Document

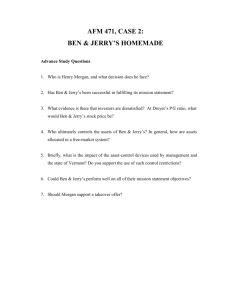

advertisement

Business Policy Issue Study April 1, 2003 Stephanie Straub Cindy Sellers Ivicia Simac Sally Yu Ben & Jerry’s and Japan 2 Company History Ben Cohen and Jerry Greenfield met as children growing up in Vermont. After being schoolmates in Brooklyn, New York they decided to open an ice cream company. They turned around an old beat up gas station located in South Burlington, Vermont into their new site of business in 1978. Ben and Jerry, both children of the sixties, wanted to start a company that reflected their anticorporate style. The company grew quickly, partially due to their catchy flavor names and extra chunky ingredients. Ice cream was sold by the scoop, but soon was demanded by the pint. By 1984 they had taken the company public in Vermont. Not long after, they registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), allowing for the nationwide purchase of their stock.1 Ben and Jerry were both good ‘ol boys from Vermont who conducted their stockholder meetings more similar to a festival than a typical corporate meeting. These men showed that their company was not only a great place to work, but was also socially responsible to their community. They believed in something they called ‘caring capitalism’ and donated 7.5 percent of pretax profits to social causes including Healing Our Mother Earth and Center for Better Living.2 Their product, superpremium ice cream, is exceptionally rich. The butterfat content of their ice cream was at least 12%, compared to the 6-10% of normal ice cream, and was very dense. To ensure quality and to maintain community roots, Ben & Jerry’s would only purchase cream from local Vermont dairies.3 Haagen-Dazs, their largest competitor, promotes a very sophisticated image targeting an elite class of ice cream buyers. Ben & Jerry’s funky image appealed to a younger crowd with a more caring eye. Their commitment to a social mission is obvious in their mission statement, quoted from http://www.benjerry.com/mission.html: Sellers, Simac, Straub, & Yu Ben & Jerry’s and Japan 3 BEN & JERRY'S IS DEDICATED TO the creation & demonstration of a new corporate concept of linked prosperity. Our mission consists of three interrelated parts. UNDERLYING THE MISSION is the determination to seek new and creative ways of addressing all three parts, while holding a deep respect for individuals inside and outside the company, and for the communities of which they are a part. Product To make, distribute and sell the finest quality all natural ice cream and related products in a wide variety of innovative flavors made from Vermont dairy products. Economic To operate the Company on a sound financial basis of profitable growth, increasing value for our shareholders, and creating career opportunities and financial rewards for our employees. Social To operate the Company in a way that actively recognizes the central role that business plays in the structure of society by initiating innovative ways to improve the quality of life of a broad community local, national, and international. Underlying the mission of Ben & Jerry's is the determination to seek new & creative ways of addressing all three parts, while holding a deep respect for individuals inside and outside the Company and for the communities of which they are a part. International Expansion Ben & Jerry’s has attempted to enter many foreign markets. Most have been entered with little attention focused on strategy. Ben Cohen did not believe in expanding his business just to allow it to grow. This made for a late entry into foreign markets, since when moves were made internationally it was mainly due to an opportunistic Sellers, Simac, Straub, & Yu Ben & Jerry’s and Japan 4 encounter that came about through friends of the founders. By 1997 Ben & Jerry’s international sales and domestic sales were drastically lower than their main competitor, Haagen-Dazs, which had substantial international expansion. Ben & Jerry’s had domestic sales of $174 million and foreign sales of $6 million; however, Haagen-Dazs’ domestic sales totaled $400 million with foreign sales of $700 million.4 Haagen-Dazs was annihilating Ben & Jerry’s in sales both domestically and abroad. 1997 Sales Domestic Sales Ben & Jerry’s Haagen-Dazs $174 million $400 million Foreign Sales $6 million $700 million In Ben & Jerry’s eighth year, the company first went international through a licensing agreement in Canada. A Canadian firm was given all rights to manufacture and sell the ice cream. Canadian tariffs were up to 15% and there was a quota of only 347 tons annually that could be imported. This was troublesome because one-third of the product was imported from the US. By 1992 the Canadian license was repurchased. In 1997, Quebec was left with just four scoop shops.5 Ben & Jerry’s decided to enter Israel by giving Ben’s friend, Avi Zinger, a manufacturing license in 1988. They performed no strategy or field-testing; they simply burst into the market. Sales in 1997 amounted to $5 million, however the only profits Ben & Jerry’s saw from that was the licensing income, which is considered negligible. The fourteen scoop shops left in Israel were selling items such as gifts, baked goods, and beverages in addition to ice cream.6 In 1995 CEO Bob Holland was very excited about entering the French market. The product was sent off to a major retailer of which Ben had met through a Social Sellers, Simac, Straub, & Yu Ben & Jerry’s and Japan 5 Venture Network ties. Turmoil grew in France when protests grew over French nuclear testing. Ben & Jerry’s considered pulling out of France, but instead stayed and put no effort into marketing or promoting and did not attempt to address French labeling laws. However, the company did hire out a French public relations firm and contracted with a sales and distribution company to help ease the entry of their product. The problem is that these firms worked without a single representative from Ben & Jerry’s. Sales in 1997 amounted to a meager $1 million.7 Overall Ben &Jerry’s has entered foreign markets without the consensus of the board and without the necessary headquarters staff to put together any kind of comprehensive plan. They did have experience in the foreign markets, but continued to not learn from their mistakes. Given Ben & Jerry’s track record, it makes no sense to commit to entering the superpremium ice cream market in Japan. In the past their anticorporate style and lack of strong management has harmed them when entering foreign markets. A well-developed strategy should be formed before entering the Japanese market. The Japanese Market The benefits of entering the Japanese market include the large market and overall profit increases. Ben & Jerry’s will gain more customers by going to Japan, which is the world’s second largest ice cream market.8 This will increase sales and perhaps prove to be a long-term growth option. Ben & Jerry’s can utilize their excess manufacturing capacity in the U.S. and export the product to Japan which would result in lower costs as economies of scales were exploited. They can charge higher prices for their product, since the Japanese are willing to pay more to cover the costs of exporting.9 However, Sellers, Simac, Straub, & Yu Ben & Jerry’s and Japan 6 there are some downfalls to entering the Japanese market. Haagen-Dazs (owned by Pillsbury) has established itself as the superpremium ice cream in Japan. It would be difficult to compete with such a prominent brand name with such large resources. The entry costs of expanding into the Japanese market are high. The venture would not be the result of satisfying their social mission or catering to a market of demanding customers. Many substitutes for the product exist and the packaging and ingredient specifications would have to be changed. Ben & Jerry’s had recently renewed their ambitions of social missions in the dayto-day operations. However, Japanese consumers do not care about social objectives.10 Also, customer satisfaction is very important to a Japanese business (and its patrons). Keeping up on customer satisfaction would entail constantly reevaluating and responding to comply with the customer’s demands. Many substitutes available for their product may increase the elasticity of the demand function, since the product competes against all other snacks, not just other desserts (especially considering that it is a luxury item). The Japanese consumers may be more price conscious than expected because of this, especially considering that the Japanese economy was not doing well in 1997. As can be seen from Appendix I, the economic growth rates were below zero for the first time since 1974 in 1997.11 Their GDP (and GDP per capita) were steadily declining, while bankruptcies were increasing.12 The crisis from Thailand’s currency devaluation is spreading across Asia, with the potential to affect Japan.13 Haagen-Dazs is not exposed to this currency risk as much because half of its manufacturing facilities are in Japan. Lastly, Ben & Jerry’s would have to alter their product by changing the packaging and decreasing the size of the chunks in the ice cream.14 Sellers, Simac, Straub, & Yu Ben & Jerry’s and Japan 7 Ben & Jerry’s Ability to Enter Japan Ben & Jerry’s have several strengths and competitive assets to support their entry into the Japanese market of premium ice cream. They have high differentiation in a great variety of styles and flavors that we anticipate to be very attractive for Japanese people. Ben & Jerry’s is a multinational corporation with many experiences in foreign markets, although none were very strategically executed. They have excess capacity in manufacturing in U.S. plants, which will lower the cost since they can export their product to Japan with lower cost than producing the same product in Japan.15 Quality control is very high in manufacturing process that every product needs to be the same with the identical amount of ice cream and chunks. They donate 7.5% of pretax profits to social causes, which gives them a great reputation in society.16 Ben & Jerry’s have established strong brand name image and company awareness worldwide. Some of the weaknesses that Ben & Jerry’s posses are poor and unmotivated management, frequent changes of CEO’s within the corporation, and a lack of clear strategy direction.17 Ben & Jerry’s profit sanctuaries are small compared to their biggest competitor in Japan, Haagen-Dazs. Few options considered thus far have allowed them to promote the brand name and quality of their product in Japan on a level to compete with the brand awareness that Haagen-Dazs has built up. Last but not least, they have yet to develop a strategy for international expansion. Haagen-Dazs in Japan Haagen-Dazs’ presence in Japan is both an advantage and a disadvantage from Ben & Jerry’s perspective. Haagen-Dazs is the main competitor of Ben & Jerry’s in the US market and it has almost the entire superpremium ice cream market share in Japan.18 Sellers, Simac, Straub, & Yu Ben & Jerry’s and Japan 8 Haagen-Dazs is not only popular in Japan, but it is also well established. If Ben & Jerry’s were to enter the Japanese market, it would be almost ten years behind HaagenDazs. Also, Haagen-Dazs had $300 million of estimated sales in Japan alone, compared to Ben & Jerry’s worldwide sales total of $150 million.19 This may make it difficult for Ben & Jerry’s to compete with Haagen-Dazs, which had captured almost half the superpremium market in Japan. Ben & Jerry’s insisted to export their product to Japan from its plant in Vermont, which limited its choice to sell its products. Unlike Ben & Jerry’s, which would export the products, Haagen-Dazs began production at a plant owned jointly by Haagen-Dazs, Sentry, and Takanashi Milk Product in Japan.20 This allowed Haagen-Dazs to gain another 25 percent sales from scoop shops.21 By producing its products in Japan they avoided the risk of negative exchange rates and the cost of shipping and tariffs, which allowed Haagen-Dazs to produce its product at a lower cost and therefore were more competitive on its price. Haagen-Dazs’s successful entry into the Japanese market allowed it to build up its brand capital. This in turn allowed it to use a wide range of marketing channels. So again it may be difficult for Ben & Jerry’s to compete with Haagen-Dazs, which has gained the initial brand loyalty from consumers. Ben & Jerry’s has to work hard to differentiate its image from other superpremium ice cream so that the Japanese people would not think of Ben & Jerry’s as just another superpremium ice cream. However, Haagen-Dazs’ presence in Japan also helps Ben & Jerry’s get into the Japanese market to a certain extent. Haagen-Dazs has successfully established a superpremium ice cream market in Japan. This means that Ben & Jerry’s does not need to educate the consumers on the advantages of buying a superpremium ice cream. Sellers, Simac, Straub, & Yu Ben & Jerry’s and Japan 9 Haagen-Dazs has established the underpinnings of the market, Ben & Jerry’s would need only to convince consumers to switch products. Also, it saves Ben & Jerry’s from some market research. Haagen-Dazs’s flavors in Japan were basically the same as those in the United States, with some slight modifications to fit Japanese tastes.22 With that information, Ben & Jerry’s now has an idea about how they can adjust their product to please the Japanese market. Export Strategy Risks and Costs There are certain risks that Ben & Jerry’s may encounter when they choose to export their product from the plant in Vermont to Japan. These risks include exchange rate risks, commodity risks, high tariffs, administrative costs, middlemen and transportation costs, and the costs and risks associated with changing the packaging. Exchange rate risk is a factor because of the appreciation of the US dollar to the Japanese Yen and how that would make the Ben & Jerry’s product more expensive, and hence less competitive than local products or products produced in Japan directly. This also makes Ben & Jerry’s financial picture less predictable. Commodity risk is a concern for Ben & Jerry’s because the price of milk and other dairy products could decrease in Japan, giving companies with production facilities in Japan a cost advantage.23 Of course, the price of tariffs and administrative costs associated with exporting are definitely a factor.24 The current tariff is 23.3%, but it is scheduled to decrease to 21% in 2000.25 The administrative costs to obtain an exporting license, etc. would be minor, but should be considered nonetheless. A major barrier to exporting to Japan is the high costs associated with the multilayer distribution system in Japan. Not only would physically shipping the product to Japan be costly, but getting it through the infamous Japanese distribution Sellers, Simac, Straub, & Yu Ben & Jerry’s and Japan 10 system would also be a costly challenge. However, the option of partnering with 7Eleven would enable Ben & Jerry’s to circumvent this cost. This is explained in more detail in the next few pages. Lastly, the products exported to Japan would carry a different label even though they were still produced in the Vermont plant.26 This means that the products would only be suitable for distribution in Japan and nowhere else. The production orders would have to be carefully monitored and filled in order to decrease any surpluses or shortages of the product for export. It is crucial for Ben & Jerry’s to control the shipping time. When the distributors adapt the just-in-time inventory procedures, it will make delivery reliability especially key. 7-Eleven Option 7-Eleven has proposed that Ben & Jerry’s export their ice cream directly to the 7Eleven stores in Japan.27 This would allow Ben & Jerry’s to bypass the notorious Japanese distribution system, since 7-Eleven would take care of the distribution of the product. Other than the costs and risks of export strategy outlined above, there are benefits and risks to consider that are specific to the 7-Eleven proposal. The primary benefit of partnering with 7-Eleven is ease of distribution to many successful stores. However, there are also many costs and risks. 7-Eleven is known for having high demands from its producers, and partnering with 7-Eleven Japan would give 7-Eleven considerable bargaining power. Brand awareness is an issue to consider, along with the fact that social objectives are not a concern for 7-Eleven. By partnering with 7-Eleven, Ben & Jerry’s could sell directly to the convenience stores and avoid Japan’s complex distribution system.28 This would lower costs, providing a larger margin to help cushion export, currency, and commodity risks. Sellers, Simac, Straub, & Yu Ben & Jerry’s and Japan 11 Furthermore, the ice cream would automatically be distributed to over 7,000 convenience stores.29 This is significant because convenience stores accounted for at least 40% of the superpremium ice cream sales in Japan, and had experienced a higher annual growth of market share (8.3%) than supermarkets and outlets.30 Among Japanese convenience stores, 7-Eleven has a good brand image, and was experiencing rapid growth with an 8.2% increase in sales from 1997 to 1998.31 Of course, there are concerns with the potential partnership, too. 7-Eleven has already made some demands that could compromise Ben & Jerry’s position, and 7Eleven has a history of being very difficult. Ben & Jerry’s executive discovered that Dreyer’s, the company that distributed Ben & Jerry’s in the US, had trouble meeting the demands of 7-Eleven Japan just a couple years earlier. The just-in-time deliveries required large inventories, but 7-Eleven wanted to be able to quickly drop varieties that did not sell well.32 This ultimately led to the demise of the partnership. The same thing could easily happen to Ben & Jerry’s. Already, 7-Eleven insisted that the product be sold in 120 ml cups instead of the 473 ml pints that B&J’s currently produce.33 Japanese consumers do seem to prefer the individual servings, but the cost of switching to the production of small cups would be about $2 million.34 They would have to decrease chunk size to fit the smaller cups as well. Moreover, 7-11 wanted control over the package art, something that had been a distinguishing factor of the ice cream in the past.35 A critical factor to discuss is that 7-Eleven wanted to sell Ben & Jerry’s for slightly less than Haagen-Dazs, which would convey the message that Ben & Jerry’s was of lower quality.36 It would already be difficult to build up a brand name to compete with Haagen-Dazs since the only visibility Ben & Jerry’s would have is on a convenience store shelf next to other ice creams Without brand capital, it would be difficult to expand Sellers, Simac, Straub, & Yu Ben & Jerry’s and Japan 12 beyond 7-Eleven. If Ben & Jerry’s is priced lower than Haagen-Dazs, what little brand awareness built up would convey that Ben & Jerry’s is inferior to Haagen-Dazs, making it nearly impossible to sell in Japan outside of 7-Eleven. Furthermore, the partnership would result in 7-Eleven having considerable bargaining power over Ben & Jerry’s. 7Eleven US was Ben & Jerry’s largest retail outlet.37 Although Ben & Jerry’s was one of 7-Eleven’s largest customers, the balance of power would still be with 7-Eleven. This difference in bargaining power combined with the specific demands that 7-Eleven has and could request may well be lethal. One of Ben & Jerry’s largest concerns was that social objectives were not of concern to 7-11, nor did moving the product there meet the new objective of bettering the world in the day-to-day operations.38 However, day-to-day operations would be impossible if profits were not made, and if profits were not made, nothing could be donated to charity. Japan might make those profits. This and other factors leaves the 7Eleven option on the table, but not as a clear choice. Partnering with Yamada Yamada, the entrepreneur that successfully brought Domino’s to Japan, has also offered to distribute Ben & Jerry’s ice cream. However, Yamada’s proposal is not as detailed as 7-Eleven’s, because Yamada does not want to commit resources to the project until he is confident it will take place.39 A partnership with Yamada could offer many factors to Ben & Jerry’s. Yamada would provide instant expertise of the market, he could use Domino’s for market testing, and he could orchestrate and implement the expansion into Japan. There are two main disadvantages of a potential partnership with Yamada. He has insisted on full rights to the Japanese market and he has no ambition to institute a Sellers, Simac, Straub, & Yu Ben & Jerry’s and Japan 13 social mission.40 An analysis of this option shows that the benefits do not outweigh the costs. It is true that Domino’s is very successful, and that they already offers ice cream cups.41 This would it make it easy to do market testing through the company. Yamada is also very experienced in the Japanese market, and there is no doubt that he is very skilled at brining American companies into Japan. Once he took over, Ben & Jerry’s would have to do very little – Yamada would take full responsibility for orchestrating and implementing the plan. However, the costs are substantial. Yamada has insisted on the full rights to the Japanese market, and would want final say over all branding and marketing efforts in Japan.42 Branding and marketing have been key to Ben & Jerry’s success elsewhere; the final say for these undertakings should be kept inside the company. Furthermore, no social mission would be put into place. This is significant because Ben & Jerry’s commitment to social objectives is a differentiating factor for them, especially compared to Haagen-Dazs. It is also a concern that since Yamada would hold full rights to the market, he could change the agreement in the future. It is possible that he could sacrifice their quality image, marketing them as less prestigious than Haagen-Dazs. However, this is not the only factor that results from the releasing of the rights to the Japanese market. If Yamada retained full rights to everything, it is questionable whether or not Ben & Jerry’s would take away any knowledge. It would just be too easy to give all the responsibility to Yamada and walk away from the strategic picture. This could be detrimental to their long-term need to develop skills and capabilities to enter other foreign markets. Sellers, Simac, Straub, & Yu Ben & Jerry’s and Japan 14 Delaying the Choice Ben & Jerry’s could always choose to take more time to consider their other options. This would prevent them from jumping into a partnership that could eventually be hazardous. Bartlett & Ghoshal warn that companies often fall into the “quick and easy” option of a partnership, believing it is the only option available. This is especially true in situations where a partnership might provide a “façade of recovery that masks serious or even terminal problems.”43 This concern could certainly be applied to Ben & Jerry’s situation. It seems that they are considering a partnership not only as a means of distribution, but also to build a strategy for them. Ben & Jerry’s needs to first consider what its strategy is, then decide on a partnership based on their objectives. There are at least two other main options that Ben & Jerry’s should consider: franchising and licensing. In the text International Marketing, Cateora and Graham state that the benefits of franchising include the ability to build a presence in foreign markets; the franchisee bears most of the costs and risks; and that the franchisor only has to recruit, train, and support franchisees, leaving them to run the day-to-day operations44. Of course, they also recognize that the primary problem with franchising is that it is difficult to maintain quality control.45 These benefits could be very advantageous to Ben & Jerry’s. Franchising scoop shops would not only allow them to build a brand awareness that being sold in convenience stores would not, but it also allows them to hand the costs, risks, and daily operations off to someone else without losing the valuable lessons that can come from making strategy. We could ensure the quality of the scoop shop through inspections, with incentives for those franchisees whose shops maintained a high level of quality. Franchising would also enable Ben & Jerry’s to maintain small, intimate shops Sellers, Simac, Straub, & Yu Ben & Jerry’s and Japan 15 that are befitting to the Japanese lifestyles. By franchising, Ben & Jerry’s could gain brand awareness that could then be used to expand into convenience stores such as 7Eleven. They would then have more leverage in the bargaining process, and not have to choose from unacceptable offers. Thompson & Strickland explained the benefits and drawbacks to licensing, or giving someone else the production rights to the product.46 The benefits are that it allows Ben & Jerry’s to forego the risk and costs of entering the foreign market on their own, but it still allows them to collect royalties off of the sale of the products. Of course, in giving someone else control over the operations, Ben & Jerry’s loses control over the quality of the product and any attempts at meeting social objectives in Japan. Recommendations So, Perry Odak and his staff were faced with the tiring decision of what option to follow. It seemed that no matter what they decided, it would be difficult to employ a social mission. They could accept 7-Eleven’s offer, and have instant access to the large market, but at the price of decreased bargaining power. Or, they could partner with Yamada. He could provide some great expertise, but at the cost of total control. Both of these strategies entail the risks inherent in exporting, which could be harsh if the Japanese economy did not turn around. Although these options do have their benefits, we recommend that Odak delay making his decision and consider his other options. The costs and risks inherent with the two options presented to him combined with the costs and risks of not having a coherent strategy in place before pursuing an international expansion are too high, and offset any benefits that may be received. Franchising and licensing have not even been fully Sellers, Simac, Straub, & Yu Ben & Jerry’s and Japan 16 considered by Odak; franchising especially presents a great option because of its combination of low risks and costs with little loss of control, while still providing Ben & Jerry’s with a learning opportunity that can lead into future expansion and growth. Ben & Jerry’s actually did enter the Japanese market with 7-Eleven in 1999, but with no mention of a social mission. However, they did not stick around long. Ben & Jerry’s was forced out of Japan because they could not build up the brand awareness to compete with the market leader, Haagen-Dazs. Current Status There is no doubt that Ben and Jerry’s has successfully built up its image with their chunky ingredients and funky names. By way of those dazzling characteristics, they have gained a competitive market share in the ice cream industry. However, the anticorporate style that Ben & Jerry’s found success with in the beginning is no longer feasible for what their company has grown into. In 2001 the company produced sales of about 300 million.47 In April 2000, the European consumer products giant, Unilever, bought out the business from Ben and Jerry’s for about $355 million. In December of the same year, Ben Cohen and Jerry Greenfield threatened to leave their position as the special advisers when the Anglo-Dutch group selected a new chief executive for the company.48 Although Ben & Jerry’s was bought out by Unilever, their mission of caring capitalism has not been changed. They continue to dedicate 7.5 per cent of pretax profits to good causes such as, AIDS and homelessness.49 A special Employee Community Fund has been set up to provide grants to Vermont nonprofits. Also they donate factory seconds to community organizations to sell to raise money for local libraries, recreation Sellers, Simac, Straub, & Yu Ben & Jerry’s and Japan 17 centers, and other facilities.50 Recently Ben & Jerry’s teamed with the Dave Matthews Band and many other environmental groups in a program to support an end to global warming and to promote a new flavor, One Sweet Whirled. This program meets Ben & Jerry’s mission of caring capitalism as well as creatively targeting a group predominately between the ages of eighteen and twenty four year-olds. These are the people who listen to the Dave Mathew’s Band and also who are the highest proportion of the superpremium ice cream market.51 Ben & Jerry’s has been expected to be expanding its international sales since its acquisition by Unilever two years ago. The company has expanded its business in the United Kingdom, France, Benulux, Canada, and Israel. Ben & Jerry’s has planned for a $15 million expansion of its St. Albans, VT manufacturing facility. The expansion is part of an overall restructuring that is intended to streamline production and distribution so that the company can be more competitive in the global marketplace.52 There are also future plans of opening 100 ice cream parlors throughout Spain over the next four years. This venture will be achieved mainly through franchises. Again Haagen-Dazs will be its main competitor.53 Sellers, Simac, Straub, & Yu Ben & Jerry’s and Japan 18 Appendix I Source: Bank of Japan, 2003 Sellers, Simac, Straub, & Yu Ben & Jerry’s and Japan 19 Appendix II Please answer the following questions: Have you ever owned, operated or managed a business? yes no Do you have food service or retail experience? yes no Do you have strong management, marketing and communication skills and experience? yes no Are you actively involved in your community? yes no Is your net worth above $200,000 (exclusive of your primary residence)? yes no Is your liquid net worth above $80,000? yes no Do you have excellent credit history? yes no Are you willing to devote your full time efforts to a Ben & Jerry's Franchise? yes no Do you have the desire and ability to manage the complexities of developing a new business? yes no Assuming your review of Ben & Jerry's is positive, are you prepared to make a decision about the Franchise within 60 or 90 days? yes no http://www.benjerry.com/scoop/franchise/prequal.html?market_status=closed Sellers, Simac, Straub, & Yu Ben & Jerry’s and Japan 20 Works Cited Bank of Japan. “Statistical handbook of Japan 2002.” Statistics Bureau & Statistics Center: Ministry of Public Management, Home Affairs, Posts, and Telecommunications. Online. Available: http://www.stat.go.jp/english/data/handbook/c03cont.htm. 28 March 2003. Bartlett, C. & Ghoshal, S. Transnational management: Text, cases, and readings in crossborder management, 3rd ed. McGraw-Hill Higher Education, 2000. “Ben & Jerry’s announces production changes.” Ice Cream Reporter. 20 May 2002. Vol 15 No 5 Pg 2. “Ben & Jerry’s teams with Dave Matthews Band for One Sweet Whirled.” Ice Cream Reporter. 20 February 2002. Vol 15 No 2 Pg 2. “Ben & Jerry’s to open 100 ice cream parlours within four year.” Financial Times. 12 April 2002. Cateora, P. & Graham, J. International marketing, 10th ed. Irwin McGraw-Hill, 1999. Doran, J. “Unilever chief gets taste for expansion at Ben & Jerry’s.” The London Times. 4 August 2001. Hagen, J. “Ben & Jerry’s – Japan.” 1999. Printed in: Thompson, A. & Strickland, A. Strategic management: Concepts and cases, 12th ed. McGraw-Hill Higher Education, 2001. Johnson, Cecil. "50 businesses that stand out, for better or for worse." Business and Financial News. 29 June 2001. “Mission Statement.” Ben & Jerry’s. Online. Available: http://www.benjerry.com/mission.html. 28 March 2003. Sellers, Simac, Straub, & Yu Ben & Jerry’s and Japan 21 “Nonconsolidated financial highlights.” Seven-Eleven Japan Co., Ltd. Online: Available: http://www.seveneleven.com/. 28 March 2003. Thompson, A. & Strickland, A. Strategic management: Concepts and cases, 12th ed. McGraw-Hill Higher Education, 2001. 1 Hagen, 1999. Ibid. 3 Ibid. 4 Ibid. 5 Ibid. 6 Ibid. 7 Ibid. 8 Ibid. 9 Ibid. 10 Ibid. 11 Bank of Japan, 2003. 12 Ibid. 13 Hagen, 1999. 14 Ibid. 15 Ibid. 16 Ibid. 17 Ibid. 18 Ibid. 19 Ibid. 20 Ibid. 21 Ibid. 22 Ibid. 23 Ibid. 24 Cateora & Graham, 1999. 25 Hagen, 1999. 26 Ibid. 27 Ibid. 28 Ibid. 29 7-Eleven, 2003. 30 Hagen, 1999. 31 7-Eleven, 2003. 32 Hagen, 1999. 33 Ibid. 34 Ibid. 35 Ibid. 36 Ibid. 37 Ibid. 38 Ibid. 39 Ibid. 40 Ibid. 41 Ibid. 42 Ibid. 43 2000, p. 416. 44 1999. 2 Sellers, Simac, Straub, & Yu Ben & Jerry’s and Japan 22 45 Cateora & Graham, 1999. 2001. 47 Doran, 2001. 48 Ibid. 49 Johnson, 2001. 50 Ibid. 51 Ben & Jerry’s teams, 2002. 52 Ben & Jerry’s announces, 2002. 53 Ben & Jerry’s opens, 2002. 46 Sellers, Simac, Straub, & Yu