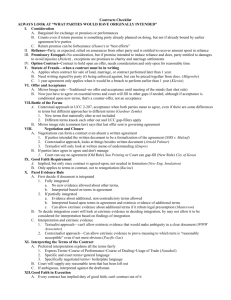

Contracts Outline – Greenfield

advertisement