1 Table of Contents Mission Statement

advertisement

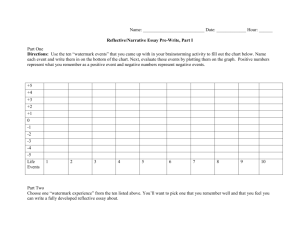

The Contemporary Situation Core One | Fall 2014 2 Table of Contents Mission Statement………….…………………….…………….…4 Course Understandings...………………….…………………...4 Collegial Agreements….………………………………………….5 Faculty……………………………….………………….……………..…5 Required texts…………….……………………….………………...6 Guest lecturers……………………………………….……………...6 Reflective essay handout…………………………………..……7 Reflective essay rubric…………………………..……..………..9 Argument handout……………………………………………….10 Argument rubric……………………………………..……….……12 Reading and lecture schedule………………….……………13 Best of Core contest winner.……………………..………….19 “Monster Masculinity” (supplemental reading)......26 3 Cover photo by “dhester,” made available by morguefile.com. 4 Mission Statement Core One begins the Core journey of self-discovery, encouraging students to engage in critical analysis of our world today. It helps students understand that individuals in contemporary society are interconnected, are impacted by the communities and cultures we live within. In examining the complexities of the contemporary world, the course emphasizes the Christian Humanist values of social justice, of treating human beings as individuals to be respected, rather than used as means to an end, and of recognizing that people can act as agents of change. Core One also begins a parallel journey of four years of skill development, offering students repeated opportunities to develop reading, writing, listening, and discussion skills. It asks students to write reflective and argumentative essays to explore the connections between the individual and the contemporary world. Key Understandings 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Students will understand that individuals in contemporary society are interconnected, are impacted by the communities and cultures we live within. Students will question the contemporary world’s challenges and opportunities from more than one perspective. Students will engage in respectful discussion to develop a deeper understanding of course material and diverse perspectives of that material. Students will write reflective and argumentative essays that respond to course material and are coherent, developed, and unified. Students will comprehend texts, that is, read to identify the purpose, genre, main ideas, and the evidence the author uses to support those main ideas. Content Understandings A. Students will understand that each individual is comprised of a complex mix of factors, including both biological and cultural factors. B. Students will understand that family values change throughout time and across cultures. C. Students will understand that human societies are man-made products, and as such, we have the power to change them. D. Students will understand that human societies establish systems that can cause the success or failure of its citizens. E. Students will understand that media images and advertising influence more than just our purchasing choices. F. Students will understand that the goods we buy at the store are the result of a global economic system, with far-reaching impacts. Further, they will understand that our purchases connect us to people all along those lines of production. G. Students will understand that technological developments change us, and that the pace of technological change today makes it crucial that we anticipate the direction we are headed. H. Students will understand that a certain disjunction exists because the human body and mind evolved over long periods of time to cope with the specific demands and opportunities of natural environments, but we most often today live in man-made environments rather than natural ones. 5 Collegial Agreements The Core One faculty agree to hold students accountable for reading, hearing, and viewing all course material by means of regular assessment, including tests with short answer or essay components. to create assignments that will allow us to determine how well students have met the course’s key understandings and content understandings. to encourage student participation and initiative in discussion sections and to note what students can do in discussion to help the class move toward a better understanding of course material. to require each student to deliver an oral presentation. to administer, during final exam week, a written exam with a comprehensive component. to assign and assess a minimum of 15-20 pages of formal writing, some of these pages requiring research. to offer students multiple opportunities to practice writing reflective and argumentative essays. to use a common rubric for the evaluation of these reflective and argumentative essays. to guide students in the use of Newsbank in writing assignments. to help students distinguish what Internet material is acceptable for use in writing assignments. to give students both formative (in-process) and summative (a final evaluation) feedback on their written work. to collect, for the purposes of formal assessment, final paper scores (out of 100 total points) for every student and for every paper given and graded with the common rubric (these will be reported without student names attached). Faculty Professor Sally Berger, WPUM radio station, 866-6211, sallyn@saintjoe.edu Professor Ashley Federer, office and phone TBA, afederer@saintjoe.edu Professor Tony Franco, Core 205, 866-6302, tfranco@saintjoe.edu Professor Elizabeth Gray, Computer Center, 866-6371, egray@saintjoe.edu Dr. Maia Hawthorne, Core 204, 866-6418, maia@saintjoe.edu Professor Kendra Illingworth, Office of Alumni and Parent Relations, McHale Hall, 866-6428, kendra@saintjoe.edu Professor Joe Koczan, Raleigh Hall 110, 866-6480, jkoczan@saintjoe.edu Professor Chris LaCross, Core 211, 866-6395, clacross@saintjoe.edu Dr. Jerry McKim, Core 251, 866-6438, jmckim@saintjoe.edu Professor James Nichols, Core 211, 866-6395, jnichols@saintjoe.edu Professor Heidi Rahe, Halleck Center 201, 866-6394, heidir@saintjoe.edu Dr. Rochelle Robertson, Core 233, 866-6376, rroberts@saintjoe.edu Dr. Tom Ryan, Core 249, 866-6232, tryan@saintjoe.edu Professor Courtney Stewart, Core 239, 866-6174, cstewart@saintjoe.edu Dr. Bill White, Core 202, 866-6236, billw@saintjoe.edu Professor Bonnie Zimmer, Core 260, 866-6379, bonniez@saintjoe.edu 6 Required texts The following books are required for the course. Anderson, M. T. Feed. Cambridge, MA: Candlewick Press, 2002. Print. ISBN: 978-0763622596. Core One Coursepack. Saint Joseph’s College. 2014. Print. (Available at the SJC College Store.) Eggers, Dave. Zeitoun. New York: Vintage, 2009. Print. ISBN: 978-0307387943. Graff, Gerald, and Cathy Birkenstein. They Say, I Say: The Moves That Matter in Academic Writing. New York: Norton, 2006. Print. ISBN: 978-0393933611. Moore, Wes. The Other Wes Moore: One Name, Two Fates. New York: Spiegel & Grau, 2011. Print. ISBN: 9780385528207. Schlosser, Eric. Fast Food Nation: The Dark Side of the All-American Meal. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2001. Print. ISBN: 978-0547750330. Walls, Jeannette. The Glass Castle: A Memoir. New York: Scribner, 2005. Print. ISBN: 978-0743247542. Guest lecturers Dr. Bob Brodman, Biology Professor Susan Chattin, History Dr. Michael Nichols, Philosophy and World Religions Dr. Chad Pulver, Psychology Dr. Mark Seely, Psychology Dr. Michael Steinhour, Sociology Dr. Lana Zimmer, Education Dr. Suzanne Zurn-Birkhimer, Mathematics 7 The Reflective Essay In Core One you’ll be writing two kinds of essays: the argument and the reflective essay. It is likely that you already have a sense of what an “argument” is. But what is a reflective essay? Our idea of the reflective essay is inspired by Michel de Montaigne, the sixteenth-century French writer who invented the essay form by writing short, subjective pieces on various topics of importance in his day, such as religious controversy, the colonization of the New World, and the institution of marriage. This semester, we will ask you to write short, subjective pieces that consider questions relevant to our Core One subject matter. The following are the criteria we have in mind for reflective essays. 1. Reflective essays are driven by questions. These essays should develop out of questions that you have, questions that are open-ended, rather than questions that have definite answers. In your Core One essays, the questions you consider should be ones that arise out of the subject matter of the course. Here are some examples of questions that arise out of the reading and lecture material: “What does The Glass Castle tell us about parenting?” “How was I parented and was it beneficial?” “Has the place that I’m from marked me in some way?” “What makes some people successful and others not?” “Are cities preferable to small towns?” “Are we too reliant on the Internet?” “How does marketing shape my behavior?” “What’s the proper relationship between man and nature?” “Are local economies preferable to global ones?” You’ll note that these questions fall into several different categories: (1) questions specifically about the books or characters (2) questions about your life that are inspired by the books/lectures (3) questions about our world that are inspired by the books/lectures Each kind of question is acceptable. And depending upon which kind of question you are answering, you might recognize that your essay begins to share characteristics in common with other genres: literary analysis, memoir, report. What sets them apart from these other genres is what follows on this list of characteristics. About the above list of questions: as you read, listen, and discuss this semester, you’ll be able to add your own questions to the list. Be alert for open-ended questions that arise for you as you read. These could become springboards for some great reflective essays. 2. Reflective essays are unified. Each essay should consider one primary question rather than a string of questions. It is a cohesive piece of writing that has a clear focus. 3. Reflective essays are subjective. They represent your thinking about the subject matter, rather than a report on someone else’s thinking. They open your mind up to readers. 4. Reflective essays are speculative in tone. In writing, “tone” refers to one’s attitude toward the subject matter. In a comic essay, for example, you might adopt a sarcastic tone. In an argument, your tone might be firm, insistent. Given that your task in the reflective essay is to consider a question, you should adopt a thoughtful, reflective, speculative tone. 5. The body of reflective essays simply consider the question at hand. This criteria is one way that these essays differ from arguments. In a written argument, you’ve already come to a conclusion and you’re trying to persuade others that your conclusion is the right one. A reflective essay allows room for thought on a question about which you don’t necessarily have a solid answer. So the point of 8 reflective essay is to try to work through the question, acknowledging its challenges. Difficult questions require time and space to organize and make sense of your thoughts. That’s what this genre allows for. 6. Reflective essays are thoughtful. That means they aren’t superficial--they really think something through. If you find yourself stuck as you generate material for your essay, see whether the following questions help prompt more ideas. ● Consider your connection. What’s been your experience with this issue? How might that experience compare with others’? ● Consider its various parts. Take apart the issue at hand. Is one part of it clear, but another one murky? ● Consider it from various points of view. Who are all the parties affected by this issue? How might the issue look to them? ● Consider its context. How do the circumstances in which this issue arises come to bear upon it? ● Consider relevance. Why is this issue important? 7. Reflective essays are written with an external audience in mind. Given what we have said above, you might be tempted to think of the reflective essay as “private writing,” writing intended only for you. Not so! The kinds of questions you’ll be considering in these essays are the kinds of questions that are interesting to a wide audience. Print and online magazines are filled with essays on Core One-type questions, because these questions are pertinent to human lives today. The Core One faculty expect that all the essays you write for Core One be written for an audience broader than just yourself. That means these essays are formal writing, just as the arguments are. For more specific information about whom you should have in mind as you write, see your instructor. 8. Reflective essays include relevant supporting details. As with any essay, you need to paint a vivid picture for your audience. Dramatize what you’re talking about! Make your points clear with anecdotes, examples, hypothetical situations, narratives, descriptions. Use all the tricks that good writers use to show your readers what you’re talking about. 9. The organization of reflective essays grows out of their content. You might find yourself needing to be more attentive to organization in reflective essays than in arguments because you’re spinning out trains of thought rather than supporting a thesis. As you decide how to organize the material you’ve generated in early drafting, consider the following to help you organize your ideas. ● Be thorough. Work through one idea completely before moving on to the next one. You know what you’re talking about, but your audience might not! Keep that audience in mind as you explain yourself. ● Be methodical. Move logically from one idea to the next. Again, keep the audience in mind. What would make the most sense for your reader? ● Provide transitions. Help baby-step your reader from one idea to the next by explaining explicitly the connections between ideas. 10. The conclusions of reflective essays are honest assessments of where your thinking stands. If you work through the question at hand and feel you feel that you have come to some sort of resolution, great. But if you feel only tentative about the conclusions you’ve reached, explain that. What do you know for certain and what is there left to discover? If there are aspects of the question that still elude you, for instance, acknowledge them. If your thinking has led you to another question that needs further research before you can move ahead, explain that. Honestly assess what you can feel confident about concluding and what you cannot. Your instructor will provide you examples of reflective essays. Look for the above criteria in those essays. Ask your instructor any questions you might have about what qualifies as a reflective essay. 9 Reflective Essay Rubric | Core One | Fall 2014 Category Excellent Content 50% Organization 20% Writing Style and Conventions 30% Acceptable Unacceptable 45-50 points Expertly responds to the assignment Expertly explores an open-ended courserelated question Focuses on one particular subject Develops subject thoroughly, thoughtfully Includes relevant supporting evidence or details Employs adept logical thinking Arrives at a highly satisfactory conclusion Sources (if any) are appropriate Sources (if any) are mined for useful information and incorporated skillfully in the content Successfully addresses the appropriate audience 35-44 points Generally responds to the assignment Explores an open-ended, course-related question Tends to focus on one particular subject Tends to develop subject Tends to include relevant supporting details Tends to employ sound logical thinking Arrives at a satisfactory conclusion Sources (if any) tend to be appropriate Sources (if any) mostly mined for useful information and competently incorporated in the paper Tends to address appropriate audience <35 points Does not respond to the assignment Does not explore an open-ended, courserelated question Does not focus on one particular subject Undeveloped Tends not to include relevant supporting details Logic tends to be faulty Does not arrive at a satisfactory conclusion Sources (if any) tend not to be appropriate Sources (if any) not mined for useful information, awkwardly incorporated in the paper Tends not to address appropriate audience 18-20 points Employs an appropriate organizational strategy Presents material in a logical order Includes a variety of appropriate paragraph to paragraph and sentence to sentence transitions which help the reader move from one idea to the next 14-17 points Has an organizational strategy, but it may not be the one best suited to the material or it may be employed somewhat inconsistently Seemingly presents some material out of logical order, but not enough to distract the reader from the essay’s overall message Includes paragraph to paragraph and sentence to sentence transitions that are mostly successful <14 points Does not seem to employ an organizational strategy Seemingly presents some material well enough out of logical order that it distracts the reader from the essay’s overall message Does not offer transitions that assist reader paragraph to paragraph and sentence to sentence 27-30 points Tone of the piece is questioning, speculative, curious Strong sense of the author’s voice Precise, vivid, and striking vocabulary and phrases Variety of grammatical structures that seem carefully chosen for their rhetorical effect Sentences are clear and graceful Sources (if any) correctly documented in the citation style required by the instructor Very few, minor deviations from Standard Written English (SWE) Page formatting matches assignment 21-26 points Tone mostly questioning, speculative, curious Author’s voice beginning to emerge Precise vocabulary and phrases Some variety of grammatical structure Sentences are clear Sources (if any) documented properly for the most part Some deviations from Standard Written English (SWE), but deviations that tend not to distract readers from content Page formatting matches assignment for the most part <21 points Tone not questioning, speculative, curious Little sense of the author’s voice Somewhat limited or otherwise problematic vocabulary and phrases Repetitive or non-grammatical structures Problems with clarity Sources (if any) not properly documented Deviations from Standard Written English (SWE) distract readers from content Page formatting deviates from assignment a great deal, distracts reader from content 10 Comments The Argument One genre of writing you’ll be working on this semester is the argument. By “argument” we don’t mean a fight. We don’t have in mind an essay that is hostile or combative. What we do have in mind is the most common kind of academic writing you’ll find that you’ll do while in college and beyond: writing in which you take a reasoned position on a debatable issue and attempt to persuade your readers that your position is the best one. The following are the criteria we have in mind for arguments. 1. An argument is driven by a thesis statement. A thesis statement is a simple, clear statement of your position. It is often just one sentence. Though there is such a thing as in inductive argument essay, in which the thesis statement comes at the end, you’ll likely be asked more often to write with a deductive format, in which the thesis is presented at the outset of the essay. The deductive format, with the thesis statement located at the beginning of the essay, is the kind of argument we’ll ask you to concentrate on this semester. The following are examples of thesis statements that might arise out of the content in the first unit of the course: Rex Walls is an irresponsible parent. The Walls family’s problems might, on the surface, seem problems of poverty, but they are really problems of alcoholism. The members of the Walls family are, to some degree, products of the places they’ve lived. While parenting styles are shaped by culture, and therefore relative, parenting styles are simply not equal. Some cultures encourage parenting styles that are more humane than others. Americans hold on to outdated notions of family because cultural attitudes take longer to change than do the material conditions of our lives. Media presents a distorted view of the American family. You’ll note that these thesis statements fall into a couple of different categories: (1) positions taken about the content or characters of one of our readings (2) positions taken about the world we live in In an essay with the first kind of thesis statement, you’d be drawing upon evidence from the book to support your position. In an essay with the second kind of thesis statement, you’d be drawing upon evidence of other kinds: your own observation, lecture content, news accounts, studies, published academic arguments. Your instructor’s assignment prompt will guide you in terms of what kind of thesis statements you’ll be writing this semester. 2. An argument is unified. Each argument you write this semester will argue one position. The whole essay should stay focused on supporting that one position. 3. An argument is about a debatable subject. If the issue at hand is not debatable, why bother? You can’t make an argument out of an opinion, for instance. “I love Jeannette Walls’s depiction of her siblings” is not a good thesis statement because no one can really argue with you about it! You also can’t make an argument out of a fact. “Jeannette Walls wrote The Glass Castle to come to terms with her origins, which she was having a hard time reconciling with her adult life.” Walls tells us as much in interviews, so a paper that explores this is more a report than an argument. As you try to arrive at a thesis statement that will result in a strong, exciting paper, consider whether your thesis statements could be stronger by moving away from “less debatable” positions toward “more debatable” positions. “Rose Mary Walls often makes choices that are difficult to understand” is an okay place to start, but is perhaps closer to a statement of fact than a true, arguable thesis. Consider how much stronger a paper would be with this thesis statement: “While Rose Mary Walls’s actions can confuse and frustrate readers, a close reading of the book suggests that her parenting behaviors are a response to her husband’s alcoholism.” That’s mapping out a position! 11 4. An argument explains the context. Arguments don’t happen in a vacuum; they are part of a larger conversation. They respond to things that other people have said, or might say, about your topic. The book we’re using as an aid in our writing class, They Say / I Say, will put it like this: “[I]n the real world, we don’t make arguments without being provoked. Instead , we make arguments because someone has said or done something (or perhaps not said or done something) and we need to respond.” (3) Your arguments should include that context! What are others saying, not saying, or likely to say about your topic? Include that in your essay! Arguments also often require some background information to make sense. If you’re arguing that Americans hold onto outdated notions of family, you need to explain a bit about the history of the American family for that to make sense. What did those families once look like? What do they look like now? What attitudes about family do American express when they are asked? Only once readers have that context will your argument make sense. 5. An argument is based on good reasons. A position alone is not enough in a written argument: you need also to show the reader you have sound reasons for holding your position. What has brought to your position? Spell those reasons out methodically for the reader. 6. An argument uses evidence to support those reasons. As noted above, the kinds of evidence you use will be different depending upon the kind of argument you’re writing. These could include examples from a text, your own observation, lecture content, news accounts, statistics, studies, or published academic arguments. Discuss with your instructor what kinds of evidence might make the most sense given your thesis. 7. An argument is persuasive. To be persuasive, you have to consider your audience. Who are they? What would they find persuasive? Appeal to their knowledge base and their values. If you’re not clear about who the audience is for your paper, ask your instructor. 8. An argument employs an appropriate tone and voice. Readers need to trust and respect a writer to accept her argument. Something to consider as you write, then, is how to create a honest, trustworthy voice. “Voice” refers to the persona the reader “hears” as he reads. Voice comes from a number of elements of the writing, like how the sentences are put together, word choice, and tone. “Tone” refers to the writer’s attitude about the content of a written piece. The writer of a comic essay, for instance, might adopt a sarcastic tone. The tone of an argument could be firm, insistent, even urgent, or it could be cool, reflective, thoughtful. As you write, think about what kind of voice and tone to which your audience would be most receptive and how you might convey that voice and tone in the written word. Look at model arguments to help you think about how voice and tone are created by words. 9. An argument considers the opposition. They Say / I Say calls this “Planting a Naysayer in Your Text.” If your position is truly debatable, that means that others hold other points of view. What are those positions those folks hold? Where do their arguments have merit? Why do you disagree? Your own argument will become much clearer and stronger if you work through where and why your position meets and diverges from others’. They Say / I Say has much to offer on this subject, and we’ll be using it this semester to figure out how to enhance your own argument by drawing in the opposition. Your instructor will provide you examples of arguments. Look for the above criteria in those essays. Ask your instructor any questions you might have about what qualifies as an argument. 12 Argument Rubric | Core One | Fall 2014 Category Excellent Content 50% Organization 20% Writing Style and Conventions 30% Acceptable Unacceptable 45-50 points Expertly responds to the assignment Purpose is clear Takes a clear and debatable position Offers appropriate background information Offers sound reasons Uses well-researched, appropriate, convincing evidence Carefully considers alternate positions Employs adept logical thinking Includes only relevant information Sources (if any) are appropriate Sources (if any) are mined for useful information and incorporated skillfully in the content Successfully addresses the appropriate audience 35-44 points Generally responds to the assignment Purpose tends to be clear Takes a debatable position that is clear for the most part Tends to offer appropriate background information Tends to offer sound reasons Tends to use well-researched, appropriate, convincing evidence Tends to consider alternate positions Employs sound logical thinking Tends to includes only relevant information. Sources (if any) tend to be appropriate Sources (if any) mostly mined for useful information and competently incorporated in the paper Tends to successfully address appropriate audience <35 points Does not respond to the assignment Purpose tends not to be clear Position unclear Tends to neglect necessary background information Reasons weak or unclear Weak or scanty evidence Does not consider alternate positions Logic faulty Tends to include irrelevant information Sources (if any) tend not to be appropriate Sources (if any) not mined for useful information, awkwardly incorporated in the paper Unsuccessful in its attempts to speak to its audience or appeals to the wrong audience 18-20 points Employs an appropriate organizational strategy Thesis presented at the outset Presents material in a logical order Includes a variety of appropriate paragraph to paragraph and sentence to sentence transitions which help the reader move from one idea to the next 14-17 points Organizational strategy may not be the one best suited to the material or it may be employed somewhat inconsistently Thesis presented at the outset Some material out of logical order, but not enough to distract the reader from overall message Mostly successful transitions between paragraphs, sentences <14 points Does not seem to employ an organizational strategy Thesis not presented at the outset Some material well enough out of logical order that it distracts the reader from the essay’s overall message Lacks transitions between paragraphs, sentences 27-30 points Voice and tone of the piece are appropriate for the subject matter Precise, vivid, and striking vocabulary and phrases Variety of grammatical structures that seem carefully chosen for their rhetorical effect Sentences are clear and graceful. Sources (if any) correctly documented in the citation style required by the instructor Very few minor deviations from Standard Written English (SWE) Page formatting matches assignment 21-26 points Voice and tone of the piece tend to be appropriate for the subject matter Precise vocabulary and phrases Some variety of grammatical structure Sentences are clear Sources (if any) documented properly for the most part Some deviations from Standard Written English (SWE); tend not to distract readers from content Page formatting matches assignment for the most part <21 points Voice and tone tend not to be appropriate Somewhat limited or otherwise problematic vocabulary and phrases Repetitive or non-grammatical structures Problems with clarity Sources (if any) not properly documented Deviations from Standard Written English (SWE) distract readers from content Page formatting deviates from assignment a great deal, distracts reader 13 Comments Core One: The Contemporary Situation Reading and Lecture Schedule 2014 Core One asks students to think critically about our contemporary world and culture. It also begins the Core journey of selfdiscovery. The course is organized around a number of topics and essential questions related to those topics: FAMILY VALUES, CULTURAL VALUES: How do family and culture play a role in making us who we are? What kinds of family values and cultural values are we seeing in our country today? AMERICA UNDER PRESSURE: From industrialization and globalization to threats to national security, how have these challenges impacted us? How well are we holding up under the pressure? A LOOK AHEAD: What does the future hold for us? What do we want our future to look like? As students and faculty read books that ask these questions, they will also hear from experts across academic disciplines and professions about what their discipline or profession brings to the question at hand. Students should leave this course with an appreciation of the complexities of these issues and with experience charting the intersection of these issues with their own lives. Week Day Reading Lecture Tuesday 8/19 One Introduction No reading Dr. Maia Hawthorne, English, “Welcome to Core” In this lecture Dr. Hawthorne, Director of Core One, will welcome students to liberal arts education at Saint Joseph’s College—the Core program—and to Core One in particular, outlining expectations for the course. Dr. Hawthorne will also ask students to begin considering the question of what’s “contemporary” about the contemporary situation and what that might mean in our lives. Writing No reading -- Thursday 8/21 The Glass Castle, pages 1-57 (57 pages) Dr. Maia Hawthorne, English, “Memory and Meaning-Making: The Memoir” The Glass Castle is a memoir. What does that mean? Who reads memoirs and why? Why are we reading memoir in Core One? Why do people write memoirs? What’s the relationship between memoir and the “reflective essay” that’s a required part of the writing program in Core? The Glass Castle, pages 58-115 (57 pages) Dr. Tom Ryan, Education, “The Glass Castle and The Reflective Essay: Using the Readings To Explore the Meanings inside One's Experiences” Dr. Ryan will build on Thursday’s lecture to demonstrate how The Glass Castle might be used as a springboard for your own work. “The Reflective Essay.” This handout is included in the coursepack. Model reflective essays will be provided by your instructor. (2 pages) -- Writing Two Tuesday 8/26 One FAMILY VALUES, CULTURAL VALUES: How do family and culture play a role in making us who we are? What kinds of family values and cultural values are we seeing in our country today? 14 Thursday 8/28 Tuesday 9/2 The Glass Castle, pages 175-234 (59 pages) Professor Susan Chattin, History, “The American Family: A Historical Perspective” The Glass Castle helps us think about the relationships between individuals and their families, but how typical is the family in this memoir? What have American families looked like historically? What do they look like today? What can that tell us about who we are? Writing No reading (or reading assigned by your instructor) -- Thursday 9/4 The Glass Castle, pages 235-288 (53 pages) Dr. Chad Pulver, Psychology, “You’re Just Wired That Way” As a counter to the idea that “who we are” comes from how we were parented and where we grew up, this lecture will look at the biological, genetic impact on behavior, decision making, and personality. Tuesday 9/9 “Monster Masculinity: Honey I’ll Be in the Garage Reasserting My Manhood” by Peter Tragos. This article can be found in the coursepack. (14 pages) Missrepresentation, 45 minutes of a 90 minute film To what extent do the values of corporate America impact us beyond our purchasing choices? This documentary considers that question, focusing specifically on images of women in advertising. -- Writing “The Argument.” This handout is included in the coursepack. Also, “Sports: It’s Just a Name,” model argument found in the coursepack. (8 pages) The Other Wes Moore, Part One (62 pages) Michael Steinhour, Sociology, “Black American Families” What light can recent sociological studies of black American families shed on the families of The Other Wes Moore? The Other Wes Moore, Part Two (66 pages) Video lecture by Michelle Alexander on her book The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, introduced by Dr. Rochelle Robertson, Communication. The New Jim Crow argues that we have not ended a racial caste system in this country. Alexander suggests that by targeting black men through the War on Drugs and labeling them felons, it is possible to discriminate in many of the same ways our country did historically—through housing, employment, education, and public benefits. It could be argued that this is the system that shapes the lives of the two Weses. Writing They Say, I Say, preface and introduction (26 pages) -- The Other Wes Moore, Part Three, Epilogue, Afterword, and A Call to Action (66 pages) Dr. Jerry McKim, Education, “The Opportunities Afforded by Our Nation’s Schools” The Other Wes Moore ends by asking us to seriously consider the options we, as a nation, present to or withhold from our children. This lecture will consider education as a part of that equation. Five Tuesday 9/16 Thursday 9/11 Dr. Michael Nichols, Philosophy and Religion, “Cultural Perspectives on Parenting” This lecture asks questions about how parenting influences children and how culture influences parenting. What assumptions are made in different cultures about parenting and the role of parents in helping children develop? Is there such a thing as a "right way" to raise children? Thursday 9/18 Three Four The Glass Castle, pages 116-174 (58 pages) 15 Tuesday 9/23 Six Test day, no reading Test day, no lecture Thursday 9/25 -- Fast Food Nation: Introduction Chapter 2: Your Trusted Friends (38 pages) Guest lecturer, Dr. Lana Zimmer, Education, “The Industrial Food Complex” Fast Food Nation is an example of investigative journalism, a journalist’s deep investigation into a particular topic, in this case, fast food. Food author Michael Pollan has said that we live in an age in which we need investigative journalism to unveil the origin of the food we buy, not just in fast food establishments, but in supermarkets as well. How can that be true, and what does it mean for us? What are some of the ways that communities across the nation have responded to this state of affairs and what’s being done locally to that end? Fast Food Nation: Chapter 3: Behind the Counter Tony Franco, Business Administration, “The Battle Over Minimum Wage” Fast Food Nation gives us a glimpse of the working lives of those people who work behind the fast food counter, the very population who have been in the news a great deal over the last couple of years as they have fought for higher wages. Who tends to work behind fast food counters today? What is their argument for higher wages, and the broader argument to raise minimum wage, about? Writing -- Fast Food Nation: Chapter 7: Cogs in the Great Machine Chapter 8: The Most Dangerous Job (37 pages) Dr. Bill White, History, “Is America a Great Place to Work?” We will begin by reviewing the various pressures on meat packing executives and the people who work in their factories as described in Fast Food Nation. Then we'll examine how work has been organized in America from 19th stores to a 2014 McDonald's. Students will better understand fights over who controls the workplace. Fast Food Nation: Chapter 9: What’s in the Meat (29 pages) Dr. Bob Brodman, Biology, “How Can We Make Sure Our Food Is Safe to Eat?” To best serve their economic interests the fast food industry has devised food processing methods to increase the uniformity of their products and has lobbied to reduce expensive government regulations. Consumers like that because it keep prices low and quality consistent. But how safe is food processed this way? How does it affect nutrition and put us at risk of food poisoning? Has this process affected worker safety? Have things gotten better in the 10 years since Fast Food Nation was written? What can you do to ensure that your food is safe to eat? No reading (or reading assigned by your instructor) -- Fast Food Nation: Chapter 10: Global Realization (27 pages) Dr. Bill White, History, “A Post-American World” A quick synopsis of the debate over globalization will introduce a film that examines WalMart’s pricing and purchasing practices. Students should understand that the goods we buy are often the result of global decisions that have effects upon workers in the United States and abroad. Tuesday 10/7 No reading (or reading assigned by your instructor) Thursday 10/2 (30 pages) Writing Eight They Say, I Say, part one (33 pages) Thursday 10/9 Seven Tuesday 9/30 Six Writing AMERICA UNDER PRESSURE: From industrialization and globalization to threats to national security, how have these challenges impacted us? How well are we holding up under the pressure? 16 Tuesday 10/14 Writing No reading (or reading assigned by your instructor) -- Thursday 10/16 Zeitoun, pages 1-68 (Friday, August 26 through Saturday, August 27) (68 pages) Guest lecturer, Dr. Suzanne Zurn-Birkhimer, Mathematics, “Living in the Age of Extreme Weather” Zeitoun takes place during Hurricane Katrina, the devastating storm that ravaged New Orleans in September 2005. Katrina is one example of the increased severity of storms around our planet today. Why is this extreme weather happening? Is extreme weather the new normal? How should we respond? Tuesday 10/21 Zeitoun, pages 68-127 (Sunday, August 28 through Thursday, September 1) (59 pages) “Act I” of When the Levees Broke, a documentary film by Spike Lee What did New Orleans look like and feel like as the storm approached and hit? Through a mix of footage of New Orleans, media clips, and interviews, this documentary helps us see and feel what the residents of New Orleans were experiencing in the days leading up to and after the storm. Writing They Say, I Say, part two (50 pages) -- Zeitoun, pages 127-191 (Friday, September 2 through Tuesday, September 13) (64 pages) Joseph Koczan, Core, “The Breaching of the Levee and the Fault Lines of Race and Class in New Orleans” During the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, some Americans suggested that the inadequate government response was due in part a manifestation of its racism and classism, given that many of the storm’s victims were black and poor. This story about race and class in the aftermath of Katrina speaks in interesting ways to Zeitoun’s own experience of being a Syrian-American in a post-9/11 America under pressure. How did Katrina expose our nation’s race anxiety? Tuesday 10/28 Zeitoun, pages 191-256 (Wednesday, September 14, Kathy’s perspective, through Wednesday, September 14, Abdulrahman’s perspective) (65 pages) PBS Frontline special “The Storm” What do we expect of our government during threats to our security? How well did the government respond during Katrina? This 60 minute program was broadcast six months after Hurricane Katrina and analyzes the government response to the event. They Say, I Say, part three (56 pages; a lot of reading, but note that the last 15 of these pages are a sample student essay) -- Zeitoun, pages 256-325 (Thursday, September 15-end) (69 pages) The Core One Colloquium, featuring the work of current Core One students The Core One colloquium gives you, the students, an opportunity to have your voices join those of our Core One lecturers and authors and to share your perspectives with an audience wider than your own professor or discussion section. It gives those of us in attendance an opportunity to see what others have been thinking about Core One subject matter or the ways in which the course’s subject matter has served as a springboard into personal reflection. Details about how the colloquium works are forthcoming. Thursday 10/30 Eleven Thursday 10/23 Inequality for All, 45 minutes of a 90 minute film In 2013, President Obama called economic inequality “the defining issue of our time.” This documentary by political economist and commentator Robert Reich explores the history of economic inequality and the reasons for it. Writing Nine Ten Online reading from: The full transcript of President Obama’s December 4, 2013, remarks on the economy, available at www.washingtonpost.com. 17 Tuesday 11/4 Twelve Test day, no reading Test day, no lecture Writing No reading (or reading assigned by your instructor) Thursday 11/6 Growing up Online, PBS Frontline video watched outside of class, available online at http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/fr ontline/kidsonline/ Sally Berger, Digital Media and Journalism, “Our Relationship with Social Media” This lecture will explore the ways that social media changes the way we live and think. Tuesday 11/11 Feed, pages 1-72 (72 pages) Dr. Maia Hawthorne, English, “Science Fiction” This lecture will introduce the book Feed by considering the following questions: how is science fiction used to explore what it means to be human? How is Feed an example? What are the questions recent science fiction has considered? What are the questions Feed is considering? Writing No reading (or reading assigned by your instructor) -- -- Tuesday 11/18 Professor Bonnie Zimmer, Art, “21st Century Artists Respond to Their World: Exploring Our Relationship with Nature” Alexis Rockman and Chris Jordan are two artists whose work meditates on the relationship between man and nature. Professor Zimmer will introduce us to the work of these artists, suggesting ways that it comments on our recent discussions about man and our planet. Feed, pages 151-226 (75 pages) Writing Courtney Stewart, Philosophy, “Digital Reading, Digital Thinking, and Ethics” This lecture will investigate how the brain works at a biological and neurological level, contending that our online lives have fundamentally changed the organization of our brains. It will consider the differences between the “old,” linearly-organized brain, and the “new,” non-linearly organized brain. In addition, this lecture will consider what biological, personal, and social outcomes may result from continuous interaction with and increased dependence upon technology and explore the ethical implications of this trend. No reading (or reading assigned by your instructor) -- Thursday 11/20 Feed, pages 73-150 (77 pages) Feed, pages 227-300 (73 pages) Professor Jon Nichols, Composition and Rhetoric, “Transhumanism as Science Fact “ Transhumanism is the idea of using technology to enhance a person's body and mind. We see numerous examples of this in Feed. Prof. Nichols will take a look at these aspects of the book as well as other examples from science fiction and connect them to real world, cutting-edge technology. Feed may not be so fictional after all. 11/25 & 11/27 Break Fourteen Thursday 11/13 Thirteen Twelve A LOOK AHEAD: What does the future hold for us? What do we want our future to look like? Thanksgiving Break Enjoy your holiday! 18 Tuesday 12/2 Dr. Mark Seely, Psychology, “A Touch of Nature” Human bodies and minds are designed by evolution to cope with the specific demands and opportunities of natural environments. Despite this, most of us spend the greater portion of our lives in human-constructed environments, largely isolated from the natural world. Wild nature is typically treated either as an alien and inhospitable place or as a kind of “spice” to be added here and there in tiny, controlled doses (pets, houseplants, weekend camping trips). This lecture will use research findings from the field of evolutionary psychology to explore some of the ways that our physical and psychological wellbeing are affected by exposure—and lack of exposure—to the natural world. No reading (or reading assigned by your instructor) -- No reading Dr. Maia Hawthorne, English, “What Does the Future Hold for You?” This lecture will use the essential questions of the final unit to ask us to think about the meaning of the overall project of Core One and what it has helped us accomplish. It will address the question “Tell me again--why are we doing this ‘Core’ thing?” Consult the exam schedule and your professor for the time of your section’s exam. Hope you enjoyed Core One. Good luck to you on your exams! 12/8-11 Exam week Thursday 12/4 Writing Fifteen Online reading: “A Walk in the Woods: Right or Privilege?” by Richard Louv (March/April 2009). Available at www.orionmagazine.org. 19