Prof - Faculty Senate

advertisement

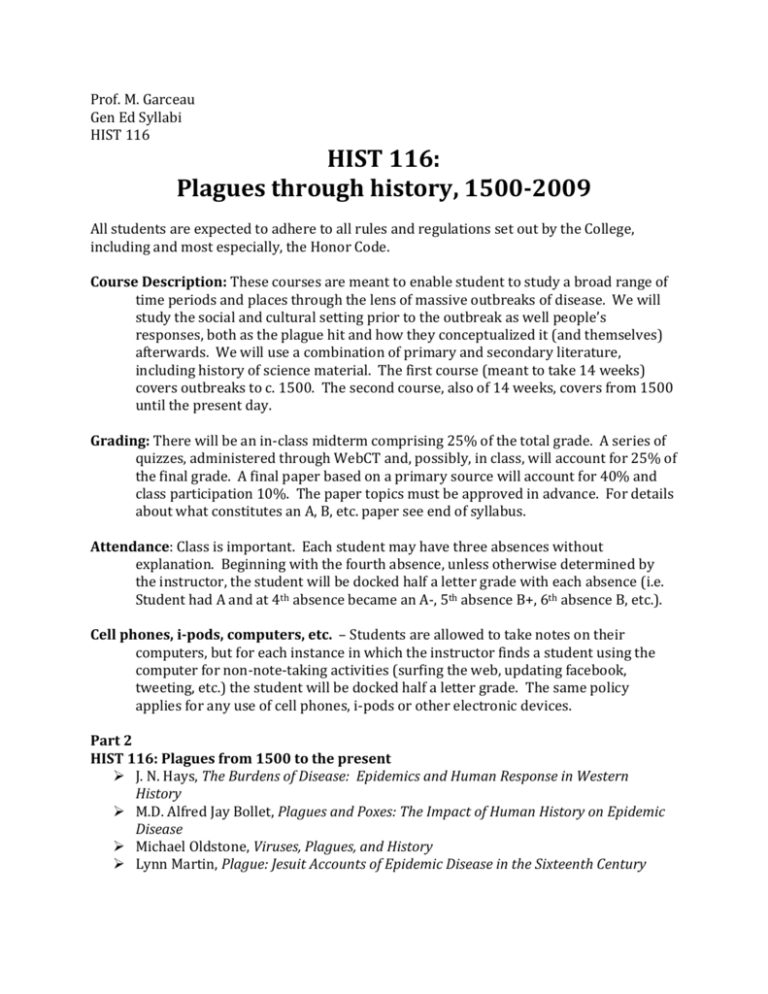

Prof. M. Garceau Gen Ed Syllabi HIST 116 HIST 116: Plagues through history, 1500-2009 All students are expected to adhere to all rules and regulations set out by the College, including and most especially, the Honor Code. Course Description: These courses are meant to enable student to study a broad range of time periods and places through the lens of massive outbreaks of disease. We will study the social and cultural setting prior to the outbreak as well people’s responses, both as the plague hit and how they conceptualized it (and themselves) afterwards. We will use a combination of primary and secondary literature, including history of science material. The first course (meant to take 14 weeks) covers outbreaks to c. 1500. The second course, also of 14 weeks, covers from 1500 until the present day. Grading: There will be an in-class midterm comprising 25% of the total grade. A series of quizzes, administered through WebCT and, possibly, in class, will account for 25% of the final grade. A final paper based on a primary source will account for 40% and class participation 10%. The paper topics must be approved in advance. For details about what constitutes an A, B, etc. paper see end of syllabus. Attendance: Class is important. Each student may have three absences without explanation. Beginning with the fourth absence, unless otherwise determined by the instructor, the student will be docked half a letter grade with each absence (i.e. Student had A and at 4th absence became an A-, 5th absence B+, 6th absence B, etc.). Cell phones, i-pods, computers, etc. – Students are allowed to take notes on their computers, but for each instance in which the instructor finds a student using the computer for non-note-taking activities (surfing the web, updating facebook, tweeting, etc.) the student will be docked half a letter grade. The same policy applies for any use of cell phones, i-pods or other electronic devices. Part 2 HIST 116: Plagues from 1500 to the present J. N. Hays, The Burdens of Disease: Epidemics and Human Response in Western History M.D. Alfred Jay Bollet, Plagues and Poxes: The Impact of Human History on Epidemic Disease Michael Oldstone, Viruses, Plagues, and History Lynn Martin, Plague: Jesuit Accounts of Epidemic Disease in the Sixteenth Century Week 1: Small Pox 1. Chapter 13 “Understanding and Treating Illness” in Natural Science in Western History by Frederick Gregory, 263-84. 2. “A Small-Pox Experience in California” by Ellen Lee in The American Journal of Nursing, Vol. 12, No. 5 (Feb., 1912), pp. 392-395 3. “An Account, or History, of the Procuring the Small Pox by Incision, or Inoculation; As It Has for Some time been practiced in Constantinople” by Emanuel Timonius and John Woodward in Philosophical Transactions (1683-1775), Vol. 29, (1714 - 1716), pp. 72-82 4. “Politics, Prostitution, and the Pox in Revolutionary Paris, 1789-1799” by Susan P. Conner Journal of Social History, Vol. 22, No. 4 (Summer, 1989), pp. 713-734. 5. “Classics of Science: Jenner on Vaccination” in The Science News-Letter, Vol. 15, No. 427 (Jun. 15, 1929), pp. 375-376 6. Pox Americana: The Great Smallpox Epidemic of 1775-82 by Elizabeth A. Fenn Week 2: Sweating Sickness 1. R. S. Gottfried, Epidemic Disease in Fifteenth Century England: The Medical Response and the Demographic Consequences (New York, 1977). 2. Gottfried, "Epidemic Disease in Fifteenth Century England," Journal of Economic History, XXVI (1976). 3. “The English Sweating Sickness, with Particular Reference to the 1551 Outbreak in Chester” by Paul R. Hunter in Reviews of Infectious Diseases, Vol. 13, No. 2 (Mar. Apr., 1991), pp. 303-306. Week 3: The plague of London 1665 1. Samuel Pepys, diary 2. Daniel Defoe, A Journal of the Plague Year 1665 3. “Defoe and the Disordered City” by Maximillian E. Novak in PMLA, Vol. 92, No. 2 (Mar., 1977), pp. 241-252. 4. “Plague and Its Metaphors in Early Modern France” by Colin Jones in Representations, No. 53 (Winter, 1996), pp. 97-127 Week 4: Cholera 1. Letters from W. Field, Postmaster of Little Rock, Arkansas, to Mr. George Jones, West Port, Kentucky, 30 May 1834, University of Arkansas at Little Rock, Archives and Special Collections, B-45, Miscellaneous Letter Collection, Series I, Box 1, File 6. 2. Richard Evens, Death in Hamburg: Society and Politics in the Cholera Years, 18301910. 3. Charles Rosenberg, The Cholera Years Week 5: Yellow Fever 1. “Yellow Fever and the Late Colonial Public Health Response in the Port of Veracruz” by Andrew L. Knaut in The Hispanic American Historical Review, Vol. 77, No. 4 (Nov., 1997), pp. 619-644. 2. “Mass Communication and Public Health: The 1905 Campaign against Yellow Fever in New Orleans” by Jo Ann Carrigan in Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association, Vol. 29, No. 1 (Winter, 1988), pp. 5-20 Week 6: Malaria 1. H. Roy Merrens and George D. Terry, “Dying in Paradise: Malaria, Mortality and the Perceptual Environment in Colonial South Carolina,” in The Journal of Southern History 50:4 (1984), 533-50. 2. “Health, Human Rights, and Malaria Control: Historical Background and Current Challenges” by Paula E. Brentlinger Health and Human Rights, Vol. 9, No. 2, RightsBased Approaches to Health (2006), pp. 10-38 3. “History of Malaria in the United States Naval Forces at War: World War I through the Vietnam Conflict” by Christine Beadle and Stephen L. Hoffman in Clinical Infectious Diseases, Vol. 16, No. 2 (Feb., 1993), pp. 320-329 Week 7: Polio 1. Naomi Rogers, “Dirt, Flies, and Immigrants: Explaining the Epidemiology of Poliomyelitis, 1900-1916” in Leavitt and Numbers, eds., Sickness and Health in America, 543-554. 2. David Oshinsky, Polio: An American Story Week 8: Immigrants and undesirables 1. Kraut, Silent Travelers (selections) 2. Typhoid Mary: Captive to the Public's Health by Judith Walzer Leavitt Week 9: The Great Influenza 1918 1. John Barry, The Great Influenza (selections) 2. News articles from The New York Times a. June 1918 b. July 1918 c. August 1918 d. September 1918 e. October 1918 2. "The Influenza Epidemic and How We Tried to Control It" by Elizabeth J. Davies, R.N., from Public Health Nurse (1919) 11(1): 45-47; 3. "Influenza Vignettes" by Mary E. Westphal, Assistant Superintendent, Visiting Nurse Association of Chicago, from Public Health Nurse (1919) 11(2): 129-32; 4. "A Retrospect of the Influenza Epidemic" by Permelia Murnan Doty, Executive Secretary Nurses Emergency Council, from Public Health Nurse (1919) 11(12): 949-57. Week 10: Syphilis Returns – The Tuskegee Experiment 1. Alland M. Brandt, “Racism and Research: The Case of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study” in Leavitt and Numbers, eds., Sickness and Health in America, 392-404. 2. James Jones, Bad Blood: The Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment Week 11: Ebola 1. Richard Preston, The Hot Zone 2. Richard Preston, “A Crisis in the Hot Zone,” The New Yorker (26 October 1992), 5881. Week 12: AIDS 1. Brandt, “AIDS in historical perspective: four lessons from the history of sexually transmitted diseases” in Leavitt and Numbers, eds., Sickness and Health in America, 426-434. 2. Brandt, No Magic Bullet (selections) 3. Hymes, K.B., Greene, J. B., Marcus, A., et al. (1981) 'Kaposi's sarcoma in homosexual men: A report of eight cases', Lancet 2:598-600 4. Selected sources on GRID and AIDS 1981-3. Week 13: Swine Flu 1. CDC Website http://www.cdc.gov/H1N1FLU/ 2. http://www.cdc.gov/h1n1flu/background.htm 3. WHO http://www.who.int/csr/disease/swineflu/frequently_asked_questions/about_dise ase/en/index.html 4. NYtimes http://www.nytimes.com/2009/04/27/world/27flu.html 5. http://topics.nytimes.com/top/reference/timestopics/subjects/i/influenza/swi ne_influenza/index.html Week 14: Plague in Modern Literature 1. Stephen King, The Cell Grading An A or A- thesis, paper, or exam is one that is good enough to be read aloud in a class. It is clearly written and well-organized. It demonstrates that the writer has conducted a close and critical reading of texts, grappled with the issues raised in the course, synthesized the readings, discussions, and lectures, and formulated a perceptive, compelling, independent argument. The argument shows intellectual originality and creativity, is sensitive to historical context, is supported by a well-chosen variety of specific examples, and, in the case of a research paper, is built on a critical reading of primary material. A B+ or B thesis, paper, or exam demonstrates many aspects of A-level work but falls short of it in either the organization and clarity of its writing, the formulation and presentation of its argument, or the quality of research. Some papers or exams in this category are solid works containing flashes of insight into many of the issues raised in the course. Others give evidence of independent thought, but the argument is not presented clearly or convincingly. A B- thesis, paper, or exam demonstrates a command of course or research material and understanding of historical context but provides a less than thorough defense of the writer's independent argument because of weaknesses in writing, argument, organization, or use of evidence. A C+, C, or C- thesis, paper, or exam offers little more than a mere a summary of ideas and information covered in the course, is insensitive to historical context, does not respond to the assignment adequately, suffers from frequent factual errors, unclear writing, poor organization, or inadequate primary research, or presents some combination of these problems. Whereas the grading standards for written work between A and C- are concerned with the presentation of argument and evidence, a paper or exam that belongs to the D or F categories demonstrates inadequate command of course material. A D thesis, paper, or exam demonstrates serious deficiencies or severe flaws in the student's command of course or research material. An F thesis, paper, or exam demonstrates no competence in the course or research materials. It indicates a student's neglect or lack of effort in the course.