Maternity Services Literature Review DPHQA Final 06.07

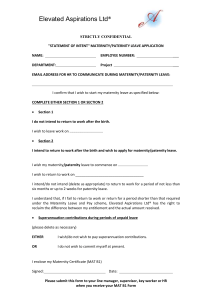

advertisement