Essay on “Prevailing Political And Cultural Convention”

advertisement

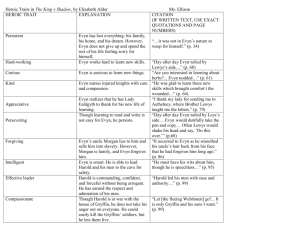

Mavarine Du-Marie Personal ID: M2515473 The Open University Question Compare Byron's Childe Harold Canto III and two other texts from the course in terms of their attitude to prevailing political and/or cultural convention. Number of words: 1,978 Page 1 of 7 In appraising the literature text of Childe Harold Canto III with two other texts; Olney Hymns Three and Dr Faust in terms of their attitude to the prevailing cultural convention, during the eighteenth century, it becomes clear that Romantic values took precedence over that of the Enlightenment principles. As Romanticism was a counter-culture to the Enlightenment; it was opposite to the accepted outer senses, and the traditional male hero, to whom the 17th century Encyclopédie explained him to be the embodiment of Enlightenment ideals of steadfastness, intrepidness, valiance, and, the great man as having morals; who's behaviour exhibited noble motives.1 Whereas, the Romantic sentiment was an emotion which could express the inner feeling, and came to be represented as the 'Romantic male', that is, an anti-hero and a great man of vices whom was defined as "...a very indifferent character, [who] might have done more and expressed less..."2 by their behaviour in society; "....mad, bad and dangerous to know."3 Therefore culturally considered to be avant-garde, because the anti-hero was seen as someone who transgressed physically, without limits mentally and strived to know himself spiritually. However, historically, there was a pre-Romantic culture, which had given credibility to express ones feelings4 too, such as espoused by Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778) in his reflections: "....[a]lone for the rest of my life - since I find consolation, hope, and peace only in myself - I no longer ought nor want to concern myself with anything but me. It is in this state that I again take up the sequel to the severe and sincere examination I formerly called my Confessions. I consecrate my last days to studying myself and to preparing in advance the account I will give myself before long. Let me give myself up entirely to the sweetness of conversing with my soul, since that is the only thing men cannot take away from me...."5 Mavarine Du-Marie Personal ID: M2515473 The Open University in his Reveries of the Solitary Walker published posthumously in 1782. This precursor gave rise to the concept of the cult of sensibility as an aspect of European culture, in terms of both art and life, but specifically, in the literary genre of the anti-hero, by authors using the literary device of pathos; as a means of invoking the emotions of a reader of their texts, as exemplified by Rousseau in his romantic confessions6 by which it can be clearly identified as being a sentimental work, and solely, in a male narrator's voice. Therefore, the nature of the romantic anti-hero's individualism can also be read into the eighteenth century literature texts of three works; Childe Harold's Pilgrimage, Canto III, stanzas 8-16, by Lord Bryon (1788-1824),7 Faust Part Two, Faust's Last Speech, by Johann Wolfgang Goethe (1749-1832)8 and The Olney Hymns: Hymn 3, Uncertainty of Life by John Newton (1725-1807)9, as all have an emphasis on the anti-hero's life experience romantically being "....as a whole new state of mind[.]"10 Thus by comparing the drama of Harold's 'pilgrimage', the Olney Hymn Three narrator's voice about the 'uncertainties of life' and Faust's "...desperate yearning for some understanding of 'the force that binds all Nature's energies' (22)..."11 there's a comprehension in terms of the cultural thoughts, of a romantic male's character, as written by the authors, as having prevailed the conventions of society, at that time, in fiction. For by analysing the text of only Harold's own pilgrimage of Canto III written in stanzas eight to sixteen, there is the evidence of the 'setting out' to find or lose himself, and his importance is given in capital letters in the spelling of his name; the reader is impressed to remember this man Harold, for he is 'the' archetypal romantic anti-hero; who comes and goes as he pleases with indifference, because as bluntly stated regarding Harold's character, that he's: "...[S]ecure in guarded coldness, he had mix'd / Again in fancied safety with his kind, / And deem'd his spirit now so firmly fix'd / And sheath'd with an invulnerable mind, / That, if no joy, no sorrow lurk'd behind; / And he, as one, might midst the many stand / Unheeded, searching through the crowd to find..." in stanza ten, lines 82 to 88. Thereat Harold is at ease within the prevailing cultural Mavarine Du-Marie Personal ID: M2515473 The Open University conventions - even though not of them - that is, Harold is sought out by others in society as there's "...[F]it speculation! such as in strange land, / He found in wonder-works of God and Nature's hand...," stated in stanza ten which describes Harold's physical being and later on in the prose metaphorically likens him to a 'wild-born falcon'12, as well as, the use of strong figurative language: "....Where rose the mountains, there to him were friends; / Where roll'd the ocean, thereon was his home; / Where a blue sky, and glowing clime, extends, / He had the passion and the power to roam; / The desart, forest, cavern, breaker's foam, / Were unto him companionship; they spake...." of Harold's affinity with nature, which is thrust at the reader in stanza thirteen, in other words, he was a different kind of man who had an unknown quality with regard to his persons' which set him apart from others. Therefore it does seem appropriate that Harold is the "...central character in this [play because he] lacks the traditional heroic virtues..."13 in this particular 'framed-narrative' of Canto III as to be the anti-heroic figure. However, any man in a conventional society would strive to differentiate himself because "...in Man's dwellings he became a thing, / Restless and worn, and stern and wearisome..." as proclaimed in lines 127 to 128, that every-day existence mattered little and offered his self-esteem nothing in return that Harold left the scene abruptly as he had entered for "...on with the giddy circle, chasing time, /Yet with a nobler aim than in his youth's fond prime..." in lines 98 to 99, which prevails upon the senses of the listener the detached manner of the anti-hero's attitude in a conventional society although HAROLD's presence is still there every-time the prose of Canto III is read. Therefore, Harold is a 'protagonist' within Canto III simply because he prevails to be his own person; an individual among other men, yet silently supportive of another man's voyage - as to be there physically on board but not mentally - which is so anti-heroic with a certain arrogance for: "....he knew himself the most unfit / Of men to herd with Man; with whom held / Little in common; untaught to submit / His thoughts to others, though his soul was quell'd / In youth by his own thoughts; still uncompell'd, / He would not yield dominion Mavarine Du-Marie Personal ID: M2515473 The Open University of his mind / To spirits against who his own rebell'd; / Proud though in desolation; which could find / A life within itself, to breathe without mankind...." said in stanza twelve, which could have evoked a feeling of being a kindred spirit when read, because Harold was also a great man of vices as "...the very knowledge that he lived in vain...." written stanza sixteen, meaning Harold had been a man who lived and embodied the spirit of his time, therefore was seen as a thoroughly 'modern man of Europe' 14, which was so profound that another man would have felt a pang of familiarity too with regards to flights "...that keeps us from yon heaven which woos us to its brink..." as stated in line 126 regarding 'human frailties' as mentioned in stanza fourteen. By comparison, in a similar vein to this is Olney Hymns Three: Uncertainty of life, where the narrator says "I am standing on the brink..." in verse three, thus confirming to the reader how frail life really is, but, goes on to state "...[I]f from guilt and sin set free, / by the knowledge of thy grace; / Welcome, then, the call will be to depart and see thy face..." in verse four. This expression in verse one, of an intimate thought, of a man looking inwards to his spiritual self and left 'wanting', as by the usage in the wording of the verse to convey to the reader those actual feelings of 'time elapsing' and not 'conversing with the soul' as Jean-Jacques Rousseau had mentioned earlier, for it says: "...When the former year begun: / Some, but who GOD only knows, / Who are here assembled now; / Ere the present year shall close, To the stroke of death must bow..." in verse two, was to understand that an anti-hero would've been acutely aware of his mortality and would engage in peregrination; exploring outwardly other worlds in an unknown adventure15 but internalising each experience as to sublimate the senses to become closer in fully knowing of himself before death occurs to his physical body. Compared to these attitudes of sublime thoughts, in a text from Dr Faust, its evident that he has no qualms with regard to cultural conventions being overturned for the sake of understanding his own limits, although he did start out with Enlightenment principles in seeking Knowledge, as he declared: Mavarine Du-Marie Personal ID: M2515473 The Open University "...Here I am, then. Philosophy behind me, / Law and Medicine too, / and - to my cost - Theology... all studied, grimly sweated through; / and here I sit, as big a fool as when I first attended school."16 However, the main concern of the text in Dr Faust was his transition to the Romantic ideals of living life to the full (even with the assistance of Mephistopheles): "...May rage and gnaw; and yet a / common will, / should it intrude, will act to close / the breach. Yes! to this vision I am wedded still,...." in his Faust last speech.17 Which was something borne out too in the text of Childe Harold when it states "...Who can contemplate Fame through clouds unfold / The star which rises o'ver her steep, nor climb?..." in stanza eleven. Although in Dr Faust his actions are more direct as to lose his soul through his own will, rather than being "...Which, though 'twere wild, - as on the plundered wreck..." in line 141 as the implied suggestion of what could occur regarding Harold’s fate.18 Comparatively, there is a strong similarity to all three chosen texts: the meeting of their deaths with such bold declarations of further deeds to be done still. This corresponds to Harold's being written out of the rest of the prose as: "...did yet inspire a cheer, which he forebore to check..." in the parting of ways at the end in the last line of 144, as too in Olney Hymn Three its written as: "...But the happiest year they know / Is their last, which leads them home..." in the last line of verse four and in Dr Faust he says "...This record of my earthly life shall last. / And in anticipation of such bliss / What moment could give me greater joy than this?" This all meant that the complete finishing of a romance wasn't a viable option to a true Romaunt19 who would have seen it rather as an opportunity for yet another journey for a Man to take, as "....they dealt with the 'far-away', where in time, place or culture (they characteristically summon up nostalgia, although typically at the same time they reflect critically from a modern perspective upon the escapist lure of romance..."20 and this prevailing Romantic attitude was at that time the accepted cultural convention in the eighteenth century. In summing up, the three texts of comparison between Childe Harold's Pilgrimage to Dr Mavarine Du-Marie Personal ID: M2515473 The Open University Faust and Olney Hymn number Three brings forth an understanding of the changing ideology from the period of Enlightenment to Romanticism, particularly towards the thoughts of males, during this time in society; as these specific texts were all written by men regarding Man and his sense of place in the world as a direct response to his own individualism21 in terms of their attitude to prevailing political and/or cultural convention. REFERENCES 1. pages 106-107, Unit 9: Napoleon and Painting, Block 2: The Napoleonic Phenomenon, A207 From Enlightenment to Romanticism c. 1780-1830, published by The Open University, ISBN: 0 7492 8596 6, copyright 2004. 2. page 202, Units 29-30: Bryon, Childe Harold III, Block 6: New Conceptions of Art and the Artist, A207 From Enlightenment to Romanticism c. 1780-1830, published by The Open University, ISBN: 0-74929600-3, copyright 2004. 3. page 198, Units 29-30: Bryon, Childe Harold III, Block 6: New Conceptions of Art and the Artist, A207 From Enlightenment to Romanticism c. 1780-1830, published by The Open University, ISBN: 0-74929600-3, copyright 2004. 4. pages 39-46, Unit 1, Course Introduction: Enlightenment and the Forces of Change, A207 From Enlightenment to Romanticism c. 1780-1830, published by The Open University, ISBN: 0-7492-8595-8, copyright 2004. 5. page 5-6, First Walk, The Reveries of the Solitary Walker, written by Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Translated by Charles E. Butterworth, published by Hackett Publishing Company, ISBN: 8-87220-162-7, copyright 1992. 6. page 228, Rousseau: Romantic confessions, Block 6: New Conceptions of Art and the Artist, A207 From Enlightenment to Romanticism c. 1780-1830, published by The Open University, ISBN: 0-7492-9600-3, copyright 2004. 7. pages 260-302, Lord Byron, Childe Harold's Pilgrimage, Canto the Third, 1816, Stanzas 8-16, From Enlightenment to Romanticism: Anthology II, edited by Carmen Lavin and Ian Donnachie, published by Manchester University Press, ISBN: 0-7190-6673-5, copyright 2004. 8. pages 247-248, Goethe, Faust Part Two: Faust's Last Speech, Part II Act V: The Great Forecourt of the Palace, Lines 11559-11586, From Enlightenment to Romanticism: Anthology II, edited by Carmen Lavin and Ian Donnachie, published by Manchester University Press, ISBN: 0-7190-6673-5, copyright 2004. 9. pages 248-249, Extracts from Book II, On Occasional Subjects, Hymn 3: Uncertainty of Life, The Olney Hymns in context, From Enlightenment to Romanticism: Anthology I, edited by Carmen Lavin and Ian Donnachie, published by Manchester University Press, ISBN: 0-7190-6673-5, copyright 2004. 10. page 251, Units 29-30: Bryon, Childe Harold III, Block 6: New Conceptions of Art and the Artist, A207 From Enlightenment to Romanticism c. 1780-1830, published by The Open University, ISBN: 07492-9600-3, copyright 2004. 11. page 104, Units 26-27: Goethe, Faust Part One, Block 6: New Conceptions of Art and the Artist, A207 Mavarine Du-Marie Personal ID: M2515473 The Open University From Enlightenment to Romanticism c. 1780-1830, published by The Open University, ISBN: 0-74929600-3, copyright 2004. 12. pages 265, Lord Byron, Childe Harold's Pilgrimage, Canto the Third, 1816, Stanzas 8-16, From Enlightenment to Romanticism: Anthology II, edited by Carmen Lavin and Ian Donnachie, published by Manchester University Press, ISBN: 0-7190-6673-5, copyright 2004. 13. page 39, The New Collins Dictionary & thesaurus in One Volume, managing editor William McLeod, published by HarperCollins Publishers, ISBN: 0-00-433186 9 copyright 1987. 14. page 240, Units 29-30: Bryon, Childe Harold III, Block 6: New Conceptions of Art and the Artist, A207 From Enlightenment to Romanticism c. 1780-1830, published by The Open University, ISBN: 07492-9600-3, copyright 2004. 15. page 242, Units 29-30: Bryon, Childe Harold III, Block 6: New Conceptions of Art and the Artist, A207 From Enlightenment to Romanticism c. 1780-1830, published by The Open University, ISBN: 07492-9600-3, copyright 2004. 16. page 39, Act One: Night - Faust's study, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe: Faust - A Tragedy: Parts One and Two, translated in a performing version by Robert David MacDonald, published by Oberon Books, London: Absolute Classic, ISBN: 1-870259-11-4, copyright 1988. 17. page 247, Goethe, Faust Part Two: Faust's Last Speech, Part II Act V: The Great Forecourt of the Palace, Lines 11559-11586, From Enlightenment to Romanticism: Anthology II, edited by Carmen Lavin and Ian Donnachie, published by Manchester University Press, ISBN: 0-7190-6673-5, copyright 2004. 18. pages 120-121, Course conclusion, Block 7: An overview of Romanticism A207 From Enlightenment to Romanticism c. 1780-1830, published by The Open University, ISBN:0 7432 9601 1 copyright 2004. 19. page 238, Units 29-30: Bryon, Childe Harold III, Block 6: New Conceptions of Art and the Artist, A207 From Enlightenment to Romanticism c. 1780-1830, published by The Open University, ISBN: 07492-9600-3, copyright 2004. 20. page 236, Units 29-30: Bryon, Childe Harold III, Block 6: New Conceptions of Art and the Artist, A207 From Enlightenment to Romanticism c. 1780-1830, published by The Open University, ISBN: 07492-9600-3, copyright 2004. 21. pages 123-126, Course conclusion, Block 7: An overview of Romanticism A207 From Enlightenment to Romanticism c. 1780-1830, published by The Open University, ISBN:0 7432 9601 1 copyright 2004.