KOUGL, Jonathan H. Capstone Paper, Tribal Engagement in

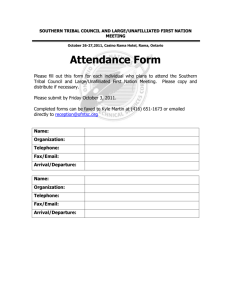

advertisement