Assessment Design Briefing Paper

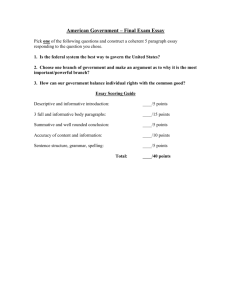

advertisement

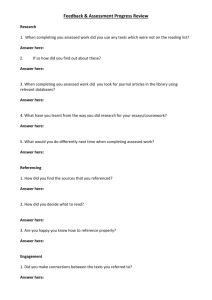

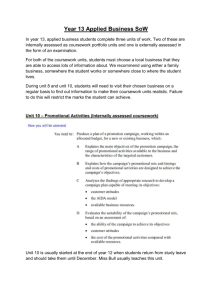

Assessment Design - Briefing Paper Introduction Assessment of student learning is probably the most important thing we do as academics: ‘Get assessment wrong and you get everything wrong… Assessment is the most important single component in student learning’ (Biggs, 1999). Students need assessment to support them and focus their learning (assessment for learning), whilst a range of other stakeholders require the outcomes of the assessment process to make judgements and decisions about students, the course, the department and the institution (assessment of learning). These guidelines will deal with both these aspects of assessment, looking at how current practice might be evaluated and improved – at the same time as keeping the burden of assessment within manageable bounds. Feedback to students is dealt with in a separate guideline. Why do we assess? For the students: To provide feedback on learning To indicate required standards of work and set expectations To motivate and encourage To engage in dialogue with students about the discipline assessed coursework are all examples of formative assessment. Summative assessment provides a formal judgement, invariably with a mark attached. Exams and coursework which contribute to a final degree classification are both examples of summative assessments. Of course, some assessment may be both formative and summative: assessed coursework can provide feedback and inform future learning for students but at the same time result in a recorded mark that will count towards a final grade. Some potential problems with assessment The way in which courses and modules come into being can lead to a number of dangers. Frequently people may think about their own module but do not necessarily look at the bigger picture and how the way they assess articulates with other assessment experiences students are having. Typical problems in assessment design are: For ourselves, the institution, employers and others: To check students are benefiting from our teaching Measure progress of students against expectations Part of the process of gate-keeping to the next stage of study As a quality assurance indicator Setting and maintenance of national standards Provide evidence for award of a degree or diploma Formative assessment is a vital part of the learning process whereby students can have feedback and dialogue about their learning which will feed into later work. Self-assessment (formal and informal), non-assessed tasks, Over-assessment leading to an excessive burden for students and staff Using a limited range of assessment so that some skills are repeatedly assessed (e.g. essay-writing) whereas others (working in groups, problem-solving) are assessed only rarely. Not matching assessment tasks to the desired learning (e.g. assessing groupwork skills by essay) Assessment which favours particular characteristics or approaches to learning (e.g. assessment only by timed, end-ofmodule tests may put non-native English speakers at a disadvantage) Evaluating your current approaches A well-designed assessment strategy will have the following characteristics: Be designed in such a way that the total assessment experience of students is coherent, timely, meaningful, realistic, and stimulates, motivates and contributes to learning Provide meaningful feedback to staff on students’ achievements and development 1 Match assessment tasks to desired learning outcomes Be balanced between the need for assessment of and for learning Demonstrate progression so that students are challenged at increasingly sophisticated levels as they progress through their studies Recognise the range of student abilities and preferences by providing a rich mixture of assessment experiences and choices of method where appropriate From the staff perspective, recognise constraints of time, issues of plagiarism, and accountability within and outwith the institution (eg to employers, professional bodies etc) Although we regularly formally evaluate our teaching, we rarely do the same with our assessment approaches. Indeed, course evaluation is often undertaken before students can comment on the full range of the assessment they are required to do: how often do we ask about experience of exams, for example? So how can you evaluate how assessment strategies are impacting on students? Here are some suggestions taken from the Integrative Assessment project (QAA 2007): 1. Plug gaps in monitoring students' experiences eg ask students about their experiences of exams and tests, the consistency of feedback and marking, the weighting of different kinds of assessment, how different types of assessment compare with one another. 2. Tap into their wider assessment experiences eg ask questions about their experiences across modules/course units, across different years/levels of study, or different subject areas. 3. Combine questionnaires with other methods like focus groups or Blackboard discussion sites. 4. Focus in on changes in assessment practices or procedures eg ask students to comment on how they are affected by changes in procedures or methods. 5. Ask different kinds of questions eg what one thing would really improve how your work as a student is assessed? 6. Rethink when to ask students for their views eg carry out a brief survey mid-term or midsemester, while there is still time to address major concerns. 7 Review what background information you ask of students eg have they studied the subject before, and how well they did; are they likely to take further courses in the future; do they live on/off campus; do they have a job in termtime; do they come from an Englishspeaking background? 8. Focus in on areas of known student concern eg where past evaluations have indicated student discontent with the provision of guidance and feedback. 9. Survey staff as well as student experiences and perceptions of assessment particularly where teaching and assessment responsibilities are spread across a large and diverse course team. You might also use existing data to draw conclusions about the effects of assessment approaches or what the results of summative assessment can tell you about your teaching. Using a range of valid, reliable stimulating assessment: Examples and Assessment methods need to align with intended learning outcomes and fit well with teaching approaches – what Biggs refers to as ‘constructive alignment’ (Biggs, 1999). Methods must also be fair and make sense to students – e.g. it is not helpful if the first time a student has to be assessed on a particular topic is in the exam. Although most people have clear assessment criteria for pieces of work, it is important to remember that students need help in interpreting what these mean. Essays: try a three-stage process where students submit a draft, a bibliography and then a full essay. (McCreery, 2005). Portfolio: students following a course in Translation and Interpretation at the University of Hong Kong submit a portfolio, consisting of seven types of documents which touch on the 2 main issues covered in the module, as evidence of their learning on the course. (Mak, 2006) Independent research: Final year undergraduates in science and technology at University College London carry out an independent research project, then submit an essay and their research methods and materials before sitting an exam which tests their understanding of one another’s work. (Chang, 2005) Web pages: At the University of Strathclyde postgraduate students on the Energy Systems and Environment programme present a group project as a web page in the form of a logbook. (Stefani, 2002) At Lancaster University undergraduate history students produce web pages as part of the assessment for their degree. The section about the history of Lancaster University on its home page is an example of this: http://www.lancs.ac.uk/unihistory/ (Winstanley, last accessed Feb 2007) Peer assessment: sports studies students at St Martin’s College were involved in an exercise where they used tutor-generated assessment criteria to evaluate their peers’ work, but were also assessed by their tutors on the marking and feedback comments they proposed for their fellow students. (Bloxham & West, 2004) Blending a range of assessments to promote deep learning: on the MSc in Interprofessional Studies at the University of Wales Institute Cardiff assessment is via a group task comprising a group portfolio, a joint presentation, an individual essay and peer review. (Connor, 2005) Links Most of the above examples are taken from the four guides produced by the Integrative Assessment enhancement theme project: www.enhancementthemes.ac.uk Other sources Knight, P. (2001) Skills plus: employability and assessment http://www.heacademy.ac.uk/documents/paper4 .rtf Higher Education Academy case resources database: http://www.heacademy.ac.uk/4908.htm study What to do now? 1. Using the Planning Tool, work out what currently goes on in your assessment on your course. 2. Decide which other approaches and methods would work in your subject area. 3. Plan how they will map across the course, developing graduate attributes at each level. 4. Make sure that the approach is explicit and understood by students and colleagues: they are more likely to engage with tasks if they can see the point of them. Computer-aided assessment: students on the Labour Economics and Education Economics course at Lancaster University can monitor their own progress by using interactive quizzes: http://www.lancs.ac.uk/people/ecagj/quizzes1.ht ml (Johnes, last accessed Feb. 2007) E-feedback: A book publisher’s system, Mastering Physics (MP) was implemented in the School of Physics at the University of Sydney to deliver assignment/tutorial questions to students. The MP offers immediate feedback ad marking to students, and reduces copying of assignment since all students must complete the assignment under their own login. (O’Byrne, 2006) 3