The Call of the Wil2

advertisement

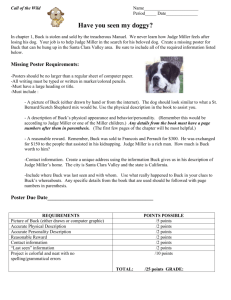

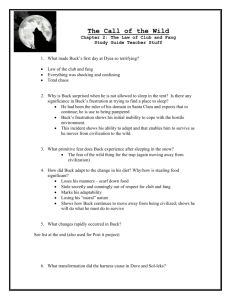

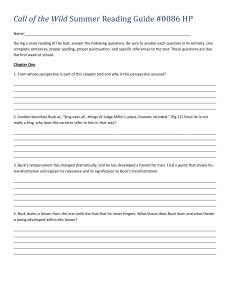

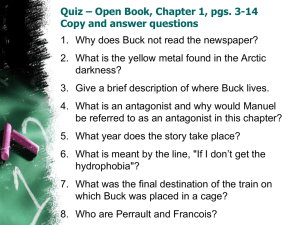

The Call of the Wild Jack London Paul Tansey 1 About the Author Jack London was born an orphan in San Francisco, California, on January 12, 1876, and although he was forced to leave school after graduating from Cole Grammar School (eighth grade) to help provide an income for his family, he was to go on to become one of America’s most prolific and famous writers. The determination and spirit of the characters in his novels are a reflection of his own self-will and adventurous lifestyle. London believed that first hand knowledge was the best source of material for an author, and most of his novels are compendiums of his own experiences. Jack London’s early years were hard. When he was born, San Francisco was a wild and wide open city. Many of its inhabitants had come to San Francisco earlier, in the hope of making a quick fortune when gold was discovered in California in 1848. They had come from all parts of the U.S.A. and many countries, but few found gold. Most had nowhere to go, or no one to return to, or had used up all their meager funds and were unable to return to their homes. Jack’s mother, Flora Wellman, was unmarried when she gave birth to her son. His given name at birth was John Griffith Chaney, named after a man who denied he was the father and disappeared. Eight months after he was born, Flora married John London, and the baby’s name was changed to John Griffith London. The family was very poor and when Jack was eleven he worked as a newspaper delivery boy to help supplement the family’s income. At fourteen he was working in a fish cannery and going to school. He sometimes worked thirty-six hours in a row without going home. Finally, the low wages and excessive hours of work at the cannery proved to be too much for him to handle along with his schoolwork, and he quit school entirely. 2 He bought a small boat after borrowing some money, and for the next year, became a full time oyster pirate, stealing oysters from the oyster farmers in the San Francisco Bay. He became so good at stealing that he was called “The Prince of the Oyster Pirates,” and was later hired by local fishermen to patrol the bay in his sloop to stop others from stealing oysters. He stayed with the “Fish Patrol” for several months but was restless and yearned to travel, and when an opportunity to work on a three-masted, seal hunting, sailing ship that was to travel along the coasts of Japan and the Behring Sea for seven months, came along, he took it. When he returned, he entered an essay contest promoted by a local newspaper, the San Francisco Call. His fellow competitors for the first place prize of U.S. $25.00, a considerable amount of money in 1893, included college students from Stanford University and the University of California. His essay, “Story of a Typhoon off the Coast of Japan,” based on his previous encounters as a sailor, won 1st prize and was published in the newspaper. It was his first published work and first income from writing. He would not have anything else published for six years. He worked at odd jobs for the next year, some paying as little as $.10 per hour. The work was hard and the pay small, and London saw no future in factory work or shoveling coal, so he decided to quit work and see the world. He had little money and, for the next three years, traveled as a vagabond on freight trains around America. He met many colorful characters during his travels, who would later become material for his stories and influence his sociological views. He was arrested for vagrancy in Buffalo, New York and spent 30 days in jail. Soon thereafter, he returned to San Francisco and tried to continue his education, while once again working in the fish canneries. He managed to finish two years of high school and another semester at a college preparatory school before taking, and passing, the entrance exams for the University of California, Berkley. Due to financial 3 conditions and disillusionment with academic life, he only completed one semester at Berkley before returning to Oakland, California to work in a steam laundry. Six months after returning home, Jack and his much older brother-in-law, Captain James Shepard, set out for north-western Canada, where gold had recently been discovered. The terribly harsh conditions in the Yukon forced Shepard to abandon the prospecting expedition after only a few months, while Jack managed to stay for a year before returning home ill and broke. During his stay in the Klondike, London learned a lot about primitive living and daily survival, for only those rough enough and tough enough survived a winter in one of the most formidable places on earth. His wealth of experience gained during his time there became the basis for many of his later stories and novels, including, “The Call of the Wild.” Although London died at a young age (1876-1916), he wrote more than fifty books. He was an internationally accredited novelist by the age of twenty-seven and was the highest paid and most popular novelist and short story writer of his time. 4 The Story Buck was a big, strong, gentle, dog. His father, a huge St. Bernard, had been Judge Miller’s inseparable companion before he was born. His mother was a Scottish shepherd, so Buck wasn’t quite as big as his father, but on the judge’s property, he was the king. There were other dogs that lived at Judge Miller’s place, but it was Buck who lay at the judge’s feet before the roaring fire in the library on cold winter nights and carried the judge’s grandsons on his back. It was the gentle and affectionate Buck who went for long, early morning walks with the judge’s young daughters through the forests that surrounded the judge’s large house. And, it was Buck who went hunting and swimming with the judge’s sons in the valleys and streams of Judge Miller’s place in Santa Clara, California. Yes, Buck was the king of the animals in the judge’s house and on the judge’s property. He was well fed and taken care of and was as content as any dog could be. All of that was to soon change. The year was 1897, and Buck was four years old. Gold had been discovered in Canada’s Yukon the previous year, and many desperate men, driven into a frenzy by the thoughts of instant wealth, had taken what little possessions they had and headed for the frozen tundra of the Klondike. Manuel, one of the gardener’s helpers on Judge Miller’s estate, needed money. Buck was friendly to all those he knew, and when Manuel came to take him for a walk one fall night, he went along docilely. The judge was away on business that night and the boys were busy, so no one saw Manuel lead Buck through the orchards of the property to a small train station. Buck didn’t sense danger until Manuel, after receiving $100.00, passed the rope he had put around Buck’s neck to a stranger on the station’s platform. Buck growled 5 and tried twisting and turning to free himself, but to Buck’s surprise, the stranger kept tightening the rope around his neck. The struggle lasted for several minutes until Buck’s breath was completely cut off and he became unconscious. Buck was sold from one stranger to another, until three days later, after changing trains several times and a short ship passage, the cage in which Buck was kept, was delivered to a fat man in Seattle. Buck had refused to eat for two days and when the cage was placed on the ground, he threw himself savagely against the bars. With his hair bristling, his mouth frothed with white foam, and his red, bloodshot eyes filled with anger, Buck sprang at the fat man when the cage was opened. But the fat man had handled many violent, kidnapped dogs before, and when Buck sprang, he hit him squarely between the eyes with the club he had in his hand. Buck was stunned; he had never been hit like that before. He charged the man again and again with the same results. Finally, with no strength left, he lay on his back panting, and did not react, when the fat man came over and patted him on the head. He knew he was beaten; he could not overcome the club. Although he was beaten, he was not broken. He had learned a valuable lesson about the power of raw, primitive, savage strength, and the power of the club, lessons he would never forget. Perrault was a rather small, swarthy French-Canadian who spoke broken English with a heavy accent and delivered mail by dog sled for the Canadian government. He was in Seattle, with his helper Francois, a huge French-Canadian half-breed, to buy dogs for the new ‘team’ he was putting together. When he saw Buck in the fat man’s high walled back yard, he immediately knew that this was a dog he had been searching for- “‘One in ten thousand,’ he whispered to himself.” He bought Buck for $300.00 and took him and another dog he had bought, a dog named Curley, to a ship that was bound for the Yukon. Below decks of the ship, Buck and Curley joined two other dogs also bought by Perrault. 6 One was a large snow-white dog named Spitz; an experienced sled dog who had been purchased from a sea-captain. He was friendly but two-faced; he would smile at you one minute and steal your food the next. The other dog, called Dave, had a rather taciturn disposition. He showed little interest in the ship or the other dogs; he just didn’t want to be bothered. Dave was prepared to defend his solitude, and the other dogs, sensing this, left him alone. The ship sailed on day and night, and the weather became colder day after day. Finally, the ship stopped and Francois led the dogs ashore. Buck was puzzled by the small white things that kept falling from the sky. He shook himself, but instantly his fur was again covered with the cold, soft flakes. And, when his feet sank into the whitened ground, rather than gaining a grip on a solid foundation, he growled and jumped into the air. When he looked around, some of the onlookers were laughing. It was Buck’s first snow. His next survival lesson came shortly after they left the ship. They had camped next to the wood store in Dyea, a small Alaskan gold rush town, and the first stop for many on their way to the gold fields in the Canadian Northwest Territory. The town was teeming with wild-eyed men, saloons, and the huskies that were needed to pull the heavily laden sleds over the snow covered terrain. Many of the huskies looked and acted like the wild wolves that freely roamed the Alaskan and Canadian wilderness, and in fact, many of them were, indeed, part wolf. Curley, in her friendly manner, approached one of the male huskies. Without warning, the large male attacked Curley, and with one vicious bite, tore her face open and leapt away. Curley was stunned. Buck watched the as the other dogs of the town formed a circle around the fighting pair. Curley was even larger than her attacker but stood little chance. She, like Buck, was a house dog, a pet, and had never learned to fight to the death. The husky charged and knocked Curley off her feet. In that instant, with 7 Curley helplessly on her back, the other dogs lunged at her soft, exposed stomach. It was all over in a matter of minutes, and Curley lay dead on the frozen snow. Everything had happened so quickly, that Buck didn’t have time to react; to help his friend if he could. He was shocked at the suddenness and viciousness of the attack and the absence of fair play. “So, this is the way it’s going to be,” he thought. Spitz had also been watching the fight, and his long tongue hung loosely from his mouth as Curley was knocked down and set on by the other dogs; it was almost as though he was laughing. From that day on, Buck and Spitz were enemies. The next morning Buck was again shocked as Francois strapped and buckled him, Dave and Spitz into the sled harness. He had never been in a harness before, but it reminded him of the harnesses used on the judge’s horses back home. Spitz, the lead dog, was in front of Buck, and Dave was behind him. Both Spitz and Dave were experienced sled dogs, and whenever Buck made a mistake, they nipped and growled at him. Buck was a very smart, and, by the end of the morning, had learned his role in the team and to respond correctly to Francois’ commands. That afternoon, Perrault returned with two more dogs, Billie and Joe. They were brothers but of completely different temperaments. “Billee’s one fault was his excessive good nature, while Joe’s was the very opposite, sour and introspective, with a perpetual smile and a malignant eye. Buck received them in comradely fashion. Dave ignored them, while Spitz proceeded to thrash one and then the other. Billee wagged his tail appeasingly, turned to run when he saw that appeasement was of no avail, and cried (still appeasingly) when Spitz’s sharp teeth scored his flank. But no matter how Spitz circled, Joe whirled around on his heels to face him, mane bristling, ears laid back, lips writhing and snarling, jaws clipping together as fast as he could snap, and eyes diabolically gleaming-the incarnation of belligerent fear. So terrible was his appearance that Spitz was forced to forgo disciplining him; but to cover his own discomfiture he turned upon the inoffensive and wailing Billee and drove him to the confines of the camp.” 8 By evening Perrault had added another dog to the team, an old, one eyed, battlescarred husky who was long, lean and gaunt. His name was Sol-leks, which means “The Angry One.” Sol-leks, like Dave, asked for nothing, gave nothing, and expected nothing. He simply wanted to be left alone. He was old and wise to the ways of the wild, and attacked any dog that approached him on his blind side. When Buck unwittingly made the mistake of approaching him on his vulnerable side, Sol-leks whirled around and slashed Buck’s shoulder to the bone. It was the last time Buck made that error, and they soon thereafter developed a lasting comradeship. Three more huskies, Pike, Dub and Dolly, were added early the next morning, for a total of nine, and Perrault and Francois set out with their team to deliver the mail. Spitz, the leader, was at the head of the team, and Dave, the last dog, was closest to the sled. So that he might learn quickly, Buck was placed between Sol-leks and Dave. Dave and Sol-leks were good teachers and Buck was a serious student and a quick learner. Before the fist day had ended, Buck had learned his work so well that Francois rarely had to strike him with the whip, and Dave and Sol-leks stopped biting him. Day after day they traveled, up through the canyon that led out of Dyea and over the great Chilcoot Divide, which separated the salt water from the fresh, across rivers of ice and banks of snow hundreds of feet deep. Sometimes there was a narrow trail to follow, but mostly, not. With each passing day, Buck became stronger and wiser. He learned to eat his food quickly or have it stolen by the other dogs. He was always hungry even though he was given 1½ pounds of dried fish daily, ½ pound more than the other dogs, and when he was hungry, he learned to steal food, too, just like the others; something he had never done before. His body was getting leaner and his muscles harder. He learned how to dig a shelter 9 in the snow and stay warm by curling his body into a tight ball, even though the temperature sometimes reached 50 degrees below zero, and he often sniffed the wind to tell which way it would blow the following day. When he heard the wild wolves howl, he howled long and wolf-like, too, and long dormant traces of his ancestors began to emerge. He could almost sense his ancestors running in packs through the forests, hunting their prey, just as the wolves did. One night, when they were camped on the shore of a lake, they were attacked by a pack of eighty or a hundred stray, starving huskies. They had smelled the food in the camp and were so desperate for food that, even though they were being beaten with clubs by Perrault and Francois, they continued to eat the bread and meat from the camp’s food box. The team-dogs were fighting the attackers also. Dave, Sol-leks, Joe and Buck were all fighting bravely, against, sometimes, two or three of the wild huskies at one time; and, Billee was crying. Shortly before the attack, Buck had made himself a nice, warm nest as the icy wind whipped through the camp and the driven snow piled high against the rock cliff at his back. When Francois called him for his fish dinner, Buck reluctantly left the warmth of his nest for the meal. When he returned, Spitz, who sensed that Buck was somehow a danger to him, and antagonized Buck whenever and wherever he could, was occupying his nest. Buck sprang at the surprised Spitz, who thought of Buck as a city bred, pet and incapable of viciousness. The two dogs squared off in what would surely have been a fight to the death if it had not been interrupted by the attack on the camp of the wild huskies. As Buck threw off one of the attacking huskies, he felt the teeth of another dog sink into his neck. It was Spitz, attacking him while he was busy fighting off the invaders. When Buck wrested himself away, Spitz tried to knock him onto his back in front of the attackers. 10 That would have been instant death for Buck and he knew it. He gathered his strength and stood firm against Spitz’s assault. Then he ran after the other team-dogs, who had run out onto the frozen lake, knowing that one day, the fight that had been interrupted, would continue. Most of the team-dogs were injured in the fighting but none were killed. Joe lost an eye, and one of Billee’s ears was chewed almost completely off. He cried all night. Dub and Dolly both had serious bites. The attacking huskies had eaten half of the camp’s food supply before being driven off, and were so hungry, they even ate some of the leather straps on the harness. Perrault and Francois were angry and worried. They had lost over half of their food supply and still had four hundred miles to go before they reached their destination, Dawson. The remainder of the journey was difficult and dangerous. Some of the terrain was so treacherous that it took six days to travel only 30 miles. More than once, Perrault, who was walking ahead of the team, had fallen through thin ice, and at one point they almost lost the whole team when the thin ice broke under the sled and threatened to pull all the dogs down. But, they finally reached Dawson with only the loss of Dolly, who went mad after being bitten by the huskies and had to be killed when she started to attack the other team-dogs. The fight that had been coming between Buck and Spitz took place on the return trip to Skagway. The fight was brutal and both dogs fought with tenacity and courage. A pack of 60 huskies from a nearby camp had encircled the area and were watching the fight intently. When Buck broke both of Spitz’s front legs with vicious bites, the fight was over. Spitz continued to growl and snap but knew his death was imminent. Buck made one quick, 11 final attack and it was over. The pack quickly moved in on the kill. Spitz was dead and Buck felt….. good. Buck had won the respect of the rest of the team and became their new leader. All the dogs worked hard for him, and when two new dogs were added, he trained them quickly. The return trip was made in record time, an average of 40 miles per day for 14 days. Perrault, Francois and the record setting team, became the talk of the town for awhile, but soon thereafter, the government transferred both of the men and the team was assigned new drivers. Francois was distraught and tearful as he hugged Buck for the last time, but orders were orders. It was the last time Buck would see either of the two men. New dogs were added, and the 12 dog team, with Buck as its leader, headed once again for Dawson. Buck was a hard worker and a fair leader. He led by example and only disciplined the other dogs when it was absolutely necessary. On the few occasions, early on, when he was challenged by one of the new dogs, who were native huskies and fierce fighters, he defeated them. From then on, all Buck had to do was growl and show his teeth and the others moved away from him; there were no more fights or challenges. Buck thought less and less often about his previous home at Judge Miller’s place and more often about the wild wolves, the freedom of the wilderness, and his ancient ancestors. He felt something primitive stirring within him and slowly rising to the surface. The journey was hard because of new snow, which was soft and made pulling difficult. By the time they reached Dawson, the dogs were gaunt and tired. Most of the team had traveled 1,800 miles since the start of winter and needed a two week rest and plenty of food to regain their strength, before heading back for Skagway. But because of the backlog of mail, the team was returned to the trail after only two days rest. The drivers always treated the dogs fairly, but the mail had to be delivered. 12 Thirty days later the worn out team arrived back in Skagway. This had been no fast, record run across smooth, packed trails, but rather a slow, torturous one over soft, dangerous trails. They had traveled 1,200 miles on only two days rest and had lost a lot of weight. Dave had become sick along the way and had fallen down many times. He had, courageously, tried again and again to assume his rightful place in the team harness but was finally unable to stand; he could only drag himself a short distance. Out of compassion, one of the drivers shot him rather than leaving him to die by the side of the trail, and the team moved on. Most of the dogs were so weak and run down; they were seen as unfit to go on as sled dogs for the mail runs. Three days after their arrival, Buck and the remainder of the team were sold by the government at a very low price. The buyers were Hal, an older man with weak, watery eyes, and Charles, a young man of 19 who carried a big gun and had a hunting knife on his belt. The dogs could barley pull the overweighed sledge, but after continual whipping and beating by a determined Charles, managed to make it to John Thornton’s camp at the mouth of the White River. There, they fell down, exhausted. Charles whipped and clubbed Buck to get him to move, but Buck, near death, didn’t have the strength to go on, and simply accepted the rain of blows without moving. John Thornton, seeing the vicious beating of the helpless Buck, threatened to kill Charles if he hit Buck one more time, and then he cut Buck free of the team harness. Charles gathered the rest of the weary dogs and headed on to Dawson. He had been warned of the danger of thin ice at this time of year, but paid no attention. Before the team had moved out of the sight of Buck and Thornton, there was a loud crack and a hole opened in the ice that swallowed the team, the sledge, and the drivers. All were lost. 13 John Thornton had saved Buck’s life, and Buck became his devoted companion. Thornton was a considerate and caring master and under his watchful eye, Buck slowly gained back his strength. He often thought about the wilderness and being free, but his love for John Thornton continued to grow, and he was reluctant to leave his side. No one dared to hurt Buck’s master when Buck was with him, for it was widely known throughout the Alaskan camps what kind of dog Buck was, after he savagely bit the throat of the last person who shoved Thornton. Buck was exonerated of any blame by the local townspeople at a ‘miners meeting,’ who felt the attack was justified. Later that summer, Buck would again show the depth of his love for John Thornton, when Thornton’s small boat capsized in the swiftly moving rapids of the Forty Mile Creek. He saved his master from certain death by swimming out to him with a rescue rope tied around his neck and shoulders. Buck was seriously injured and almost drowned but he wouldn’t let his master die. ‘Miners’ loved to brag about their dogs and Thornton was no exception. Everyone knew of Buck’s reputation, and when one of them boasted that his dog could start a sled with 500 pounds, and another said his dog could pull 600 pounds, and another 700 pounds, Thornton was forced to defend Buck and said that Buck could start a frozen sled with 1,000 pounds and pull it for 100 yards, something that no dog had ever done. A bet of $1,000.00 was made, money that Thornton didn’t have and had to borrow. Before the contest, Thornton was nervous and doubtful; he wasn’t at all sure that any dog, even his beloved Buck, could manage such a feat. When Buck crossed the finish line, Thornton was so overwhelmed that he fell to his knees beside Buck and hugged his neck while whispering over and over again his love for this great animal. Their bonding was complete. 14 With the money won from the bet, Thornton was able to set out in search of a long lost gold mine. The miners had been talking about the lost mine and an old hut near its entrance, for years, and although many had set out to find it, none had. It was Thornton’s dream that he would be the one to find what nobody else could. That spring, Thornton and Buck, along with Thornton’s two partners, Pete and Hans, and six other dogs set out to fulfill Thornton’s dream. They headed east, away from the established mining towns and camps, then north, up the Stewart River, to where few had ever been. Month after month they traveled, hunting for their food as they went, and camping whenever they felt like stopping. Thornton was a good hunter, and both the men and the dogs ate fresh meat rather than dried jerky or dried fish. They traveled for a year without finding the old hut or the lost mine, but the following spring, they happened on a valley with streams filled with gold. There was so much gold that they put it in 50 pound burlap sacs and stacked them against the side of the small cabin they had built. The men worked every day gathering the gold dust and nuggets but the dogs had little to do. At night, Buck was uneasy when he heard the lonely baying of the wild wolves, far off in the distance. One night the baying of a single wolf was much closer, and Buck was drawn to the sound, much as iron filings are drawn to a magnet. He tried to get close to the gaunt, silvery shape in the moonlight, but the wolf was afraid of the much bigger and heavier Buck, and ran off. Buck followed him, and the two dogs ran for hours through the dark forests and desolate valleys of the northland. Finally, the young wolf approached Buck cautiously, and when Buck didn’t attack, moved close enough to rub noses. They played for awhile, and toward morning, the wolf made signs that he wanted Buck to follow him. Buck ran shoulder to shoulder with his brother canine until they stopped to drink at a stream in the 15 afternoon and he remembered John Thornton. He raced back to camp and didn’t leave Thornton’s side for two days. As fall approached, Buck had taken to spending days at a time away from the camp, hunting and killing his food when he was hungry. It was the time of the year for the moose migration, and Buck watched, with interest, as the herds moved through the area on their way south to warmer winter pastures. He had already killed a young moose that had gotten separated from the others but he now wanted a greater challenge and had his eye on the leader of the band that was passing through, a huge, angry bull-moose that stood over 6 feet tall and weighed over 1,000 pounds. He followed the band for four days and harassed the bull whenever it tried to lie down, eat or drink. Whenever Buck would approach, the bull would lower his head and charge fiercely, but all Buck had to do was to quickly move out of the way and then run in and nip at the bull again. The bull, somewhat weakened by an Indian arrow that stuck from its side and the continual loss of sleep and nourishment, could finally go no further. It offered no resistance when Buck moved in for the kill. Buck stayed and feasted on his prize for a day and a half, thinking of little else but the pleasure and satisfaction of the hunt. When he finally thought of John Thornton, he headed back to the camp. Though he had never traveled this way before, he intuitively knew the direction to the camp and headed straight there. As he got closer to the camp the hair on his back started to rise; Buck sensed danger. The air was too still and the night was too quiet. He crept slowly up to the camp. His anger built as he, first, found several of the dogs either dead or close to death, and then Hans dead with arrows sticking from his back. But when he saw the ruins of the cabin and the Yeehat Indians dancing in front of it, he went crazy. He leapt into their midst and killed the first Indian in seconds by ripping out his 16 throat. He killed and wounded many more before the frightened Indians ran off shouting about the demon that had been unleashed upon them. He found Thornton’s body in a muddy pool near the cabin. He stayed by the pool all that night and into the next day, brooding over the loss of his loving master. The following night was a full moon and as the distant howling and yelping of the wild wolves grew closer, Buck felt the primitive stirrings of his ancestors once again, only this time, there was nothing to pull him back to the world of man; the final ties had been broken with the death of John Thornton. The pack approached wearily and when one of the bold ones leaped at him, Buck broke his neck. Three others tried and met similar fates. Finally, the whole pack attack Buck and he slowly retreated, snapping and biting as he sought a position that would protect his back. When he found a place that offered protection to his back and sides, he turned to face the snarling pack. The fighting continued for half an hour until the wolves were tired and pulled back a short distance. As they lay there watching this fighting demon, one of the younger males moved out of the shadows and approached Buck. It was the gaunt, silver, brother-wolf he had run with during the summer. And, when they touched noses, another older battle-scarred wolf left the pack and came forward to sit down beside Buck. The old wolf lifted his head to the bright moon and started howling. He was soon joined by the rest of the pack and the howling became intense. Then Buck lifted his big head, naturally, and started howling with his brothers. 17 Questions 1. Do you think that the dogs of today retain primitive instincts? Discuss this in a small group and give an oral report to your class. 2. Why do you think the Klondike mail runs were so important? Discuss this with a partner and give an oral report to your class. 3. Many of the ‘miners’ returned home sick and broke. If you were one of them, what would you have done differently? Discuss this in a small group and report your findings to the class. 4. Do you think there is still gold to be found in unexplored regions of the world? Discuss this with a partner and give an oral report to your class. 5. Do you think that Buck could ever return to being a pet? Discuss this in a small group and report back to the class. 6. What do you think happened to all the gold that John Thornton discovered? Discuss this with a partner and give an oral report to your class. 7. Do you think there were other types of transportation used in the Yukon in 1897? What types? Which do you think were the most effective? Why? Discuss this with a partner and give an oral report to your class. 8. $1,000.00 was a lot of money in 1897. How much would its equivalent value be today? Work with a partner. Find you answer in the library or on the internet and report back to your class. 9. Do you think ‘man’ retains primitive instincts? Discuss this in a small group and give an oral report to your class. 18 10. Do you think “The Call of the Wild” is a true story? Discuss this in a small group and give an oral report to your class. 19