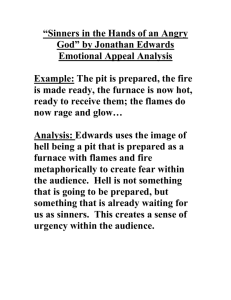

Jonathan Edwards on Sin and Self-Knowledge

advertisement