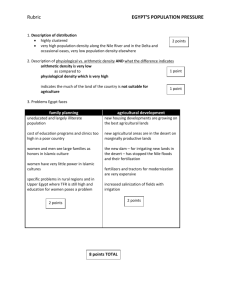

Agricultural Resources, Agricultural Production and Settlement

advertisement