canadians under fire

advertisement

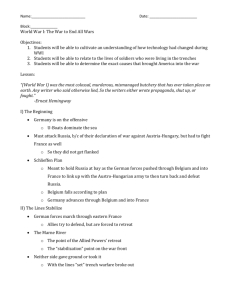

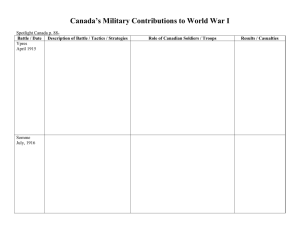

CANADIANS UNDER FIRE TRENCHES The armies’ defense systems were a maze of trenches zigzagging across mud, shell craters, mine fields and barbed wire. The front-line trenches closest to enemy guns were the firing lines. Machine guns were placed at key positions to rake enemy lines with bullets. Three or more lines of support trenches at the rear served as command and supply posts. Running at right angels between them were communication trenches. Sometimes, small trenches called “saps” snaked out to lookout posts or machine-gun nests in no-man’s land. There were also blind alleys to confuse the enemy if the trenches were captured. Duty on the front-line trenches usually lasted six days. Soldiers then fell back to the support trenches for six more days, where their job was to ferry ammunition and food rations up to the front. Then they were taken out of the trenches altogether for twelve days to rest in tar-paper barracks, barns or abandoned villages to the rear of the battlefield. On their tours of duty, soldiers ate, fought and slept in the trenches. In the front line, days were spent standing sentry duty and repairing collapsing trench walls. The front-line trenches were usually about two metres deep by two metres wide and were dug down until water began to seep in. In wet weather, the men on patrol often stumbled through thick mud and slimy water up to their knees. One trooper with the Royal D Canadian dragoons described his first trip through a communications trench to the front line: “The trench was about three feet deep and wound across a swamp and every step squelched as one stepped on one of the bodies that floored the trench. The walls were part sandbags and part more bodies – some stiff with rigour mortis and others far gone with decay”. The trenches were also full of rats and lice. A British officer wrote of the rats, “There are millions! Some are huge fellows, nearly as big as cats. Several of our men were awakened to find a rat snuggling down under the blanket alongside them.” The soldiers often went for weeks without washing or changing clothes, and most were infested with body lice. Others got trench foot from days spent knee-deep in water. Their feet swelled up to two or three times their normal size and went numb. “You could stick a bayonet into them,” one soldier wrote, “and not feel a thing.” But when the swelling went down, the pain was agonizing. If gangrene set in, the soldiers’ feet and legs were amputated. Conditions were so wet and filthy that even small sores became badly infected. Miserable conditions were only one part of the horror of trench warfare. Daytime at the front was dangerous. Front-line trenches were sometimes within 25 to 100 metres of enemy lines, and soldiers moved carefully with their heads down. A head above the trench line was an easy target for German sharpshooters. During five “quiet” months, one Canadian battalion lost a quarter of its men – nearly 200 were killed or wounded. Night time was worse. Men had to climb out of the trenches for patrols in noman’s land and to repair the parapets and string barbed wire. Night was also the time for surprise attacks. Raiding the parties would creep across no-man’s land, using wire cutters to cut their way through the barbed wire. Then they would descend on enemy troops with grenades and bayonets. Dawn was the worst time of all. It was the favored hour for major attacks and “going over the top” – climbing out of the trenches and charging across no-man’s land in an attempt to capture enemy trenches. The attacking troops were cut down by machine guns and artillery shells or tangled in barbed wire. Only a few made it to the enemy lines. Men who lay wounded in no-man’s land could not be rescued. Sometimes it took days before they died, and their companions could hear them crying out for help. The miseries and danger of trench warfare were too much for some soldiers, and they suffered nervous breakdowns. Victims of “shell shock”, or battle fatigue, they were unfit for fighting and sent away to asylums in England and Canada. Many never recovered. Some soldiers hoped for a “blighty” – a wound serious enough to cause the inured soldier to be sent back to England (blighty). At some time, almost every soldier must have wondered what he was doing at the front. YPRES The Canadian Division reached the Western Front in February 1915. Two months later, the Germans decided to unleash a new and terrible weapon – chlorine gas. They chose Ypres as the site for the first gas attack in history. The new Canadian troops had just joined French-Algerian troops in the trenches at Ypres. It was considered an honor to defend the last scrap of Belgian soil under Allied control. Their trenches were surrounded on three sides by German trenches. The Germans quietly carried 5730 cylinders of chlorine gas to the front lines and set them in place. In the early evening of April 22, they let off the chlorine gas. Allied High Command had been warned about a possible gas attack, but they failed to tell their soldiers on the front lines about it or to provide any instructions or means of defense. When the FrenchAlgerian troops saw the cloud of strange, green gas rolling towards them, they panicked and ran. The Germans then smashed through the gap left by the panicking troops. Soon a wall of deadly gas about three metres high began to drift over Canadian positions. Soldiers all over the battlefield gasped and cried as they breathed in the chlorine gas and began to suffocate. Word spread that soaking a handkerchief in urine and holding it up to one’s mouth would give some protection against the gas. Canadian troops held their positions three more days under repeated artillery and gas attacks until they were relieved by British reinforcements. A British soldier described what he had witnessed when he reached the front: “There were about 200 to 300 men lying in a ditch. Some were clawing at their throats. Their brass buttons were green. Their bodies were swelled. Some of them were still alive. Some were still writing on the ground, their tongues hanging out.” When the Canadian troops withdrew from the battlefield four days later, fewer than half the soldiers had survived. Although Canadian casualties totalled 6037, the Canadian “raw necks”, as inexperienced troops were called, had stood fast. The Canadians won high praise as courageous fighters. Their first major battle was a harsh lesson in the heroism and hardships of days to come. THE SOMME In 1916, the German army began pressing the French hard a Verdun. The British Commander-in-Chief, Douglas Haig, decided to go on the offensive and smash through the German lines in what came to be known as the Battle of the Somme. Haig was slow to adjust to the new demands of trench warfare. By the time he had adjusted, countless Allied lives were lost in a series of badly planned and poorly executed battles along the Somme. For five days before the Allied attack, the British and French bombarded the German lines with 1.5 million rounds of ammunition. Haig hoped that the shelling would wipe out the German front lines and break up the barbed wire defenses. The Germans, however, withdrew into trenches protected by massive concrete walls and nine-metrewide rolls of barbed wire until the bombardment ended. As a result, the German casualties were much lower than Haig had expected and the Germans’ barbed wire remained in place. Massive craters from the shelling made it hard for Allied infantry and cavalry units to charge the German line. The craters, however, were also ideal as machine-gun nests for German gunners. When Allied shelling stopped, the Germans know that an attack was coming. One hundred German machine guns were waiting to sweep the Allied attackers with a hail of bullets. The first battle in the Somme campaign began under a cloudless blue sky on July 1, 1916. A British officer scrambled out of the trenches and waved his troops forward. The men went over the top that day to meet the most ferocious artillery barrage they had ever faced. One German soldier described the fighting from a machine-gunner’s point of view. “When we started firing we just had to load and re-load. They went down in hundreds. You didn’t have to aim, we just fired into them.” That dreadful first day on the Somme did nothing to stop the Allied pursuit of victory. Haig insisted that the Somme campaign go forward, despite alarming casualty rates. During the next three months of fighting, the French and British lost more than 600,000 dead and wounded soldiers. The Canadians were spared until the attack on Fleurs-Courcelette on September 15, 1916. Two Canadian battalions – the FrenchCanadians of the 25th – captured the town of Courcelette and held it under repeated and savage German attack. “If hell is as bad as what I have seen at Courcelette, “ a FrenchCanadian colonel wrote in his diary, “I would not wish my worst enemy to go there.” Canadian troops fought battle after battle in the Somme campaign, including Fleurs-Courcelette, the Sugar Factory, Poziere Ridge, Fabeck Graben and Regina Trench. They gained most of their objectives but lost nearly 24,000 men. After 141 days, heavy winter rains forced Haig to call a halt. The Allied troops were utterly exhausted as were the Germans. A total of 1.25 million men had been killed or wounded during the fivemonth Battle of the Somme. After it was all over, the British army had advanced less than a dozen kilometres and the stalemate continued. By the end of 1916, the mood of Canadians both on the battlefield and on the home front had swung from hope to despair. It seemed as though the war might go on forever. Newfoundlanders at the Battle of the Somme The morning of July 1, 1916 is one the Newfoundlanders remember with pride and sadness. On this morning, the Newfoundland Regiment was sent across no-man’s land to face the deadly fire of German machine gunners. At the end of the day, 710 of the 800 Newfoundlanders who participated in the Battle of the Somme lay dead or wounded. They were only a few of the over 57,000 Canadians who fell during the battle many have described as the greatest military disaster in the history of the British Army. Before launching the attack, the British unleashed a heavy artillery barrage intended to knock out the German machine gunners and destroy the barbed wire. Unfortunately, neither of the objectives was achieved. When the first wave of English, Welsh and Scottish soldiers were sent across no-man’s land, it was broad daylight. It took only a few minutes for the German machine gunners to eliminate the entire first wave of soldiers from the battlefield. Upon hearing of the failure of the first wave to capture enemy territory, General Douglas Haig ordered the second wave, the Newfoundland Regiment, to go over the top. The soldiers, burdened with packs weighing from 30 to 75 kilograms, were instructed to walk across no-man’s land. The failure of the pre-attack bombardment to destroy the German barbed wire was to prove fatal. The Newfoundlanders, marching into a steady stream of machine-gun fire, were forced to funnel through a single gap in the barbed wire. This allowed the German machine gunners to train their sights on a single spot. In twenty-two minutes it was over; the Newfoundland Regiment was destroyed. One witness described the actions o the Newfoundlanders as “a splendid example of disciplined valor which failed because dead men can advance no further”. The memory of the brave soldiers who died on the battlefield of the Somme on that day has not been forgotten. To ensure that their memory would live on and that their bravery would be remembered, after the war the women of Newfoundland took up a collection and bought the land where their husbands, fathers, sons, and brothers fell. To this day, the land, still etched by the bomb craters and trenches of World War I, preserves the memory of those Newfoundlanders who fell during one of the bloodiest disasters of the war. THE BATTLE OF VIMY RIDGE In the brutal trench warfare of the Western Front, Canadian troops were steadily gaining a reputation as tough, effective and courageous fighters. The Battle of Vimy Ridge, a major turning point in the war, was the high point of Canadian military achievement in World War I. Vimy Ridge was a long, whale-shaped hump of land that rose 60 metres out of the Douai Plain. The ridge gave the Germans a commanding view of the British Army. It also protected a vital area of occupied France where mines and factories churned out supplies for Germany. Vimy Ridge was strategically important and had been strongly fortified. The Germans had dug a maze of deep trenches and dugouts and carved out huge underground chambers. Some of them were large enough to shelter whole German battalions from Allied barrages. The Germans had also built machine gun positions that were footed in thick concrete and wrapped in hedges of thick barbed wire. Although French and British troops had made several attempts to capture the heavily defended ridge, they had been stopped and turned back by German artillery. The German army was confident that nobody could force it off Vimy Ridge. The taking of Vimy Ridge now fell to the Canadian Corps under the command of the British General, Julian Byng. Under Byng’s command was Major-General Arthur Currie, the Canadian-born commander of the First Canadian Division. Currie once said, “Thorough preparation must lead to success. Neglect nothing.” Unlike earlier Allied attempts on Vimy Ridge, the Canadian assault left nothing to chance. Every stage of the attack was rehearsed to the last detail. Using aerial photographs taken by the Royal Flying Corps and information from intelligence raids across enemy lines, the Canadians pinpointed the locations of every trench, machine gun and battery. A full-scale mock-up of Vimy Ridge was built, and key positions were marked with flags and colored tape. Canadian troops practised every step they would take on the day of the attack. High in the air above the troops, Canadian pilots repelled German reconnaissance planes. Currie and Byng agreed that the strategy at the Somme had failed. When the artillery fire had stopped just before the assault, German troops had known what to expect. The advantage of a surprise attack had been lost. The new strategy was to keep up a “creeping barrage” during the assault that would lay a curtain of gunfire just in front of the advancing troops. The assault plan worked because of detailed planning and the courage and discipline of Canadian soldiers. By noon, the Canadians were looking down from Vimy Ridge at the grey backs of thousands of German soldiers in full retreat. The Vimy victory cost Canadians dearly. More than 3500 lives were lost. The German lines had been broken, however, and an important strategic position was now in Allied hands. Vimy showed the world that Canadians were capable of devising and carrying out a well-planned and successful attack. Currie was promoted to commander of the Canadian Corps in June 1917. It was no longer necessary for British officers to command Canadian soldiers. For the first time, Canada had its own officers in command of the Canadian Corps. THE BATTLE OF PASSCHENDALE Unfortunately, Vimy was not the last battle of the war. Against all advice, the British general, Douglas Haig, was determined to break through the German front. He launched a disastrous drive across Belgium in 1917, and in early October the Canadian Corps was ordered to prepare for the capture of Passchendale. It was the same front that Canada had defended in the Battle of Ypres. Four million shells had destroyed dams and drainage systems, and as a result, the battlefield was a nightmare of marshes and swamps. The Germans were on high ground above the battlefield. From their commanding position, they had the advancing Allied forces at their mercy. Currie reckoned that it would cost 16,000 Canadian lives to take Passchendale. He could not believe the military objective was worth the waste of lives, but Haig insisted on the offensive. Beginning in late October, the Canadians made a series of attacks. They crawled forward, often waist-deep in mud and under a deadly hail of German shells. At last they reached the outskirts of the ruined village of Passchendale and held on grimly for five days. By the time reinforcements finally came, the Canadians had been torn apart; only one-fifth of the attack force was still alive. When the fighting stopped on November 15, the British had gained just six kilometres and Canadian casualties stood at 15, 654. Despite the casualties, Canadian soldiers had performed admirably. Nine Canadian soldiers at Passchendale were awarded the Victoria Cross, the British Commonwealth’s highest military honor. THE LAST BATTLES In the spring of 1918, Germany decided to strike hard before the United States could enter the war. On March 21, German forces began a massive assault on the Western Front. Using new tactics based on mobility and surprise, the German army smashed through Allied defense and began to advance rapidly toward Paris. The German offensive nearly succeeded. The German army overran Allied forward positions and cut off Allied supply and communication lines. Using airplanes, trucks and mobile machine guns, they advanced within 70 kilometres of Paris. Although exhausted Allied troops reeled back and retreated under the massive assault, the Allied front did not collapse. Germany’s last desperate bid for victory had failed.