whether formal or informal, is merely another management control in disguise, as workers who feel empowered and valued in the workplace will produce a higher standard of work and allow workers to take on more responsibility. Whilst the empowerment moves the control from the manager to the employee, this often results in more pressure on the employee to perform. Professional bodies have asserted that flexible working can assist both organisations and workers in organising work more effectively and thus reducing stress at work. For example, the CIPD’s surveys on flexible working showed that flexible working has had a positive effect on absenteeism, staff retention, staff morale and employee relations, subsequently creating a positive impact on productivity and profits (CIPD 2003 and 2005). 5 Women in Society Volume 2, Autumn 2011 ISSN 2042-7220 (Print) ISSN 2042-7239 (Online) Johnson (2004) asked the question when traditional ways of working are changed, what happens to the traditional way of managing performance and staff within the workplace? As more staff via away from a traditional working day, although this means greater flexibility, it also leads to challenges for both the employer and employee to create a working relationship that suits both parties. Johnson argued that line managers will have to learn new ways of thinking in order to derive new attitudes and behaviours. This puts added pressure on to managers, as their role will also need to become more flexible and multi-faceted in order to plan, implement and manage these changes effectively. Within organisations where flexible practices are granted, hierarchical management structures may not be best suited. Managers may need to adopt very different roles such as planning, coaching and also more effective leadership. Objectives would need to be made clear and transparent in order that staff can perform both in work and away from the workplace. Hall and Alkinson (2006) reported that for many employers, an informal arrangement for flexible working is usually favoured as it gives the employee a false sense of control. They argued that informal negotiation is evident throughout many organisations and usually involves some form of negotiation between the manager and employee, but allows management persuasion at times. Such informal agreements allow managers to review the situation regularly and allow greater flexibility than a more formal application process. As many staff are unsure what flexibility they are actually entitled to, this management style allows managers to appear accommodating, whilst giving the employee some control over their working time but in an informal manner, allowing for boundaries and control to still be present. However, although this informal, practical approach may be favoured by both employees and employers, it should not be in breach of employment legislation that grants employees rights, such as the right to request flexible working. There are also specific difficulties for SMEs when introducing flexible working practices. Maxwell et al (2007) explained that within smaller businesses, there is not always a Human Resources department on hand and there are usually very informal approaches to Human Resources in general. It is very common for smaller businesses to have an owner/manager structure and the need to balance both formal and informal practices in line with employment law, along with maintaining flexibility, is not always viable. Union presence is sometimes non-existent within smaller firms and employees are not always aware what they are entitled to and how HR policies fit in with their everyday role. 6 Women in Society Volume 2, Autumn 2011 ISSN 2042-7220 (Print) ISSN 2042-7239 (Online) Work Life Balance and Home Working The discussion above has touched upon the concepts of work life balance and family friendly policies, terms that will now be discussed more fully. Work-life conflict is a term that relates to the interference that one’s working life has on one’s personal life. Messersmith (2007, cited in Perkins & White 2008) believed that an imbalance between work and an employee’s other activities will cause the employee to eventually stop thinking about their employment at all and may even lead to long term sickness or absence. It could be argued that it is in the manager’s best interest to resolve these issues by establishing ‘family friendly’ policies. However, Griffiths et al (2005) argued that although business and policy discussion seems to frame work life balance in terms of family friendly or female friendly workplaces, nothing much can be done to challenge the inequality long connected with domestic and caring responsibilities. Gatrell (2005) sympathised with this viewpoint, believing that although fathers may wish for equality in terms of parenting, this does not necessarily mean that they also want equality in terms of domestic labour. Indeed he believed that most men preferred to cast themselves in the role as ‘helper.’ Brugel& Grey (2005) found that men’s domestic and caring contribution did increase as women devoted more time to employment (although not necessarily proportionately); perhaps supporting the view that a reduction in working hours for women may merely lead to an increase in domestic responsibility. Barnett et al (2010) studied this issue in depth and concluded that: Mothers may find it distressing then if more ‘involved’ flexible fatherhood’ still allows men to partake in unencumbered contact with children, whilst they are obliged to ‘mop up’ the additional domestic chores. So, whilst it may indeed be a particularly hard time to be a father, it seems the pressures associated with the budding desires to flexibly navigate the cultural expectations of being a good employee and a good dad are very much predicated upon the expectation of, unsung, maternal support (pg. 16). In the light of the above discussion, the case for home working improving work life balance issues is at best mixed. Messersmith (as cited by Perkins & White, 2008) argued that although working from home or ‘virtual’ working practices benefit the employee and to the employer to some extent, there are reported downsides. Messersmith believed that once the boundary between work and personal life is removed, it is more likely that levels of work-life conflict will be introduced, as the employee is kept ‘out of the loop;’ and loses links with colleagues and the workplace. Secondly, this way of working will only be successful if the 7 Women in Society Volume 2, Autumn 2011 ISSN 2042-7220 (Print) ISSN 2042-7239 (Online) employee is willing to invest in new technologies in order to access work systems from home and finally, there is a risk that staff who work in isolation may miss out from any development or promotion opportunities that may arise. Furthermore, Wilson and Greenhill (2004) asserted that home working ignores the fact that being available to both your employer and family may actually be mutually exclusive leading to increased conflict between work and home. Conclusion This article has emphasised some of the implications of flexible working practices for employers and employees. From the employer’s perspective, allowing employees to work in a flexible manner can increase performance and productivity, increase efficiency savings and improveretention. Flexible working also benefits employees, as they have the opportunity to better manage the work-life balance and can experience higher levels of morale. Although flexible working can benefit the worker and the organisation, it also presents both parties with a number of challenges. For example, the employer may have to rethink his or her management style, particularly if the employee is working from home, whilst the employee will require selfdiscipline and, if he or she is working from home, the ability to work alone and to access and utilise appropriate technology. It should not therefore be assumed that flexible working will suit all employers and employees. Although flexible working legislation was drafted in gender neutral terms, it was conceived with women in mind. Indeed, data demonstrates that women are more likely to request flexible working than men and are also more likely to have their request granted. One of the reasons why men make fewer requests for flexibility and more often have their request rejected, is that men are more likely to be in management positions that do not lend themselves to reduced hours or working away from the office. In addition, flexible working has become associated with the ‘mummy track’ which itself may deter male employees from making a request. Flexible working practices thus highlight equality issues that are ever present in the modern working environment. REFERENCES ACAS, 2011.http://www.acas.org.uk/index.aspx?articleid=1616 accessed 04/04/2011 Blakebeard, S., O’Neill, R., Ingols, C. & Shapiro, M. 2010. Social Sustainability, Flexible Work Arrangements and Diverse Women. Gender in Management: An International Journal. 25(5), pg. 408-425 8 Women in Society Volume 2, Autumn 2011 ISSN 2042-7220 (Print) ISSN 2042-7239 (Online) Bratton, J. and Gold, J. 2007. Human Resource Management, Theory & Practice.4thEdn. Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan Bruegel, I., and Grey, A. 2005. “The future of work and the division of childcare between parents” in Houston D. (ed.) Work/life Balance in the 21st Century London: Palgrave Burnett, S.B. 2011. http://www.workingfamilies.org.uk/admin/uploads/Chapter%20%20Fatherhood%20and%20FWP.pdf Carlson, D., Grzywacz, J. and Kacmar, K. 2010. The Relationship of Schedule Flexibility and Outcomes via the Work-Family Interface.Journal of Managerial Psychology.25(4), pg. 330-355 CIPD. 2003. “A parent’s right to ask: A review of flexible working arrangements” available from http://www.cipd.co.uk/subjects/wrkgtime/flexwking/prntrighttoask.htm?IsSrch Res=1 CIPD. 2005. “Flexible working: Impact and implementation - An employer survey” London: Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development, February: London CIPD, 2011.http://www.cipd.co.uk/search/searchresults.aspx?recommended=True &Query=flexible+working&PageIndex=1&sortby=relevance&sitetype=REDE SIGN_MAIN accessed 10.04.11 Contractor UK, 2011.http://www.contractoruk.com/news/002859.html accessed 13.4.11 Department of Social Protection (Ireland) 2011.http://www.welfare.ie/EN/Publications/work_fam/Pages/chapter3.aspx accessed 12.4.11 Fagan et al, 2006. http://www.tuc.org.uk/extras/outoftime.pdf Faulkner, F. 2001 ‘The technology question in feminism: A view from feminist technology studies’, Women's Studies International Forum, Vol. 2, No.1, pg.79-95. 9 Women in Society Volume 2, Autumn 2011 ISSN 2042-7220 (Print) ISSN 2042-7239 (Online) French, J., Andrew, J., Awramenko, M. and Coutts, H. 2005. General Practitioner Non-principals Benefit from Flexible Working.Journal of Health Organization Management.19(1), pg. 5-15 Gibson, V. and Luck, R. 2004.Flexible working in Central Government: Leveraging the benefits.Department of Real Estate & Planning University of Reading Business School Griffiths, M., Moore, K.And Richardson, H. 2005. Gender on the Agenda: Flexible Working and the Work-Life Balance in the UK ICT Industry http://www.iris.salford.ac.uk/GRIS/winit/Publications/WINIT_Gender_on_the _Agenda_corrected_version.pdf Hall, L. and Atkinson, C. 2006. Improving Working Lives: Flexible Working and the Role of Employee Control. Employee Relations. 28(4), pg. 374-386 Hegewisch, A. 2009.http://www.equalityhumanrights.com/uploaded_files/research/16_flexib leworking.pdf Hill, E.J., Hawkins, A.J., Ferris, M. & Weitzman, M. 2001. ‘Finding an Extra Day a Week: The Positive Influence of Perceived Job Flexibility on Work and Family Life Balance’ Family Relations, 50(1): pg.49-58. Holt, H. and Grainger, H. 2005. Results of the second flexible working employeesurvey, Department of Trade and Industry Employment Relations Research Series No. 39. London DTI Johnson, J. 2004. Flexible Working: Changing the Managers Role. Management Decision. 42(6), pg. 721-737 Kattenbach, R., Demerouti, E. and Nachreiner, F. 2010.Flexible Working Times: Effects on Employee’s Exhaustion, Work Nonwork Conflict & Job Performance. 15(3), pg. 279-295 Lewis, S. and Cooper, C.L. 2005. Work-Life Integration: Case Studies of Organizational Change, Chichester: Jon Wiley and Sons. Lewis, S., Gambles, R., &Rapoport, R. 2007. ‘The Constraints of a Work-life Balance Approach: an International Perspective’ The International Journal of Human ResourceManagement, 18(3) pg.360 – 374. 10 Women in Society Volume 2, Autumn 2011 ISSN 2042-7220 (Print) ISSN 2042-7239 (Online) Lewis, S. and Humbert, A.L. 2010. Discourse or Reality?Work Life Balance, Flexible Working Policies and the Gendered Organization.Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal. 29(3), pg. 239-254 Marchington, M. and Wilkinson, A. 2007. Human Resource Management at Work.3rdEdn. London:CIPD Maxwell, G., Rankine, R., Bell, S. and MacVicar, A. 2007. The Incidence and Impact of Flexible Working Arrangements in Smaller Businesses. Employee Relations. 29(2), pg. 138-161 McIntyre, E. 2007.Business Law. 3rdEdn. Essex: Pearson ML, 2006. Flexibility and the Workplace: The Battle to Control Working Time. Managerial Law. 48(6), pg. 536-540 National Statistics, 2010.Social Trends 40: 2010 edition. Newport: National Statistics. Available from: http://www.statistics.gov.uk/downloads/theme_social/SocialTrends40/ST40_Ch04.pdf Perkins, J. and White, G. 2008. Employee Reward Alternatives, Consequences and Contexts. 1stEdn. London: CIPD Sparrow, P. and Hiltrop, J. 1994.European Human Resource Management in Transition.Essex: Pearson Strategic Direction, 2008.Flexible Working as Human Resources Strategy.Strategic Direction. 24(8), pp. 9-11 Wilson, M. and Greenhill, A. 2004. ‘A critical deconstruction of promises made for women on behalf of teleworking’, 2nd International Critical Reflections on Critical 11