Working Mothers` Contribution to Family Income

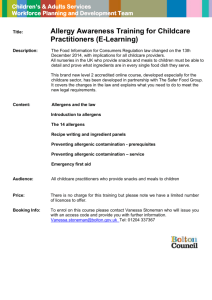

advertisement