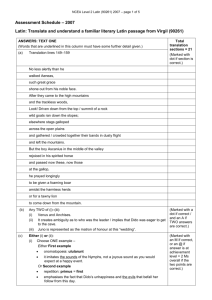

final paper.doc - AP English Language

advertisement

Coleman 1 Elizabeth Coleman Reading Vergil’s Aeneid Dean Santirocco Final Paper 28 April 2005 Pater Aeneas, Filius Ascanius: Fathers and Sons in Relation to Aeneas’ Quest for Pietas in Vergil’s Aeneid In Book VI of Vergil’s Aeneid, Aeneas encounters at least three pairs of fathers and sons: Brutus and his sons, Marcellus the Elder and Younger, and Daedalus and Icarus. The concentration of these three father-son pairs illustrates the importance of parental relationships throughout the Aeneid. Loving father-son relationships play prominent roles in at least eight of the Aeneid’s twelve books.1 However, the central father son relationship, between Aeneas and his son Ascanius, is best described as cold and distant. Aeneas’ relationship with his own son is problematic, particularly in light of these other caring fatherson relationships. However, all of these father-son combinations (including Aeneas’ relationship with his own father Anchises) speak volumes about Aeneas as a father, Ascanius as a son and the correct way to lead the Trojan people. The relationships between Lausus and Mezentius, Evander and Pallas, Aeneas and Pallas and Aeneas and Anchises all reveal facets of Aeneas’ personality and the correct way to rule with pietas. Each father-son relationship in the Aeneid approaches perfection, yet none (including Aeneas’ relationship with his own son) ever achieve the perfect (or at least Vergilian) idea of filial and paternal love. However, a 1 Gotoff 198. Coleman 2 synthesis of the pitfalls and triumphs of each provides a picture of Vergillan perfection and the correct way to both parent and govern. Lausus and Mezentius After watching his father Mezentius be wounded by grief-stricken Aeneas (after the death of Pallas), Lausus first helps his father escape to safety, then faces the Trojan prince himself. When Aeneas sees the clearly inferior Etruscan standing against him, he mocks his opponent, telling him “Your loyalty has tricked you into recklessness.”2 With that, Aeneas stabs Lausus, killing him. Once Mezentius realizes that his son has not only died, but died “both to avenge his father’s wound and to protect him,”3 he himself faces Aeneas, and is slain. However, as his dying request, he asks that his body not be sent back to his people (who will surely mutilate it, because he has been a despotic, impious ruler), but that Aeneas bury his body alongside Lausus’. There are two very important father-son dimensions that should be focused on in examining the deaths of Lausus and Mezentius. The first is Aeneas’ role in the death of both father and son, and the second is Vergil’s characterization of Mezentius (and its parallels to Aeneas’ own role as father). First, it is important to analyze Aeneas’ reaction to Lausus’ bravery in the name of his father. Rather than admire the young man’s courage and praise his piety, Aeneas instead mocks him. By facing Aeneas, Lausus is doing no more than Aeneas himself would do for 2 3 Aeneid X 115 James, 627 Coleman 3 his own father. In fact, when Anchises announces that he will not leave Troy, even though the city is crumbling around him, Aeneas puts himself in harm’s way by attempting to continue to fight.4 Even after Anchises agrees to leave, Aeneas takes his father onto his own back, and carries him safely out of the city: “lifting up my father, I made for the mountains.”5 Though he does not die for his father, his actions are akin to Lausus’ challenge. Gaskin is correct in questioning if “Aeneas suggests that Lausus is being deceived by his filial piety… what sort of concept of pietas is that?”6 In fact, in his rage Aeneas seems to have lost all sense of pietas. Earlier, he refused to acknowledge the pleas of Magus, which appeal to his sense of both filial and paternal bonds. Vergil makes sure that “the last words spoken before Lausus dies are Aeneas’ taunts about his pietas overruling his martial inadequacy,”7 and we must assume that he does so for a reason. The reason is simple: after the death of Pallas, Aeneas is temporarily unconcerned with pietas. Instead, he is overcome by furor, and because of this, kills both Lausus and Mezentius. The loss of Pallas, who had been left in his care by King Evander, is felt strongly by pater Aeneas, and it causes him to lose his control and reason.8 Thus, Aeneas’ rage at Lausus and Mezentius, particularly the taunting of Lausus’ filial pietas are caused by the loss Aeneas feels after the death of Pallas, and the failure to fulfill his surrogate paternal duties. 4 Aeneid, II 908-910. Ibid, II 1082. 6 Gaskin, 300. 7 James, 633. 8 Aeneas’ paternal connection to Pallas, and his subsequent furor because of it are later seen in his attack of Turnus in the final lines of the poem. It can be argued that the death of Turnus is merely a symptom of the same grief-stricken rage that causes the deaths of Lausus and Mezentius, just later in the poem. 5 Coleman 4 The other important facet of the Lausus and Mezentius plot is the connection drawn between Mezentius and Aeneas. In the traditional telling of the story of Mezentius, it is not just Mezentius and his son who come to Turnus’ aid, but Mezentius and an entire army. However, Vergil makes sure to characterize his Mezentius as an exile like Aeneas, unable to return to his homeland.9 Here, Vergil sets up Mezentius as a sort of shadow Aeneas. However, there are important difference between the Trojan and the Etruscan. For instance, while both are portrayed as fierce, powerful warriors, Mezentius, unlike Aeneas “has learned too late that the element of responsibility to others interferes with heroic independence.” 10 Until Lausus’ death, Mezentius was entirely unconcerned with his son’s well-being, or with the consequences of his actions beyond his own personal glory.11 After Lausus’ death, however, Mezentius realizes that “his mistreatment of his subjects and his consequent exile reflected upon his son.”12 Suddenly consumed with the guilt, he attacks Aeneas, and, after his death, asks the Trojan prince to bury his body with his sons. Mezentius proves by the end of his life that he has “learned the meaning of parental pietas.”13 By linking Aeneas so closely with the deaths of this father and son pair, Vergil is once again commenting on the Trojan himself. Mezentius is a counter-Aeneas figure in this scene. Like Aeneas, he is an exiled, isolated warrior. At the very end of his life, Mezentius learns the importance of the love a father can have for a son. The question is, has Aeneas? However, Mezentius’ relationship with Lausus is devoid of any real emotional feeling, even at the moment of Mezentius’ death. While he certainly does repent and wish he had 9 Gotoff, 196. Ibid, 205. 11 Ibid. 12 Ibid, 202. 13 Ibid, 207. 10 Coleman 5 been a better father towards Lausus, Mezentius “is still the warrior, magnificent in pride and courage, who will neither give nor take quarter in any battle.”14 For Mezentius, the death of Lausus is something to be mourned, but only in so far as it diminishes his own prowess on the battlefield dishonors him. Nowhere in his final speeches (either to his horse, or to Aeneas) does Mezentius seem concerned that he will never see his son again, but instead that his pride has been wounded (vis a vi the death of his son), and he must avenge it. Mezentius and Lausus show Aeneas (and the reader) the perils of ignoring one’s son (or father) and concentrating only on one’s personal glory. Mezentius ignores Lausus’ wellbeing and inheritance and well-being until he is dead, and Aeneas must be sure not to make the same mistake. And he doesn’t. From the very beginning of the poem, Aeneas is consumed with young Ascanius’ destiny, and is willing to do anything to help his son achieve that destiny, but the deaths of Lausus and Mezentius present a clear picture of the tragedy that could befall Aeneas if he loses sight of Ascanius and begins to focus too narrowly on himself and his personal glory. Pallas and Evander Unlike Mezentius, the Arcadian king Evander realizes the importance of paternal pietas from the first time Vergil mentions him. When Aeneas approaches Evander and asks for his aid in fighting Turnus and the Latins, the king realizes that he is too old and feeble to aid the Trojans productively. Instead, after Evander “takes up the hand of his departing son 14 Ibid, 206. Coleman 6 and clings with endless tears,”15 he sends his son Pallas to fight beside Aeneas. Before Pallas leaves, Evander prays that his son is returned safely, and if Pallas cannot return, Evander wishes that he will die at that moment, rather than witness the death of his son: “ But Fortune, if you threaten my son with the unspeakable, then now, oh, now let me break off this cruel life, while fear is still uncertain and my hope cannot read the future.”16 However, Evander’s prayers go unanswered. Pallas is killed by Turnus on the battlefield. In fact, Pallas’ death “is designed explicitly to punish Evander,”17 because Turnus considers Evander’s reaction when he receives the body of his dead son. When Evander receives the news, he goes immediately to his son’s funeral bier and he “falls on Pallas, clinging and weeping and keening; he can hardly force passage through his sorrow for his voice.”18 Evander is heartbroken over the death of his son, but he remains confident that Aeneas will defeat Turnus and avenge Pallas’ death. In this father-son combination, both Pallas and Evander are outstanding examples of both filial and paternal pietas. As the perfect father figure, Evander, unlike Mezentius, shows concern for and devotion towards his son. Evander is not only concerned about Pallas’ wellbeing, he is devastated at the mere thought of losing his son. However, Evander realizes that Pallas must become his own person and his own leader, and allows his son to travel with Aeneas. Evander could have very easily sent only troops with Aeneas and kept his son home, 15 Aeneid VIII 725-726. Ibid, 752-756. 17 James, 629. 18 Aeneid XI 195-197 16 Coleman 7 however he acknowledges that Pallas must one day rule the Arcadians as well, and so lets him go.19 Pallas, too, shows true filial devotion towards his father. Pallas is initially dueling with Lausus, however, when he realizes that Turnus is about to attack him, he sends up a prayer to Hercules, but notably, in the name of his father: “Hercules, I pray to you by my father’s welcome to you, the board that you, a stranger, shared with him, to help my great attempt! Let dying Turnus see me strip off his bloody weapons, let his dying eyes see me a conqueror.”20 In the moments before his death, Pallas returns to his father, and his father’s former acts of pietas (by housing and showing hospitality towards Hercules) to save him. However, Pallas is not entirely perfect. Although he acknowledges that he is outmatched by Turnus, he “is the first o move ahead, to see if chance can help his daring try.”21 Pallas is still a young man, and he is still eager for the glory that war can provide. He knows that he stands little chance of defeating Turnus, yet he attacks the Rutulian prince anyway. Pallas and Evander can be read as a corresponding pair to Aeneas and Ascanius. Like Evander, Aeneas is willing to give Ascanius his own control and his own persona, 22 and, like Pallas, Ascanius is often willful and daring. Merriam is right to point out that “heedlessness Here, Evander’s actions are unlike those of Anchises. For more discussion on Anchises’ role as father, see p. .9-13 20 Aeneid X 638-643. 21 Ibid, 635-636. 22 In Book IX, when he leaves Ascanius in charge of the Trojan troops. 19 Coleman 8 and immaturity…mark Ascanius throughout the epic,”23 and here, Pallas exhibits similar qualities. Thus, Pallas and Evander are exemplars of Aeneas and Ascanius. More importantly, they represent what will happen if Ascanius cannot learn the responsibility Aeneas is trying to teach him. Until this point, Ascanius has not “matured into a replica of his father,”24 and if he does not gain the traits of Aeneas (as Pallas could not gain the traits of pious Evander), he too will be vanquished by a more powerful enemy. However, the important difference between the relationship between Evander and Pallas and the relationship between Aeneas and Ascanius is the emotional outbursts in which Evander demonstrates his feelings. Unlike Aeneas and Ascanius, who always seem to respect and admire each other, the relationship between Evander and Pallas goes beyond pietas and is a real display of love, which seems to be lacking in the Trojans. Pallas and Aeneas Pallas’ surrogate father figure during his time at battle is Aeneas. Evander entrusts Aeneas with the care of his son at war, and sends Pallas off to fight beside the Trojan prince. After Pallas’ death, Aeneas is struck by a fit of furor: he goes on a killing rampage, attacking every Latin and Rutulian in sight. The most notable of these encounters is the death of Magus. As Aeneas is about to stab Magus, “ Magus is adroit enough to stoop, and quivering, the lance flies over him. he grips Aeneas’ knees and, suppliant, he begs him: ‘By your father’s Shade and by 23 24 Merriam, 860. For further discussion on Ascanius’ personality see p. 14-18. Ibid, 853. Coleman 9 your hopes in rising Iulus, I entreat, do spare this life for my own son and father.”25 It is notable here that Magus appeals to Aeneas in terms of both Anchises and Ascanius. He is appealing to Aeneas’ role as father and as son. However, Aeneas rejects Magus’ pleas, saying “this is what Anchises’ Shade decides, and so says Iulus.”26 After Aeneas’ grief-induced killing spree has ended with the death of Lausus and Mezentius, he begins to prepare to send the body to Evander, and for funeral games. During his preparations, Aeneas’ thoughts immediately travel to the Arcadian king and his reaction to his son’s death, wondering if Evander is preparing for his son to come back triumphantly, rather than lifelessly: “And even now, beguiled by empty hopes, perhaps Evander makes his vows and heaps his gifts upon the altar stone; while we, grieving, accompany the lifeless youth who now owes nothing to the gods, although we pay him useless honors.”27 The death of Pallas illustrates a very important characteristic of Aeneas, hitherto unseen: Aeneas is able to understand and feel parental love and grief. Until this point, Aeneas has shown literal interest in his own son, outside of concern for his destiny. Vergil has given no reason for the reader to believe that Aeneas is even capable of understanding the kind of paternal pietas and love that Evander feels for Pallas. However, by both his response to Pallas’ death, as well as his immediate thoughts of Evander, Vergil allows Aeneas to understand and himself feel the kind of love he has yet to show for Ascanius. 25 Aeneid X 718-724. Ibid, 732-734. 27 Ibid, XI 64-69. 26 Coleman 10 But perhaps more importantly, Aeneas’ reaction to Pallas’ death proves that he feels anxiety about his own role as father. Aeneas’ grief and furor after learning of Pallas’ death are understandable because “Pallas was his ward and he has failed to save him from death.” 28 If Aeneas can not save another man’s son, will he be able to protect his own? Aeneas’ rampage after Pallas’ death, ,then, allows the reader to understand some of the vulnerabilities of the Trojan prince: he is unsure of his own role as father (perhaps because his own father such a strong figure). Also, by justifying his murder of Magus in terms of Ascanius and Anchises, Vergil makes Aeneas’ actions the result of his pietas. Throughout his life, Anchises tried to teach Aeneas the value of pietas, and Aeneas continues to teach Ascanius. Like Aeneas’ comments to Lausus, then, this comments both the reader and Aeneas’ perception of what pietas truly is. Anchises and Aeneas We must understand Aeneas the son before we can hope to understand pater Aeneas. Anchises’ relationship with his son is a very loving one. This is best evidenced by the way Anchises greets Aeneas his ghost appears to Aeneas to tell him to go to the Underworld. He greets him in a loving, paternal way: “Son, once more dear to me than life when life was mine.”29 And the feelings are mutual. When Aeneas encounters his father’s ghost in Book V, 28 Gaskin, 300. Aeneid V 954-955. Also, note the similarities between Anchises’ address to Aeneas and Anna’s first address to Dido (Aeneid IV 38-39). 29 Coleman 11 he tries to embrace the old man and when he address him in the Underworld, “his face was wet with weeping as he spoke.” 30 Throughout the epic, Anchises is trying to teach Aeneas pietas, most specifically, the traits of clementia and philanthropia.31 However, although Anchises is a loving, caring parent, he is also over-bearing. More often than not, Anchises takes the reins from his son, forcing Aeneas to follow him (even if the elder statesman does not always know best). Anchises first leads Aeneas’ actions in Book III, when the father almost always dictates where the Trojans will travel. The most important actions undertaken by Anchises in this Book are the interpretation of the prophecy that tells Aeneas to return to his mother country and the Trojan’s acceptance of Ulysses’ former comrade Achaemenides. After receiving a prophecy from Apollo’s oracle that tells them to return to their mother land, the Trojans look to pater Anchises for guidance and interpretation. Despite the fact that the oracle called them “iron sons of Dardanus,”32 Anchises prefers to hearken back to the Trojans’ other ancestor, Teucer and send Aeneas and his men to Crete. Here, Anchises’ hermeneutic intervention was not only requested by Aeneas, it was followed blindly, without anyone (particularly Aeneas) questioning the validity or accuracy of the statement. Then, once the Trojans reach the island of Polyphemus, and encounter Achaemenides, former sailor under Ulysses, it is Anchises, not Aeneas who first offers him a hand of friendship. As soon as they see the ravaged Greek on the island of the cruel Cyclops, “Father Anchises does not wait long to offer his hand and steadies the young man with that strong 30 Ibid, VI 923 Khan, 232 32 Aeneid III 125. 31 Coleman 12 pledge.”33 It is not Aeneas, the nominal leader of the Trojans who decides to trust a Greek (even after they have been abused and deceived by Sinon and Ulysses himself). Instead, Aeneas allows his father to handle that position, while the prince waits placidly for his father’s word. Though Anchises does not appear in Book IV (except in Aeneas’ recounting of his adventures to Dido), he once again guides Aeneas’ actions in Book V, when it seems that Aeneas’ destiny may be off-track. Once Aeneas leaves Dido, he and his men are once again unsure of their next course of action. Fortunately enough they stumble across the p lace where Anchises is buried. After the funeral games Aeneas piously holds for his father, Anchises’ spirit comes to tell Aeneas to travel to the Underworld. 34 In Book VI, Anchises most famously foretells the future of Rome, the race Aeneas is fighting so hard to create. Aeneas, meanwhile is most grateful for Anchises’ presence, “Father, it was your sad image, so often come, that urged me to these thresholds.”35 Finally in Book VII Anchises again helps Aeneas posthumously, although this time indirectly. When Aeneas entreats King Evander for help in fighting Turnus and the Latins, Evander agrees, after remarking on Aeneas’ physical similarities to Anchises and Evander’s admiration for Aeneas’ father: “How I recall the words, the voice, the face of great Anchises!... As he walked, Anchises was the tallest of them all, And with young love, I longed to speak to him, To clasp his hand in mine…therefore, my right hand, 33 Ibid, 790-792. Ibid, V 952-974. 35 Ibid, VI 919-920. 34 Coleman 13 For which you ask, is joined in league with you.”36 It is because of Anchises’ strength and pietas as a leader that Evander remembers him and gives Aeneas troops and aid in his fight for Lavinia. So, even after death, Anchises guides and aids Aeneas in his quest to found the Roman race. While his relationship with Anchises remains important throughout Aeneas’ life, and while the guidance and leadership Anchises provides are crucial to the success of the Trojans and Aeneas, Anchises must die in order for Aeneas to become a true leader. It is only after the death of Anchises that Vergil begins to use the epithet pater Aeneas,37 and it is only after the death of Anchises that Aeneas truly becomes the commander of the Trojans. Aeneas finally becomes Anchises-like in Book VII, when arrives in Italy at last. Once he finally establishes a home for his men outside of Troy and his Trojan father, Aeneas himself begins to direct the action. However, the link to Anchises is not forgotten. When they arrive in Italy, Vergil writes that “Anchises’ son gives orders that a hundred emissaries, men chosen from each rank, be sent—to go before the king’s majestic walls.”38 Anchises has molded Aeneas in his image, and the younger Trojan is ready to take on the challenges of leading their people. Once he ascends from the Underworld, Aeneas “has acquired his father’s broader conception of pietas in which attachments to the individual members of his family are included within a devotion to the future.”39 36 Ibid, VIII 201-221. While it is true that Aeneas is called pater once in Book I, it is technically after the death of Anchises, which is told through flashbacks to Dido in Books II and III. 38 Aeneid VII 198-200. 39 Belfiore, 25. 37 Coleman 14 Anchises then, while slightly overbearing, is a prototype for Aeneas. By example, he teaches Aeneas how to rule the Trojans, and allows his son to develop the same sense of pietas that served him throughout his life and was so memorable to Evander. Ascanius Finally, then, discussion can be made about Ascanius and Aeneas’ relationship with him. The relationship between Aeneas and his son is complicated, at best. Although Ascanius and Aeneas appear together in virtually every book of Vergil’s epic, they very rarely communicate with one another, and no real parental or filial love is felt. In Book II, Aeneas is willing to sacrifice Ascanius’ life by remaining in Troy, even as the city burns around them. Because his father will not leave, Aeneas agrees to remain in Troy, even attempting to resume fighting until the end. 40 Aeneas shows little care for his small son, instead willing to follow his father blindly.41 In Book IV, it is not Aeneas who is negligent, but Ascanius who is capricious. When Ascanius joins Aeneas and Dido on their hunt in the Carthaginian woods, Ascanius is at first content simply to be invited—he is described as “glad Ascanius.”42 However, soon he becomes bored with the hunt: “But the boy Ascanius rides happily in the valleys on his fiery stallion as he passes on his course now stags, now goats; among the lazy herds 40 Aeneid II 908-910. Aeneas shows little care for his wife Creusa either, however, examination of Aeneas’ treatment of women is another topic for another paper. 42 Aeneid IV 187. 41 Coleman 15 his prayer is for a foaming boar or that a golden lion come down from the mountain.”43 Although Ascanius’ boredom is in no way the cause of the storm Juno and Venus send to force Aeneas and Dido to seek shelter in a cave, “when Ascanius is excited, we can be certain that excitement for all will follow.”44 Ascanius does not consider the effect a “foaming boar” or “golden lion” will have on the hunting party, and instead is focused entirely on his own entertainment. Book V finds Aeneas parading Ascanius in front of the Trojans during the funeral games for Anchises. Ascanius participates, with the Trojan youths, in a display of equestrian showmanship.45 In Book VII, Ascanius takes a more active role, first usurping Aeneas’ role of interpreter of prophecy, and later killing the deer that will, at least nominally, begin the war between the peoples of Italy and the Trojans. First, as Aeneas and his men are eating their first meal on Italian soil, Ascanius realizes that they have first placed bread on the ground, then the rest of the food on the bread. He remembers this as echoing the prophecy of Caeleno given to the Trojans in Book III, and, as Aeneas has done previously (and Anchises before him) interprets the data in front of him: “‘We have consumed our tables, after all,’ Iulus laughed and said no more. His words, Began to bring an end to Trojan trials; As they first fell from Iulus’ lips, Aeneas Caught them and stopped his son’s continuing; He was astounded by the will of heaven. He quickly cries: ‘Welcome, my promised land!’”46 43 Ibid, 207-212. Merriam, 854. 45 Aeneid V 750-754. 46 Ibid VII 147-153. 44 Coleman 16 It is important to note that Aeneas is quick to take up his son’s sentiment and turn it into his own victory. Here Ascanius has become a better prophet than Aeneas, because he has correctly interpreted the evidence in front of him, while Aeneas is often misinterpreting signs (as he does when he first see the mural on the walls of Dido’s temple in Carthage). Ascanius has begun to usurp Aeneas’ position as leader, and Aeneas is quick to put his son back in his place. Second, Ascanius kills the deer that will start the war between the Trojans and the Italians. This again is an example of the recklessness of Ascanius. The death of the deer does not come because Ascanius is hunting or trying to enact a ritual. Instead, “Ascanius himself, inflamed with the love of praise, had aimed an arrow from his curving bow; some god did not allow his faltering hand to fail.”47 It is his love of praise (perhaps from his father?) that leads Ascanius to kill the deer. In Book IX, Ascanius’ relationship with his father begins to resemble that of Aeneas’ relationship with Anchises. Ascanius becomes increasingly dependent on his father, and his father’s presence in his life. When Aeneas temporarily leaves the Trojan camp, and he becomes separated from Ascanius, Ascanius panics and sends Nisus and Euryalus to find his father, saying “recall my father, let me see Aeneas again; with his return, all grief is gone.”48 Though Ascanius has until now been portrayed as independent, willful and sometimes selfish, he suddenly adopts the passive role that Aeneas inhabited with Anchises. Aeneas, however, does not fill the lovingly paternal shoes that Anchises has left. When, in Book X, Aeneas is told that Ascanius is trapped by trenches and walls, hemmed in 47 48 Ibid 654-656. Ibid, IX 350-351. Coleman 17 by spears and war-mad Latins,”49 Aeneas does not seem concerned with his son’s safety. Instead, Vergil makes clear that “this omen lifts his heart,”50 and he rushes into the fray, never concerning himself with Ascanius’ well-being. He entirely ignores the welfare of Ascanius, instead focusing on the maintenance of Ascanius’ destiny and the victory of the Trojans. Finally, Aeneas leaves Ascanius with words of advice on how to govern, as Anchises did for him in Book VI: “From me, my son, learn valor and true labor; from others learn of fortune. Now my arm will win security for you in battle and lead you toward a great reward: only remember, when your years are ripe, your people’s example; let your father and your uncle— both Hector and Aeneas—urge you on.”51 Here, Aeneas is finally imparting his wisdom to Ascanius. He is instructing him on how to behave when he becomes the leader of the Trojans and how he can best embody the pietas of his ancestors. In his relations with his son, Aeneas is certain an embodiment of paternal pietas, yet there is no sense of true emotion between the two. His speech to Ascanius in Book XII is one of the few times that Aeneas actually addresses his son, even though they spend the entire course of the epic together. Ascanius, however, is not infallible either. Unlike his father, Ascanius does not seem to respond to the pietas his father is trying to impart. Instead, he continues to act willfully and selfishly and very rarely considers the well-being of anyone other than himself. At this point, 49 Ibid, X 333-334. Ibid, 351. 51 Ibid, XII 586-592. 50 Coleman 18 Ascanius is certainly not capable of ruling the Trojans, even though Vergil pointedly (and repeatedly) calls Ascanius “the second hope of mighty Rome.”52 Conclusions What, then, do these imperfect father-son combinations impart about Ascanius, Aeneas and the future of the Roman race? These father-son combinations, as well as the mistakes Aeneas himself has made as a son create a portrait of the ideal Vergillan father son combination, and of the correct way for Aeneas to mold young Ascanius. Aeneas is already on the right track with Ascanius by the end of Book XII. When Aeneas advises Ascanius on how to rule and what to remember as he grows up, he does not tell Ascanius to accept pietas like “Aeneas and Anchises.” Instead, he ignores the significant role his father has played in shaping his own concept of pietas, and focused on the contribution he himself has made to Ascanius. However, Aeneas is still too detached from his son’s personal well-being to be an effective father. Even at the end of Book XII, “pietas…imposes on Aeneas an isolation from his own family.”53 Aeneas’ concerns continue to be driven by the Trojan cause, not by concern for Ascanius himself. Ascanius’ role in the Aeneid should be of utmost importance to Aeneas. Throughout the epic, “Ascanius’ presence promises that there will be a future, but the happiness and security that the Trojan refugees dream of can be compromised by human folly, childish enthusiasm and heedless selfishness.” 52 Ibid, 226. Belfiore, 20. 54 Merriam, 860. 53 54 Aeneas and Ascanius must improve their Coleman 19 relationship, if only for the sake of the Trojans and the future of Rome. But how can they do this? By learning a lesson from each of the fathers and sons represented in the epic, the reader (and subsequently Aeneas can create the perfect Vergilian father and son combinations. First, from Mezentius and Lausus, we learn that it is dangerous to ignore responsibility to society and instead focus only on personal desire. Because Mezentius ignores his responsibilities towards Lausus (and the rest of his people) he misses out on the relationship he could have (and should have) been having with his son. While Aeneas is in no way guilty of ignoring his social responsibilities, Ascanius may be. Vergil is merely warning that this path (which Ascanius may or may not be headed down) only leads to destruction and tragedy. Pallas and Evander show what will happen if the differences between Aeneas and Ascanius’ relationship and an ideal father-son relationship are not sorted out. Evander is by all accounts the perfect father to Pallas. He is loving, but no overbearing, responsive and supportive. The only thing missing here from Aeneas’ relationship with his own son is the loving aspect. Aeneas must, like Evander, begin to not only respect and care for Ascanius, but express his paternal love for Ascanius as well. Ascanius, meanwhile needs to become more responsible. Like Pallas, Ascanius often leans towards irresponsibility and childishness. Through Pallas’ untimely death, Vergil is showing that if Ascanius does not reform, his story too will end in despair. Finally, Aeneas must learn from his relationship with his own father. Again, Anchises’ treatment of Aeneas proves that it is important to not only feel a sense of responsibility towards one’s son, but to express love as well, something Aeneas has not really Coleman 20 done until now. Also, Ascanius must realize that he cannot blindly follow where his father leads. When Aeneas blindly follows Anchises, the Trojans are often led off course, and delays ensue.55 Ascanius, therefore, must not continue to give into his weaker side as he does in Book IX and just follow Aeneas blindly. Instead, he must forge his own identity, at the same time he is obeying and respecting his father. The ideal Vergilian father, then is one who respects and admires his son, but also expresses his love for his progeny. He must have Anchises’ paternal pietas but like Evander must understand that his son must grow up and become his own man. The ideal Vergilian son must respect and love his father in return and understand the wisdom the pater can impart. However, he must never rely too heavily on his father’s guidance, as Aeneas often does, and focus on his own contribution to their society as well. Vergil uses father-son combinations, particularly in the later half of the Epic, to illustrate the wrong way to parent (and to respond to parental pietas). However, by synthesizing the portraits of fathers and sons, Vergil allows Aeneas, and subsequently the reader, to gain a clear picture of what the ideal manifestation of both paternal and filial pietas should be. 55 This occurs especially in Book III. Coleman 21 Bibliography Akbar Khan, H, “Anchises, Achaemenides and Polyphemus: Character, Culture and Politics in Aeneid 3, 588f,” Studies in Latin Literature and Roman History, ed. Carl Deroux, vol. 244 (Bruxelles: Latomus, 1998). Adkin Neil, “A Virgilian Crux: Aeneid 8.342-43,” American Journal of Philology 122.4 Belfiore Elizabeth, “Ter Frustra comprensa: Embraces in the Aeneid,” Phoenix 38.1 (1998): 19-30. Dewar Michael, “Mezentius’ Remorse,” The Classical Quarterly, 38.1 (1998): 261-262. Gaskin R, “Turnus, Mezentius and the Complexity of Vergil’s Aeneid,” Studies in Latin Literature and Roman History, ed. Carl Deroux, vol. 217 (Bruxelles: Latomus, 1992). Gotoff H.C, “The Transformation of Mezentius,” Transactions of the American Philological Association, 144 (2984): 191-218. James Sharon L, “Establishing Rome with the Sword: Condere in the Aeneid,” The American Journal of Philology 116.4 (1995): 623-637. Lloyd Robert B, “The Character of Anchises in the Aeneid,” Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philolgical Association, 88 (1957): 44-55. Merriam C.U, “Storm Warning: Ascanius’ Appearances in the Aeneid,” Latomus (2002): 852 860. Molyviati-Toptsis Urania, “Sed Falsa as Caelum Mittunt Insomnia Manes (Aeneid 6.896),” The American Journal of Philology, 116.4 (1995): 639-652. Petrini Mark, The Child and the Hero: Coming of Age in Catullus and Vergil (Ann Arbor: Coleman 22 University of Michigan Press, 1997. Schleiner Winfried, “Aeneas’ Flight from Troy,” Comparative Literature, 27.2 (1975): 97 112. Spence Sarah, “The Polyvalence of Pallas in the Aeneid,” Arethusa 32.2 (1999): 149-163. (2001): 527-531. Tracy H.L, “‘Fata Deum’ and the Action of the Aeneid,” Greece and Rome 2nd ser. 11.2 (1964): 188-195. Vergil, Aeneid, trans. Allen Mandelbaum, (New York: Bantam, 1971).