A White Paper on the Future of Cataloging at Indiana University

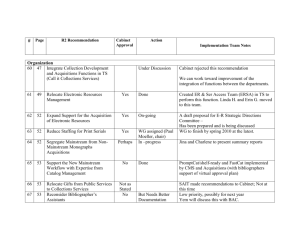

advertisement