family, economics, and the information society

advertisement

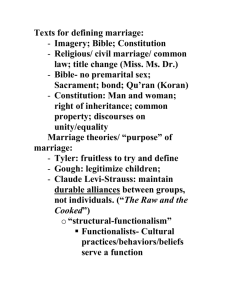

FAMILY, ECONOMICS, AND THE INFORMATION SOCIETY HOW ARE THEY AFFECTING EACH OTHER? Maria Sophia Aguirre Associate Professor Department of Economics The Catholic University of America Washington, DC 20064 Paper Presented at the World Conference of Families II Geneva, November 14-17, 1999 I. Introduction In this century the United States, as well as many other developed countries have gradually moved from being mainly an "agricultural-based industrial society" to an "information society", or "post-industrial era society." The second part of this century has also been marked by a serious deterioration of social conditions in a majority of the industrialized countries. The combination of these two factors has posed to countries both serious challenges and economic burdens. To these challenges countries have responded in different ways. Some have focused on welfare issues, some on financial issues, and still others have chosen the route of ignoring this matter altogether. More recently however some of the developed countries have chosen to address what is at the heart of both the social deterioration and the economic problems it brings; that is, they have begun to reevaluate and promote policies that strengthen and support the family. Fukuyama (1999) proposes three economic structural characteristics of the post-industrial era. First, services increasingly displace manufacturing as a source of wealth. As a consequence, instead of working in a factory the typical worker in the post-industrial society is employed in a bank, software firm, hospitality carrier, university, or social service companies. Second, the role of information and intelligence embodied in both people and computerized machinery has replaced to some extent physical labor with mental labor. Third, the production is globalized as inexpensive information technology makes it increasingly easier to move information across international borders. Rapid communication by television, radio, fax, and e-mail erodes the boundaries of cultures and countries. People tend to associate the information age, as Fukuyama 1 (1999) remarks, with the introduction of the Internet in the 1990s, but the shift away from an industrial era started more than a generation earlier. This shift started with the deindustrialization of the Great Lakes in the United States and with comparable moves away from manufacturing in other industrialized countries. During the period from 1960 to the early 1990s, crime and social disorder began to rise, making inner-city areas a dangerous place to live. Fertility in most developed countries fell below replacement levels, causing a reversal of the age pyramid; marriage and childbirth were less frequent while divorce rates soared; and out-of wedlock childbearing affected many. For instance, one out of every three children born in the United States and over half of all children in Scandinavia are born out of wedlock1. significantly declined. Finally, trust and confidence in institutions have All of these factors are very relevant for economic growth and development in any economy since they hinder the most important resource: the economic agent and with it human capital. Furthermore, trust is a basic condition for any economic activity for without it, any economic transaction becomes very expensive or is avoided. One can think as an example of the importance of trust for economic activity, on the capital flight that less developed countries experienced during the 1980s. Trust on these countries’ capacity to perform was lacking and the capital flight that followed as a consequence was very harmful for these economies. Another example would be the problems caused for public health plans by distrust, on the part of Indian women due to some abuses in the area of reproductive health. This has often caused mothers to not vaccinate their children and to avoid prenatal care needed for healthy pregnancies. Fukuyama (1999) claims that the accumulation of these negative social trends is closely related to the transition from the industrial to the information era. The relationship is established by the link that exists between technology, economics, and culture. The changing nature of work, which substituted mental for physical labor, propelled millions of women into the work place and undermined the traditional understanding of family roles upon which the family had been based for centuries. Innovations in medical technology, like contraceptives distorted the role of reproduction and the family in peoples lives. The culture of individualism, which in the market place encourages innovation and growth, spilled over into the realm of social life, 2 corroding virtually all forms of authority and weakening the bonds that hold families, neighborhoods, and nations together. There is a bright side however: social order, once disrupted, tends to get remade once again, and there are many indications that this is happening today. Families and governments are reevaluating the role that family plays in the economy and in society. Working women and men are searching for alternative working arrangements to make family and work obligations compatible. There is an overall search for moral principles that could establish some common denominator in an ever-diverse multicultural society. One may ask why one could have expected this to happen. The answer can be found in human nature. Men by nature are social creatures and the family is its basic unit and most important manifestation. In this paper, I will try to address two questions. First, how can we view the family within the economic activity?; and second, why are the breakdown of the family and policies that encourage this breakdown incompatible with sustainable real economic development? In the second part of the paper I address the first question and the analysis of the second question follows in the third section. In the fourth part I refer to some of the positive initiatives being proposed in developed countries to solve some of the present social conditions and costs. The paper ends with few conclusions. II. A View of Family and Economic Activity When addressing the relationship between family and economics, it is important to consider the characteristics of the family and how the economy relates to these characteristics. The first characteristic of the family is that it is the first form of society. A person normally comes into the world within a family, and it is within a family where the child first develops and matures as a human person. If life develops within the family, then we can say that a second characteristic of the family is that it is a "living being", as expressed by the Spanish philosopher Rafael Alvira (1987). If it lives, then it has a principal of action and a material substance. The principal of action of the family is love, and the material substance is the economy. Two important expressions of this love are intimacy (the key to a home atmosphere of respect, trust, and joy) and education. Nature has given the parents not only the capacity to bring life, but to 3 help each child develop (that is, to help their children with what is in them at first 'capacity' to becomes 'actuality', i.e. habits and therefore education). In doing so and in providing for the right atmosphere, they are expressing their love for their children. The members of the family are human beings and, therefore, they are in need of material things to develop. It is the need to obtain and to consume these material things that explains the reason for economics and the role that the family plays in it. In this sense then, we can say that the family is the first and most fundamental place where production and spending acquire their meaning. It is precisely in the ability to foresee both the needs of families and the optimal allocation of productive factors to satisfy those needs, which constitute an important characteristic of a well functioning economy. Many goods cannot be adequately produced through the work of an isolated individual but they require the cooperation of many people working towards a common goal. Furthermore, production and spending are neither mere 'individual' things to do nor mere 'social' things, but they are human activity and therefore must be directed towards meeting family needs. If they do not, spending leads either to consumerism or to controlled and planned economies. In summary, consumption and the means necessary for production (such as private property) are not an end in themselves, but an instrument to provide the family with the means of subsistence and development. It is within the family domain that private property encounters its meaning because it is in the family that the economic agent finds motivation to work. At the same time, it is in the family that pure selfish motives for economic activity are overcome because the person's work is directed to meet the needs of the other members of that family. The ground on which capitalist theories have defended private property has been the economic agent's work. These theorists maintain that a given economic agent carries out work and therefore he is the owner of it. Thus, he has the right to keep and enjoy it. This justification however, is incomplete since no one could have worked having not first received an education. Furthermore, no one can work without the help of others. Thus any product or source of production to some extent, is not the economic agent's alone, but some other members of that society have rights upon the same product. This implies that it is possible to find support for the right to private property in an economic agent's work, but not absolute private property. 4 Private property encourages production and belongs to someone, but the product of this property transcends the owner since he does not work in isolation or for himself alone. Another sign that confirms that the economy goes beyond the needs of a sole individual is the need to distribute the goods produced in the economy. This need is mainly felt in the family and it is for this reason that it is through the family that the economy transcends the mere individual level. This is an important idea when thinking on income distribution theory and policy as well as on sustainable real economic development. Distribution within the family is carried out usually through women. It is here that the most important role of women in the economy is found: woman, because of her characteristics, has the capacity to distribute goods in a just manner, according to the specific needs of each member of the family. Using the previous analysis, we can understand why several elements of the economy degenerate if they are not ordered towards the family: how is a good distribution possible without reference to the family? What is the point of an economic agent saving or investing beyond retirement (i.e. future consumption) without the family? What moderation would there be in consumption and spending if there were no family? What is the motivation to work without a family? What is the role of government if not to meet, at least in a subsidiary manner, the needs of the family? An economy that is based on profit and selfish individualism could be successful for a period of time, but it will not last (among other things because it will not produce enough population without which no economy is possible). It is the economic agent – man – that works, and man naturally belongs to a family. Since it is also the case that man develops within the family, then it follows that the economic agent will contribute the most to society, and vice versa when the family is being promoted by the economy in which he works. Gary Becker, in his theory of human capital, when considering investment in human beings (education) and its effect on real economic growth, points out that "no discussion of human capital can omit the influence of families on the knowledge, skills, values, and habits of their children.2" He goes on to say "parents have a large influence on the education, marital stability, and many other dimensions of their children's lives," and -one can add- therefore on their present and future productivity. So far we have seen that family consumption needs give rise to economic activity, and that 5 the families affect the productivity and consumption of the economy by the influence that it exercises on each of its members. At the same time, as the members of these families contribute to the economy, private property and other institutions and services such as health services, housing, education, social securities, national security, etc., develop so as to complement and meet the needs of these families. Therefore, if we are to understand any economic issue, the way in which that given issue affects the family as a whole or a given member of it, must be evaluated carefully. This is directly and indirectly the most important reason for economic activity. III. The Breakdown of the Family Institution and Sustainable Real Economic Development From an economic point of view, family is very relevant for several reasons. First, the breaking down of the family is a symptom of social weakening, which is detrimental to the economy because of the social cost entailed, especially for government finances. Second, children develop better within a well functioning family, that is, with their biological parents in a stable marriage. Thirdly, a child's academic performance is directly related to family structures, which is an important aspect of human capital. This section of the paper will address these points from the dimension of the cost that developed economies have incurred as the breakdown of the family spread during the second part of this century. 1. The Break Down of the Family: Divorce and Illegitimacy The changes that have taken place in Western families are familiar to most people and are captured in statistics on fertility, marriage, divorce, and out-of-wedlock childbearing. This is also reflected in the rise of welfare cost to support broken families as well as its side effects: child re-habilitation, programs to deal with crime, drug abuse, teenage pregnancy, special education, and aging populations. For example, in the United States, 1998 family assistance expenditures were 5 times higher than in 1970 in real terms, and health expenditures increased 15 times during the same period. Also in real terms, health expenditures increased by $225 billion between 1991 and 19963. In addition to the welfare cost incurred, there is also an immense legal cost involved. Billions of dollars are being wasted at the courts while these funds could be used in more positive constructive ways. These factors affect social stability and therefore affect the 6 economic development of a country. Like fertility rates, marriage rates experienced a rise in the 1960s in the US, Netherlands, Canada and other developed countries. Since the 1970s however, marriage rates have been falling rapidly while divorce rates have soared. Approximately 50% of the marriages contracted in 1980s in the U.S. can be expected to end in divorce. The ratio of divorced to married persons has increased even faster due to the decline in marriage rates. In the case of the US, this increase has been fourfold in the space of thirty years, and it is the same for Europe4. Figure 1 shows the rate of birth to single mothers between 1950-1998. Children born to unmarried women as a proportion of live births for the US climbed from 5% to 35% from 1940 to 19985. However, illegitimacy ratios vary significantly by race and ethnicity. In 1998, the ratio for whites was 23.6%, and for African Americans 68.7%6. Between 1994 and 1997 the proportion of births to single mothers in the US leveled out. Part of the explanation for this phenomenon has been the decrease in teenagers’ birth rates. The number of teenagers giving birth fell from 61.2 per 1000 women to 54.7 in 1991, but significantly increased thereafter. It is important to notice that the significance of illegitimacy is different in Europe than it is in the United States, due to the high rate of cohabitation in Europe. For example, between 45% and 90% of people between twenty and twenty five years are cohabiting in Northern European countries, while at the same time the marriage rate it is very low (about 3.6 per 1000 inhabitants7.) Comparably, in the U.S. 14% of the people between twenty and twenty-five are cohabiting8. The U.S. still stands out however, for the number of children born to mothers living alone, or to teenagers9. The number of children living in single-parent families in any given year is the product of several factors: the rates of out-of wedlock births, cohabitation, divorce, dissolution of cohabitation arrangements, and the re-marriage and re-cohabitation rates. The United States has the highest rate of single-parent families because it has a high illegitimacy rate, a high divorce rate, and a low cohabitation rate relatively speaking. Co-habitation is more unstable than marriage. Bumpass and Sweet (1986) find that unions that began by cohabitation are twice as likely to dissolve after ten years than unions that do not. Also, they report that marriages entered Figure 1 7 Out of Wedlock as Percentage of All Births Births to Single Mothers, 1950-1998 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 United States United Kingdom Japan Sweden 1 95 0 1 95 6 1 96 2 1 96 8 1 97 4 1 98 0 1 98 6 1 99 2 1 99 8 Year Sources: National Center for Health Statistics of the Countries Used. into after a period of cohabitation are less stable than marriages without prior cohabitation. More recently, Popenoe and Whitehead (1997), Wu (1998), Hoen (1997) and others confirmed these findings. This contradicts popular assumptions that premarital cohabitation is good for marriage because couples are able to get to know each other better. Neither the divorce rate, nor the illegitimacy rate, nor the single parent family rate alone captures the extent to which children will experience family breakdown and life in a single or no parent household. Of the 67% of children born to married parents in the United States in 1990s, it is estimated that 45% will see their parent divorce by the time they are eighteen10. There is considerable scientific evidence that the psychological damage done by voluntary breakup of the family is greater than the involuntary breakup caused by death11. Based on all these facts, we can clearly conclude that the nuclear family has weakened across the board over the past forty years, and that the functions that these broken families still perform, like reproduction, are not being performed well. This has an evident impact on human capital and in the economy as a whole, since the family is both the source and transmitter of human capital and economic activity. Analyzing the Causes At least four arguments have been proposed to explain why the economic developments 8 of the past 40 years have been accompanied by the breakdown of the family. Some point to the increase of poverty and/or the increase of income inequality. Others blame its opposite, i.e. the increase in wealth as its cause. Another group charges the welfare state. Finally others see the cause not in economic variables, but in a broad change in society brought about by a decline in religion, and the promotion of individualistic self-gratification over community obligations. It is a well-documented fact that there is a strong correlation between broken families, poverty, crime, distrust, drug use, low educational performance, and low human capital. Disagreements arise over causalities. Empirical evidence, however, suggest that the causality does not go from economics to the family but vice versa12. Today societies are much wealthier than in previous decades and yet they are more unequal13. In addition, the povertization of women in most cases is linked to divorce or single motherhood, and not to discrimination, as radical feminists have claimed in the past. Figure 2 shows that in the U.S. married women, independent of their ethnic background, are better off than single mothers. It is true however, that the European countries which have various family support and income maintenance programs in place, show a less damaging povertization of women as a consequence of family breakdown. This indicates the effectiveness of these programs to lighten the effect of povertization of women and children, but have yet to solve the social problems that the breakdown of the family brings14. These programs managed to shift parental responsibilities to individual taxpayers, consumers, and the unemployed. This past year countries such as Great Britain, France and Germany have started to actively seek solutions to the family instability prevalent in these countries. In the Green Paper for example, it is stated that “the government thinks that the defense of marriage and the family will end the illnesses present in British Society. In particular, it hopes to reduce the divorce rate – four of every ten marriages- the high proportion of illegitimate births (34% in 1995), and the damage that divorce causes in the children of divorced couples.” This seems to suggest that developed countries have come to the realization that the breakdown of the family has more than public finance effects in their country15, and empirical evidence supports this realization16. 9 Figure 2 Percentage of Women who are in Poverty by Family Structure and Ethnicity 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 67 58 43 29 14 9 Married Single Married White Single Black Married Single Hispanic Sources: Research and Statistics on Children and Families, Annual Report 1997. Child Trends Inc. The argument that growing individualism and the social problems resulting from it are the consequence of prosperity is on its surface much more plausible than the opposite argument. Family breakdown and crime increased over an extended period of time during which the wealth of developed countries increased steadily. Moreover, there is a broad correlation between value change and income levels within the OECD were wealthier nations have higher levels of family disruption than poorer countries such as Portugal and Spain17. It makes sense to think that as income levels rise, the bonds of interdependence that tie people together in families and communities will weaken, because they are now better able to get along without one another. But although there is a great deal of truth in this train of thought, the answer is neither completely satisfactory nor is there enough empirical evidence supporting this position. If anything, evidence points to a different direction. Those most afflicted by the breakdown of the family and high levels of crime tend to be the least wealthy members of society18. Not much support is found regarding the charges being made against the influence of the welfare state on the family either. Developed countries show no positive correlation between levels of welfare benefits and family stability. Indeed, there is a weak correlation –never mind causality- between high-welfare level benefits and illegitimacy, which tend to support the 10 argument that the welfare state is not the cure for family breakdown. Furthermore, the highest levels of illegitimacy are found in the Scandinavian countries of Sweden and Denmark, where redistribution of income is quite high due to their socialist economic structure. In the face of such a social problem coupled with an aging population, it is not an accident that European welfare states have run into serious economic problems in the 1990s, producing high levels of unemployment and financial instability. Those who have set the responsibility for family breakdown in mistaken government policies maintain that perverse incentives created by the welfare state itself explain present family problems. For example, the Aid to Families with Dependent Children, the primary American welfare program targeted at poor women, provided welfare programs only to single mothers and thereby penalized women who married the fathers of their children19. Similarly, Alm et al (1999) show that the present tax structure in the U.S. penalizes married couples more than cohabiting couples. The percentage of penalty to pre-tax income is between 4.5% and 10.1% higher for the first group. Also the rising rate of crime is seen as the result of the weakening of criminal sanctions that have also occurred over the past forty years20. The empirical evidence supporting this position is not very conclusive, however. While it is true that the percentage of illegitimate children is higher in countries where the welfare state is far reaching, as is the case in Europe, and low where benefits are low as in the case of Japan, United States and other developed countries. Yet, this last group does not show the same behavior. In fact, econometric studies indicate that while welfare benefits have stabilized and even deteriorated in real terms during the 1980s in some countries, family breakdown has continued increasing through the 1990s21. In addition, it has to be taken into account that illegitimacy is only one of the elements in the weakening of the family. Others include divorce, declining fertility, and cohabitation, all of which are more prevalent among middle and upper class individuals. Working Women In the past three decades, many have declared that with the advent of two-income families 11 the work of the home is something of the past22. In fact, housework continues to consume a substantial amount of time for working mothers. While estimates vary widely depending on the sample examined and on the methods used to generate this information, housework time ranges from 20-30 hours of work at home in addition to a full time job23. A growing awareness has arisen of the presence of women in the work place along with the consequences that this presence has on the parental obligations shared by both men and women. Among the problems germane to this issue, two have been a matter of particular concern: the problem of supervision for children both below school-age, and school-age children who are dismissed from school before their parents finish work (‘latchkey children’), and also the difficulty of employer retention of valuable working women. It is clear that the family as an institution exists to give legal protection to the motherchild unit and to ensure that adequate economic resources are passed from the parents to allow the children to grow up to be viable adults. Fukuyama (1999) proposes two causes that contribute to the breakdown of the family. First, the development of contraceptives, and second the movement of women into the paid labor force. It is important to note that the significance of contraceptives cannot be reduced to the decline in fertility. Fertility had already fallen in some societies before the pill’s invention. In addition, an explosion in illegitimacy and a rise in the rate of abortions have accompanied the spread of contraceptives since the 1970s24. Both facts tend to suggest that contraceptives have effects other than the decline of fertility; it also influences the stability of the relationship between men and women within marriage and outside marriage by encouraging promiscuity25. In recent years, the rise of females’ income has also been related to the breakdown of the family26. The assumption behind this relationship is that many marriage contracts are entered into with imperfect information: husbands and wives discover that once married, life is not a perpetual honeymoon, and that their spouse's behavior changes from what it was before marriage. As some economists suggest, trading one husband for another when they have discovered this reality was impossible for women before because they depended on their husbands economically. As female earning began to rise however, women became better able to support themselves and to raise children without husbands. At the same time these economists argue that rising female 12 income also increases the opportunity cost of having children and therefore lowers fertility27. Fewer children mean less of what Becker characterizes as joint capital in the marriage, and hence makes divorce more likely28. It is not clear however that working women who divorce follow this rationale necessarily. Perhaps it might apply to those cases where the parties enter marriage for its pleasures. Another plausible reason is the fact that the entering of women into the labor force puts on them an additional burden when it comes to meeting the needs of both work and family. It is empirically proven that the work structure is male oriented and that it does not provide the flexibility that mothers of families need to meet their family obligations. Therefore, their work becomes a source of tension in the marital relationship and it affects their work performance as well as the care of their husband and children. Empirical evidence links higher female earnings to both divorce and extramarital childbearing29. Figures 3 and 4 plot divorce versus female participation in the labor force and female participation in the labor force respectively. The first graph supports a positive relationship between divorce and female participation in the labor force in most cases. Japan and Italy have both low females labor participation and low divorce rates. On the other extreme we find the United States, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. Notwithstanding, in a study on divorce undertaken by Sullerot (1997), she reports that in Europe of the number of divorces initiated by women, between 33% and 75% suffered a significant decline in their income. This is consistent with the povertization of women in the last forty years, which was mentioned before and shown in figure 2. The second graph shows an increase of female participation since the 1970s. The rate at which the increase participation has taken place however, has leveled out since 1990. A recent study of the Families and Work Institute (1995) reports that in the US, women 's income is becoming necessary for the sustenance of the family. Women contribute at least 45% of the family income of married parents. The contribution is even higher in single parent households, mainly headed by women, where their contribution is of 90% or more30. The study also reports 13 Figure 3 Divorce Rate Divorce versus Female Labor Force Participations 5 4.5 4 3.5 3 2.5 2 1.5 1 0.5 0 United States UK Australia Sweden Netherlands Germany Italy Japan 0 10 20 30 France 40 50 60 70 Female Labor Force Participation Sources: International Labor Organization Figure 4 Percent Female Participation, Ages 20-39, 1950-2000 100 90 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 Japan Sweden UK United States 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 Year 1995 2000 Sources: International Labor Organization that only 15% of all women would like to work full time was even if this was not necessary to maintain the family, 33% would like to work part-time; and 31% would prefer not to work outside their homes. Therefore it is not surprising that in more recent years we have seen an 14 explosion of innovations in this front, ranging from flextime working hours to job-sharing positions, or companies that professional women support so they are able to work from their homes31. So far, the solutions proposed to meet parental responsibilities regarding supervision have included child care oriented policies and income tax credits at the governmental level. Private initiatives such as a system of flexible working hours and more recently, on-site day-care or other childcare support provided by employers have been developed32. As was previously mentioned, governments, especially in Europe, are introducing more incentives for women to continue working while having a family. Developed countries are now concerned not only with the effect on children and the family, but also with their current low fertility rates. 2. Children and the importance of human Capital There is a strong relationship between family and human capital. Families constitute the most basic cooperative social unit, one in which husband and wife meet to work together to socialize, to beget, and to educate their children. The family in the past typically educated its children at home, took care of the elderly, and in view of the physical isolation and/or lack of transportation as it occurred with families working in farms for instance, was also its own main source of entertainment. Today, these functions have been separated from the family. As men and women started working outside the home, children were sent to public schools for education; grandparents moved to retirement or nursing homes; and entertainment was provided by TV and other means of mass communication. The movements of these functions outside the family unit has had a deleterious effect seen most markedly when reproduction was separated from marriage. A growing concern of the past decade has been a decline in the academic performance of American students at large who have done poorly on standardized tests compared with their peers abroad, especially in Asia. On average, American students read less, have weaker analytical skills, a declining command of their language, and in general are less well rounded. They tend to watch more television and videos, and spend more time playing computers games than their peers in other countries do33. Faced with this reality, several studies have sought causes and solutions to these growing educational problems. Both school and family input as well as social 15 conditions are relevant in this area. The 1966 Coleman report commissioned by the U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare, found that after controlling for family background in student achievement, there is little evidence that the level of school resources has a statistically significant effect on student test scores34. Furthermore, the report emphasized that family and peers have a much greater impact on educational outcomes than the inputs over which public policy has control. Lack of parental support and involvement, as well as the absence of early stimulation, together with the breakdown of the family structure have been found to be important factors affecting children’s performances35. Empirical evidence on the impact of school resources on student outcomes continues to be ambiguous. Divorce, out-of-wedlock birth, and single-parenthood are shown to be very detrimental to the affected children's development. Children that come from broken families or raised by single mothers tend to have more problems related to drug abuse, alcoholism, violence, and academic performance. They also have more health problems, depression, and higher suicide rates than those proceeding from stable families. These results are independent of the income level of these children, thus suggesting that income is not the major variable in children’s development health36. Blum (1997) has shown that the closer the relationship and the trust between parents and children, the better is their academic performance and the lower is the risk of their getting involved in unhealthy activities. Finally, studies show that it is important that parents be present at key times during the day, for instance after school and at dinnertime37. Not only parents, but employees and society as a whole are concerned with a widespread lack of child supervision that result in poor academic performance, as well as the needs of working parents. In a 1994 study, the Carnegie Foundation reported that in the U.S. the breakup of the family is primarily responsible for poor childcare. Almost 40% of children under three years old live with one parent, more than 50% of women with children under one year work full time outside the home – in most cases due to economic needs- and are either single mothers or divorced. Malkin and Lamb (1994) report that child abuse in single parents’ homes is four times higher than child abuse in households with both parents. This risk increases to six folds for children living in cohabitational households. Childcare has shown to be a solution with many risks, at least for the United States. A 16 study of the National Institute of Child Health and Development reported last year that 80% of children under one year, are habitually supervised by an adult other than the mother for at least thirty hours a week. The same report points out that child care facilities do not provide the quality of service required by the child to develop well, and between 15-20% of these services are detrimental to children. In response to this report, the US government created a committee of private businesses to seek solutions to these problems. The conclusions of their study were that “policies that favor the family were profitable for business.” Johnson & Johnson reported that for every dollar allocated to subsidize maternal leave or childcare, it was earning $4 in increased productivity. Eli Lilly, reported that granting leave of absence to parents to take care of children’s needs or family illnesses was facilitating the motivation and retention of more dedicated, innovative, and productive workers. The same parental support is not found in small or mid size business. On the contrary, workers that try to attend to the needs of their children often find their promotion is jeopardized38. The development of human capital requires close involvement of parents, especially during the child's early years. This has been overlooked until recently by the information society and consequently it has imposed additional social costs to society as a whole and has hampered economic development. The introduction of innovative ways to facilitate making family responsibilities compatible with work outside the home has increased worker performance, productivity and profitability. 3. A side effect with great risks: An Aging Society Human capital, as was previously mentioned, could not exist without people. The generation that grew during the 1960s and 1970s continually heard of the population explosion and the global environmental crisis. By the 1980s all developed countries had undergone a demographic transition in which the total fertility rate (average number of children per women per lifetime) fell below replacement levels. The decline in fertility follows an aging society. A growing proportion of the retired to active population characterizes an aging society. Unlike other issues such as the effects of population growth on the environment or resources, there can be little debate over if or when an 17 aging population will manifest itself. These predictions are not based on hypotheses but on facts. This is the case for two reasons: First the population we are referring to are living people who are already here, and whose average life expectancy has increased between 1950 and today from 46 to 66 years old today in less developed countries and to 70 in developed countries39. The second reason is that the increase of life expectancy is happening while there is a reduction in the number of young people because of the fall in fertility rates. The UN defines an aging society as having 7% or more of the population at 65+ years. From 2000 to 2025, the number of people above 65 will double while the number of youngsters under 15 will increase by 6% only. The reversal of the age pyramid affects virtually all societies today, and more markedly affects the industrialized countries. In Europe it is estimated that by 2025, 31.2% of the population will be 65+. In addition, the dependency ratio (typically defined as the percentage of the population aged 65+ over the percentage of the population aged 15-64) is expected to increase from an average of 50% in 1995, to an average of 85%-90% by the year 2050. The causes of the aging of population are complex. Some factors are found in the living conditions and socio-cultural changes which countries have faced in the past 30 years. The infant mortality rate has decreased while the fertility rate (the number of children born to each woman) has fallen below the replacement levels of 1.7 - 1 in the EU and East Asian countries. Moreover, the marriage rate has declined in an environment that is hostile to matrimony; this is coupled with a sharp increase in the mean age at which women first give birth. This phenomenon is exacerbated by labor codes that do not facilitate women's desire to harmoniously integrate their family life and professional activity. Some developed countries are trying to reverse the trend in fertility rates by implementing policies that facilitate child-bearing through flexible hours arrangements, work sharing, and alternative leaves of absence. These symptoms suggest that the lack of supportive family policies in the past decades have not allowed families to have the number of children they prefer. Another important factor, especially in developed economies, is the widespread belief that keeping a certain quality of life is more important than having several children. People assume that population control is a necessary antecedent to development. Ben Wattenberg, in his book The Birth Dearth, has observed that "in the wealthiest age of history many youth say that 18 they cannot afford to have more than two children." Such a rationale holds that if there are fewer children, better investments can be made for each one and greater savings will take place, thus leading to an overall increase in the standard of living. Ironically, studies show that despite the higher standard of living, wealthier populations experience a greater amount of pessimism. In an age of many comforts, depression and a general loss of a sense of meaning in life (remarkably manifested by youth violence and suicide) have increased. Despite the sharp fall in fertility rates, overall savings are very low, and in those countries where savings are positive, it tends to be highly concentrated. Many economists contend that private saving rates are affected by a society's age structure, mirroring the change in an individual's saving rate over the life cycle. This being the case, in an aging population context one can expect even a greater deterioration of national saving rates. Heller (1997) estimates that by 2010, Europe and East Asia will experience a near 10% decline of their GDP and 13% decline by 2025. These numbers, however, are sensitive to the econometric estimates used and should be taken as lower bounds; in fact, the deterioration might be greater. In the face of this reality, governments and international organizations have become concerned because implosion and the consequent aging population have serious consequences for countries. One of the clearly predictable burdens will be presented by social security systems. A smaller population will need to support an aging population that is less active and has a greater need of healthcare and medical services. If one adds to this the fact that most social security systems are predominantly of the pay-as-you-go type, the absence of younger generations endangers the possibility of supporting the older population. Many of the solutions proposed include tax increases of different forms. Other solutions advanced include radical reforms of the retirement benefit systems such as tight limits on public health spending, modest pension benefits formulas, and new personally owned savings programs that allow future public benefits to shrink as a share of average wages. Of course, this requires that governments undertake serious budgetary adjustments and find solutions that might not be optimal to meet the needs of the elderly. However, there are other issues related to meeting the needs of the elderly. Heller points out that "there are other concomitant effects of epidemiological developments, changes in prevailing medical technologies, upgrading of 19 educational systems, and social pressures to provide broader social safety net coverage for elderly persons living outside the formal urban sector. Each of these developments may result in important national policy developments (...) [which] will create significant fiscal pressures. Furthermore, the security of elderly retirement becomes ever more necessary as traditional extended family support systems weaken.40" Often overlooked are other economic burdens, such as the effect on the education of youth and the competition between the younger and older people as the latter try to protect their jobs while younger generations enter into reduced job markets. At times, people are forced to retire from active employment, while they still have great inner resources and are still able to contribute to the common good. Initially, the increase of early retirement as well as the reduction of young people forming the labor force can seem to alleviate unemployment - especially in European countries where unemployment has become a chronic problem. Later on, the reduction of the labor force favors immigration. In fact, immigration has increased. It is calculated that about 120 million persons -about 2% of the world's population- have emigrated to other countries. An increase of urbanization is also expected. Since 1967, the number of people that live in urban areas has increased by 40%, but this urbanization is often not accompanied by the expansion of infrastructures needed, thus opening the way to poor and ill-equipped living conditions. In the area of education, one can predict another conflict. In order to provide for the economic needs of the elderly, there is a great temptation to cut down on money allocated for the training of new generations. Consequently, the transmission of cultural, scientific, technical, artistic, moral and religious goods is endangered. This poses the danger of "moroseness," that is, the lack of intellectual, economic, scientific, and social dynamism with the attendant reduction of creativity. Population growth expands the market and facilitates creativity and dynamism. Thus an important question arises as to whether it is possible to maintain economic growth with implosion. Some economists argue that economic growth can be sustained even under a declining population, if it is supported by an endogenously induced technological progress in the market (i.e., if tightening labor-market conditions stimulate better utilization of resources.) The rationale is that accumulation of human capital and decline in the labor force 20 would raise real wages faster than societies are aging. It would also increase the return from utilizing human capital and would thereby stimulate innovation. This line of argument ignores precisely the last two problems mentioned. Thus, Malthus and his followers are mistaken on both the demand and the supply side: on the demand side, because population does not follow a geometric growth as Malthus predicted and on the supply side, because the resources are not easily extinguished since they are created and expanded by the people who are born, live, and work. In summary, population growth expands markets and facilitates creativity and dynamism. It is impossible to maintain economic growth with population implosion and the need to support an aging population. Population control policies more than facilitating economic development hampers it in several ways. It weakens the family structure, which in turn leads to the povertization of women and children as well as to the reduction of human capital. Both of these elements are essential for a lasting real economic development. It also inverts the population pyramid leading to an aging population problem and to the countries' public finances burden that follows. IV. Towards the Protection of the Family: An Economic Sound Choice The breakdown of the family social cost has been very high. Figure 5 shows social welfare cost as a percentage of GDP between 1972 and 1998 of major developed countries. It is clear that for all countries, the family breakdown has been accompanied by a significantly increase of social welfare costs during the 1970s which continued until 1992. At this time, the social welfare cost rate of growth slowed down with the exception of Germany. The anomaly observed in 1992 for this country, corresponds to its unification and thus is not very significant. It is interesting to consider that the combination of social security plus family and health welfare expenditures for developed countries were on the order of $1,216 billion dollars for the US, $354 billion for France, $258 billion for the UK, and $266 billion for Germany in 1996. These numbers are bigger than any of the less developed countries foreign debt. For example, US expenditures are seven times the debt of Brazil, the largest debtor, and in 1996 it was 20% bigger than Brazil's GDP. By contrast, if we take Nigeria as an example of a Sub-Sahara country, we 21 Figure 5 Social Welfare Government Expenditures 35 Social Government Expenditure/GDP 30 25 20 15 10 5 US Germany 1980 1989 France UK Sweden 0 1972 1992 1995 Year 1996 1997 1998 Sources: World Development Report, 1991, 1994, and 1998. The World Bank find that US social welfare expenditures in 1996 were 40 times Nigeria's foreign debt and about 10 times its GDP. Even UK social welfare expenditures, which are the lowest of all the countries included in figure 5, were 8.6 times Nigeria's debt and double its GDP for the same year. These numbers underlined why it is very important for developing countries to protect its family and its population. Their present economic situation does not allow for the same mistakes that developed countries made and now are trying to repair. If these countries are to experience real economic growth, both their family and their population ought to be protected from its breakdown and its implosion respectively. Developed countries seem to be realizing the consequences that the breakdown of the family has had in their society. Therefore they are seeking out policies that will help reverse this trend. They seem to know that redistribution of income towards the victims of such disruption is not enough. Great Britain for example, in the report entitled Supporting Families, has advanced a proposal to create an Institute for Family and Parenthood to advise parents in matters regarding the education of children. It also proposes the elimination of 24 hour-noticed civil marriages and the introduction of preparatory classes so as to encourage couples to become aware of their right and duties in marriage. France in the last year has also shown a significant shift in family policies, which are directed, to reinforcing family supports. For example and among others, as of 1999, once again 22 all families with at least two children receive family subsidies independently of their income level. The family subsidies had been cut in 1997 for high-income families. It also extends childsupport to parents to 19 years old or 20 if the dependent is a student, and it expands credits and subsidies for family housing. Holland and the United States have introduced as a labor right, parental leave for family needs, thus giving rise to ‘family days’ benefits. The goal is to facilitate parents meeting their family, as well as their work, obligations. Child-care has been the focus of some family policies. The extent of this last benefit varies from country to country. Germany provides 100% coverage while Finland and Sweden cover between 80 and 90%. In summary, we can say that industrialized economies have experience significant increases in welfare cost expenditures as their family institution has undergone a serious crisis. As a consequence new efforts are being taken to reverse this effect and reinforce this basic unit of society. V. Conclusion A family’s consumption needs give rise to economic activity. In educating its children it influences what is produced in the economy. As the members of these families contribute to the economy, private property and other institutions and services such as health services, housing, education, social securities, national security, etc, develop so as to complement and meet the needs of these families. If we are to understand any economic issue the way in which the given issue affects the family as a whole or a given member of it, must be evaluated carefully. For this is directly and indirectly the most important reason for economic activity: the good of the family. We cannot forget that any task carried out for mainly selfish motives (i.e., individualistic) still cannot be obtained without someone else serving that economic agent or institution. In this case "someone" is being used. This utilitarian approach eventually destroys the motivation to work and, thus affects directly or indirectly the family. The disruption of the family has had serious and high social welfare costs for societies, as we have seen occur in developed countries. Furthermore, the size of such costs indicate that were this to happen in less developed countries, these group of countries would not be able to afford them. It would, instead further hamper their efforts to develop. In addition, population 23 control policies as those being implemented in developed countries do not contribute to their real economic development but on the contrary, it contributes to the deterioration of the family. The results therefore suggest by contrast, that when family is considered as a fundamental good and defended, sound economic policy is developed and real economic growth is possible. This is so because a well functioning family is essential for economic activity. It is important at the same time, to keep in mind that macroeconomic policy making (such as health care, taxes, minimum wage, population policies, etc.), although important because of the extent of its impact, is not the only aspect to be considered in economic activity. Policies at state and local levels, such as education programs, sanitation, property taxes, sale taxes, and at the private corporation level, such as maternity leave, stock share, flexible hours, family benefits, etc., are extremely important as well and, many times are more sensitive to individual family decision making. Bibliography Aaron, Henry and Thomas Mann, 1995. Values and Public Policy. Washington DC: Brookings Institution. Aceprensa, 1995. "EE.UU.: el Sueldo de la Mujer, Necesario en Muchas Familia", Aceprensa, 84:95, June 14, 1995. Alm, James, Stacy Dickert-Conlin, and Leslie A. Whittington, 1999. "Policy Watch: The Marriage Penalty", Journal of Economic Perspectives, 13:3, pp. 193-204. Alvarez, Jose Luis, 1996. Barcelona. Empresa y Vida Familiar, Estudios y Ediciones IESE. Spain: Alvira, Rafael, 1987. "Elementos Configuradores de la Familia", in La Familia y el Futuro de Europa. Barcelona: Fundacion Ferran Valls I Taberner. Becker, Gary, 1968. "Crime and Punishment: An Economic Approach", Journal of Political Economy, 11:1. pp. 169-217. __________, 1991. Treatise on the Family. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ___________ and Elisabeth Landes, 1977. "An Economic Analysis of Marital Instability", Journal of Political Economy, 85:4, pp. 1141-1187. 24 Bethke, Jean, 1995. Democracy on Trial. New York: Basic Books. Black, Rebecca M., 1997. "Policy Watch: The 1996 Welfare Reform", Journal of Economic Perspectives, 11:1, pp. 169-177. Blum, Robert, M.D. Resnick, P.S. Bearman, K.E. Bauman, K.M., Harris, J. Jones, J. Tabor, T. Beuhring, R.E. Sieving, M. Shew, M. Ireland, L.H. Bearinger, and J.R., Udry, 1997. "Protecting Adolescencts from Harm. Findings from the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health", Journal of the American Medical, 278:10, pp. 823-832. Bumpass, Larry and James A. Sweet, 1986. "National Estimates of Cohabitation", Demography, 26:3, 1986. Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, 1994. International Schooling Project. Menlo Park: Carnegie Foundation. Coleman, J.S., E.Q. Campbell, C.J. Hobson, J. McPartland, J. Mood, S.M. Weinfeld, and R.D. York, 1966. Coleman Report: Equity of Educational Opportunities, Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. Datcher-Loury, Lori, 1988. "The Effects of Mother' Home Time on Children's Schooling", Review of economics and Statistics, 70:3, pp. 367-73. Ehrenreich , Barbara, 1993. “Housework is Obsolete”, Time, October 10. Economist, 1998. "Two Against the Clock", The Economist, 19-VII-1998. Farley, Raynolds, 1995. State of the Union: America in the 1990s, vol.2, Social Trends. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. Friedan, Betty, 1963. The Feminine Mystique. New York: Dell Publishing Company. Fuerst, J.S. and R. Petty, 1996. "The Best Use of Federal Funds for Early Childhood Education", Phi Delta Kappa, June, pp. 676-681. Fukuyama, Francis, 1999. The Great Disruption. New York: The Free Press. Garasky, S., 1995. "The Effects of Family Structure on Educational Attainment: Do the Effects Vary by the Age of the Child?, American Journal of Economics, 54:1, pp. 89-105. Green, Germaine, 1989. Daddy We Hardly Knew You. New York: Knof. __________, 1991. The Female Eunuch. New York: McGraw Hill. Grissmer, D.W., S.N. Kirby, M. Berends, and S. Williamson, 1994. Student Achievement and 25 the Changing American Family. Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corporation. Halcrow, Allan, 1986. “Child Care: The Latchkey Option”, Personnel Journal, pp. 12-13. Hanushek, E.A., 1986. "The Economics of Schooling: Production and Efficiency in Public Schools", Journal of Economic Literature, 24:3, pp. 1147-1177. Hedges, L.V., R. Line, and R. Greenwald, 1994. "Does Money Matter? A Meta-Analysis of Studies of the Effects of Different School Inputs on Student Outcomes", Educational Research, 23:3, pp. 5-14. Heller, Peter, 1997. Aging in the Asian Tigers: Challenges for Fiscal Policy. Occasional Paper Series. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund. Hoen, Jan M., 1997. "Cohabitation in Sweden", Vlfrdsbulletinen, 89:2, pp. 435-467. Jones, Elise F., 1986. Teenage Pregnancy in Industrialized Countries. Connecticut: Yale University Press. New Haven, Lundberg, Shelly and Robert Pollakm, 1996. "Bargaining and Distribution in Marriage", Journal of Economic Perspective, 10:4, pp. 139-158. Malkin, Catherine and Michael lamb, 1994. "Child Maltreatment: A test of Sociobiological Theory", Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 25:1, pp. 121-133. Malthus, Thomas R., 1824. "A Summary View of the Principle of Population", Encyclopedia Britannica. Marler, Janet H. and Cathy Enz, 1993. “Child-Care Programs that Make Sense”, The Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, 34:1, pp. 60-68. McLanahan, Sara and Sanderfur, Gary, Growing Up with a Single Parent: What Hurts, What Helps. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1994. Moffitt, Robert, 1990. "The Effects of United States Welfare System on Marital Status", Journal of Public Economics, 41:1, pp. 101-124. Murray, Charles, 1993. "Welfare and the Family: The United States Experience", Journal of Labor Economics, 30:1, pp. 1-61. National Institute of Child Health and Development (NICHD), 1999. "Child Outcomes when Child Care Center Classes Meet Recommended Standards for Quality. NICHD Early Child Care Research Network", American Journal of Public Health, 89:7, pp. 1072-1077. Popenoe, David, 1996. Life Without a Father: Compelling New Evidence that Fatherhood and 26 marriage are Indispensable for the Good of Children and Society. New York: Free Press. ________ and Barbara Dafoe Whitehead, 1997. Should We Live Together? What Young Adults Need to Know about Cohabitation before Marriage, National Marriage Project, New Jersey: Rutgers University. Putman, Robert D., "Turning in, Turning Out: The Strange Disappearance of Social Capital in America", Political Science and Politics, 1995, 664-682. Rosenzweig, Mark and Keeneth Wolpin, 1994. "Parental and public Transfers to Young Women and Their Children", American Economic Review, 84:3, pp. 1195-1212. Schwartz, Antonio and Gail Stevenson, 1990. Public Expenditures Reviews for Education. DC: The World Bank. Sullerot, 1997. Le Grand Remue-Mnage: La Crise de la Famille. Paris: Fayard. UNFPA, 1999. 6 Tousand Million. New York: United Nations Fund for Population Activities (UNFPA). _______, 1998. 1998 Human Development Report. New York: UNFPA. U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1998. Statistical Abstract of the United Sates. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office. U.S. Department of Education, 1994. The Condition of Education. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics. U.S. Department of Education, 1996. Reading Literacy in the United States: Findings from the IEA reading Literacy Study. , Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1995. Report to Congress on Out-of-Wedlock Childbearing, Hyattsville, MD: U.S. Government Printing Office. Waldfogel, Jane, 1998. "Understanding the Family Gap in Pay for Women with Children", Journal of Economic Perspective, 12:1, pp. 137-156. Wallerstein, Judith, 1993. Second Chances: Men, Women and Children a Decade after Divorce. New York: Basic Books. Wattenberg, Ben, 1989. The Birth Dearth. New York: Pharos Books. Wolff, Edward, 1998. "Recent Trends in the Size Distribution of Household Wealth", Journal of Economic Perspectives, 12:3, pp. 131-150. 27 Wu, Zheng, 1998. Economic Circumstances and the Stability of Nonmarital Cohabitation. Otawa: Survey of Labour and Income Dynamics, Statistic Canada. ENDNOTES 1. Fukuyama (1999), p.4. 2 . Becker (1991), p. 55. 3 . These numbers have been obtained from the Economic Report of the President of 1999 and Handbook of International Economic Statistics of 1991 and 1998. 4 . Statistical Abstract of the United Sates (1998). 5. Ibid. 3. 6. ibid 3. 7. McLanahan and Sanderfur (1994). 8. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (1995). 9. Jones (1986). 10. McLanahan and Sanderfur (1994). 11. Wallerstein (1993) and Popenoe, (1996) provide a review and analysis of this evidence. 12 . See Putman (1995), Garasky (1995), and Grissmer et all (1994) for views on this matter. 13 . See Wolff (1998). 14 . Farley (1995) presents detailed data. 15 . This realization varies from country to country however. Some countries such as Australia, do not refer to marriage per see, but to the stability of couples in general, others make clear the differentiation between marriage and other unions, supporting clearly the first one. I am grateful to Wade Horn for bringing this point to my attention. 16 . See Fukuyama (1999) for an analysis and review of the literature on this subject. 17 . See Aaron and Mann (1994) for a review of this position and some empirical support. 18 . Rosenzweig and Wolpin (1994). 19 . For a description of the welfare reform measure see Black (1996). 20 . See Becker (1997). 21 . Murray (1993) and Moffitt (1990) present interesting evidence. 22 . Ehrenreich(1993), Friedan (1963), and Green (1989) are some examples of this position. 23 . Waldfogel (1998). 24 . U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (1995), p.72. 25 . It is interesting to notice that the very same Malthus had warned of this danger. In his 1824 essay he states: "Moral restraint, in application to the present subject, may be defined to be abstinence from marriage, either for a time or permanently, from prudential considerations, with a strictly moral conduct towards sex in the interval. And this is the only mode of keeping population on a level with the means of subsistence which is perfectly consistent with virtue and happiness. All other checks, whether of the preventive or the positive kind, though they greatly vary in degree, resolve themselves into some form of vice or misery. (p.38)" 26 . Becker (1991). 27 . For an example of this view see the early works of Becker and Lundberg and Pollak (1996). 28 . Becher (1991). 29 . Becker and Landes (1977). 30 . Aceprensa (1995). 31 . Alvarez (1996) points out five key areas that firms need to address to help women overcome the tension between family and professional life. These are: a. Maternity leaves and benefits. b. Flexibility, which will allow to address varied family circumstances which often contrast the rigidity of the corporate organization. Most corporate jobs are set in terms of fixed schedules and place of work. A mother of a family often needs flexibility in these two fronts. c. Other family supports such as childcare, elderly assistance, moving expenses, direct or indirect subsidies for housing, etc. d. Alternative models to the linear professional carrier and e. Mentoring in the area of professional development. 28 32 . See Halcrow (1986) and Marler and Enz (1993) for more details on these initiatives. . Schwartz and Stevenson (1990). 34 . After this report, a debate originated. As the original Coleman report noted, if researches do not control for family background, then, when analyzing a data set in which children from wealthier families attend schools with smaller class size and better-paid teachers, the results will find a positive correlation between student outcomes and school resources. But this correlation might simply mean that students from better families are primed to do better in school. Conversely, the extent to which students from poor families are more likely to be assigned to remedial schools with higher resources per students supports the result that, with greater school resources, reduced students outcomes will be found. A good review of the first debate is contained in Hanushek (1986). Hedges, Line, Greenwald (1994), Datcher-Loury (1988), and Card and Krueger (1992) present some reviews of the opposing side of the discussion. 35 . Fuerst and Petty (1996), US Department of Education (1994, 1996), and Grissmer et al (1994) are some studies dealing with these factors. 36 . Bethke (1995). 37 . Blum (1997). 38 . The Economist, 1998. 39. The data has been taken from 6 Tousand Million. Is time to Contribute, a UN Report published with the Occasion of the 6 billion people mark to be celebrated on October 12, 1999 and the 1998 Human Development Report published by the United Nations Fund for Population Activities (UNFPA). 40 . Heller (1997), p. 15. 33 29