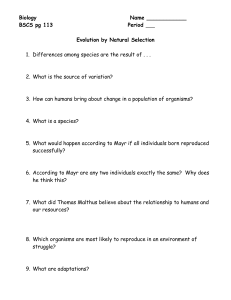

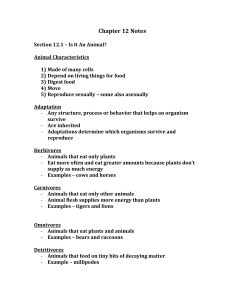

adaptations working group

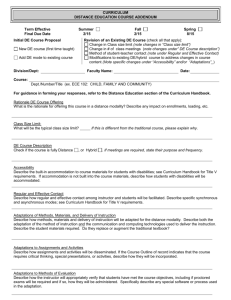

advertisement