The Relationship between Housing and Education

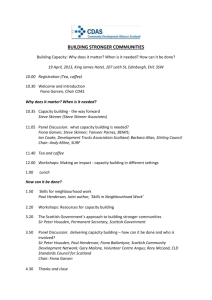

advertisement