Organizational adoption and diffusion of electronic meeting systems

advertisement

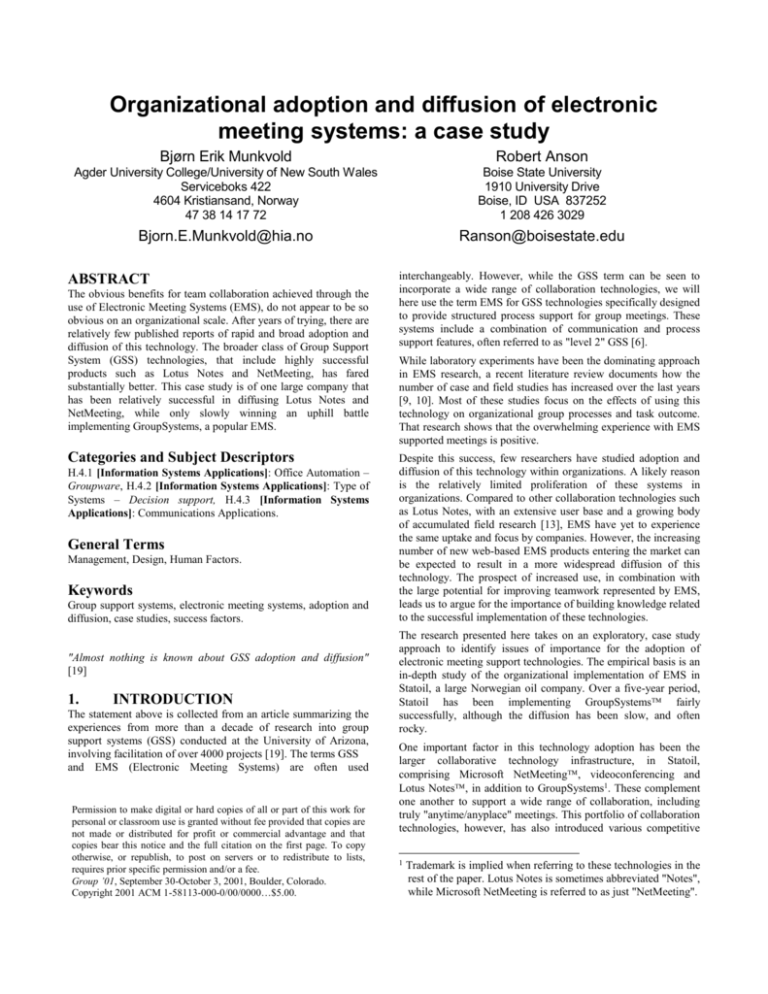

Organizational adoption and diffusion of electronic meeting systems: a case study Bjørn Erik Munkvold Robert Anson Agder University College/University of New South Wales Serviceboks 422 4604 Kristiansand, Norway 47 38 14 17 72 Boise State University 1910 University Drive Boise, ID USA 837252 1 208 426 3029 Bjorn.E.Munkvold@hia.no Ranson@boisestate.edu ABSTRACT The obvious benefits for team collaboration achieved through the use of Electronic Meeting Systems (EMS), do not appear to be so obvious on an organizational scale. After years of trying, there are relatively few published reports of rapid and broad adoption and diffusion of this technology. The broader class of Group Support System (GSS) technologies, that include highly successful products such as Lotus Notes and NetMeeting, has fared substantially better. This case study is of one large company that has been relatively successful in diffusing Lotus Notes and NetMeeting, while only slowly winning an uphill battle implementing GroupSystems, a popular EMS. Categories and Subject Descriptors H.4.1 [Information Systems Applications]: Office Automation – Groupware, H.4.2 [Information Systems Applications]: Type of Systems – Decision support, H.4.3 [Information Systems Applications]: Communications Applications. General Terms Management, Design, Human Factors. Keywords Group support systems, electronic meeting systems, adoption and diffusion, case studies, success factors. "Almost nothing is known about GSS adoption and diffusion" [19] 1. INTRODUCTION The statement above is collected from an article summarizing the experiences from more than a decade of research into group support systems (GSS) conducted at the University of Arizona, involving facilitation of over 4000 projects [19]. The terms GSS and EMS (Electronic Meeting Systems) are often used Permission to make digital or hard copies of all or part of this work for personal or classroom use is granted without fee provided that copies are not made or distributed for profit or commercial advantage and that copies bear this notice and the full citation on the first page. To copy otherwise, or republish, to post on servers or to redistribute to lists, requires prior specific permission and/or a fee. Group ’01, September 30-October 3, 2001, Boulder, Colorado. Copyright 2001 ACM 1-58113-000-0/00/0000…$5.00. interchangeably. However, while the GSS term can be seen to incorporate a wide range of collaboration technologies, we will here use the term EMS for GSS technologies specifically designed to provide structured process support for group meetings. These systems include a combination of communication and process support features, often referred to as "level 2" GSS [6]. While laboratory experiments have been the dominating approach in EMS research, a recent literature review documents how the number of case and field studies has increased over the last years [9, 10]. Most of these studies focus on the effects of using this technology on organizational group processes and task outcome. That research shows that the overwhelming experience with EMS supported meetings is positive. Despite this success, few researchers have studied adoption and diffusion of this technology within organizations. A likely reason is the relatively limited proliferation of these systems in organizations. Compared to other collaboration technologies such as Lotus Notes, with an extensive user base and a growing body of accumulated field research [13], EMS have yet to experience the same uptake and focus by companies. However, the increasing number of new web-based EMS products entering the market can be expected to result in a more widespread diffusion of this technology. The prospect of increased use, in combination with the large potential for improving teamwork represented by EMS, leads us to argue for the importance of building knowledge related to the successful implementation of these technologies. The research presented here takes on an exploratory, case study approach to identify issues of importance for the adoption of electronic meeting support technologies. The empirical basis is an in-depth study of the organizational implementation of EMS in Statoil, a large Norwegian oil company. Over a five-year period, Statoil has been implementing GroupSystems fairly successfully, although the diffusion has been slow, and often rocky. One important factor in this technology adoption has been the larger collaborative technology infrastructure, in Statoil, comprising Microsoft NetMeeting, videoconferencing and Lotus Notes, in addition to GroupSystems1. These complement one another to support a wide range of collaboration, including truly "anytime/anyplace" meetings. This portfolio of collaboration technologies, however, has also introduced various competitive 1 Trademark is implied when referring to these technologies in the rest of the paper. Lotus Notes is sometimes abbreviated "Notes", while Microsoft NetMeeting is referred to as just "NetMeeting". effects. With the increasing integration of different technologies towards so-called anytime/anyplace infrastructures it becomes more warranted to study entire portfolios of collaborative technologies, and how their adoption processes interrelate. This study will highlight important inter-relationships at Statoil. The next section reviews the literature related to field studies of organizational implementation of EMS, followed by a presentation of the research approach applied for this study. We then provide a case study description, including a presentation of the case company, and an account of the adoption trajectories for the different collaboration technologies in Statoil. Findings from the case study are analysed and discussed, focusing on issues of importance for the EMS adoption and diffusion in this case. The final section presents our conclusions and implications for practice and further research. 2. LITERATURE REVIEW Most of the existing EMS research is laboratory experiments, focusing on the impact of EMS use on group processes and outcome [8]. Although there is a growing body of field studies, the majority of these are also focusing more on group impacts of the technology rather than the process related to organizational implementation of this technology [9, 10]. Table 1 lists some examples of studies within this category. The findings from these studies show how EMS to various degrees improve the groups’ performance. Contrary to much of the experimental research, field studies of EMS use substantiated a generally high rate of success [9, 10]. However, the focus and research context of these studies limits their ability to provide insight into the process related to organizational adoption and diffusion of this technology. The unit of analysis in these studies is at the team level, with most studies focusing on the appropriation of the technology by permanent teams. Further, the studies often include the use of an EMS facility supported by a third party [e.g. [24]), or the installation of the EMS is only of a temporary nature (e.g. [5]). Thus there is limited availability of field studies addressing the organizational adoption and diffusion of EMS technologies, and we have only been able to identify a few studies with this explicit focus. decision making in the World Bank. The implementation process can be described as a stepwise process lasting over a period of five years, and involving mutual learning between technologists and organizational developers. Several features of the implementation process are stated to have contributed to its success: a high level champion from the organizational behaviour department (ORG), resulting in a focus on the technology as a tool in organizational development a close collaboration between the ORG department and the IT department, resulting in an “unusual degree of sociotechnical balance” a real user design/implementation team comprising twelve carefully chosen members that were to become facilitators and technographers a focus on learning implementation and training throughout the Grohowski et al. [11] describe one of the earliest major adoptions of a GSS by an organization, IBM. Over three years, GroupSystems spread from one single site to 33 sites, used by over 15,000 participants through the company. By tracking the results of a sampling of meetings they substantiated very positive results. Based on these experiences they identified a set of success factors for organizational implementation, examples of which are organizational commitment, the need for an executive sponsor, training, facilitation support, dedicated facilities, cost/benefit analysis and meeting managerial expectations. Finally, Post [21] reports the design and results of the evaluation study conducted by Boeing prior to their decision to purchase TeamFocus (the predecessor of GroupSystems). This involved the creation of a comprehensive `evaluation infrastructure`, including a dedicated evaluation team of ten people serving various roles, development of extensive metrics for measuring business case parameters, technical infrastructure development and facilitator training. The results from the evaluation period documented dramatic improvements in efficiency and effectiveness, and illustrate the value of applying a business case approach to technology evaluation for documenting the benefits from EMS technology. Bikson and Eveland [1] present a sociotechnical analysis of the successful implementation of GroupSystems for supporting group Table 1. Examples of field studies of EMS impact on teams Author (year) [ref.] Focus of study /research context Research approach Caouette and O’Connor, (1993) [3] Impact of EMS on the development of two teams in a US insurance company Quasi-experimental field study Davison and Vogel (2000) [5] Use of EMS for supporting a reengineering process in an accounting firm Action research DeSanctis et al. (1993) [6] Adaptation of an EMS by three teams within the IT department of Texaco Interpretive analysis based on Adaptive Structuration Theory Tyran and Dennis (1992) [24] Application of EMS to support strategic management, based on eight cases involving five organizations using the same EMS facility Multiple case studies This study will extend the above research in two ways. First, it involves a set of conditions that represents a mix of successful and unsuccessful approaches, as identified by the prior studies. Thus, this case adds support or questions about the importance of some of those approaches. Second, it adds a new factor, how EMS adoption and diffusion is affected by concurring organizational processes related to the implementation of other collaborative technologies. Presumably, the growing diffusion of various collaborative systems in organizations suggests the importance of this factor. 3. RESEARCH METHOD A case study approach was chosen for being able to capture indepth, contextual data related to a longitudinal process. Statoil was chosen on the basis that it is the major user of GroupSystems in Norway, and that the company also has extensive experience with deploying this technology in combination with other collaborative technologies. The first author has also conducted prior research in this company on their implementation and use of other collaboration technologies [16]. Table 1 illustrates the large variety in research approaches applied in previous EMS field studies. Overall, few exemplar studies exist that may be applied as a basis for the design of this exploratory research regarding theoretical foundation. Thus, rather than seeking a particular theoretical perspective within which to frame this study, our inquiry has been more in line with a grounded theory approach [23] where categories emerging from our data are being compared and contrasted with findings from previous research in order to extend existing knowledge related to the phenomenon under investigation. Data was collected through five semi-structured interviews, with employees in different roles related to the adoption and use of GroupSystems. The informants, profiled in Table 2, were selected for their key decision making and/or implementation roles, in order to address the rationale behind the main decisions and actions taken. to-face or by telephone lasting from forty-five minutes to two hours. All interviews were taped. The analysis of the interview transcriptions focused on developing a historiographic description of the organizational implementation of different collaboration technologies in Statoil, and identifying key factors influencing the adoption and diffusion of GroupSystems. The case analysis was distributed to the informants for validation of factual information and discussion of the researchers` interpretations, leading to further modification and refinement of the analysis. 4. CASE DESCRIPTION 4.1 Presentation of case company Statoil is a Norwegian state-owned oil company with 17,000 employees and a 2000 operating revenue of over US $ 21,7 billions. The organization comprises 40-50 different sites, including offshore platforms and operations in more than 20 countries. Statoil IT is the organization's central IT unit, responsible for delivering IT services to internal customers in the company. The unit has about 450 employees and is represented at all major Statoil sites. The geographic distribution makes Statoil’s operations coordination-intensive. As shown in Table 3, the company is an advanced user of different IT applications for supporting communication and collaboration. With a full company license, Statoil is one of the world's largest users of Lotus Notes. Statoil is also currently expanding its collaborative solutions to include web-based employee workspaces, virtual collaboration rooms and data conferencing with external parties [17]. Table 3. Statoil Portfolio of Collaboration Technologies Tool Collaborative Features Lotus Notes E-mail, Document management, Workflow, Electronic archive, Group calendar, News and bulletin boards, Discussion databases NetMeeting Application sharing, presentations GroupSystems Supporting structured electronic meeting interactions (co-located and distributed) Meeting Rooms Audio and videoconferencing, meetings, presentations Table 2. Informant profiles Informant Role related to adoption of GroupSystems Project leader/ facilitator Project champion in GroupSystems implementation. Also project leader for implementation of Lotus Notes and Microsoft NetMeeting. Facilitator Statoil IT employee with extensive facilitation experience, for IT and non-IT groups, since the initial introduction of the tool. Facilitator/ product manager Statoil IT employee with extensive facilitation experience. Product manager for the area termed "Facilitation of IT-supported collaboration". User/ facilitator Employee outside of Statoil IT who has used the tool extensively, as well as facilitated groups. User/manager Member of the IT management team. Responsible for approval of the GroupSystems acquisition. The interviews focused on the informants` role in the implementation of GroupSystems and other collaboration technologies in Statoil, their experiences from this implementation including factors inhibiting or supporting adoption, and their reflection about further diffusion of these technologies in Statoil. Interviews were conducted either face- electronic The company started to use IT for supporting meetings when GroupSystems was first installed in 1996. Statoil IT has now established three permanent electronic meeting rooms at the major office locations in Stavanger, Bergen and Trondheim. Each room has a capacity of 12-15 participants, and is equipped with laptop PCs as workstations, audio- and video-conferencing equipment, and public screen projection. Statoil has a pool of around 10 GroupSystems facilitators, largely comprising employees in Statoil IT. The company runs internal courses in facilitation with GroupSystems, based on the vendor's training methodology. Statoil IT rents the electronic meeting rooms and facilitators to other units in the company on an hourly basis. In 1999, GroupSystems was made available over the company network, enabling distributed meetings involving two or more linked meeting rooms as well as participants using GroupSystems from their office. These distributed meetings are usually also supported by audio, video and Microsoft NetMeeting in different combinations, thus providing Statoil’s employees with an 'anytime/anyplace' meeting infrastructure. 4.2.1 In the following, the implementation trajectories for these different technologies are summarized, illustrating how these have been interrelated in several ways. Installation and training 1992-1997 Deployment support 1996-97 Prestudy of EMS tools Implementation of web-publishing tool Trial lease st 1 meeting room establ. Live demo at "I-days `96" Facilitation courses. nd 2 meeting room established Purchase of company license Implementation of webproduction tool for external collaboration Sarepta team established Team for IT supp. meetings established NM integrated in two meeting rooms NM made available 1995 1996 1997 1998 The implementation of Lotus Notes The basis for the adoption of GroupSystems can be traced back to Statoil’s experience from the adoption and use of Lotus Notes. Notes was first introduced in Statoil in 1992, after an initiative from a unit responsible for PC support. The initial diffusion of Notes can best be described as a bottom up process, without any clear overall strategy or coordination. First in 1994, a formalized implementation project was launched, involving the four major units in Statoil. Statoil IT then developed a package of seven standard Notes tools (listed in table 3) and marketed these to the different units in Statoil. Notes spread quickly throughout the organization, with the number of users increasing from approximately 1,000 in 1994 to more than 18,000 in 1997 [15], implying full coverage among Statoil’s employees. However, the actual adoption of the different tools Full integration of audio & video rd conf. and GS. 3 meeting room established Lotus Notes/ Domino Integrated team for e-collaboration established GroupSystems (GS) Integrated team for e-collaboration established Microsoft NetMeeting (NM) NM campaign 1999 2000 2001 Figure 1. Time line indicating major events in the implementation of collaboration technologies in Statoil 4.2 Implementation trajectories Similar to other cases of organizational implementation of collaboration technology (e.g. [1, 20]), the adoption and diffusion of EMS in Statoil has been a lengthy, evolutionary process, comprising a number of incremental steps. Further, the assimilation of this technology can be seen as closely interrelated to the implementation of other collaboration technologies in Statoil. Figure 1 illustrates this by presenting a time line indicating the major events in the implementation of three major technologies in Statoil: Lotus Notes, GroupSystems and Microsoft NetMeeting. showed different patterns. While the support tools enabling oneto-many communication (e-mail, group calendar and news databases) were used extensively, the applications requiring input from each user in shared databases were slower in adoption. A follow up project initiated in 1996 focused on development of routines for effective use of Notes, though with modest success. In 1998, the tools for document management, workflow and electronic archive were merged into a common solution called Sarepta, offering an "electronic project room". As part of this a dedicated Sarepta team was also formed with responsibility for installation of the Sarepta tools and related support. With the functionality for web integration offered by the Lotus Domino server, there has also been increasing emphasis on using Notes as the platform for developing web-applications for internal and external collaboration. struggle continually challenged the EMS implementation. As expressed by one of the facilitators: Statoil IT soon found that Notes was not able to support the collaborative group processes taking place in meetings. As expressed by the project leader for the Notes introduction: "We have had a 'competitor' in Statoil’s Research Centre that worked with partly the same areas, but had more of an exploratory approach, exploring the technology areas. But they also sold to customers in Statoil, so they were like a half competitor on some sub areas. And they did not see any benefit from this [GroupSystems]." "When working with Notes I realized the possibilities and limitations of this tool for collaboration. There were several aspects and processes of coordination and collaboration that were not supported by the standard tools in Notes. This especially relates to meetings, which is the dominating form of collaboration in Statoil. It occurred to us that meeting support tools would be the next step if we were to come further". 4.2.2 The implementation of GroupSystems In 1995, the Notes introduction project leader got the IT department to approve a pre-study of potential meeting support technologies. This person is referred to here as the ’project champion’ [22], due to his major role in the implementation of GroupSystems in Statoil. In January 1996, a consulting company marketing GroupSystems introduced Statoil IT representatives to another Norwegian customer already using the technology. A demo for the managers in Statoil IT was held at the location of this company, creating an "overwhelmingly positive attitude" towards the tool. This was followed up with a live demo at the annual IT seminar in Statoil (the "I-days ’96"), with a large stand and a demo room set up with 15 participant work stations and a LiveBoard. This demo was also described as a success, exposing the product to a lot of people and also enrolling new allies such as the person responsible for new product development in this area in Statoil IT. Despite this, however, the initial proposal to purchase GroupSystems was rejected by the Product Council in the IT department, allegedly due to the costs. The project champion continued working with the proposal and later that year gained approval for entering a half-year lease arrangement with GroupSystems, as a trial period. Soon after this the first meeting room was established at the Statoil headquarters in Stavanger, and the project champion started working full time as a facilitator. He also took on the responsibility for conducting internal marketing of the services, running demonstrations and making a presentation brochure and posters. However, the marketing was only local to this specific site, as this was more than enough demand for one facilitator working full time. The project champion designed an evaluation scheme in the form of a questionnaire to be completed by the participants after each meeting. The results from this evaluation were very good, and were used as the basis for a proposal to purchase the technology at the end of the test period. This was approved, and in March 1997 Statoil purchased a full company licence of GroupSystems. During summer 1997 several facilitation courses were run by an external consultant. At the same time, the second meeting room in Trondheim was established, and a second facilitator was employed so that there was one at each meeting room. Despite this progress in establishing an EMS infrastructure, the activity dropped somewhat in the following period for three main reasons. First, the project champion explained that exhaustion from the work with obtaining the approval was a factor. Another was that internal competition and political However, in general this competitive relationship was also stated to have a positive effect in driving further the establishment of new collaborative solutions within Statoil. A third reason that GroupSystems activity slowed was that Microsoft NetMeeting was launched as a potential new product for Statoil, and the project champion was asked to take on the role of project leader for the development of this product. 4.2.3 Implementation of NetMeeting Although not particularly excited by this technology, the project champion agreed to this assignment. He saw this as an opportunity to influence the further development of meeting technologies in Statoil, and secure the integration of these: "There was very much focus on this [NetMeeting], as this was cost reducing - I did not think this was very exciting, though. And it isn't, it is a very trivial tool that does not influence collaboration at all, but enables us to share information, and share single user tools. Anyway, I was politically allocated to this, it was necessary, it could not be avoided, so it was better to take the initiative and get control over it. I could have just continued to work with GroupSystems, but then we would not have been able to do the merging of the technologies". The role of product manager for NetMeeting temporarily shifted the project champion's focus away from GroupSystems, as most of 1998 went with planning the implementation of NetMeeting. Early 1999 he was central in a big marketing campaign for NetMeeting, aimed at reducing travel costs for the company. As a result of this campaign, the project champion received the "I prize ’99" for the best IT application in Statoil during the "I days ’99", on behalf of the team responsible for the implementation of NetMeeting. The project champion comments the following about receiving this award: "I thought, now we have succeeded in this, now we can return to work on what's more important". 4.2.4 Integration of meeting support technologies GroupSystems, in its early implementation, was regarded as a competing product by the groups responsible for other collaboration technologies. This is illustrated by the fact that during the "I days ’96" the team responsible for audio and video conferences had a separate stand next to the GroupSystems stand, without any collaboration between these two. In line with his integration strategy, the project champion took the initiative to form a dedicated team for IT supported meetings. "It took a year to establish collaboration and break down barriers between these environments. This finally culminated with a team that included representatives from both camps". This team was established in 1998, with him as the leader, and comprising both technical personnel responsible for maintaining and running the solutions, and those delivering facilitation (12 people in all). According to the project champion, the composition of this team was just right: “It was a very good team because we got good synergy from having both technological and method/tool competence in the same team. It was a combined management and delivery team, and that was fully needed in this stage.” In 1999, a third electronic meeting room was established at Statoil’s offices in Bergen. All three meeting rooms were also upgraded to include full integration of audio and videoconferencing, NetMeeting and GroupSystems. 4.2.5 Current level of adoption and diffusion In the time period since then, GroupSystems has been used regularly at the company headquarters in Stavanger. The other two meeting rooms are not used to the same extent, due to the limited access to facilitators. A fourth meeting room, in Oslo, was dismantled after only a short time for the same reason. Recruiting facilitators has been and still is a major bottleneck. Despite extensive internal training of facilitators, involving more than 100 participants, only a handful of these continue to practice as facilitators. According to those responsible for the courses, the recruitment difficulty has much to do with the selection of participants for these courses. Treating this course as ’any other’ internal course, the selection of attendees has often been quite random, without these having any special motivation for learning these skills. Besides motivation, becoming a facilitator may also be seen to require a special blend of personal characteristics. As expressed by one of the instructors: "It requires a form of ’call’. You must have strong interests in this, and you need to have some specific personal characteristics. It is a big threshold. It is challenging in all ways: you both need to understand the tool use, you need to understand collaboration, you must be able to lead a group, it’s a very challenge role to enter into, especially when you both need to master the technology, a rather advanced, universal tool with infinite possibilities that is quite hard to learn – you both need to know about methods for problem solving and collaboration. People have been scared off, I think." In general, GroupSystems is mostly used internally in the IT department, and the diffusion to other units in Statoil has been slow. The marketing has also been limited, due to the limited access to facilitators and meeting rooms. As the capacity for facilitation services has been fully deployed, there has not been a need for selling the technology to new customers. However, one of the informants thinks the internal marketing of the technology could have been better: "I think we would have more requests for facilitation services if we had been better at selling and telling about the benefits from using it [GroupSystems]. We have not been explicit enough about what we deliver". He characterizes the marketing so far as "we`ve got this great tool, do you have any problems for us?" rather than focusing more on organizational needs and then introducing GroupSystems as a potential tool for solving these. In their attempt to diffuse the technology outside Statoil IT, Statoil IT has made several initiatives to build alliances with other units that stand out as natural users of this technology. For example, there is a unit in Statoil called "Change support" that facilitates processes for management, e.g. related to strategy development. However, this influential unit has not been very receptive to the technology, holding on to their traditional, manual facilitation techniques and thus partly acting as a competitor to the services provided by the IT department. In general, several of the managers have also been reluctant to use GroupSystems. One of the facilitators reflects about this in the following way: "I have used the term `holy cow` about meetings, in the sense that some regard this as an arena that should not be `infected` with technology. Because this is a `free zone`, where you can come to a meeting and drink coffee with the expectations from meeting participants often being very diffuse. This is my claim. And when you start to mess with technology and start talking about making the meetings more effective, then you get someone against you." Despite these problems, the work in Statoil for integrating their collaboration technologies into a portfolio continues at full strength. In 2000, the team for IT supported meetings was merged with the Sarepta team responsible for the standard Notes applications, forming a new team for "e-collaboration". This team now maintains the full responsibility for consultation, implementation, utilization and facilitation related to the collaboration technologies in Statoil. A recent organizational restructuring also brought this team under the same management as the “manual” facilitation unit described above, thus possibly leading to better integration of these services. 5. ANALYSIS AND DISCUSSION In this section we discuss the key issues having emerged from our data analysis, comparing and contrasting these with findings from previous studies on EMS implementation. 5.1 Management support Organizational commitment and the need for an executive sponsor were among the key success factors identified in the study of EMS implementation in IBM [11]. In Statoil, the lack of a sufficiently high-level business sponsor is a major factor in the limited adoption. GroupSystems has not yet gained sufficient interest and backing from either top or lower level management to enable widespread diffusion. Being introduced by Statoil IT, this implementation has not been driven by perceived business needs in the rest of the company. In contrast, the NetMeeting implementation was based on a very clear and identifiable need for reducing travel costs. Thus this technology has received much greater focus than GroupSystems. Explicit management backing and support for this technology is clearly crucial to its success. To gain and keep that support, however, beneficial results from improved collaboration need to be translated into tangible net benefits. 5.2 Role of the project champion Similar to the role of top management support, the important role of the project champion is well acknowledged in the diffusion of innovation literature [22] and EMS adoption studies [1, 11]. Likewise in the Statoil case, the role enacted by the project champion has been crucial. Without his continued belief in this technology, the implementation process would have never survived the many pitfalls of organizational restructuring and internal competition for resources occurring in this process. When the GroupSystems champion was pulled away to champion the NetMeeting project, the rapid initial diffusion was placed on hold and lost ground. On the other hand, the level of the project champion was also a constraining factor. Although having a senior position in the IT unit, the project champion lacked the managerial mandate to allocate resources to the implementation himself. Thus the champion in this case played more of an 'operating sponsor' role [11]. Having a member of the leadership team in Statoil IT, or from Statoil overall, as a continuous executive sponsor would probably have resulted in more focus on this implementation project. 5.3 Formal vs. ad hoc implementation projects Compared to implementing Notes and NetMeeting in Statoil, the GroupSystems implementation has been far more ad hoc. A formal GroupSystems implementation project has never been defined. Without the formal allocations through a project, the implementation was left far more vulnerable, at times being solely dependent on the capacity and energy of the project champion. The relative success of the diffusion of Notes and NetMeeting compared to GroupSystems, illustrates the importance of a formalised and planned implementation project, with related resources allocations and schedules. More directly, many of the same resources—including the project champion— were reallocated to the NetMeeting project without such formal protection. The studies of EMS implementation in IBM and Boeing document how these organizations established extensive, dedicated operations for handling the complex tasks related to the creation of a meeting infrastructure, training of facilitators, customer acquisition and evaluation of business benefits [11, 21]. If Statoil IT had been able to mobilize a similar operation for the GroupSystems implementation, it is likely that this would have resulted in a faster diffusion of the technology. 5.4 Establishing an electronic meeting infrastructure develop trust in the ability of facilitators to understand their business operations and issues. Fjermestad and Hiltz [9] also discuss the availability of facilitators as a barrier to the institutionalization of EMS in organizations. To aid in this problem they argue that future EMS software needs to be constructed so that "an internal group leader or leaders can very quickly (eg. in less than half and hour) learn how to use the software to carry out support functions for the group" (p. 6). Based on our findings from the Statoil case, we will argue that this suggestion represents a too simplistic view on the role of the facilitator. Being an effective group facilitator requires far more than mastering the technology. As expressed by one Statoil facilitator: "to facilitate meetings is heavy, it is mentally tiresome, you often sit in a six or seven hour meeting a whole day and are mentally burnt out afterwards. And then the post session work starts. And then it requires that you are good at handling relations and processes, and are able to take things ad hoc in the meetings as they occur, you need to be interested in getting a meeting to function. It definitely is not left hand work". This is also illustrated by the small percentage of Statoil employees that actually continue with facilitation after having gone through the training. Although it may be possible to design future EMS with functionality that supports the facilitator role to a larger extent, there is no way that all of the skills referred to above can be "built into" the system. We thus agree with Nunamaker [18] in his argument for maintaining a centre of competence in EMS, involving a system of apprentice facilitators in training. This strategy was also implemented in Boeing [21]. 5.5 Integration of services vs. internal competition The Statoil case also illustrates the challenging demands of establishing an infrastructure for electronic meetings. In addition to the necessary software and hardware for running this, it also requires dedicated meeting rooms and facilitator services. Additional tools are needed if this infrastructure is also to enable distributed meetings. The initial implementation of GroupSystems was characterized by internal competition and positioning among various groups promoting "their" technology. This clearly was not an effective utilization of the competence and resources within Statoil IT. Only after the team for IT supported meetings formed, was there an integrated and coordinated effort to deploy the various collaboration technologies for supporting effective meetings in Statoil. The costs related to software were relatively insignificant relative to the investments in new meeting room facilities and hardware, including audio and video conferencing equipment. Even finding a room was a challenge, as the different meeting rooms in Statoil were partly owned by co-located work units. However, the project champion also sees the internal competition as having had a positive effect on the further development of services and methods in the Statoil IT. Without this competition, Statoil IT would have continued to exist in a protected, "monopoly" situation. The informants emphasized, however, that the principle bottleneck was finding and keeping facilitators. As is common in groupware implementations, the challenges are more related to people, than technology [4]. In the extreme, the lack of available facilitators resulted in dismantling the fourth meeting room in Oslo. Also, currently two facilities are operating at less than full capacity due to facilitator availability. Diffusion was also affected significantly by the composition of the facilitation pool. Most of the facilitators come from Statoil IT, which is also the largest user of the electronic meeting system. The IT affiliation may create an obstacle for other areas of Statoil to With the new team for "e-collaboration" a common organization is established for all collaboration services within Statoil. However, being formed through the merger of the two existing teams for IT supported meetings and Notes solutions (the Sarepta team), the composition of this new team internalises some of the competing focus of the former teams. So far, the team activities and focus have been somewhat biased towards the asynchronous, Sarepta tools, thus resulting in less emphasis and development of the services related to synchronous collaboration (including meeting support). 5.6 Building alliances with influence groups The implementation of meeting technologies in Statoil has clearly been a political process, involving a lot of lobbying and positioning by the various interest groups. According to actor network theory, the enrolment of influential alliance partners is of key importance for gaining momentum in a technological implementation [14]. Despite several attempts, Statoil IT has not yet succeeded in building alliances with other units in the company. In comparison, other "opponents" in this process have been found to operate more effectively on the political arena in Statoil. 5.7 Customer acquisition The former studies in IBM and Boeing illustrate the importance of (internal) customer acquisition for building organizational commitment to the EMS implementation [11, 21]. In Statoil, the Notes and NetMeeting technologies gained relatively rapid diffusion and user acceptance. The Notes implementation was characterized as “the system selling itself”. The support tools offered (e-mail, document management and archiving, etc.) had a direct impact on the administrative production processes in Statoil, with easily identified benefits. Still, as reflected by the project champion and also observed in other studies [13, 25], this usage of Notes does not necessarily result in an increased level of collaboration among the employees, Similarly, NetMeeting was introduced with the single aim of reducing travel costs, by supporting data conferencing and application sharing, and not for changing any of the existing collaborative procedures. In both cases, the intended benefits were easily identified and clearly connected to bottom line production processes. The clear and simple messages attracted focus and momentum in the diffusion of the technologies. Statoil IT experienced the process of customer acquisition as more challenging for GroupSystems than any other collaboration technology. EMS like GroupSystems may have a significantly greater impact on the dynamics and nature of the collaboration among group members. Yet, these benefits are more difficult to identify or link directly to productivity measures. Also, to fully realize these benefits one has to experience the technology 'in action'. Furthermore, since few people outside of Statoil IT developed facilitation expertise, there was not a communications means to spell out the benefits in the terminology of non-IT user groups. In comparison, the customer acquisition in Boeing was conducted by the established operation of process facilitators, based on their existing network of customer relations [21]. Three permanent meeting rooms established, with one being used regularly The establishment of a permanent team for delivering services related to IT supported meetings An increased number of facilitators (although still limited) A broadened spectrum of customers Thus, it is only when measured against the more widespread adoption and diffusion of other collaboration technologies in Statoil that the implementation of GroupSystems so far can be characterized as less successful. 6. CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS This case study illustrates how different collaboration technologies may follow different implementation trajectories within the same organization. Compared to the implementation of Lotus Notes and NetMeeting, adoption and diffusion of GroupSystems in Statoil has been an uphill battle. The findings from our study also indicate how the process of establishing a portfolio of collaboration technologies may comprise political struggle and internal competition for resources. The relatively intangible nature of the EMS benefits resulted in less organizational commitment and allocation of resources to the GroupSystems implementation compared to other technologies. This made the role of the project champion even more crucial in the GroupSystems implementation. The recent integration of the services related to collaboration technologies in Statoil is an important step towards achieving a coordinated focus on effective utilization and further development of the technologies, and thus eliminating the basis for competition and resource rivalry. This illustrates the importance of establishing a coordinating body with the responsibility for maintaining an overall view on the potential application of various collaboration technologies within an organization, and the interrelatedness among these. The new team for e-collaboration in Statoil was formed with this purpose. However, the composition of this team still has inherent some of the old "rivalry" regarding technology focus, and a further balancing and reconciliation of this will be needed to fully take advantage of this new organizational unit. Further research needs to continue to explore the conditions under which successful adoption and diffusion of collaboration technologies may unfold. In this it is vital to take on an integrated perspective on how organizations may deploy a portfolio of collaboration technologies rather than focusing on single technologies in isolation. 5.8 Success or failure? Several have pointed to the complexity involved in evaluating groupware systems in an organizational context [2, 11]. The many problems outlined in this paper may give the impression that the implementation of GroupSystems in Statoil has been a failure. However, there are several indicators of successful adoption and diffusion of GroupSystems in this case as well. They have achieved good results with the tool, getting good evaluations from the meeting participants. Further, having experienced the benefits from the technology, the majority of meeting owners return to the meeting rooms for new projects. Other success indicators are: 7. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS We are grateful to the Statoil employees interviewed for sharing their time and experience with us. Bjørn Tvedte and the anonymous reviewers provided useful comments for improving the manuscript. 8. REFERENCES [1]. Bikson, T.K. and Eveland, J.D. Groupware Implementation: Reinvention in the Sociotechnical Frame. In Proceedings of CSCW ’96 (Cambridge MA, November 1996), ACM Press, 428-437. [2]. Blythin, S., Hughes, J.A., Kristoffersen, S., Rodden, T. and Rouncefield, M. Recognising 'success' and 'failure': evaluating groupware in a commercial context. In Proceedings of Group '97 (Phoenix AZ, September 1997), ACM Press, 39-46. [3]. Caouette, M.J., and O’Connor, B.N. The Impact of Group Support Systems on Corporate Teams’ Stages of Development. Journal of Organizational Computing and Electronic Commerce 8, 1, 1998, 57-81. [4]. Coleman, D. Groupware Technology and Applications: An Overview of Groupware, in D. Coleman and R. Khanna (eds.), Groupware Technology and Applications. PrenticeHall, 1995. [5]. Davison, R., and Vogel, D. Group support systems in Hong Kong: an action research project. Information Systems Journal 10, 2000, 3-20. [6]. DeSanctis, G., and Gallupe, R.B. A foundation for the study of group decision support systems. Management Science 33, 5, 1987, 589-609. [7]. DeSanctis, G., Poole, M.S., Dickson, G.W. and Jackson, B.M. Interpretive analysis of team use of group technologies. Journal of Organizational Computing 3, 1, 1993, 1-29. [8]. Fjermestad, J., and Hiltz, S.R. An Assessment of Group Support Systems Experimental Research: Methodology and Results. Journal of Management Information Systems 15, 3 1999, 7-149. [9]. Fjermestad, J., and Hiltz, S.R. Case and Field Studies of Group Support Systems: An Empirical Assessment. In Proceedings of HICSS 2000 (Hawaii, January 2000), IEEE, 1-10. [10]. Fjermestad, J. and Hiltz, S.R. Group Support Systems: A Descriptive Evaluation of Case and Field Studies. Journal of Management Information Systems 17, 3, 2001, 115-159. [11]. Grohowski, R., McGoff, C., Vogel, D., Martz, B. and Nunamaker, J. Implementing Electronic Meeting Systems at IBM: Lessons Learned and Success Factors. MIS Quarterly 14, 4, 1990, 369-82. [12]. Grudin, J. Why CSCW applications fail: problems in the design and evaluation of organizational interfaces. In Proceedings of CSCW '88 (Portland OR, September 1988), ACM Press, 85-93. [13]. Karsten, H. Collaboration and Collaborative Information Technologies: A Review of the Evidence Database for Advances in Information Systems 30, 2, 1999, 44-65. [14]. Latour, B. Science in Action. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, 1987. [15]. Monteiro, E., and Hepsø, V. Infrastructure strategy formation: seize the day at Statoil. In: C. Ciborra (ed.), From control to drift. The dynamics of corporate information infrastructure. Oxford University Press, 2000, 148 - 171. [16]. Munkvold, B.E. Challenges of IT implementation for supporting collaboration in distributed organizations. European Journal of Information Systems 8, 1999, 260272. [17]. Munkvold, B.E. and Tvedte, B. Implementing a portfolio of collaboration technologies in Statoil. In B.E. Munkvold, Implementing collaboration technologies in industry: case examples and lessons learned. Springer Verlag, London, Forthcoming. [18]. Nunamaker, J.F. Future research in group support systems: needs, some questions and possible directions. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies 47, 1997, 357-385. [19]. Nunamaker, J.F., and Briggs, R.O. Lessons From a Dozen Years of Group Support Systems Research: A Discussion of Lab and Field Findings. Journal of Management Information Systems 13, 3, 1997, 163-205. [20]. Orlikowski, W.J. Improvising Organizational Transformation over Time: A Situated Change Perspective. Information Systems Research 7, 1, 1996, 63-92. [21]. Post, B.Q. Building the Business Case for Group Support Technology. In Proceedings of HICSS 1992 (Hawaii, January 1992), 34-45. [22]. Rogers, E.M. Diffusion of Innovations. Fourth Edition. The Free Press, New York, 1995. [23]. Strauss, A., and Corbin, J. Basics of Qualitative Research. Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques. Sage, Newbury Park, CA. [24]. Tyran, C.K., and Dennis, A.R. The Application of Electronic Meeting Technology to Support Strategic Management. MIS Quarterly 16, 3, 1992, 313-353. [25]. Vandenbosch, B., and Gintzberg, M. Lotus Notes and collaboration: Plus ca change…Journal of Management Information Systems 13, 3, 1997, 65-81.