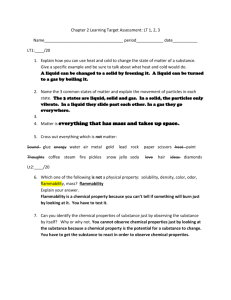

SECTION 3-------

advertisement