303 - American Bar Association

advertisement

303 AMERICAN BAR ASSOCIATION ADOPTED BY THE HOUSE OF DELEGATES February 13, 2006 RECOMMENDATION RESOLVED, that the American Bar Association supports the granting of a permanent injunction enjoining a patent infringer from future infringement of a patent that has been adjudicated to be valid, enforceable and infringed, in accordance with the principles of equity on such terms as the court deems reasonable; FURTHER RESOLVED, that the Association opposes consideration of the extent to which the patent owner has practiced the patented invention or has licensed others to do so, except when determining whether grant of a permanent injunction would adversely affect public safety, public welfare, the national security, or the like. 303 REPORT The Section of Intellectual Property Law asks for approval by the House of Delegates of this Report and Recommendation, which will support the Section’s request for approval for the Association to file a brief amicus curiae in the U.S. Supreme Court in support of the respondent in the case of eBay Inc. v. MercExchange L.L.C., No. 05-130 (“eBay”). This report is being submitted as a late report because the grant of certiorari by the Supreme Court occurred on November 28, 2005, after the November 16 deadline for filing of Reports with Recommendations for consideration by the House of Delegates. The report cannot be considered at a time later than the Midyear Meeting, 2006, since the deadline for filing the amicus brief in the Supreme Court is March 10, 2006. The Recommendation is that the Association support the granting of a permanent injunction enjoining a patent infringer from future infringement of a patent that has been adjudicated to be valid, enforceable and infringed, in accordance with the principles of equity on such terms as the court deems reasonable. The Recommendation further supports the granting of a permanent injunction enjoining patent infringement by the infringer in all such cases of adjudicated infringement, “except in rare instances, such as where the injunction would adversely affect public safety, public welfare, or the national security.” Finally, the Recommendation expresses the opposition of the Association to consideration of the extent to which the patent owner has practiced the patented invention or has licensed others to do so, except when determining whether grant of a permanent injunction would adversely affect public safety, public welfare, or the national security. The Council of the Section of Intellectual Property unanimously approved this resolution and the accompanying report on February 3, 2006. The Section believes that the resolution supports the granting of permanent injunctions in patent infringement cases in a manner that is consistent with existing statutory law (35 U.S.C. 283) and jurisprudence of the U.S. Supreme Court and U.S. Courts of Appeals, including in particular the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (“the Federal Circuit”), which has jurisdiction of all appeals in patent cases. Specifically, the Section believes that the Federal Circuit correctly decided MercExchange L. L. C. v. eBay, Inc., 401 F.3d 1323 (Fed. Cir. 2005). Accordingly, the resolution expresses policy that supports the filing of a brief amicus curiae in support of the respondent MercExchange L.L.C. in the eBay case. The Copyright and Patent Clause of the Constitution, Art. I, §8, cl. 8, provides “Congress shall have Power … [t]o promote the Progress of Science and Useful Arts by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries.” In furtherance of this power, Congress has enacted statutes that provide means by which inventors may enforce the exclusive rights called for in the Constitution. 303 Section 154 of title 35, United States Code, establishes the patent right as a right to exclude others from making, using, selling or offering to sell, or importing the patented invention: Section 154. Contents and term of patent; provisional rights (a) In General. (1) Contents. - Every patent shall contain a short title of the invention and a grant to the patentee, his heirs or assigns, of the right to exclude others from making, using, offering for sale, or selling the invention throughout the United States or importing the invention into the United States, and, if the invention is a process, of the right to exclude others from using, offering for sale or selling throughout the United States, or importing into the United States, products made by that process, referring to the specification for the particulars thereof. Section 271 defines acts of infringement: Section 271. Infringement of patent (a) Except as otherwise provided in this title, whoever without authority makes, uses, offers to sell, or sells any patented invention, within the United States or imports into the United States any patented invention during the term of the patent therefor, infringes the patent. (b) Whoever actively induces infringement of a patent shall be liable as an infringer. Section 283 provides for the issuance of injunctions to prevent the violation of patent rights: Section 283. Injunction The several courts having jurisdiction of cases under this title may grant injunctions in accordance with the principles of equity to prevent the violation of any right secured by patent, on such terms as the court deems reasonable. In Continental Paper Bag Co. v Eastern Paper Bag Co., 210 U.S. 405 (1908) , a leading case on the law of injunctions in patent cases, the Supreme Court reviewed the Court’s previous jurisprudence, and observed: “It shows that, whenever this court has had occasion to speak, it has decided that an inventor receives from a patent the right to exclude others from its use for the time prescribed in the statute. 'And, for his exclusive 3 303 enjoyment of it during that time, the public faith is pledged.' Chief Justice Marshall in Grant v. Raymond, 6 Pet. 242, 243, 8 L. ed. 384, 385. And, in Bloomer v. McQuewan, 14 How. 539, 14 L. ed. 532, Chief Justice Taney said: 'The franchise which the patent grants consists altogether in the right to exclude everyone from making, using, or vending the thing patented without the permission of the patentee. This is all that he obtains by the patent.' “ The right of exclusion is not only indispensable to the vindication of the rights of a patent holder, but it is indispensable to the effective implementation of the power granted to the Congress in the Patent and Copyright Clause of the Constitution. In Kewanee Oil Co. v. Bicron Corp., 416 U.S. 470, at 480, the Court described how the right to enjoin a patent infringer drives the constitutional objective of promotion of invention: The stated objective of the Constitution in granting the power to Congress to legislate in the area of intellectual property is to "promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts." The patent laws promote this progress by offering a right of exclusion for a limited period as an incentive to inventors to risk the often enormous costs in terms of time, research, and development. It follows from the nature of the right to exclude that injunctive relief is absolutely essential to assure the prevention of future violation of the patentee’s rights. Money damages alone cannot suffice. As the Supreme Court noted in Continental Paper Bag Co. v Eastern Paper Bag Co., It hardly needs to be pointed out that the right [of the patentee] can only retain its attribute of exclusiveness by a prevention of its violation. Anything but prevention takes away the privilege which the law confers upon the patentee. (Emphasis added.) The Section of Intellectual Property Law believes that the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit correctly invoked the rule and reasoning of Continental Paper Bag Co. in reversing the District Court’s denial of an injunction in the eBay case, where it stated Because the “right to exclude recognized in a patent is but the essence of the concept of property,” the general rule is that a permanent injunction will issue once infringement and validity have been adjudged. However, at the same time that the Continental Paper Bag Co. Court recognized the essentiality of injunctive relief to effectuate patent rights, it made clear that the grant of an injunction is not automatic, even following final adjudication of patent validity and infringement. In this regard, the Court’s opinion concluded with the observation Whether, however, a case cannot arise where, regarding the situation of the parties in view of the public interest, a court of equity might be justified in withholding relief by injunction, we do not decide.” 4 303 The Section of Intellectual Property Law believes that a permanent injunction enjoining patent infringement by an adjudicated infringer should be granted except in rare instances, such as where the injunction would adversely affect public safety, public welfare, or the national security. We believe that the Federal Circuit’s statement in eBay that “the general rule is that a permanent injunction will issue once infringement and validity have been adjudged” is consistent with the policy that we advocate. We also believe that it is consistent with Supreme Court and other federal appellate court precedent, and that it is an appropriate starting point in formulating the rules for the administration of injunctive relief in patent infringement cases. The general rule that the Section supports is expressed in the first “Resolved” clause of the Recommendation: RESOLVED, that the American Bar Association supports the granting of a permanent injunction enjoining a patent infringer from future infringement of a patent that has been adjudicated to be valid, enforceable and infringed, in accordance with the principles of equity on such terms as the court deems reasonable; The general rule provides that following adjudication of validity of a patent and its infringement, an adjudicated infringer should be enjoined from future infringement. The resolution further provides that the issuance of (or declination to issue) an injunction should be made “in accordance with the principles of equity and on such terms as the court deems reasonable.” The express adoption of language from section 283 o title 35, U.S. Code, regarding injunctions in patent cases is intended to make clear that our policy does not call for an “automatic rule”, a per se rule,” or an “irrebutable presumption,” in favor of an injunction. Instead the policy supports full compliance with section 283, including application of traditional principles of equity. The Section does not agree with the representation of the eBay petitioners that, “. . . the Federal Circuit has commanded, an injunction must follow automatically without consideration of the traditional prerequisites for the grant of equitable relief. (Reply Brief of Petitioner, p. 1). For example, the Federal Circuit recently affirmed the denial of a permanent injunction after a finding of infringement (presumably because of the traditional maxim of equity that injunctive relief should be denied when it would be impractical to administer). Fuji Film Co. v. Jazz Photo Corp., 394 F.3d 1368, 1380 (Fed. Cir. 2005). The Section believes that the Federal Circuit is applying traditional principles of equity and other requirements for granting equitable relief. The court need not write extensively on routine equitable issues that arise in every patent infringement case in which the patent (a) is not invalid or unenforceable and (b) has been infringed. The Federal Circuit need not rewrite the obvious in most cases in which the patentee has prevailed after trial and is seeking a permanent injunction. The second “resolved” clause in our recommendation addresses exceptions to the general rule: 5 303 FURTHER RESOLVED, that the Association supports the granting of a permanent injunction enjoining patent infringement by the infringer except in rare instances, such as where the injunction would adversely affect public safety, public welfare, or the national security; This portion of the recommended policy calls for exceptions to the general rule of injunctions in patent cases in “rare instances.” This policy expressly recognizes certain circumstances that constitute such rare instances, namely those “where the injunction would adversely affect public safety, public welfare, or the national security.” The inclusion of the prefatory term “such as” before these enumerated circumstances is intended to make clear that these examples are just that, and are not exclusive. Petitioners and their supporters assert—erroneously in our view—that the Federal Circuit has narrowly circumscribed the circumstances that justify the denial of a permanent injunction in patent cases. For example, the Reply Brief of Petitioner on the Petition for a Writ of Certiorari opens with the statement “In their petition, eBay, Inc., and Half-com, Inc. (“eBay”) have demonstrated that the Federal Circuit’s holding in this case set out, with a minor exception for public health risks, an irrebutable presumption that a permanent injunction should follow a finding of patent infringement.” The Section does not agree with this interpretation of Federal Circuit precedent, and the policy that we recommend would not permit it. Historically, there have only been fewer than 40 cases in which a prevailing owner of an unexpired patent was unsuccessful in obtaining a permanent injunction restraining ongoing infringement (except by the United States or its contractors who were supplying the government pursuant to "authorization and consent" clauses). It is true that almost all of those cases involved considerations of public health, safety, or welfare. It is therefore not surprising that the Federal Circuit has cited case law regarding the denial of permanent injunctions that would threaten the public health, safety, or welfare. The Federal Circuit was merely referring to circumstances in which permanent injunctions had been denied in the past -- without suggesting or stating that there could be no other circumstances for doing so in the future. In fact, the Federal Circuit affirmed the denial of a permanent injunction on another ground just two months before the Federal Circuit decided the eBay case. See Fuji Photo Film Co. v. Jazz Photo Corp., 394 F.3d 1368, 1380 (Fed. Cir. 2005). Although the Federal Circuit did not use the traditional words of art, the court affirmed the denial of the permanent injunction in Fuji Film because of the "impracticality of the remedy in equity," which is one of the classic grounds for denying injunctive relief (permanent or preliminary). Fuji Film makes it clear that the Federal Circuit has not adopted any rigid per se rule mandating the entry of a permanent injunction except for reasons of public safety, public welfare, and national security. 6 303 Our recommendation does not limit the denial of a permanent injunction to circumstances of public safety, public welfare, or national security, although they have historically been the common ones. The constitutional purpose of the patent system -- to promote the progress of the useful arts -- is in the public interest; and that purpose would inherently be frustrated by the routine denial of permanent injunctive relief in cases brought by patentees who are not practicing their patented inventions. Since the Federal Circuit was established in 1982, its decisions recognize -- as pre-Federal Circuit cases had recognized earlier -- that the interests of public safety, public welfare, and national security may override the public interest in the full enforcement of a particular patent in a particular case. The pre-Federal Circuit cases include other situations in which permanent injunctions had been properly denied for reasons of equity, e.g., the impracticality of the remedy in equity when a patented invention had been incorporated into a road, bridge, or building -- resulting in the denial of a permanent injunction against continuing infringing use that could only be avoided by abandoning or destroying the completed structure. It is important to recognize that it is not feasible to attempt to statutorily enunciate each and every situation in which the public interest may warrant the denial of a permanent injunction. These circumstances nonetheless will occur, and they are cognizable under both existing law and the policy that the Section is recommending. In the Petition for Certiorari, petitioners eBay, Inc. and Half.Com, Inc. state the Question Presented in the appeal as follows: “Whether the Federal Circuit erred in setting forth a general rule in patent cases that a district court must, absent exceptional circumstances, issue a permanent injunction after a finding of infringement.” We find an equivalence in an exception that calls for a departure from a general rule “in rare instances,” as we recommend, and an exception in “exceptional circumstances,” as the petitioners in eBay represent the position of the Federal Circuit to be. Accordingly, the Section finds the Question Presented to be a fair statement of the case, and we believe that the policy that we are recommending to the Association supports answering that question in the negative. The third and final component of the Section’s recommendation for Association policy regarding injunctions for patent infringement addresses the issue of what if any consideration should be given to whether the patent owner is practicing or “working” the patent: FURTHER RESOLVED, that the Association opposes consideration of the extent to which the patent owner has practiced the patented invention or has licensed others to do so, except when determining whether grant of a permanent injunction would adversely affect public safety, public welfare, or the national security. 7 303 The Section believes that this component of the proposed policy, like all its provisions, is both consistent with existing law, and that the law correctly addresses the issues involved. The eBay Petitioners argue that “additional costs of patent litigation that result from the Federal Circuit’s nearly automatic injunction rule are even more troubling given the proliferation of patent assertion firms or ‘non-practicing entities.’” (Petitioners’ Petition for a Writ of Certiorari, p. 27.) A recent report of the Federal Trade Commission describes non-practicing entities (“NPE’s”) as ones that “obtain and enforce patents against other firms, but either have no product or do not create or sell a product that is vulnerable to infringement countersuit by the company against which the patent is being enforced.” (Federal Trade Commission Report To Promote Innovation: The Proper Balance of Competition and Patent Law and Policy. Chapter 3, p, 38, (2003)). In granting the writ of certiorari in the eBay case, the Supreme Court directed the parties to brief and argue the additional question Whether this Court should reconsider its precedents, including Continental Paper Bag Co. v. Eastern Paper Bag Co., 210 U.S. 405 (1908), on when it is appropriate to grant an injunction against a patent infringer. Since the issue of working the patent was central to the resolution of the injunctions issue in Continental Paper Bag Co., it appears that the Supreme Court is prepared to reexamine the issue of the consideration to be given to whether the owner is working the patent. Many colleges and universities, business organizations, and individuals make inventions, patent them, and seek the patent system's financial incentives by licensing (rather then making and selling) the patented product. The denial of a permanent injunction against extant infringement would profoundly lower (a) the royalty that prospective licensees will be willing to pay for a negotiated license, and concomitantly (b) the "reasonable royalty" that might be awarded by a court pursuant to 35 U.S.C. 284. One who has no risk of being enjoined after infringing a valid and enforceable patent owned by someone who does not make and sell the patented invention has little incentive to avoid infringement or to settle a patent infringement case after commencing infringement. Since a non-manufacturing patentee is seldom, if ever, able to prove actual damages, that patentee's monetary recovery is relegated to the statutory "reasonable royalty" for past infringement; if that reasonable royalty drops profoundly in a world in which no injunction can be obtained, there will be an irresistible monetary incentive to infringe patents. Under these circumstances, an infringer would likely be encouraged to attempt a defense on grounds of invalidity, non-infringement, or unenforceability, knowing that if he loses, the only risk would be a reasonable royalty that may be inconsequential. The eBay petitioners and their supporting amici have used pejorative labeling such as "patent troll" (i.e., the petitioners refer to "'patent assertion' companies" and various of the 8 303 supporting amici use the "patent troll" terminology) – to suggest that the owner of a patent that has been held valid, infringed, and enforceable by the district court and the court of appeals could be a "patent troll." While true "patent trolls" are problematic, a meaningful definition of a "patent troll" is a patent owner asserting a claim of patent infringement that is fundamentally flawed regarding one or more of the substantive issues of validity, infringement, and enforceability -- in an effort to coerce the payment of wholly unwarranted royalties. After a patent has been held valid, infringed, and enforceable and the issue is whether to enter a permanent injunction, the patentee should not be considered to be a "patent troll." For reasons that we have explained, the Section does not believe that, in most cases, the fact that the patent owner is not working the patent by the direct production of a product is a relevant factor in a decision to grant or deny injunctive relief. However, there are circumstances in which it is appropriate to consider the extent to which the patent owner has practiced the patented invention. As expressed in the policy that the Section proposes, it is appropriate to consider the extent to which the patent owner has practiced the invention when such consideration is relevant to determining whether a grant of an injunction would adversely affect public safety, public welfare, of the national security. For example, if the owner of a patent on a critical medicine or medical device either (a) does not make and sell the patented device at all or (b) does make and sell but does not have the manufacturing capacity to supply the market's needs if an infringer were to be enjoined, it would be appropriate to deny a permanent injunction at least until such time that the patent owner or its legitimate licensee can fill the public demand for the product. This policy is reflected in the jurisprudence of the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit. In its decision in the eBay case, the court noted “to be sure, ‘courts have in rare instances exercised their discretion to deny injunctive relief in order to protect the public interest,’” citing Rite-Hite Corp. v. Kelley, 56 F. 2d 1538. 1547 (Fed. Cir. 1995). The decision in eBay identified its decision in Rite-Hite as an application of that principle: “Thus, we have stated that a court may decline to enter an injunction when ‘a patentee’s failure to practice the patented invention frustrates an important public need for the invention,’ such as the need to use an invention to protect public health. Rite-Hite Corp., 56 F.3d at 1547.” The Section believes that, applied to the facts and law involved in the issues relating to injunctions in the eBay litigation, the policy that we are recommended clearly calls for an affirmation of the decision of the Federal Circuit. The eBay case does not present an attractive fact pattern for the infringer's opposition to an injunction against continued infringement. Accepting the facts as presented in the petition papers, eBay knew of the patents in suit before the infringement commenced and sought to buy them (or obtain a license under them), but the parties could not agree on terms -- so eBay chose to infringe. (Indeed, the jury found that eBay's infringement was "willful"; the district judge decided, as a matter of judicial discretion, not to award enhanced damages for the willful infringement, and the Federal Circuit did not reverse 9 303 that decision.) Moreover, plaintiff/respondent MercExchange has another licensee who will not be obligated to pay future royalties if MercExchange does not obtain a permanent injunction against eBay. See MercExchange's brief in opposition at 7. The Federal Circuit concluded that “the district court did not provide any persuasive reason to believe that this case is sufficiently exceptional to justify the denial of a permanent injunction.” In fact, none of the reasons cited by the district court appear to be recognized grounds for denial of an injunction under existing jurisprudence, nor to be new grounds worthy of recognition. The district court first states that “a growing concern over the issuance of businessmethod patents, which forced the PTO to implement a second level review policy and cause legislation to be introduced in Congress to eliminate the presumption of validity for such patents.” The introduction of legislation to change existing law is not a legitimate reason for a district court to take it upon itself to implement that change. Indeed, it seems to underscore the fact that if such a change is to be made, it should be made by Congress. Similarly, the fact that the PTO implements additional review procedures for business method patents, as it has for many categories of patents, does not justify discriminatory treatment of such patents when injunctions are involved. Another reason that the district court gave for denying a permanent injunction was that the case was contentious and that an injunction might lead to protracted and expensive enforcement proceedings. However, as the Federal Circuit noted, “the court’s concern about the likelihood of continuing disputes over whether the defendants’ subsequent actions would violate MercExchange’s rights is not a sufficient basis for denying a permanent injunction.” Still another reason for the district court’s denial of a permanent injunction was MercExchange’s expressed willingness to license the patents. The Federal Circuit correctly reasoned that this is not a basis for denial of an injunction, and that Injunctions are not reserved for patentees who intend to practice their patents, as opposed to those who choose to license. The statutory right to exclude is equally available to both groups, and the right to an adequate remedy to enforce that right should be equally available to both as well. If the injunction gives the patentee additional leverage in licensing, that is a natural consequence of the right to exclude and not an inappropriate reward to a party that does not intend to compete in the marketplace with potential infringers. Conclusion The Section of Intellectual Property Law urges the House of Delegates to approve this Report and Recommendation to establish Association policy supporting a general rule that an adjudicated patent infringer will be enjoined from further infringement, except in 10 303 rare instances, such as where the injunction would adversely affect public safety, public welfare, or the national security. The policy would also opposes consideration of the extent to which the patent owner has practiced the patented invention or has licensed others to do so, except when determining whether grant of a permanent injunction would adversely affect public safety, public welfare, or the national security. Respectfully submitted, E. Anthony Figg, Chair Section of Intellectual Property Law February 2006 11 303 GENERAL INFORMATION FORM Submitting Entity: Section of Intellectual Property Law Submitted by: E. Anthony Figg, Section Chair 1. Summary of Recommendation The recommendation urges the Association to adopt a resolution to establish Association policy supporting a general rule that an adjudicated patent infringer will be enjoined from further infringement, except in rare instances, such as where the injunction would adversely affect public safety, public welfare, or the national security. The policy would also oppose consideration of the extent to which the patent owner has practiced the patented invention or has licensed others to do so, except when determining whether grant of a permanent injunction would adversely affect public safety, public welfare, or the national security. 2. Approval by Submitting Entity The Section Council approved the resolution on February 3, 2006. 3. Has This or a Similar Recommendation Been Submitted to the House of Delegates or Board of Governors Previously? No. 4. What Existing Association Policies are Relevant to This Recommendation and Would They be Affected by its Adoption? None. 5. What Urgency Exists Which Requires Action at This Meeting of the House? The policy expressed in the recommendation will support the Section’s request for approval for the Association to file a brief amicus curiae in the U.S. Supreme Court in support of the respondent in the case of eBay Inc. v. MercExchange L.L.C., No. 05-130. This report is being submitted as a late report because the grant of certiorari by the Supreme Court occurred on November 28, 2005, after the November 16 deadline for filing of Reports with Recommendations for consideration by the House of Delegates. The report cannot be considered at a time later than the Midyear Meeting, 2006, since the deadline for filing the amicus brief in the Supreme Court is March 10, 2006. 12 303 6. Status of Matter The status of the issue is discussed in the preceding paragraph. 7. Cost to the Association (both direct and indirect costs). Adoption of the recommendations would not result in additional direct or indirect costs to the Association. 8. Disclosure of Interest There are no known conflicts of interest with regard to this recommendation. 9. Referrals This recommendation is being distributed to each of the Sections and Divisions and Standing Committees of the Association. 10. Contact Person (prior to meeting) Jack C. Goldstein Section Delegate to the House of Delegates Law Offices of Jack C. Goldstein 16 Sugarberry Circle Houston, TX 77024-7251 Ph: 713-782-7823 Fax: 713-782-9942 jcgoldst@aol.com 11. Contact Persons (who will present the report to the House) Jack C. Goldstein (See item 10 above) 12. Contact Person Regarding Amendments to this Recommendation Jack C. Goldstein (See No. 11 above) During the Midyear Meeting, Mr.Goldstein can be reached at the Hyatt Regency Chicago Hotel, 151 E. Wacker Drive, Chicago, IL (telephone: (312) 565-1234). 13

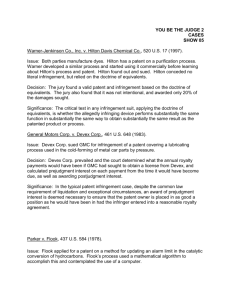

![Introduction [max 1 pg]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/007168054_1-d63441680c3a2b0b41ae7f89ed2aefb8-300x300.png)