A Passage of Loss - UROP 复旦大学本科生学术研究资助计划

advertisement

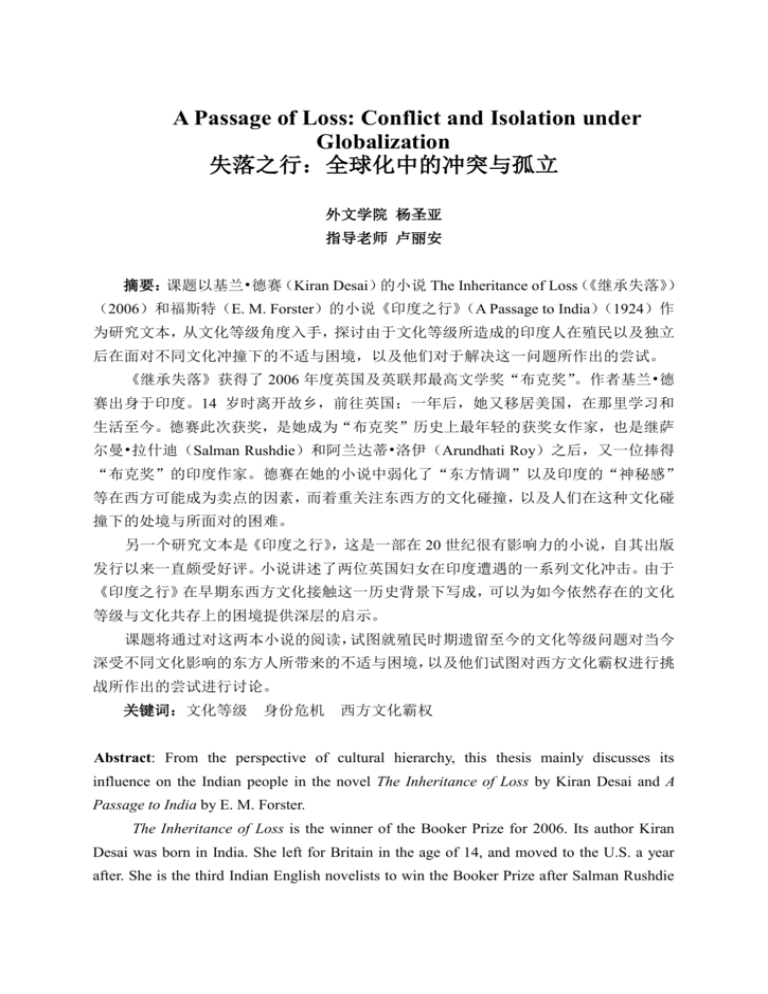

A Passage of Loss: Conflict and Isolation under Globalization 失落之行:全球化中的冲突与孤立 外文学院 杨圣亚 指导老师 卢丽安 摘要:课题以基兰•德赛(Kiran Desai)的小说 The Inheritance of Loss(《继承失落》) (2006)和福斯特(E. M. Forster)的小说《印度之行》 (A Passage to India) (1924)作 为研究文本,从文化等级角度入手,探讨由于文化等级所造成的印度人在殖民以及独立 后在面对不同文化冲撞下的不适与困境,以及他们对于解决这一问题所作出的尝试。 《继承失落》获得了 2006 年度英国及英联邦最高文学奖“布克奖”。作者基兰•德 赛出身于印度。14 岁时离开故乡,前往英国;一年后,她又移居美国,在那里学习和 生活至今。德赛此次获奖,是她成为“布克奖”历史上最年轻的获奖女作家,也是继萨 尔曼•拉什迪(Salman Rushdie)和阿兰达蒂•洛伊(Arundhati Roy)之后,又一位捧得 “布克奖”的印度作家。德赛在她的小说中弱化了“东方情调”以及印度的“神秘感” 等在西方可能成为卖点的因素,而着重关注东西方的文化碰撞,以及人们在这种文化碰 撞下的处境与所面对的困难。 另一个研究文本是《印度之行》,这是一部在 20 世纪很有影响力的小说,自其出版 发行以来一直颇受好评。小说讲述了两位英国妇女在印度遭遇的一系列文化冲击。由于 《印度之行》在早期东西方文化接触这一历史背景下写成,可以为如今依然存在的文化 等级与文化共存上的困境提供深层的启示。 课题将通过对这两本小说的阅读,试图就殖民时期遗留至今的文化等级问题对当今 深受不同文化影响的东方人所带来的不适与困境,以及他们试图对西方文化霸权进行挑 战所作出的尝试进行讨论。 关键词:文化等级 身份危机 西方文化霸权 Abstract: From the perspective of cultural hierarchy, this thesis mainly discusses its influence on the Indian people in the novel The Inheritance of Loss by Kiran Desai and A Passage to India by E. M. Forster. The Inheritance of Loss is the winner of the Booker Prize for 2006. Its author Kiran Desai was born in India. She left for Britain in the age of 14, and moved to the U.S. a year after. She is the third Indian English novelists to win the Booker Prize after Salman Rushdie and Arundhati Roy, and she is youngest woman winner. Her novel focuses on an Indian family in the 1980s and their struggle between two cultures. A Passage to India is probably the most well-know English novel on India. The novel is about the trip of two English ladies to India. Written in colonial days, it helps to examine the establishment of cultural hierarchy in colonial India. In this thesis, I will analyze the establishment of cultural hierarchy and its impact especially on natives in colonial days, the lingering power of western cultural dominance in the post-colonial time, and the attempt to fight against it Keywords: cultural hierarchy identity crisis western cultural dominance Prologue “A magnificent novel of humane breadth and wisdom, comic tenderness and powerful political acuteness,” So said Hermione Lee, the chairwoman of the judges of the Men Booker Prize for 2006, when she announced that Kiran Desai, with her novel The Inheritance of Loss, won the prize. The novel may be a sweet and delightful saga of an Indian family, but its humor can hardly cover the bitterness which infuses the novel. Characters in this novel are trapped between two cultures—the dominating western culture and the ‘degenerated’ native counterpart—and find it difficult to solve the dilemma. Their struggles in the frame of stratified cultures remind me of the pessimistic ending of A Passage to India, another novel about India published more than 80 years ago. The novel ends in a riding that symbolizes the restoration of their relationship which was severed after the trial of a sexual assault, Fielding asks Aziz why they can’t remain friends, Aziz does not answer, but the landscape seems to say, “No, not yet… No, not there” (322). The ending expresses a strong uncertainty towards a solution to the tension between the East and the West. At a time when India was still the colony of Britain, there was no possibility to reduce the tension. Besides the political domination of the West, Forster, throughout his novel, indicates that cultural domination is probably the fundamental cause of the tension. It seems that the dominance of western does not end with colonialism; it survives history from colonial to post-colonial days.: Culture must be seen as essential to the creation, production, and maintenance of colonial relations. From this perspective, especially in the context of the spread of a global mass culture, globalization may be seen as the continuation and strengthening of Western imperialist relations in the period after decolonization and postcolonial nationalisms. (Hawley 214) That is to say, along with the continuous cultural domination of the West from colonial days to the current globalizing world, the tension which comes into existence with the colonialism has not been weakened in the postcolonial world. Thus, John Hawley emphasizes that all over the last century to the twenty-first century, “the structure of world power relations has remained largely the same” (214). By saying “largely the same”, it does not mean that there is no change. If in colonial days, the global power was centered in Western Europe, especially in Great Britain, now it has become to center in the United States (Hawley 214). This can be observed in The Inheritance of Loss that the cultural tension or conflict is not only between the British and the Indian as the previous colonizer and the colonized, but in a larger scale between the Indian and the western culture which is now anchored in the United States. Despite the power shift in the western world after the Second World War from Britain to the U.S., it is always the domination of the western culture that set India in a cultural predicament. Just as Kiran Desai writes in her novel The Inheritance of Loss, “Certain moves made long ago had produced all of them: Sai, judge, Mutt, cook, and even the mashed-potato car”. The Establishment of Cultural Hierarchy In Colonial Days In 1835, Macaulay wrote an educational Minute, which was to advise the British government of its policy on education in India. One of his statements, frequently quoted in later days, is that “we must at present do our best to form a class [in India] who may be interpreters between us and the millions whom we govern; a class of persons, Indian in blood and colour, but English in taste, in opinions, in morals, and in intellect.” His words are often regarded as the best footnote to the later cultural and educational policies adopted by the British administration in India. In the 1850s, English became the medium of instruction in some schools and universities in India. Through the language of English, the western culture was introduced to and accepted by a class of Indians. And the education of English language and culture re-stratified the Indian society. Those Indians who received western education were recruited into the British administration and thus won a respectful social status. In A Passage to India, Aziz, the doctor in the Civil Service is as respectful as Professor Godbole, a teacher at an English college. Though Professor Godbole is a Hindu of the Brahmin caste (the highest caste), Indians are no long classified by caste but by how well one receive English education. A similar situation can be found in The Inheritance of Loss, where the Judge, who is born in a farmer’s family, climbs up the social ladder and become a judge in the Civil Service through hardworking in a mission school and then in Cambridge University. It seems that in colonial days, the western language and culture were equated with power, and were therefore greatly admired among Indians. In this way, the re-stratification of Indian society by English education resulted in the establishment of cultural hierarchy—the western culture occupied a predominant position compared to the native culture. The fundamental reason for the British colonial culture to establish itself as superior to the native culture is to justify its dominance in India. On the one hand, the British colonists accepted this superiority so as to constitute its imperial power. On the other hand, the imperial center wanted to instill this kind of cultural hierarchy in its colonizers so that it would sustain the colonial power. Only when the British colonists accepted the cultural hierarchy could they feel righteous to govern India, whose culture was completely different from that of the West. Errington has analyzed how cultural hierarchy is instilled into colonists: [Colonial project attempted to] legitimize simple views of enormously complex situations and to license what were often fantasmatic representations of authoritative certainty in the face of spectacular ignorance. … [Sources of such certainty are] bound up with enabling ideologies about hierarchies of languages and peoples on colonial territory. (20) Indian culture might be very difficult for the colonists to understand and appreciate in a short time. Or probably they did not even intend to understand it at all. For British people, India was a colony, a territory not legally obtained. What they needed was a seemingly right reason to govern this land. Cultural superiority seemed to be the best excuse. Therefore, by setting up a “degenerated” image of native people partly through imagination or misunderstanding, they convinced themselves that native culture was far less sophisticated and refined than western one. When Ronny, in A Passage to India, claims that Aziz is not honest because “there’s always something behind every remark [a native] makes, always something”, he confesses that he does not judge the Indians in a way he judges the British and he picks up the image of Indian people from his older official Major Challendar. From this, the superiority and arrogance of British colonizers is clearly shown. What is more, they easily accept the “degenerated” stereotype of Indian people without any effort to understand native culture. The cultural hierarchy and racial stereotype of Indians is not only embraced by conservative authorities like Challendar and Ronny but also accepted consciously, and unconsciously by liberal humanists like Mrs. Moore, Fielding and Adela. Christensen argues that in A Passage to India the British characters—the conservatives such as Major Callendar and Ronny Heaslop, as well as the open-minded liberals such as Mrs. Moore, Cyril Fielding and Adela Quested—are all trapped by the racial stereotype on which the superiority of British culture develops. Thus all of them fail to cope with racism (173-174). In the article “The Prisonhouse of Orientalism”, Pathak express a similar view that Forster aims to critique liberal humanism and “chart the construction of the colonial subject in the […] individuals who consider themselves impervious to such construction” including Mrs. Moore, Fielding and Adela (383). Attracted by India, the liberal humanists come and desire to see a real one. But they seem unable to escape the trouble of discovering the true India. As Forster writes in his novel, “[India] calls ‘Come’ through her hundred mouths, through objects ridiculous and august. But come to what? She has never defined. She is not a promise, only an appeal” (136). The trouble is that British people in India, including those liberal humanists try to define the undefined invitation. They come to see what is “august” in their consideration, but not what is “ridiculous”. The Marabars cave is a representative scenery of India in Aziz’s eye, but Mrs. Moore and Adela do not think it is worth visiting and get disappointed. Mrs. Moore and Adela do not realize that to see the real India, they have to accept every part of it unconditionally. However, they are affected by the colonial images of India, and have their own imagination and expectation of what to see in India. Once what they see is not in accordance with their imagination or expectation, they feel disappointed and depressed in the caves. The acceptance of colonial images and the inability to accept the overall India show a sense of superiority of the liberal humanists. Therefore, cultural superiority is recognized among most of the British colonists and helps to constitute the colonial power. On the other hand, the imperial center attempted to inscribe the thought of cultural hierarchy in natives to sustain the colonial power. The most effective method may be English education. As Errington points out, the English language is a way for people from European centers to bond other tongues and cultures so as to rule. There is an interesting scene in The Inheritance of Loss which may reflect the power of English education on establishing cultural hierarchy among natives. A portrait of Queen Victoria is hung above the entrance to the mission school where the judge studies in. The portrait is a symbol of imperial power. Every day before the judge enters the school, he looks at her. Though the Queen seems to dress oddly, he finds that “her froggy expression compelling,” and feels “deeply impressed that a woman so plain could also have been so powerful. The more he pondered this oddity, the more his respect for her and the English grew” (58). There is nothing worth being awed at the fact that a plain looking woman can be so powerful as long as she was born in the royal family. It is simply his adoration towards British culture that makes him feel respectful to an unassuming Queen and her people. There is no direct evidence to show that the judge’s inclination towards Britain is a result of his English education, but the setting of the school may suggest so. For Indians, the acceptance of cultural hierarchy may be even more troublesome. It leads to some long-lasting personal dilemmas that hard to resolve. One of them is the identity crisis. The judge Jemubai in The Inheritance of Loss may be the best example. As a boy growing up under the colonial project, finishing secondary education in a mission school and college education in Cambridge, Jemubai becomes a faithful follower of Britain. Recruited as an ICS (Indian Civil Service) member, he makes great efforts to be an official “keeping up the British standards”. The pursuit of British standards shows his admiration toward Britain and his attempts to get into the imperial center. It also reflects his thinking that Britain represents a superior society to India. As Homi Bhabha points out that the powerful influence of a different culture will cause a tension between the desire of identity stasis and the demand for a change in identity; and mimicry represents as a compromise to this tension (86). When talking about mimicry of the center, Ashcroft claims that mimicry comes from a desire to be absorbed by the center, and it is this desire that causes “those from the periphery to immerse themselves in the imported culture, denying their origins in an attempt to become ‘more English than the English’” (4). It is true with the judge. He studies hard to obtain more knowledge about western culture. In addition, he also keeps up the British standards in his daily life: to have afternoon tea every day, to speak English with an English accent, and to cover his brown skin color with the powder puff. But all his efforts are futile; he cannot be accepted by the center. Even though he is in the ICS, a British-originated institution, he works only to reinforce the domination of Britain, and he is never regarded as equal by the British administrators. When returning to India, the judge is a ‘foreigner’ to his family, an awkward man with the habit of powder-puffing. The powder puff is the symbol of self-denegation. He uses the puff not for improving his looks or protecting his skin, but for covering his brown skin color—a cosmetic cover-up resulted from the racial discrimination he suffers during his study in Cambridge. At his arrival in England, the judge cannot find a house for several days, because the house owners do not welcome Indians. Attempting to get into the imperial center, the skin color becomes the eyesore and the biggest obstacle for the judge. He then figures out to disguise, by the use of the powder puff. But back in India, powder is rarely used and if being used, it is only for the women. The family members cannot understand the judge’s behavior and some even mock him. A big fight bursts out between the judge and his family, especially between the judge and his wife; a sense of estrangement is set up between the judge and others. Therefore, the judge suffers a kind of double isolation. On the one hand, he is cut off from the colonial center. On the other hand, he is cut off from his culture and his family. And the double isolation traps him in the “identity crisis”. Regarding different connotations of the search for identity, Sudhis Kakar says “at some places identity is referred to as a conscious sense of individual uniqueness, […] and at yet other places as a sense of solidarity with a group’s ideal” (R. S. Pathak 52). There are two aspects of “identity” in the process of cultural exchange. First, the “uniqueness” in fact emphasizes the difference. The necessity to form an identity comes from the representation of difference. Second, the “group’s ideal” may refer to the culture which is the expression of particular community. And the solidarity with the group’s ideal implies the identification with certain culture and its people. It is both the cultural difference and identification with the cultural tradition that defines one’s identity; and the denegation of either may result in a state of loss. Yet the “difference” here implies no cultural hierarchy. If the difference indicates a kind of superiority or inferiority, just as what the Judge considers, then it falls into the colonial mentality that all the reality and truth is established by the dominant. Thus the identity is unreal and the real identity is lost. That is why it is from the denial of the cultures as incommensurable and acceptance of the cultural hierarchy that all cultural conflict occurs. The judge’s pursuit of British standards and attempts of disguising his skin color implicates his complicity to the cultural hierarchy which denies the “difference” as incommensurable. On the other hand, his failure to get into the center and his isolation from the Indian culture and his family corners him that it is impossible for him to form any meaningful cultural identification. He is stuck in an “identity crisis”. In The Inheritance of Loss, the judge is later aware of the impossibility of getting into the ‘centre’ despite his mimicry of it. When eating the chicken proclaimed by the cook as roast bastard instead of roast bustard, which reminded him of the Englishman’s jokes on natives using incorrect English, he realized people like himself—the Anglicized Indians—are also the subjects of these jokes. No matter how hard he tries to cover his skin color and to follow an English lifestyle, he remains as an Other, as inauthentic to the British. Even if he gives up the attempt to get into the “center”, his belief in cultural hierarchy will never be eliminated. “Mimicry” and “ambivalence” are important concepts in the theory of Homi Bhabha. He explains the ambivalence of mimicry as both a resemblance and a menace. Yet regarding the judge, whether mimicry will function as to disrupt colonial authority is doubtful. If the resemblance may be achieved passively or unconsciously by the indoctrination of colonial discourse, the actual resistance is autonomous. It is the acceptance of cultures as incommensurable that creates the site of resistance. For the judge, the site is inaccessible due to his colonial mentality. Those agreeing with the incommensurability of culture will have the autonomy of resistance since the cultural hierarchy established by the colonial power is not right. But the judge believes “the truth” told by colonizers that cultural hierarchy exists, and that the West is superior to the East. His belief prevents him from viewing cultures as incommensurable. The judge cannot understand that the denial of cultural hierarchy is the power to challenge the dominant, to unsettle the authentic and to disturb the centre. As we observe in The Inheritance of Loss, even though the judge experiences racial discrimination in Britain, he is still looking forward to an India dominated by Britain and the British lifestyle. He blames the disorder of India on the Indians and the Indian culture rather than the colonizers. The Lingering of Colonial Thought E. M. Forster suggested in A Passage to India that the independence of India would possibly relieve its tension with the British imperial power. Yet the elimination of colonization might effect alleviation but was hardly a termination to the tension. In the end of his novel, Forster expresses a sense of uncertainty towards a “visionary resolution”, which in Malcolm Bradbury’s view the novel was close to offering. Since he did not witness the end of colonization, Forster is pessimistic about the friendship between the two nations in a period when colonization still existed. Edward Said has commented, on this pessimistic ending, that it leaves “a sense of the pathetic distance still separating ‘us’ from an Orient destined to bear its foreignness as a mark of its permanent estrangement from the West” (244). Though uncertain and pessimistic about the future, Forster might not expect the tension and estrangement to be “permanent” as Said concludes. Said has his righteousness from the perspective of a contemporary, whereas the awareness of the continuity of western domination after colonization produces a sense of “permanence” as it lasts such a long time. Forster probably would not have imagined that six decades after India’s political independence, his conclusion is still valid. No resolution is found and the tension, though more cultural than political, is still there. Kiran Desai in her novel The Inheritance of Loss expresses her idea that the fate of the Indians who were trapped in the East and West in the current age of multiculturalism and globalization seems to be doomed since the age of colonialization. This continuous cultural domination of the West nowadays results in the lingering of cultural hierarchy. The idea that western culture is more advanced and refined lingers in India. In colonial days, when the cultural hierarchy was accepted by Indians, they appeared as great admirers of western culture. The opening conversation in A Passage to India clearly shows the natives’ preference of the West. A young Indian man loudly declares that, “I admire them [the British].” The idea that the West stands for the civilized while the native does not still widely exist among many Indians. When Biju, the son of the judge’s cook, applies for his visa in the U.S. embassy, he is with a group of Indians struggling to reach the counter window. The biggest pusher among them tries hard to impress the U.S. officials that he is civilized: He dusted himself off, presenting himself with the exquisite manners of a cat. I’m civilized, sir ready for the U.S., I’m civilized, mam. Biju noticed that his eyes, so alive to the foreigners, looked back at his own countrymen and women, immediately glazed over, and went dead. (183) It is probably one of the most agonizing scenes in the novel. Their eagerness for a U.S. visa results from a fancy image of the West as orderly and civilized. By accepting that the West represents the civil, the Indians actually deny themselves the possibility of being civilized. Since the stereotype of India as uncivilized has been established long ago by the imperial center, it is only by challenging the center so as to unsettle its establishment. There is no chance for people from the periphery to get into the center, for the acceptance undermines the antithesis which grants the center the privilege of the dominating power. The older generations of Indians who are inscribed with colonial mentality unconsciously become the helpers to spread the western culture and reinforce the western hegemony. Lola and Noni who live in the same village with the judge in Kalimpong are typical Anglophiles. They grow broccoli with seeds procured in England, wear Marks and Spencer panties, listen to BBC, read nineteenth century British novels, keep an empty jam jar with “By appointment to Her Majesty the queen jam and marmalade manufacturers” written on its coat. Lola is so proud of her daughter being an anchor at BBC and she asks her to seek residency and not to come back ever after. The cook always tells his son Biju his American dream of obtaining sudden wealth and living a modern life and makes every possible attempt to send Biju to the U.S. The judge asks Noni to teach Sai instead of sending her to a public school in Kalimpong because he believes that Sai will learn the Indian-accented English in public school. The older generation passes down their colonial mentality to the young. Though it does not mean that the young will think as exactly as the older, the colonial thought is to some extent passed down. On the other hand, till now the cultural hierarchy has not been rooted out in the West. In colonial days, Indians were recruited into the British administration, but they were never really respected by the British people. When Aziz encounters two British ladies, he lifts his hat to show his courtesy, but the two ladies just turn instinctively away. And then they take Aziz’s tonga without a sign of gratitude. While in the welcome party of Mrs. Moore and Adela, they are informed by their compatriots to keep distance with natives because most Indians are “seditious at heart”. In postcolonial world, in the eye of the West, the Indians, the people from the Third World remain at the bottom of society; their rights have not been guaranteed. In the basements of New York restaurants, as depicted in The Inheritance of Loss, are full of illegal immigrants form the Third World. The wage is little and the dream of wealth remains far away. They are being exploited, but they are unable to change their status. The boss cut down their wages and living expenses, so that there will be more money put in his own pocket, but he or she will not spend a penny to sponsor them for green cards. Lingering of cultural hierarchy ensures the West to remain in the position of “center”, as its cultural influence is still dominant over the world. Through those who have accepted this colonial thought and through those TV programs and movies sold to other countries, the “reality” of center is told and the image of orderly, civilized “center” is continuously set up. What may be different in the post-colonial time is that some have realized the forceful yet destructive power of cultural hierarchy and attempt the fight back. In The Inheritance of Loss, We can perceive the attempt to resist western domination from the young people such as Biju, Gyan, and Sai, though the resistance is hardly effective. They are a little different from the judge and the cook who accept the existing cultural hierarchy whole-heartedly and make no effort to resist. They try to resist but they are still trapped by the influence of the West. Biju is sent to the U.S. by his father with a traveling visa. After his visa is expired, Biju works illegally in the basements of New York restaurants with many other illegal immigrants form the Third World. Biju comes to the U.S. with his, or rather his father’s “American dream”, since it is always his father who tells Biju how modern the U.S. is and how easy to get rich there. Throughout the novel, Biju is fond of the modernity of the U.S. which he does not have the chance to experience though he is in the States. However, being in the west reveals to him another side of it, that is, the disorderly and the uncivilized side. The presupposed cultural reality of the west begins to collapse. One day, Biju amazingly discovers that Indian men in New York restaurants orders beef without hesitation. The behavior is certainly against Hindu observance, but it seems that they do not care at all. He at once feels repulsive towards this disorderly situation: “One should not give up one’s religion, the principles of one’s parents and their parents before them. No, no matter what. You had to live according to something.”(136) Biju’s reaction or resistance toward the uncivilized of the West is a little more forceful when later Biju understands that he, with many other illegal immigrants in the restaurant, is actually being exploited. He has a fight with his boss, but what seems pathetic is that his fury about the imperial exploitation does not reduce his fondness of the modernity in the western society. Before Sai comes to live with her grandfather, she studies in a convent school where English is the teaching language and the English culture is what she learns. She leads a relatively lonely life in her grandfather’s mansion in Cho Oyu until she meets Gyan, the Nepali tutor. The different backgrounds in which they grew up lead to diverse attitude towards the western culture and finally threaten their relationship. Gyan is aware of their different backgrounds when first dining with Sai, because Gyan uses his hands without a thought and Sai eats with a fork. Gyan is not familiar with the western way of eating. Later when he dines at the judge’s house, his awkwardness with the fork and knife is shown again. Interestingly, he feels ashamed about it. The sense of inferiority surging in Gyan is a result of his fondness of the western style yet his unfamiliarity with it. Annoyed about feeling inauthentic in the western culture which Sai and her grandfather are immersed in, Gyan retreats to his own culture so as to refuse the approaching any other culture. Joining GNLF (Gorkha National Liberation Front), he submits to “the compelling pull of history and found his pulse leaping to something that felt entirely authentic” (160). Among Nepalese, he recovers a feeling of identification by mocking on the judge’s mimicry of the western lifestyle. Yet the attempt to be isolated from other cultures is only a temporary illusion, since “within the syncretic reality of a post-colonial society it is impossible to return to an idealized pure pre-colonial cultural condition” (Ashcroft 108). In fact, even those participants in insurgency are not un-influenced by the western culture. They wear T-shirts of American brand and admire Bruce Lee, an icon of martial arts in Hollywood. As nowadays, more and more parts of the world are cross-related, rendering cross-cultural exchanges and influences inevitable. Gyan’s relationship with Sai breaks up in a series of quarrel beginning from Christmas, which indicates his own dilemma in the encounter of two cultures. Sai sharply points out Gyan’s fondness of the West and it is hypocritical and stupid for him to take refuge in the Nepali culture for a sense of authenticity. When fighting on Christmas day, Gyan argues that it is completely nonsense for a non-westerner to enjoy such a holiday, while Sai insists that it is only an excuse for a party, which shows her broad-mindedness toward a different culture. Grown up in the convent school, Sai, like her grandfather, speaks English better than Hindu and has a lifestyle more English than Indian. But that does not mean she is an Anglophile like her grandfather. She refuses to accept the idea that the Indian culture is inferior. She feels humiliated and angry after she reads a paragraph written by an English writer, which advises all the Indian gentlemen, whether or not they have required the habits and manners of the European, not to enter into the compartment reserved for Europeans. The writer suggests that Indians should enter the one set apart for them because of their race. This is a piece of writing full of the sense of superiority as the colonizer intending to inoculate Indians with the colonial mentality, Sai feels angry about it and at the same time realizes the lasting domination of the western culture after the independence. She is grown up in the hybridity of two cultures and she can accept the difference of them peacefully. But her own journey has not started yet. She receives complete English education and has limited experience or knowledge about the cultural tradition in India. Cultural dilemmas such as issue of identity will probably trouble her. Conclusion Paul Armstrong suggests that A Passage to India reflects Forster’s “recognition of the impossibility of reconciling different ways of seeing”(365). His argument is fairly accurate, for Forster leaves us a very uncertain ending. Forster has realized that what underlies the prominent political conflict between India and the West is the cultural difference. Though Forster may be pessimistic about reconciliation of different cultures, he clearly indicates in his novel that westerners’ attitude towards another culture is improper. Their sense of superiority, their arrogance as the conqueror of the mystic East and their ungrounded prejudice towards Indians are all improper. Cultures are incommensurable. The difference of culture is supposed to be regarded as a mere existence and suggests no cultural hierarchy. In colonial India, culture difference indicates a kind of superiority or inferiority. From the denial of the incommensurability of cultures and the acceptance of cultural hierarchy, cultural dilemma like identity crisis occurs. The denial creates the superior and the inferior, the centre and the periphery, the dominating and the dominated, order and disorder, the authentic and the inauthentic, the powerful and the powerless. In the post-colonial world, this colonial mentality has to be rooted out, and the central position of the West destructed. Otherwise all the reality and truth will be established by the dominant center just as in colonial days. Kiran Desai, with her novel The Inheritance of Loss, challenges the dominance of the West and the “reality” of an orderly, civilized “center” told by the West. In her novel, the depiction of New York City, the center of the center, reveals its disorder—the basements filled with illegal workers, and its uncivilness—religious people taking no notice of the religious disciplines. By showing the same “disorderly” and “uncivilized” state both in the center and the periphery, Desai unsettles the western hegemony and destructs the reality of center. The West no longer has the privilege to tell reality. The East has its chance to tell its version of reality and truth. The Inheritance of Loss ends with the depiction of nature: “The five peaks of Kanchenjunga turned golden with the kind of luminous light that made you feel, if briefly, that truth was apparent.” For those Indians who have been silenced since the dominance of the West, they seem to get the chance to tell their version of reality. Though their voice may be brief, it is a meaningful attempt. Works Cited Armstrong, Paul B. “Reading India: E. M. Forster and the Politics of Interpretation”. Twentieth Century Literature, Vol. 38, No. 4, Winter, 1992, pp. 365-385 Ashcroft, Bill, Gareth Griffiths and Helen Tiffin, eds. The Empire Writes Back. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge, 2002. Bhabha, Homi K. The Location of Culture. London: Routledge, 1994. Bradbury, Malcolm, ed. Forster: A Collection of Critical Essays. New Jersey: Prentice Hall Press, 1966. Childs, Peter, ed. Post-Colonial Theory and English Literature: A Reader. Edingurgh: Edinburg University Press, 1999. Christensen, Timothy. “Bearing the White Man’s Burden: Misrecognition and Cultural Difference in E. M. Forster’s A Passage to India.” Novel: A Forum on Fiction Spring 2006, Vol. 39 Issue 2: 155-178. Desai, Kiran. The Inheritance of Loss. New York: Grove Press, 2006. Errington, Joseph. “Colonial Linguistics”. Annual Review of Anthropology, Vol. 30, 2001, pp. 19-39. Hawley, John C., ed. Encyclopedia of Postcolonial Studies. Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 2001. Hubel, Teresa. “Liberal Imperialism as A Passage to India.” Post-Colonial Theory and English Literature: A Reader. Ed. Peter Childs. Edingurgh: Edinburg University Press, 1999: 352-362. Pathak, R. S. Modern Indian Novel in English. New Delhi: Creative Books, 1999. Pathak, Zakia, Saswati Sengupta and Sharmila Purkayastha. “The Prisonhouse of Orientalism.” Post-Colonial Theory and English Literature: A Reader. Ed. Peter Childs. Edingurgh: Edinburg University Press, 1999: 377-386. Said, Edward. Orientalism. New York: Penguin, 2003. 后记(致谢): 首先,我想感谢莙政学者项目给与我这次机会参与本科生的学术研究项目。通过莙 政项目,我得到了学术研究的初步训练,懂得如何确定、研究和完成一个课题的必要流 程,并为我今后继续接受学术研究的训练打下了一定的基础。也感谢莙政学者项目提供 资金支持我的研究项目,使我能够购买到一部分国外的出版的书籍,开拓资料收集的范 围,了解了一些国外的研究理论以及视角。 另外,我非常感谢卢丽安老师对于我的项目的指导与支持。卢老师认真负责的指导 使得我在项目中受益匪浅。她对于研究方式、视角,研究规范方面的指导帮助我最终完 成了这一课题,也让我对学术研究有了基本的概念。 最后,我想说,我在这次项目中感受到了学术研究的乐趣,并有志于继续这方面的 研究。