Title: Educational Impact of a school breakfast program in rural Peru

advertisement

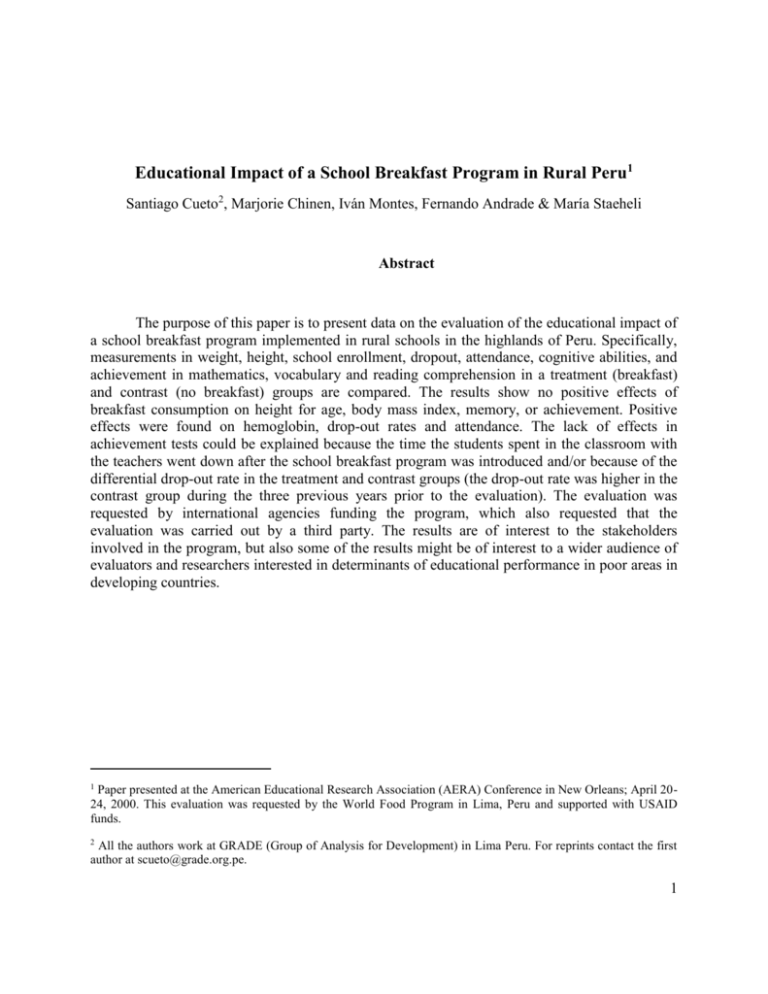

Educational Impact of a School Breakfast Program in Rural Peru1 Santiago Cueto2, Marjorie Chinen, Iván Montes, Fernando Andrade & María Staeheli Abstract The purpose of this paper is to present data on the evaluation of the educational impact of a school breakfast program implemented in rural schools in the highlands of Peru. Specifically, measurements in weight, height, school enrollment, dropout, attendance, cognitive abilities, and achievement in mathematics, vocabulary and reading comprehension in a treatment (breakfast) and contrast (no breakfast) groups are compared. The results show no positive effects of breakfast consumption on height for age, body mass index, memory, or achievement. Positive effects were found on hemoglobin, drop-out rates and attendance. The lack of effects in achievement tests could be explained because the time the students spent in the classroom with the teachers went down after the school breakfast program was introduced and/or because of the differential drop-out rate in the treatment and contrast groups (the drop-out rate was higher in the contrast group during the three previous years prior to the evaluation). The evaluation was requested by international agencies funding the program, which also requested that the evaluation was carried out by a third party. The results are of interest to the stakeholders involved in the program, but also some of the results might be of interest to a wider audience of evaluators and researchers interested in determinants of educational performance in poor areas in developing countries. 1 Paper presented at the American Educational Research Association (AERA) Conference in New Orleans; April 2024, 2000. This evaluation was requested by the World Food Program in Lima, Peru and supported with USAID funds. 2 All the authors work at GRADE (Group of Analysis for Development) in Lima Peru. For reprints contact the first author at scueto@grade.org.pe. 1 Introduction School breakfast programs are frequently considered an effective intervention to improve educational efficiency in poor schools in developing countries (Lockheed & Verspoor, 1991). School breakfast programs are targeted to improve the "teachability" of students, especially those that are undernourished (Levinger, 1994), by bettering the nutritional and health status of the children. The hypothesis is that children in poor schools often times do not achieve in school as expected because of malnutrition and or sickness (Pollitt, 1990). School breakfast programs are usually targeted at improving the nutritional status of these children and, in the long run, their health status. But improving nutritional and health status is only one of the routes in which school breakfast programs could help children achieve better in school. A second route is related to short-term nutritional effects. In undernourished populations, providing a school breakfast program is expected to increase temporarily cognitive capabilities, which in turn would help students learn more while at school. A few laboratory studies have found a negative impact of short-term fasting on cognitive abilities, especially short-term memory and attention, among undernourished children (e.g. Simeon and Grantham-McGregor, 1989; Cueto, Jacoby, Pollitt, 1998). The experimental design of these studies included overnight fasting in a controlled environment for the control group, versus consumption of breakfast in the experimental group. The explanation for the result is not clear, but it seems likely that breakfast consumption increases glucose level, which in turn has a positive short-term effect on cognitive abilities (Korol & Gold, 1998). A final route by which a school breakfast program could improve educational achievement is not nutritional, but economic. Parents in impoverished environments could send their children to school daily, and not let them drop out, because the breakfast at school helps the household economy. There are a few studies that have found a positive association between providing breakfast at school and daily attendance (Grantham-McGregor, Chang & Walker, 1998a), but no studies have been identified that relating breakfast consumption and dropping out of school. The first and third routes could be related, because, as mentioned before, children that improve their nutritional status in the long run get sick less often and may attend school more frequently. For a school breakfast program to have an impact on learning, there should be an educational environment at school that favors learning. In other words it is not sufficient that the child is well nourished, healthy and at school for learning to occur. For instance, in an evaluation of a school breakfast program in Jamaica, Grantham-McGregor, Chang and Walker (1998b) found positive effects only in schools that worked "better". In this study the issue of school quality is approached with a proxy for time on task. This because time on task is very low in rural schools in Peru (e.g. Cueto, Jacoby & Pollitt, 1997, the same study shows a positive association of time on task and school achievement). Figure 1 summarizes the theoretical framework adopted and the variables tested in this study for each route. 2 Figure 1: Theoretical framework Route 1: Breakfast improves nutritional condition Hemoglobin Anthropometry Route 2: Breakfast improves cognitive awareness - Memory test - Coding test Route 3: Breakfast improves school attendance Achievement tests: Vocabulary Reading comprehension Arithmetic - Attendance rate - School dropout rate - Enrollment rate Note: The effects on achievement are moderated by school quality The hypothesis for the study is that children who consumed the school breakfast will show higher levels of hemoglobin, higher anthropometric levels (height for age and body mass index), higher scores in cognitive and achievement tests, higher rates of attendance and enrollment and lower drop-out rates than children living and studying in similar contexts who do not consume the school breakfast. The School Breakfast Program The school breakfast program evaluated is one of several carried out by the Peruvian government. In this case the program is run jointly with an international agency in three of the poorest departments (INEI, 1994) of Peru: Ayacucho, Apurímac and Huancavelica, all located in the highlands. One of the objectives of the program is to “eliminate hunger and reduce anemia trough a nutritional supplement to children in preschool and primary school, so that the students’ ability to learn are improved”. The school breakfast program consists of cup of a milk-like beverage (with no lactose in it) in three flavors and 6 small biscuits. The nutritional composition of the breakfast is presented in Table 1. 3 Table 1. Nutritional Composition of the School Breakfast Daily Ration - Iron - Calcium - Phosphorus - Zinc - Vitamin A - Folic Acid - Vitamin B12 - Tiamin - Riboflavin - Niacin - Vitamin B6 - Vitamin C - Iodine Beverage 7.2 mg 480 mg 480 mg 6 mg 240 ug 60 ug 0.84 ug 0.60 mg 0.72 mg 7.8 mg 0.84 mg 27 mg 72 ug Biscuits 6 mg One ration of the breakfast is designed to provide energy (600 Kcal), protein (22.5 grams) and fat (20 grams). Also it is designed to provide 60% of the daily requirements of several vitamins and minerals needed by children (see Table 1), and 100% of the daily requirements of iron. The relatively higher iron supplementation is based on several studies that show the negative relationship between iron deficiency anemia and intellectual development and school achievement (Pollitt, 1990). The breakfast is centrally produced so as to maintain nutritional quality. The biscuits are ready to eat and the beverage is in powder, so it has to be diluted in boiling water before serving. At each school parents and teachers are expected to form committees to receive and maintain the breakfast supplies and serve breakfast Monday through Friday during the school year (beginning of April through early-December). One interesting fact is that the school breakfast program is mostly consumed at mid-morning. The reason is that most children have to walk long distances to get from home to school, often times more than 30 minutes each way up or down steep mountains, so parents will not let their children go to school with empty stomachs3. Since most students are not hungry when school classes start (around 8:30 or 9:00 a.m.), and as a general rule parents are not available to prepare the beverage before 9:00 a.m., the school breakfast is served during recess time (between 10:00 and 11:00 a.m.) 3 Another reason for this is that classes are often times cancelled without previous notification to the parents. When this happens children get to school to find it closed, and usually do not get the school breakfast. 4 Methods Design The design included a breakfast (treatment group) and no breakfast (contrast group) in two neighbor departments (Apurimac and Cusco) in the highlands of Peru. The evaluation was designed after the school breakfast program was started, so it was not possible to assign students or schools randomly and for some variables baseline measurements were not available (i.e. tests, monthly attendance, anthropometry and hemoglobin; enrollment and dropout and time on task). The treatment group was selected in only one of the provinces to facilitate logistics. This province was considered to be a “typical” province by program officers (from official statistics the province was either “poor” or “very poor” depending on the indicator; INEI, 1994). The contrast group was selected from provinces and schools carefully matched on altitude (around 3000 meters above sea level), bilingualism (Quechua and Spanish are spoken widely in this area), size and type of the school, poverty indexes of the districts where the schools were located, and family occupation (mostly peasants). Treatment and contrast groups were visited individually before deciding on their inclusion. The only reason the control group was not receiving the program was logistics, and actually the students from the control group started receiving a slightly different school breakfast program (also sponsored by the government) right after this evaluation was completed (1998). All breakfast schools were in their third year into the program. To test route 1, the anthropometry (height for age and body corporal index) and hemoglobin levels4 of children in the treatment and contrast groups were compared. To test route 2, the results of children in the treatment and contrast groups in tests of short-term memory and learning were compared. Since short-term effects were being explored, the tests were administered immediately after receiving breakfast at school (in the treatment group, consumption of breakfast was verified), or at the same time (around 11:00 a.m.) in the contrast group (were no school meals of any type were being served). To test route 3, the attendance rate for each month during 1998 in the treatment and contrast groups were compared; also the enrollment and drop-out rates in the treatment and contrast groups before and after the school breakfast program started were compared. Locations, Schools and Subjects The treatment group was located in the districts of Talavera, Pacucha and Kishuara in the department of Apurimac. The contrast group was located in the districts of Chinchaypucyo, Mollepata and Huanoquite in the department of Cusco. There are several indicators that show these provinces to be among the poorest in Peru. For instance, chronic malnutrition (height for age < -2 s.d. of the NCHS standards) was found in 66% of first-grade children in the contrast group and 69% of the children in same grade in the treatment group (Ministerio de Educación, 1993). 4 The comparison of the hemoglobin levels between a treatment and comparison group were made based on a partially different sample. See the appendix for details and results. 5 There were 11 schools in the treatment group. Of these, 5 were full grade schools, where students from different grades were kept in classrooms separate, and 6 were multiple grade schools, where students of two or more grades were kept in the same classroom. The latter are usually the smaller and poorer schools, and one teacher has to accommodate for the diverse needs of the students without receiving special training or educational materials for this. In the contrast group there were 9 schools, 3 full grade and 6 multiple grade schools. The sample consisted of 350 fourth-grade students. At fourth grade students are expected to master basic skills, some of which were included in the achievement tests. Some demographic characteristics are presented in Table 2 (the comparison between the treatment and contrast groups was performed with a t-test). The data for the subjects in the treatment group were different in several variables from that for the subjects in the contrast group. In general there was less poverty and less bilingualism in the contrast group. One possible explanation was that the selection and matching of districts and schools was wrong, but this is unlikely since several indicators from the last Census were used (INEI, 1994), and these showed that schools and districts were very similar. The second possible explanation is that the school breakfast program has had an impact on school enrollment and/or dropout, causing the poorer, more bilingual students from the contrast group to drop out of school. This explanation has some support in data that is presented later. Table 2- Subjects characteristics in the Treatment and Contrast Groups Number of subjects Male (%) Female (%) Treatment Group Contrast Group 169 181 50.8 49.2 49.5 50.5 Children's Age (in years) (Standard deviation) 11.81 (1.76) 11.7 (1.92) Spanish proficiency a (Standard deviation) 2.02 (0.68) 2.52 ** (0.66) Mother's average years in school (Standard deviation) 1.37 (2.07) 3.22 ** (3.09) Average walking distance from house to school (in minutes) (Standard deviation) 30.19** (24.62) 17.24 (20.04) Family size (Standard deviation) 6.43 (1.78) 6.19 (1.97) Electricity b (Standard deviation) 0.119 (0.32) 0.388 ** (0.49) (*) Significant p<0.05 (**) Significant p<0.01 a 1=very poor / 2=medium / 3= high b 1=electricity at home/ 0=no electricity at home 6 Variables and Instruments Hemoglobin measurements were carried out at each school with the Hemocue ®, so as to provide immediate written results. Written parental consent for each child was gathered before taking a drop of blood from one finger for this measurement. The results were adjusted for altitude (using the tables in Zavaleta et al, 1998) and given immediately to one of the parents, with recommendations for an iron-rich diet or treatment if the results showed anemia. Local nurses were trained to carry out these procedures in a standardized way. Weight was determined with a bathroom scale, and height with a child height measuring board. The weight scales were calibrated every day before use with a 5 kg weight; the height board was calibrated once at the beginning of the data collection. Local nurses were standardized in the procedures. Using the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) tables included in the EPINUT program, an individual height for age z-score (indicator or chronic malnutrition) was calculated. The usual indicator of acute malnutrition (weight for height) could not be estimated for the majority of subjects, since the ages of many children went beyond the NCHS table values. Thus a substitute, the body mass index (BMI), was used (BMI was defined as kg/height in meters2). The correlation between body mass index and weight for height for the 115 subjects that had both values was r=0.93 (p<0.001). The cognitive instruments to assess short-term effects of breakfast consumption were a shortterm memory test (Yuste, 1998), and a group adaptation of the coding test from the WISC. Both did not require to write words for an answer, but to circle objects in a farm illustration that were not included in a previously shown illustration (memory test) and to fill one code for each number 1 through 9 (as shown on the top of the page, the codes were the same as those used in the WISC). Monthly attendance data for all students grades 1-6 were taken from teachers records. Since these were sometimes incomplete, all data was recorded and percentages calculated. Yearly enrolment and dropout were taken from records at the departmental office for grades 1-6. For dropout and enrollment only between 5 and 9 schools per group (depending on the variable) had data for all years. This is the data presented. Regarding achievement, it was decided not to use curriculum-based tests because it was found that curriculum coverage was uneven among schools. The three achievement tests administered evaluated basic skills that were covered in all schools. They were: Arithmetic (24 items asking students to perform additions, substractions, multiplications and divisions, with no text problems, only number and the symbols for the operations), vocabulary and reading comprehension (40 items for each, all written in Spanish). All tests were scored 1 point for a correct answer and 0 for a wrong answer or blank. Since the evaluation was carried out in rural, bilingual areas (Quechua and Spanish), where there is very little usage of standardized tests, the biggest challenge was to select and adapt instruments that were reliable and valid. Except for the memory test, all had been used previously in similar areas with good results (Jacoby, Cueto & Pollitt, 1999). Still, several pilot administrations were carried out, until reasonable internal coefficients were found (i.e. above 7 0.70). When written items were necessary (i.e. for vocabulary and reading comprehension) the tests were in Spanish. This is because many of the children in the sample speak Quechua as their mother’s tongue, but do not read or write it. They are taught at school to read and write in Spanish only, and all textbooks and educational materials are in Spanish5. The instructions for the tests were given in both Spanish and Quechua6. Time on task was defined as the average time the students spent in the classroom with the teacher inside the classroom daily. This time was taken for each school on different weekdays (between 2 and 5 observations per school) by trained field workers. Other covariates were defined based on previous studies on impact evaluations of school breakfast programs. These were: children’s age, gender and ability in Spanish (as defined by the teacher on a scale from 1 to 3, the higher indicating a good command and the lower a poor command of Spanish), mother’s educational level (in school grades completed), presence of light at home, type of school (full grade or multiple grade), average walking time from home to school and back (recorded in minutes by the field workers), and the years of experience of the fourth grade teacher. Children and family data were obtained from one or both parents at home. The interviews were carried out mostly in Quechua by the field workers. Procedures Local field workers were hired to visit each school at least once a week (rotating the day and not announcing the visit previously to the principal) to verify that the breakfast was being served regularly and consumed by the children. The field workers also checked for student attendance. Only children that were reported to consume at least half of the breakfast daily (according to their teachers) were used in the analysis of the cognitive and achievement tests and hemoglobin measurements (this last condition for the experimental group only). This was to check that the treatment children were indeed participating in the program. Only 13 children were dropped from the sample because of the above criteria. Data was collected from August through November of 1998. Analysis Descriptive statistics were used to present longitudinal data on attendance, enrollment and dropout. To analyze the data from the tests, a Hierarchical Linear Model (HLM) was used (Bryk & Raudenbush, 1992), with two levels. To analyze the data from anthropometry and hemoglobin an analysis of covariance was performed. 5 There are bilingual schools in Peru, but they serve only around 10% of the bilingual population. No bilingual schools were included in the sample. 6 Local, bilingual teachers were specially hired and standardized in the procedures. 8 Results Regarding the first route (consumption of breakfast improves nutritional status), no differences were found between treatment and contrast groups in height for age z-scores (HAZ) or BMI (see Table 3). Table 3. Anthropometry indicators (adjusted means and standard errors) Contrast Group HAZ (Standard error) BMI (Standard error) -2.12 (0.07) n=157 17.35 (0.15) n=157 Treatment group -2.21 (0.08) n=147 17.42 (0.15) n=146 Analysis of covariance using the children's age, sex, educational level of the mother, average distance from home to school, family size and electricity as covariates. The cutoff score for chronic malnutrition is usually height for age <-2 s.d. of the NCHS tables. Thus the majority of children in the study suffer from chronic malnutrition. In other words these children need to better the quality of their diets, although height for age is not a specific indicator to show the nutritional deficiencies the children are suffering. From the results in body mass index and the field observations, it seems that hunger is not a problem in this area. The results for hemoglobin did show a difference between the treatment and contrast groups, but since the sample used for this was different from the one used in the rest of the study, the results are presented in the appendix. Regarding the second route, no short-term effects of breakfast consumption were found on the short-term memory or coding tests. The results for these tests are in the first two columns of Table 4. Also, no significant differences were observed between the treatment and contrast groups in any of the achievement tests administered (see last three rows of Table 4). Raw scores are presented. In the HLM analysis, group, school and teacher variables were introduced at level 2. The other, student, variables were introduced at level 1. 9 Table 4. HLM analysis for Tests (fixed variable coefficients and standard errors) Memory Coefficient - Intercept (Standard Error) - School typea (Standard Error) - Group b (Standard Error) - Years of experience of the teacher (Standard Error) - Gender c (Standard Error) - Child age (in years old) (Standard Error) - Spanish proficiency d (Standard Error) - Mothers education (in grades completed) (Standard Error) - Family size (Standard Error) - Average distance from house to school e (Standard Error) - Electricity f (Standard Error) Coding Coefficient Arithmetic Coefficient Vocabulary Coefficient Reading Comprehension Coefficient 37.81 ** 14.21 ** 17.62 ** 14.78 ** (0.48) (2.02) (0.59) (1.00) (0.84) -0.51 -5.04 -0.15 (1.05) (4.39) (1.29) (2.18) (1.84) 1.68 2.36 -0.54 -2.09 -0.52 (1.30) (5.38) (1.56) (2.64) (2.22) 8.59 ** -4.58 * -3.05 0.14 0.24 0.04 0.46 0.26 (0.12) (0.49) (0.14) (0.24) (0.20) 0.01 -1.86 0.38 -0.72 0.55 (0.47) (1.74) (0.45) (0.75) (0.61) 0.18 -0.35 (0.13) (0.21) -0.02 (0.13) 2.29 ** 1.98 ** (0.49) 5.85 ** 0.75 3.32 ** -0.63 ** (0.17) 2.85 ** (0.44) (1.64) (0.42) (0.70) (0.57) -0.05 -0.56 0.03 -0.04 -0.08 (0.10) (0.36) (0.09) (0.15) (0.12) 0.03 -0.13 -0.13 -0.30 -0.31 (0.13) (0.48) (0.12) (0.20) (0.17) -0.01 0.03 -0.02 -0.03 -0.02 (0.01) (0.04) (0.01) (0.02) (0.01) -0.53 1.07 0.56 (0.70) (1.16) (0.94) -1.17 (0.73) 5.49 * (2.71) (*) p < 0.05 (**) p<0.01 a 1=multiple grade schools / 0= full grade schools b 1=treatment group / 0=contrast group c 1=male / 0=female d 1=no proficiency / 2=little proficiency / 3= good proficiency e Distance computed in minutes f 1=electricity / 0=no electricity The third route referred to the improvement of school attendance and enrollment and reducing dropout. Figure 2 presents the data for school attendance during the 1998 school year (the results by grade were very similar, so Figure 2 includes grades 1-6 combined). The results show clearly better attendance for the treatment group (monthly averages between 90% and 95%, compared to monthly averages between 80% and 87% in the contrast group). 10 Figure 2. School Attendance Rates during the 1998 School Year 100 Percent 95 90 85 80 75 april may june Contrast group july august september october november Treatment group Also related to the third route is the data on school enrollment and dropout. In this case the data for 1995 was used as baseline (the breakfast program started in 1996). So the enrollment and dropout figures for 1995 were defined as 0%, and all variations in the next years were compared against the baseline (see Figure 3). There were no significant increments in enrollment once the program started, but dropout was significantly reduced in the treatment group during the following three years. Data are presented for grades 1-6 combined. Figure 3. Enrollment and dropout rates for the 1995-1998 school years Percentage variation (compared to 1995) 40 20 0 1995 1996 1997 1998 -20 -40 -60 -80 Enrollment Contrast group Dropout Contrast group Enrollment treatment group Dropout treatment group 11 Finally, Figure 4 presents data on the time the schools spend in the classroom with the teachers. In this case there is a baseline: on period 1 the treatment group was consuming the school breakfast, while the contrast group was not. In period 2 the contrast group started receiving the school breakfast while the treatment group continued receiving it. On average, in the contrast group the time in the classroom went from 237 (period 1) to 198 (period 2) minutes per day, the reduction explained by the extra time given to breakfast preparation and consumption at school during recess time (as explained before, recess is the time when breakfast is served at schools). The minutes per day for the treatment group went from 213 to 212 minutes during the same periods. Figure 4. Time spent in the Classroom with the Teachers per day Classroom time (minutes) Ide al time 270 240 237 213 210 212 198 180 Period 1 (August -October) CG mean Period 2 (November) TG mean Discussion The impact evaluation of the school breakfast reported here tested for the effects of breakfast consumption on several variables: nutritional status, attendance, enrollment, memory and achievement. Regarding the nutritional variables, no effects were found on height for age or body mass index. In spite of the program’s goals, acute malnutrition does not seem to be a problem in the areas where the program is implemented. Overall, children are not hungry. But the quality of the children’s diet at home seems to be poor, and this shows in the high prevalence of chronic malnutrition (height for age). The fact that no effects were found in this variable could be explained because the intervention was started too late in the children’s life (between 6 and 7 years of age). Better results were found for the treatment group in hemoglobin (see Appendix). This shows that the school breakfast would be indeed contributing to improve the nutritional status of the children. The importance of improving iron status comes from its effects on intellectual development and school achievement (Pollitt, 1990). No significant differences were found on the memory and coding tests between the contrast and 12 treatment groups. This is in contrast to previous studies that showed that nutritionally at-risk children with breakfast perform better on memory tests than similar children that went through a short-term fasting period (Cueto, Jacoby & Pollit, 1998). But this study and similar were performed under laboratory conditions. In the present evaluation the comparison was between children who had consumed breakfast at home (contrast group) and children who had consumed breakfast at home in addition to the school breakfast (treatment group). The effects of the school breakfast in contexts similar to those studied might not occur in the short-term. Differences favoring the treatment group were found in the monthly attendance rates for the 1998 school year. This result is in agreement with several previous studies and could be considered a well-establish research finding. Also, no differences between the groups were found in school enrollment, but significant differences were found in the evolution of dropout rates from 1996 to 1998. This is a result that has not been reported previously in the literature, and should be confirmed in a larger sample. The policy implications of this result would be great, given that the drop-out rates in rural areas of Peru are high (on average the rural population 15 years of age or older in rural areas has completed only 6 years of education; Ministerio de Educación, 2000). Regarding the quality of the schools, the time the students spend daily in the classroom level is well below the official schedule (four and a half hours). Furthermore, complete school days are often cancelled for a variety of reasons: teacher meetings, parent meetings, teacher is sick and no substitute is available, teacher has to go to the capital of the province to cash a check, etc. The number of minutes spent in the classroom was lower for the treatment group, and went down in the contrast group once the school program started. No compensation time at the beginning or end of the day was accommodated. No differences were found in achievement between the treatment and contrast groups. The results could be explained by a lack of educational effects of the program, or one of two alternative explanations. The first is that the reported reduction in drop-out rates in the treatment group over a period of three years, would have kept the poorer, Quechua speaking children in the treatment group, while their equivalents in the contrast group would have dropped out. This would explain why the sample in the treatment group was poorer and more bilingual than the contrast group, even though previous socioeconomic indicators for the districts and schools were very similar. The poorer children in the treatment group would have brought down the means in the achievement tests. The covariates included in the analysis might not have corrected for the differences between the groups. A second explanation, that could complement the “drop out” explanation is that the school quality has been lower in the treatment groups since the implementation of the school breakfast program. The time spent in the classroom data would be an indicator of this, since it is obvious that if the students are not in the classroom they will not learn academic subjects. In the future, more school variables should be collected to get more complete measures of school quality. In the discussion of the implications of the results it is important to consider the limitations of the design. The data that have no baseline (anthropometry, hemoglobin, monthly attendance and all the tests) has less internal validity than the data that have a baseline (enrollment, drop-out and 13 time spent in the classroom). Based only on the latter results, it seems that the program has contributed to reduce drop out rates in rural areas of Peru, a major accomplishment in itself, but it also has had a negative side effect: it reduced the time the students spend in the classroom. Thus it seems that the program has a great potential to improve the educational levels of the rural population, but at the same time needs more and/or better monitoring so that the breakfast program does not decrease learning time for the students. 14 References Bryk, A. & Raudenbush , S. (1992). Hierarchical Linear Models. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications. Chandler, A., Walker, S., Connolly, K. & Grantham-McGregor, S. (1995). School breakfast improves verbal fluency in undernourished Jamaican children, Journal of Nutrition, 125, 894-900. Cueto, S., Jacoby, E., Pollitt, E. (1997), Time on task and educational activities in rural schools in Peru, Revista Latinoamericana de Estudios Educativos, XXVII(3), 105-120. Cueto, S., Jacoby, E., Pollitt, E. (1998). Breakfast prevents delays of attention and memory functions among nutritionally at-risk boys, Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 19(2), 219-234 Cueto, S., Montes, I., Chinen, M., Andrade, F. & Staeheli, M. (1999). Final Report on the Impact Evaluation of the School Breakfast Program. Grantham-McGregor, S., Chang, S., Walker, S. (1998a). School feeding studies in Jamaica. In PAHO: Nutrition, health and child development (pp. 104-118). Washington D.C.: Author. Grantham-McGregor, S., Chang, S., Walker, S. (1998b). Evaluation of school feeding programs: Some jamaican examples. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 67S(4S), 785S-789S. INEI (1994). Mapa de Necesidades Básicas Insatisfechas de los Hogares a Nivel Distrital. Lima: Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática. Korol, D. & Gold, P. (1998). Glucose, memory and aging. Suppplement to the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 67(4S), 772S-778S. Levinger, B. (1994). La nutricion, la salud y la educacion para todos (Nutrition, Health and Education for All). Boston: Education Development Center & UNDP. 15 Lockheed, M. & Verspoor, A. (1991) Improving primary education in developing countries. Washington D.C.: The World Bank & Oxford Press. Jacoby, E., Cueto, S., Pollitt, E. (1999). Determinants of school performance among Quechua children in the Peruvian Andes, International Review of Education, 45(1), 27-43. Ministerio de Educación (1993). Censo de Talla en Escolares. Lima: Author. Ministerio de Educación (2000). Education for All Assessment. Lima: Author. Pollitt, E. (1990). Malnutrition and Infection in the Classroom. Paris: UNESCO. Pollitt, E., Jacoby, E. & Cueto, S. (1996). Desayuno Escolar y Rendimiento. Lima: Apoyo. Simeon, D., Grantham-McGregor, S. (1989). Effects of missing breakfast on the cognitive functions of school children of differing nutritional status. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 49, 646-653. Yuste, C. (1998). Test de memoria. Madrid: TEA Ediciones. Zavaleta, N., Respicio, G., garcía, T., Echeandía, M. & Cueto, S. (1998). Anemia y Deficiencia de Hierro en Adolescentes Escolares en Lima, Perú. Causas, Consecuencias y Prevención. Lima: Instituto de Investigación Nutricional. 16 Appendix. Hemoglobin levels in Treatment and Contrast Groups Although the original study design called for a comparison of hemoglobin levels of the treatment and comparison groups, this could not be carried out. The reason was that, without previous notification to the researchers, the contrast group was assigned a school breakfast similar in nutritional composition to the one described before. The consumption of this breakfast could have affected the hemoglobin levels of the students. Thus a new contrast group had to be found in the same areas where the original contrast group existed (they were to be provided the school breakfast shortly after the collection of hemoglobin for this study). The treatment group was the same. The new contrast group, for comparison of hemoglobin levels, only, consisted of 101 children (47 male and 54 female) of 7 schools. Some demographic indicators collected show that this new contrast group is similar to the one described in the study (i.e. average age: 11.3 years; mother education in years completed: 4.31; HAZ: -2.09; BMI: 17.5). Figure 5 presents the data for hemoglobin levels in the treatment and comparison groups. Since many women have started their adolescence, and this is an age of increased risk for anemia, the results are presented separate for males and females. Figure 5. Hemoglobin levels for treatment and contrast group by gender. 1 2 .5 Adjust ed M ean for Hb (g/dl) 1 2 .2 1 2 .0 1 1 .7 1 1 .5 1 1 .2 1 0 .9 1 1 .0 1 0 .5 1 0 .0 F e m a le F e m a le M a le M a le C o n t r a st gr o up T r e a t m e n t gr o up C o n t r a st gr o up T r e a t m e n t gr o up A n a l ys i s o f c o va r i a n c e u s i n g th e c h i l d r e n 's a g e a n d e d u c a ti o n a l l e ve l o f th e m o th e r a s c o va r i a te s . p < 0 .0 5 fo r b o th c o m p a r i s o n s b e tw e e n tr e a tm e n t a n d c o m p a r i s o n g r o u p s . The treatment group had higher levels of hemoglobin. It is important to note that hemoglobin < 12.0 g/dL is the usual cut-off score for anemia. Most children in the contrast group were anemic, versus a minority in the treatment group (most of them close to the cut-off score). Hemoglobin is the most important indicator of iron status, and iron deficiency anemia is widely considered to be associated with school performance (Pollitt, 1990). The school breakfast program evaluated provided with 100% of the daily requirements of iron of the children, so this result was expected and is an indication that the program is achieving it long-term nutritional objectives. 17