Social Isolation Research Report

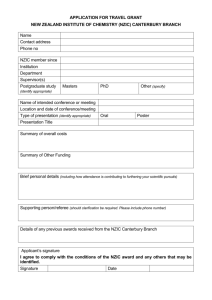

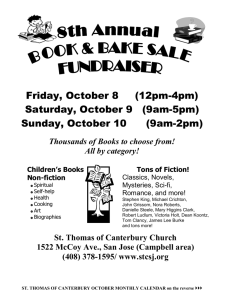

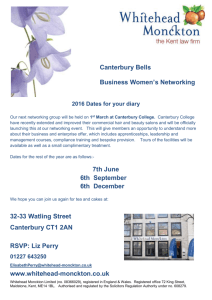

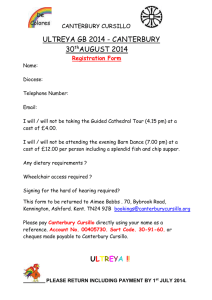

advertisement