2ndyrbk.doc - University College Dublin

advertisement

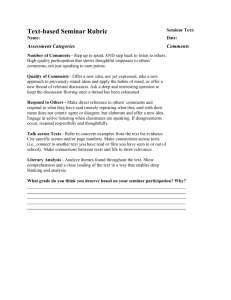

Department of English University College Dublin Second Year Course Booklet 2002 / 2003 Mode II 1 SECOND–YEAR ENGLISH 2002/3 Please read these notes carefully. If there is anything that is not clear to you do not hesitate to ask a lecturer, tutor, or Head of Year about it. It is YOUR responsibility to be fully acquainted with the challenges involved in moving from First Year into Second Year. If you are a visiting student or one transferring from another university it is your responsibility to make sure you know what the regulations are and what course requirements, tutorial arrangements, essay assignments and examination procedures are in place for the year. ERASMUS students must attend a special meeting which will explain requirements to them. Likewise, JYA students from the USA should consult the co-ordinator. Full details of courses and seminars on offer for Mode 2 students for the year 20022003 are included in this handbook. Please be sure you are completely familiar with these details. Mode 1 students should consult the Mode 1 booklet. Introduction The transition from First-Year English at UCD to Second Year requires a little bit of reflection. To a significant degree, First Year is a foundation year while Second and Third Years should be thought of as progressively developing certain skills laid down in First Year while introducing new material and new approaches to the study of English. The notion that Second Year is an interlude between the rigours of First Year and the trials of Third Year is no longer sustainable. Indeed, aggregation of marks between Second and Third Years is now on offer, on a 30% - 70% basis, which means that a good Second-Year Mark will help to raise the overall level of your B.A. degree and provide you with a basis of strength on which to enter the final undergraduate year. Such aggregation will apply only if beneficial to the student, who will receive either the combined 30% (Second Year) and 70% (Third Year) marks or the complete Third-Year mark, whichever is the higher. Please note: We expect all students to be fully committed, to do the work and to regard the Second Year as an important step towards the completion of their degree. In Second Year, Mode 2, you are required to attend three lecture-courses, one seminarcourse, and one tutorial, each week. Bear in mind that your attendance will be monitored and that you can be barred from sitting your examinations if your attendance is not satisfactory. So, if you have to take a job to help with finances during the year, ensure that this does not endanger your attendance requirements. You will be encountering seminar options in Second Year. You must attend and complete the work for two seminars over the year, one in each semester. Elsewhere in this booklet you will find a complete list of these Options, and you should make your choices during the first week of term. Choosing your options: Registration will take place on Monday 23 September in Room J208 from 10 until 12 and 2 until 3 on a ‘first come first served’ basis. The 'official' times, which will not clash with lecture times in other subjects, are: Mondays at 4, Tuesdays at 9 and Fridays at 4. Some other times will also be available, for example, Thursdays and Fridays at 1, Fridays at 10, 2 and 3. Check carefully that you have no clash of timetable if you choose any of these. 2 There is a generous number of seminars on offer and you should choose what you find challenging as well as interesting. You should not choose two seminars from the same general area, for example film studies or contemporary literature, but one from an early period (before 1800) and one from a later. You should also avoid choosing all poetry or all drama or all fiction, but try to set yourself a balanced diet. (In Third Year you will have the opportunity to achieve further variety in seminars.) You must bring a passport-sized photograph with you to registration, as well as your student card. Write your name and student number on the back of your photograph. Seminars begin on Monday 30 September, and run for nine weeks. The next seminars begin after Christmas, on 6 January 2003. Protocol Do understand that when you sign on for a seminar you enter a contract: you agree to do the reading each week, to participate in class discussions, and to do all you can to further the success of the seminar. This contract subsists even when you haven’t obtained the seminar of your choice. In essence, all of this comes down to attitude. If you are positive towards the seminar you will want it to succeed and will work towards that end. But you must not expect the seminar leader to give a lecture each time: that is not how it works. Neither is a seminar a tutorial. The difference is partly the greater numbers in a seminar (up to 15) and partly the greater responsibility on each member of the class to prepare something specific for each session. The main thing to remember is that there are new skills to be learned and one of these is better communication, which in this instance means better focus on issues and problems. It is for you to ‘problematise’ a text under discussion, to find beforehand areas of the text which should give rise to questioning and to raise such questions in an exploratory way. It is time now to move beyond the “I like ... I hate” response to a text, as if the teacher were responsible for defending if not for actually authoring the text. The approach now is a common one, an entry to the text so that gradually there can be something like a consensus about its value, meaning and/or significance as a piece of writing. This approach requires patience, a living with awkward and perhaps even unpalatable elements in the text, and a coming to the kinds of answers which do justice to the text according to clearly understood aesthetic principles. But there may be no answers as such; there may be only a constant friction with the text. It does not matter. So long as there is honest engagement with the text there will be progress, even if that progress does not appear there and then. It will come later, with more thought expended on the problem, and with more reading. A seminar is therefore work in progress and its success depends on the willingness of those in it to take responsibility. Attendance is obligatory. A penalty of 10 marks will be levied if a student misses more than three classes without a medical certificate or other valid documentation supplied to the teacher (or, if required, to the Head of Year). In Second-Year English you will have one tutorial a week. Six out of the nine tutorials provided for each semester will be in Modern, three in Old and Middle English. You will not change rooms for this tutorial but change tutors. The tutorial will focus on the core courses, 3 for the purposes of practical criticism/critical analysis and short essays in comparative criticism. There will be a special examination paper devoted to testing these skills together with your ability to think laterally about texts (both Modern and within the ambit of Old and Middle English), that is, to consider how issues and techniques have been employed by diverse writers across wide stretches of literary history. Tutorials: In addition to what has been said above, it may be emphasised that the tutorial in Second Year fulfils very special functions. The tutorials provide opportunities for the student to bring to the tutor any questions or problems being experienced in the core courses, but there is no purpose of ‘coverage’ of material in all the core courses. The tutorials will assume that you are working on your own and will serve to focus discussion on matters arising from the course work rather than seek to provide handy synopses or the like. You are expected to work on your own But perhaps the main function of the tutorial in Second Year, and this is why attendance is vital, is to assist in the leap from First Year to more concentrated, investigative, and analytical methods of studying English. In that sense, then, a tutorial is a kind of workshop. You may be asked to write short trial pieces, short essays in practical criticism. These will help you to develop certain valuable skills and you would be wise to regard them as necessary exercises. It would be foolish not to avail of the tutorial as a special study aid. The kind of work you are expected to produce in Second Year tends to be defined by what goes on in tutorials. You should use them actively and with a positive outlook. Tutorial Registration: Wednesday 25th September, Room J207, 10 am – 1 pm. Tutorials begin the week of 30 September, and resume in second semester on 20 January. Essays: Two essays are due, one for each seminar. (Mode 1 students will have five essays: see separate booklet for details.) Each essay (one in each semester) should be 3,000 words in length and should follow the style sheet provided by the department (see back of booklet). Note that a total of 250 marks is available for these essays in the continuous assessment process. This figure represents one-third of the marks given for examinations (750), so the essays are vital. The due dates for submission of these essays are: Essay 1 (first semester): Monday 16 December 2002 Essay 2 (second semester): Monday 10 March 2003 Note: These dates are out of term. Submission by registered post is acceptable if postmark shows correct date. Regulations: You must ensure that you get your essays in on time, i.e by 4.30 p.m. to room J201 on the due date, or marks will be deducted as follows: 10 marks during the first week an essay is late (Monday to Friday), 20 marks during the second week an essay is late, 30 marks (maximum) before the end of the year (17 April 2003), 50 marks after 17 April. Essays cannot be accepted once examinations begin on 28 April 2003. 4 In general, only a relevant medical certificate or verifiable personal excuse will be an acceptable basis for an extended deadline. You must complete a ‘Cover Sheet’ for each essay, and ensure that this is date stamped upon submission. Plagiarism, the appropriation of material without quotation marks or without proper acknowledgement of the source, is likely to result in a mark of zero. Remember, plagiarism is a serious offence. Essays should be typed, where possible (and where not possible must be legibly written on one side only of each page). Essays should always cite references and supply a bibliography or list of ‘works cited’. The style sheet should be obeyed. Hints for essay writing Together with the critical analysis required for tutorials, the kind of essay required in Second Year is a well-planned, well-organised exploration of some selected topic, as agreed with your seminar leader. The bases of the essay should be analysis and argument, not paraphrase or plot summary, with examples carefully chosen to back up your argument. Sweeping generalisations should be avoided. Instead, you should attempt to develop a logical argument by using specific evidence or examples drawn from a textual base. Further, it is not a good idea to load an essay with lengthy quotations from ‘experts’, as if their views represented the last word on the issue. This is a lazy way to write. You must grapple with the problems raised by the essay topic and where you use ‘experts’ you should enter into dialogue with them and seek to assimilate their views in an argumentative spirit. Second Year offers the opportunity to develop new and necessary skills in a more speculative type of essay. You will receive all the help and advice you need to do this, in tutorials and in seminars, but the other side of the coin reads: sloppy work will be severely punished. Problems: In the nature of things, there will be problems. The one thing you must not do is run away from them. There is help all around you, for the English Department has a reputation for being friendly and concerned. Look to your tutor as the first person on whom to call if you are in difficulty of any kind. If there is a problem with your seminar, talk to the leader after class or make an appointment to see her or him. You might find yourself in a situation where you feel stressed. Well, that too is part of university life, but it doesn’t mean you have to suffer through the whole year. Talk to someone. The Head of Year is there for that purpose. In Modern English her name is Dr Anne Fogarty and her room number is J211. Her telephone number is 716 8159. You may also contact those working with Dr. Fogarty this year: Mr Brian Donnelly, Room J214, Tel. 716 8160 and Dr. Eldrid Herrington, Room C209, Tel. 716 8622. In Old and Middle English the Head of Year is Professor T. P. Dolan, whose room number is J215. His telephone number is 716 8156. Final Comments: Acquaint yourself also with the staff-student committee (or better still, volunteer to be a class rep.) and watch out for the news and notices emerging from that body, which meets a couple of times each semester. If you have a specific problem with the year’s work or courses why not bring it to the class rep? Always keep your eye on the Second-Year notice board for communications of various kinds throughout the year. You should note that information about examinations, layout of papers, etc, will be posted here. Remember, it is your responsibility to make yourself aware of such information. If in doubt about any notice you read on the notice board ask for 5 clarification at the Departmental Office (J206, telephone 716 8323 or 716 8157 or 716 8480). Website address www.ucd.ie. The Head of the Combined Departments of English for the academic session 2002/2003 is Professor Mary Clayton, Professor of Old and Middle English. The Head of the Old and Middle English Department is Professor Mary Clayton, Room J205, Tel. 716 8251. Administrator: Pauline Slattery, Phone 716 8157, Room J206 (a.m. only) The Head of the Department of Modern English and American Literature is Professor James Mays, Room J202, Tel. 716 8346. Administrator: Lena Doherty, Phone 716 8323, Room J206. Administrator: Marguerite Duggan, Phone 716 8157, Room J206 (p.m. only) The Head of the Department of Anglo-Irish Literature and Drama is Professor Declan Kiberd (on leave from January 2003), Room J203, Tel. 716 8348. Administrator: Helen Gallagher, Phone 716 8480, Room J206. The staff and faculty in Second-Year English welcome you most warmly and hope you have a happy, fruitful year working with us. 6 Lecture Schedule Second Year 2002-2003 Term begins 16 September 2002 FIRST SEMESTER Early Modern Literature: Licence, Play and Power (ENG 2003) Lecturers: Dr. Janet Clare and Dr. Jerome de Groot Mondays 12 noon Theatre L This course will develop students’ understanding of the culture of the Renaissance. As the first year course demonstrated, early modern literature drew inspiration from the revival of classical learning and from the literary forms of continental Europe. But this was also a period in which represented authority was challenged and resisted. Popular initiatives in drama and prose subverted social norms and questioned established ideologies. Women writers, employing different material practices and aesthetic strategies, brought new perspectives to dominant ideas of gender. This course aims to examine the relationships between authority and subversion by looking at selected early modern texts, concepts and locations (the theatre, ideal spaces, the street). Students will be introduced to key ideas relating to the links between high and low culture, the oral and the written, the medieval and the modern, ritual and Reformation, alongside an introduction to some key concepts: carnival, parody, humanism, rhetoric, and ideas about the body. Students will be expected to be able to make connections between the texts on the course and relate them to the secondary reading. REQUIRED TEXTS: Sir Thomas More, Utopia (Penguin) William Shakespeare, Measure for Measure (Arden or any good edition) William Shakespeare, A Midsummer Night's Dream (Cambridge) Ben Jonson, Bartholomew Fair, ed. Suzanne Gossett (Manchester UP) Thomas Nashe, The Unfortunate Traveller and other Works, ed. J.B.Steane (Penguin) Ballads and satires (course materials provided). MODERN ENGLISH: THE NINETEENTH CENTURY (ENG 2004) Lecturers: Dr Eldrid Herrington and Professor James Mays Wednesdays 2 pm Theatre L Your aim should be: to know something about Romantic writers, at least those in the anthology and a few others—how their writing works, what there was to be excited about, how understanding is mediated by ideology. This last matter involves, among other things: the formation of and debate over a Romantic Period canon; questions of influence and 7 intertextuality within generations of writers; gender issues; and the relation of art to history and politics. All poems are to be found in volume II of the Norton Anthology of English Literature (2000; 7th edition). 1 ROMANTICISM AS SITE AND IDEOLOGY (Prof Mays) Victorian Construction and Postmodern Deconstruction (Arnold and Eliot, Wellek and Hartman, Abrams and McGann) 2 ‘THE PICTURE OF THE MIND’: WORDSWORTH AND MEMORY (Dr Herrington) William Wordsworth, ‘Composed Upon Westminster Bridge, 1802’ and ‘Tintern Abbey’ 3 WORDSWORTH AND THE NEW SCHOOL (Prof Mays) quatrain poems from Lyrical Ballads and Lucy poems; also ‘Resolution and Independence’, ‘Michael’, ‘Tintern Abbey’, ‘Intimations Ode’ 4 THE RIME OF THE ANCIENT MARINER (Dr Herrington) Samuel Taylor Coleridge, The Rime of the Ancient Mariner 5 THE GREATER ROMANTIC LYRIC (Prof Mays) Coleridge’s ‘Aeolian Harp’, ‘Lime-Tree Bower’, ‘Frost at Midnight’; Wordsworth’s ‘Tintern Abbey’, ‘Intimation Ode’, ‘Michael’; Keats’s ‘Nightingale’, ‘Grecian Urn’, ‘Autumn’; Shelley’s ‘West Wind’, ‘Skylark’ 6 CANT V C*NT (Dr Herrington) George Gordon, Lord Byron, Don Juan, Cantos I and II only 7 SENSIBILITY AND GENDER (Prof Mays) The debate about women’s education using selections from Wollstonecraft’s Rights of Women, Dorothy Wordsworth’s Journals; references to Charlotte Smith, Felicia Hemens, Jane Austen and Mary Shelley 8 ‘SOCIAL LONELINESS’ (Dr Herrington) John Clare, ‘I am’, ‘Pastoral Poesy’, ‘Mouse’s Nest’, ‘The Nightingale’s Nest’, ‘The Peasant Poet’ 9 ROMANTICISING JOHN KEATS (Prof Mays) ‘Grecian Urn’, ‘Nightingale’, ‘Autumn’ 10 KEATS’S READING (Dr Herrington) John Keats, ‘On First Looking Into Chapman’s Homer’, ‘On Sitting Down to Read King Lear Once Again’, ‘The Eve of St Agnes’, ‘La Belle Dame Sans Merci’ 11 CONCLUSION (Dr Herrington) Secondary Reading Abrams, M. H. The Mirror and the Lamp (1953) 8 ———. Romantic Supernaturalism (1971) ———. The Correspondent Breeze (1984) Bromwich, David. Disowned by Memory: Wordsworth's Poetry of the 1790s (1998) Butler, Marilyn. Romantics, Rebels and Reactionaries (1981) Chase, Cynthia, ed. Romanticism (1993) Curran, Stuart, ed. Cambridge Companion to British Romanticism (1993) Dabundo, Laura, ed. Encyclopedia of Romanticism: Culture in Britain, 1780s-1830s (1992) Favret, Mary, ed. At the Limits of Romanticism (1994) Hartman, Geoffrey. Wordsworth’s Poetry, 1787-1814 (1964; 1971) Kroeber, Karl, ed. Romantic Poetry: Recent Revisionary Criticism (1993) McGann, Jerome. The Romantic Ideology (1983) ———. The Poetics of Sensibility: A Revolution in Literary Style (1996) McGann, Jerome, ed. The New Oxford Book of Romantic Period Verse (1993) Mellor, Anne, ed. Romanticism and Feminism (1988) Perry, Seamus. Coleridge and the Uses of Division (1999) Prickett, Stephen. Wordsworth and Coleridge: 'The Lyrical Ballads' (1975) Wu, Duncan. A Companion to Romanticism (1998) THE CANTERBURY TALES (ENG 2001) Lecturers: Prof. P Lucas, Prof. T.P. Dolan, Prof. M. Clayton, Dr. M. Robson, Dr A. Fletcher Thursdays 9.00 am Theatre M The Canterbury Tales is probably the most famous work of Middle English literature, but it remains a complex, controversial and infinitely fascinating text - or collection or texts. Students will be invited to make detailed critical studies of individual Tales, to make comparisons and contrasts between them, and/or to consider the scope and effect of the Tales as a whole. There will be lectures on the Tales (and Prologues) of the Wife of Bath and the Pardoner - two of Chaucer's most grotesquely memorably characters - the Merchant and the Nun's Priest - who tell very different comic stories - and the Clerk and the Franklin - in which Chaucer explores (or pretends to explore) some apparently idealized relationships between men and women. REQUIRED TEXTS: The Canterbury Tales, (Riverside edition) OR The Norton Critical edition of The Canterbury Tales Nine Tales and the General Prologue, ed. V.A. Kolve and Glending Olson September 19 September 26 Introductory Lecture The Wife of Bath 9 Dr Robson Dr Robson October 3,10 October 17, 24 November 7 November 14,21 November 28 December 5 The Merchant's Tale The Franklin's Tale The Clerk's Tale The Pardoner's Tale The Nun's Priest's Tale Concluding Lecture Dr Robson Prof Lucas Prof Clayton Dr Fletcher Dr Robson Prof Dolan READING WEEK: OCTOBER 28 – NOVEMBER 1, 2002, INCLUSIVE. LECTURES, SEMINARS AND TUTORIALS WILL NOT BE HELD DURING THIS WEEK. TERM DATES: 16 SEPT – 6 DEC 2002 10 SECOND SEMESTER 6 January 2003 - 17 April 2003 Term Break 2 March - 23 March (Term dates: 6 January – 1 March 2003 24 March – 17 April 2003) AN INTRODUCTION TO OLD ENGLISH (ENG 2002) Lecturers: Professor Clayton, Professor Lucas, Dr. Robson Mondays 12 noon Theatre L The first part of this course offers an introduction to Old English language, aimed at giving a basic competence in reading Old English. We will then look at three texts: an extract from Apollonius of Tyre, a romantic tale of shipwreck and love, the Wife’s Lament, a lyric poem about the desolation of a woman in exile, and some Old English riddles. Jan. 6, 13, 20, 27, Feb. 3 Feb. 10, 17 Feb. 24, Mar.24 Mar. 31, Apr.7 Old English Grammar Apollonius of Tyre Old English Riddles Wife’s Lament Prof Clayton Prof Clayton Dr. Robson Prof. Lucas REQUIRED TEXTS: Texts will be provided on handouts and made available in the Students' Union for copying. ANGLO-IRISH LITERATURE: EXCAVATING THE PRESENT (ENG 2006) Lecturers: Dr Catriona Clutterbuck, Dr Anthony Roche Wednesdays 2.00 pm Theatre L This course examines how a series of key contemporary Irish texts interrogates the uses of the past in the construction of present-day national, regional, gendered, familial, personal and artistic identities. The theme of tension between these identities is central to the texts. The post-colonial condition, which forms a vital backdrop to understanding contemporary Irish writing, will itself be examined through the lens of alternative frameworks of interpretation, especially those enabled by feminist theory. The value of literature in contexts of cultural and political conflict will be an important focus of exploration in this lecture series. (N.B. End-of-year examinations will be based on the assumption that all five texts are read in full by students) 11 REQUIRED TEXTS: Boland, Eavan, Outside History, (Carcanet, 1990) Devlin, Anne, After Easter, (Faber, 1994) Heaney, Seamus, North (Faber, 1975) McCabe, Patrick, The Butcher Boy, (Pan Macmillan, 1992) McGahern, John, Amongst Women, (Faber, 1990) A number of key articles will also be made available to students. THE LITERATURE OF EXTREMITY: AMERICAN WRITING AFTER 1945 (ENG 2005) Names of Lecturers to follow. Thursdays 9.00 am Theatre M This lecture course seeks to introduce students to American writing after the Second World War. On the surface of things, the immediate post-war period represented a time of material plenty and social stability. However this ‘official’ emphasis on traditional values of family and domesticity, backed up by rapid economic growth and a new culture of consumption, often provoked an undercurrent of anxiety and entrapment in the nation’s writers. The works on this course often depict moments of crisis, instances of emotional failure, and a general disquiet with an America rapidly assuming superpower status. Writing after the extremes of the holocaust and Hiroshima, many of these writers describe a country ill at ease with itself, trying to make sense of its post-war, cold-war position in the world. PRIMARY READING LIST: (PROVISIONAL: THIS LIST MAY BE MODIFIED AFTER SEPTEMBER 2002. PLEASE CONSULT NOTICEBOARD). Flannery O’Connor, The Complete Stories of Flannery O’Connor (Faber and Faber, 2000) Walter Moseley, Devil in a Blue Dress (1990) (Serpent’s Tail, 1991) Thomas Pynchon, The Crying of Lot 49 (1966) (Vintage, 1996) Robert Lowell, Life Studies (1959) (Faber and Faber, 2001) J. D. Salinger, The Catcher in the Rye (1951) (Penguin, 1994) Saul Bellow, Seize the Day (1956) (Penguin, 2001) Philip Roth, American Pastoral (1997) (Vintage, 1998) Students will also need The Norton Anthology of Poetry. They should already have this from first year. SUMMER EXAMINATIONS: 28 APRIL (PROVISIONAL) AUTUMN EXAMINATIONS: 11 AUGUST (PROVISIONAL) 12 SEMINARS NOTE: It will not be possible to give every student her or his firstpreference options, because of the numbers taking Second-Year English. When registering, it more than likely will be necessary for you to keep choosing from the list of seminars until you get a vacancy. Seminars will be allocated on a ‘first come first served’ basis. 13 Second-Year Seminars (Mode 2) First Semester (ENG 2008) Choose one, as available SEMINAR LEADER SEMINAR TITLE Dr Barrett Dr Barrett Dr Brannigan Mr Byrne Stage Speech * Shakespeare's Stagecraft * Brendan Behan Dr Callan Prof Carpenter Dr Clare DAY AND TIME ROOM Monday, 4pm Friday, 4pm Thursday, 1pm Monday, 4pm J207 J207 J208 F106 Early American Writing Readings in 17th C. English Poetry * Hamlet and Revenge Tragedy * Monday, 4pm Monday, 4pm Thursday, 1pm D112 J112 D112 Prof Clayton Prof Clayton Dr de Groot Prof Dolan Dr Fogarty Dr Herrington Prof. Kiberd Dr Killeen Prof. Lucas Prof. Mays Dr Meaney Medieval Fabliaux* Medieval Fabliaux* Contemporary Women Writers Humour: Medieval to Modern Gothic Fiction Walt Whitman Joyce's Ulysses * Children's Literature* Old English for Beginners William Blake Monstrous Speculations Tuesday, 9 am Friday, 10 am Tuesday, 9am Thursday, 1pm Tuesday, 9am Monday, 4pm Monday, 4pm Tuesday, 9am Thursday,1pm Thursday,1pm Friday, 10am Ms O'Neill Ms O' Neill Dr Robson Dr Sheppard Ms Stierle A.N. Other Romance and Lai Romance and Lai The Arthurian Tradition Shakespeare, Comedy and Film Gender Roles in Contemporary Film To be announced Monday, 4pm Friday, 10am Friday, 10am Friday, 4pm Monday, 4pm Monday, 4 pm J114 J110 J112 J112 J207 J110 E106 J208 D108 J110 Arts Annexe F101A J112 J208 J208 J208 F106 Fight for the Right to be Black: The Struggle for African American Identity * Offered in the First Semester only. Note: First Semester seminars begin week of Monday 30 September. 14 Second-Year Seminars (Mode 2) Second Semester (ENG 2009) Choose one, as available SEMINAR LEADER SEMINAR TITLE Dr Brannigan Mr. Byrne Brendan Behan Dr Callan Prof. Carpenter Dr de Groot Prof. Dolan Mr Donnelly Dr Fletcher Dr Fogarty Dr Herrington Prof. Lucas Prof. Mays Dr Meaney Ms O' Neill Dr Robson Dr Roche Dr Roche Dr Sheppard Ms Stierle Dr. Stuart A.N. Other DAY AND TIME ROOM Thursday, 1pm Monday, 4 pm J208 F106 Early American Writing Gulliver's Travels * Contemporary Women Writers Humour: Medieval to Modern Poetry in English* Gothic & Gothick* Gothic Fiction Walt Whitman Old English for Beginners William Blake Monstrous Speculations Monday, 4pm Monday, 4pm Tuesday, 9am Thursday, 1pm Friday, 2pm Monday, 4pm Thursday, 1pm Monday, 4pm Thursday, 1pm Thursday, 1pm Friday, 10am Romance and Lai The Arthurian Tradition Joyce's Ulysses * Joyce's Ulysses * Shakespeare, Comedy and Film Gender Roles in Contemporary Film Emily Dickinson* To be announced. Monday, 4pm Friday, 10am Thursday, 1pm Friday, 2pm Friday, 10am Monday, 4pm Friday, 1pm Monday, 4 pm D112 J112 J112 J112 J104 J114 J207 J110 D108 J110 Arts Annexe F101A J208 J114 J114 J207 J208 F101A F106 Fight for the Right to be Black: The Struggle for African American Identity *Offered in the Second Semester only. Note: Second Semester seminars begin Monday 6 January. 15 Seminar Descriptions and Booklists Stage Speech (First Semester only) Dr John Barrett Monday 4pm This option explores the strengths and limitations of dramatic, as opposed to narrative, writing. It examines such conventions as Direct Address, Soliloquy, the Alter Ego device, Single Narrator, Multiple Narrators etc. Required Reading: Eugene O’Neill Strange Interlude. (Nick Hern) Sarah Daniels: Beside Herself (Methuen) Peter Nichols: Passion Play. (Methuen) Edward Albee: Three Tall Women (Penguin) Brian Friel: Plays : 1 (Faber) Brian Friel: Plays: 2 (Faber) Shakespeare's Stagecraft (First Semester only) Dr John Barrett Friday 4pm This option will explore, in the first place, the physical conditions of Shakespeare's Globe Theatre and examine the ways in which it determines his stagecraft. We will see how Shakespeare manages his scenes, in terms of length and location, and in the same context examine the technical demands of exits and entrances, opening and closing of scenes, the management of props etc. We will then focus on how these and other factors present challenges to contemporary directors of Shakespeare and discuss how these challenges can be met. Texts: King Lear Hamlet Othello Macbeth The Merchant of Venice The New Arden editions are preferable, with the exception of Hamlet,where the New Cambridge edition (ed.Philip Edwards) is recommended. 16 Brendan Behan Dr John Brannigan Thursday 1pm Brendan Behan is a controversial figure in Irish Literary history, more renowned for his stage- Irish antics and his patronage of Dublin's pub culture than for his writings. This course aims to examine, in the sobering light of day, the nature of Behan's literary legacy. It will assess Behan's formal experiments with dramatic structure, short fiction, the autobiographical novel, and the anecdotal sketch. The course will explore Behan's oeuvre for his representations of mid-twentieth-century Ireland, his engagement with cultural nationalism (particularly of the revival period), and his flirtation with dissident social, sexual and political identities. Course Texts: Brendan Behan The Complete Plays (Methuen) Borstal Boy (Arrow) After the Wake (O' Brien) The Dubbalin Man (Farmar) Recommended Reading: Boyle, Ted Brendan Behan (Twayne) Brannigan, John Brendan Behan: Cultural Nationalism and the Revisionist Writer (Four Courts) Brown, Terence Ireland: A Social and Cultural History, 1922-1985 (Fontana) Kearney, Colbert The Writings of Brendan Behan (St Martin's Press) Kiberd, Declan Inventing Ireland: The Literature of the Modern Nation (Jonathan Cape) Murray, Christopher Twentieth-Century Irish Drama (Manchester UP) O' Connor, Ulick Brendan Behan (Abacus) O' Sullivan, Michael Brendan Behan: A Life (Blackwater) Roche, Anthony Contemporary Irish Drama: From Beckett to McGuinness (Gill and Macmillan) Fight for the Right to be Black: The Struggle for African American Identity Mr James Byrne Monday 4 pm This course seeks to investigate on three separate levels – the physical, the aesthetical, and the polemical – the African American transition from slave to citizen. That this has not been an easy transition is an obvious understatement and so, in the quest to come to understand the depth of struggle, suffering and conviction it took to achieve this goal (some would argue that this goal has not yet been achieved), this course struggles to understand the courage of body, spirit and mind needed to take up this quest form three different yet similarly harsh roads towards the one goal – equality. 17 Required reading: David Remnick, King of the World Zora Neale Hurston, Their Eyes Were Watching God Arthur Hailey, The Autobiography of Malcolm X Early American Writing Dr Ron Callan Monday 4pm This course begins by examining some of the writing which reflected American experiences before "The Great Republic" came into being. Our texts will range from Puritan to Native American accounts of America, and from black writing to expressions of hope for a new nation. We will consider a range of views which together express the diversity of what was to become the United States of America. The course will include a good deal of material which is not considered literature. We will read autobiographies, journals, letters, sermons and transcriptions and translations of oral tales together with a range of early American poetry. Students will be encouraged to participate in class discussions, and to develop their interests within the terms of the course. Required Reading: Nina Baym et al, eds. The Norton Anthology of American Literature. 5th ed., Vol. I. London: Norton, 1998. Please note: The Norton was the text for "The American Renaissance" course in First Year English. *Additional reading will be assigned in class. Readings in seventeenth-century English poetry: The Metaphysicals and their contemporaries. Prof. Andrew Carpenter (First Semester only) Monday 4pm This course will cover in detail the poetry of Donne, Herbert, Marvell and other metaphysical poets of seventeenth-century England, as well as some of the work of their contemporaries, Jonson, the cavalier poets and the young Milton. Attention will also be paid to the intellectual, literary, social and political background to the poetry we shall be studying. Required reading: The Norton Anthology of Poetry (4th ed.). 18 Other recommended or required texts may be downloaded from Literature Online (LION) on the UCD website. Gulliver's Travels Prof. Andrew Carpenter (Second Semester only) Monday 4pm A close reading of one of the key text of the eighteenth century, Jonathan Swift's Gulliver's Travels. Students will be able to explore specific aspects of the text which interest them from early on in the course. Required reading: Any modern paperback text of Gulliver's Travels, provided it is unabridged and unexpurgated. Acceptable editions include Penguin Popular Classics and Everyman Hamlet and Renaissance Revenge Tragedy Dr Janet Clare (First Semester only) Thursday 1pm ‘A kind of wild justice’ was how Francis Bacon described revenge in his essay on that subject published in 1597. Revenge – regarded by the legislator as anti-social; by the moralist as barvaric and by the theologian as a sin – is recognised as a widespread instinct and deeply rooted in human nature. From Greek drama onwards revenge has powerfully figured as both a motive for action and a motif of tragedy. Dramatic perspectives on revenge have been guided by the cultural context. This course will examine the representation of revenbe in the theatre of Shakespeare and his contemporaries. The enactment of revenge made effective theatre in a period accustomed to gruesome spectacle. Are revenge tragedies then merely sensational? We will explore the moral and socio-political issues raised in the plays and questions relating to revenge and honour, the woman’s part, and revenge and subjectivity. Required Reading William Shakespeare, Titus Andronicus, edited Jonathan Bate (Arden Shakespeare) Hamlet, edited T.J.B. Spencer (Penguin Shakespeare) Four Revenge Tragedies, edited by Katherine Eisaman Maus (World Classics) John Webster, The Duchess of Malfi, edited John Russell Brown (Student Revels) 19 Medieval Fabliaux Professor Mary Clayton Friday 10 am Fabliaux are comic tales in verse, set in the contemporary everyday world, rather than the aristocratic world or romance, with plots that generally involve some sort of trickery, often motivated by sexual desire. Very popular in France and Italy, the genre was taken up in English primarily by Chaucer. This seminar will concentrate on the fabliaux which form part of the Canterbury Tales and will consider issues of gender and class. Note: All students should possess the Riverside Chaucer for this course. Contemporary Women Writers Dr de Groot Tuesday 9am This seminar will introduce students to the works of several important contemporary female authors. The seminars will consider issues of genre, style, narrative, gender and politics as well as exploring the novels using elements of postcolonial, postmodernist and feminist theory. Texts: Margaret Atwood, Alias Grace (Virago, 1997) Angela Carter, Wise Children (Vintage, 1992) A.L. Kennedy, Now That You’re Back (Vintage, 1995) Toni Morrison, Beloved (Vintage, 1997) Jeannette Winterson, The Passion (Vintage, 1996) 20 Humour: Medieval to Modern Professor Dolan Thursday 1pm This course discusses the theory of comedy, taking Geoffrey Chaucer’s humour as its starting point. It considers the element of subversion in humour, as well as its cruelty, and by studying a selection of writings from Chaucer to the present it seeks to identify the permanent elements in comedy, as distinct from those which change or disappear according to fashion and taste. Recommended: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Nash, Walter, The Language of Humour: Style and Technique in Comic Discourse, 1985. Chapman and Foot (eds.), Humor and Laughter. Theory, Research and Applications, 1996. Rodway, Allan, English Comedy: Its Role and Nature from Chaucer to the Present Day, 1975. Steadman, John M., Disembodied Laughter, 1972. Jost, J. (ed.), Chaucer’s Humor, Critical Essays, 1994. Poetry in English - 17th Century until the Present Mr Brian Donnelly (Second Semester only) Friday 2pm Readings in selected poems by Irish, British, American and Commonwealth writers. Emphasis will be placed upon the relationships between tradition, form and the individual talent. The development of the skills of close, careful, critical analysis of the texts will be a major aim of this seminar. Required Text: The Norton Anthology of Poetry, ed. Margaret Ferguson et al. with additional material from The Norton Anthology of English Literature, Volume I, ed. M.H. Abrams et al. 21 Gothic and Gothick Dr. Alan Fletcher Monday 4pm This course will examine how medieval culture was perceived in English literature between the late-eighteenth and the twentieth centuries, and the purposes for which that culture was exploited. Set prose texts are: Montague Rhodes James, Casting the Runes and Other Ghost Stories, Oxford World Classics, ISBN 019-283773-7. Short stories for special attention are ' Oh, Whistle, and I'll Come to you, My Lad', 'Casting the Runes'. And 'The Stalls of Barchester Cathedral'. Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu, In a Glass Darkly, Oxford World Classics, ISBN 019-283947-0. Short stories for special attention are: ' Carmilla' and 'Green Tea'. Matthew Lewis, The Monk This is available in Four Gothic Novels, Oxford World Classics, ISBN 019-282331-0. Edgar Allen Poe, Selected Tales, Oxford World Classics, ISBN 019-283224-7. Short stories for special attention are: 'Masque of the Red Death', 'The Fall of the House of Usher', ' Ligeia', and ' The Pit and the Pendulum'. Set verse texts, which will be circulated in class, are: John Keats, 'La Belle Dame sans Merci' and 'The Eve of St Agnes'. Edgar Allen Poe, 'The Bells', 'The Conqueror Worm', 'The Raven'. Alfred Lord Tennyson, 'The Mariana', 'Godiva', and 'The Lady of Shalott'. Criticism Since this course intends that you think for yourself and evolve your own opinions about the issues that will be raised, a long list of secondary critical writing may be a hindrance. However, one prompt to your further critical reflection that you may consider reading is Fred Botting, Gothic (London: Routledge, 1996). Also, since the course will be encouraging you to read the set texts inventively, you might find Martin Montgomery, et al., Ways of Reading, 2nd ed. (London: Routledge, 2000), a useful introduction to just a few of the many different ways in which a text can be approached. 22 Gothic Fiction Dr. Anne Fogarty Tuesday 9am (First Semester) Thursday 1 pm (Second Semester) The concept of the gothic has become increasingly contested. This course sets out to explore the variable histories of this genre and to consider the extent to which this mode breaks down boundaries between high and popular culture. The depiction of ambivalent sexualities in Gothic fictions will be examines as portrayal of domestic spaces. Various sub-forms of this genre will be studied including Irish Gothic narratives, vampire tales, horror stories and the feminine gothic. Screenings of some classic horror movies, including The Haunting (Robert Wise, 1963 ) in conjunction with this course. Texts: Shirley Jackson. The Haunting. Penguin, 1999. Stephen Jones, ed. The Mammoth Book of Vampire Stories by Women. Mammoth, 2001. J. Sheridan LeFanu. In a Glass Darkly. Oxford, 1993. --- . Uncle Silas. Penguin, 2002. Ann Radcliffe. The Romance of the Forest. Oxford, 1999. Bram Stoker. Dracula. (Any edition). Horace Walpole. The Castle of Otranto. Oxford, 1998. Secondary Reading: Elisabeth Bronfen. Over Her Dead Body: Death, Feminity and the Aesthetic. (Manchester UP, 1992). Sigmund Freud. "The Uncanny". Pelican Freud, Volume 14. (Penguin, 1985). Joseph Valente. Dracula's Crypt: Bram Stoker, Irishness and the Question of Blood. (U of Ilinois P, 2001). Walt Whitman Dr Eldrid Herrington Monday 4pm This seminar will examine Whitman's writings, from the revolutionary edition of Leaves of Grass in 1855 through to the 'deathbed' edition of his poems in 1892. Seminars will follow the innovations and opportunities his works presented to 19th-century American consciousness, from the technical achievements of his 'free verse' style to his considerations of contemporary cultural developments such as baseball. Whitman was one of the first writers to aestheticize the city; one seminar will be devoted to his treatment of New York. Leaves of Grass was constantly under scrutiny or censure for its explicit presentation of sex; we will discuss contemporary responses to Children of Adam. By contrast, his treatment of 23 homosexuality was admired by many: we will also look at contemporary writers' responses to the Calamus 'sonnet' series. Whitman's Civil War writings, Drum-Taps (1865) and Specimen Days (1882) are some of the finest writing on war; these texts will be examined by looking at the role of the photograph in his work and his involvement with Matthew Brady and Alexander Gardner (portraitists and documenters of the conflict). A consideration of the role of the photograph in 19th-century American culture will lead us to think about the larger questions of 19th-century constructions of selfhood, a subject which implicitly underpins the entire seminar. The last session will be devoted to a brief examination of Whitman's extensive influence in 20th-century literature-from the Modernists to the Beats to postmodern poets and novelists. Required Text: Whitman, Walt. Complete Poetry and Selected Prose. Ed. James E. Miller, Jr. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1959. Ulysses Professor Declan Kiberd (First Semester Only) Monday 4pm James Joyce’s masterpiece headed all recent lists on both sides of the Atlantic as the “book of the twentieth century”. This course will pursue a chapter-by-chapter reading, guiding students through its complexities and answering at least some of its challenges. Certain questions will recur: Joyce's use of epic modes; his sense of Dublin as an intimate city; his attitude to the past, to nationalism and to religion; his revolutionary use of new forms and styles, not least interior monologue; the role of the ‘heroic’ reader in decoding the text; the mixture of high art and popular culture. In the course of our work, we shall try to define just what it is that makes Ulysses the central exhibit in the story of Irish modernism, while also registering its influence on European and post-colonial writers. Essential Text: The Student’s Annotated Ulysses, ed. Declan Kiberd, Penguin Twentieth Century Classics. Recommended Reading: Stuart Gilbert, James Joyce’s Ulysses Frank Budgen, James Joyce and the Making of Ulysses Emer Nolan, James Joyce and Nationalism Hugh Kenner, Ulysses Richard Ellmann, James Joyce Ulysses on the Liffey 24 Children’s Literature Dr Jarlath Killeen (First Semester only) Tuesday 9am This course is designed to facilitate an examination of the issues surrounding the academic study of children’s literature, and its relation to the ‘adult’ canon. We will be considering the various novels as individual texts but also as comprising a possible ‘recommended reading list’ for children. We will be thinking about how children’s literature is defined, its relation to the various cultural and intellectual environments in which it is produced, the problem of the supposed didactic nature of writings produced specifically for children, and the relationship between children’s literature and other literary genres such as fairy-tale, bildungsroman, satire, etc. Students will be expected to give short presentations. 1. Carroll, Lewis, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland; and Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There, edited by Roger Lancelyn Green, (Oxford: Oxford World’s Classics, 2000). 2. Alcott, Louisa May, Little Women, edited by Elaine Showalter, (London: Penguin Classics, 1992). 3. MacDonald, George, The Princess and the Goblin, (any unabridged edition). 4. Twain, Mark, The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, edited by Lee Clark Mitchell, (Oxford: Oxford World’s Classics, 1998). 5. Sewell, Anna, Black Beauty, (any unabridged edition). 6. Wilde, Oscar, Complete Short Fiction, edited by Ian Small, (London: Penguin Classics, 1994). 7. Baum, L. Frank, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, edited by Susan Wolstenholme, (Oxford: Oxford World’s Classics, 2000). 8. Blyton, Enid, The Adventures of the Wishing Chair, (any unabridged edition). Old English Poetry for Beginners Professor Lucas Thursday 1pm This course assumes no previous knowledge of Old English Poetry. It seeks to introduce students to the context, form and content of Old English poetry, and aims to enable students to read and understand some short passages in the original language. 25 Textbook: Mitchell, Bruce, An Invitation to Old English and Anglo-Saxon England (Oxford: Blackwell, 1995, or latest edition). William Blake Professor James Mays Thursday 1pm The status of William Blake (1757-1827) is still not agreed upon. Was he a prophet or a madman? Should he be approached primarily as a visual artist or a writer? What do poems apparently as simple as "Tyger! Tyger! Burning bright" actually mean? How did his handmade books, which he produced in only handfuls of copies, come to be so influential? How has his status changed during the critical debates of the past thirty years? The course will begin with readings of Blake's lyric poems, concentrating on Songs of Innocence and of Experience, and follow his progression to the construction of mythic narratives. It will look at his relation to surrounding intellectual movements and political events (Sensibility, Enlightenment, Romanticism; American and French Revolutions), the interplay between word and image in his illustrated books, the curious emergence of his reputation -- among other things. Blake's writing makes unusual claims and commands a particular kind of authority. Required text: The Complete Writings of William Blake, ed Geoffrey Keynes (Oxford University Press Paperback). Monstrous Speculations: Film and the Gothic Dr Gerardine Meaney Friday 10am Film Screenings: Mondays, 5pm. (Arts Annex, located behind car-park 5) This course examines the historical evolution of the major non-realistic genres of the novel, film and television narrative. Tracing the persistence of gothic genres inherited from the eighteenth century, it examines the influence of key mythic and fictional configurations and the ways in which their significance changes over time. 26 The course will draw upon genre, postcolonial and feminist criticism and psychoanalytic readings of gothic, horror and science fiction texts, but will not presume existing knowledge of these areas. It will ask if these generic fictions challenge our perceived notions of literary traditions and the relationship between culture and history. While a wide range of texts will be referred to, students are expected to select and focus on one genre or theme. Required Texts: Carter, Angela The Bloody Chamber (selected stories) Dick, Phillip K. Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? Le Fanu, Sheridan Carmilla, Radcliffe, Ann The Mysteries of Udolpho Shelley, Mary Frankenstein Stoker, Bram Dracula Films (to be shown after the seminar: attendance mandatory) Bladerunner The Company of Wolves Dracula (assorted versions) Frankenstein (assorted versions) Interview with the Vampire The Matrix Rebecca Romance and Lai Ms. Michelle O’Neill Monday 4 pm Friday 10 am The mid-twelfth century saw the rise of romance, a type of narrative verse that was distinctively different from earlier epics. In romance, emphasis is placed on the manners and morals of a sophisticated courtly society, and uses the idea of all-consuming love as a motivating force for the hero’s actions. This course will explore the complex worlds of romance and lai by examining various aspects, such as their depiction of courtly society, the treatment of women and the recurring themes of magic and the supernatural. The texts will be read in Modern English prose translation. Reading list: Arthurian Romances, Chretien de Troyes, eds WW Comfort and DDR Owen (Everyman, 1975). The Lais of Marie de France, eds GS Burgess and K Busby (Penguin, 1986). The Romance of Tristan, Beroul, ed. Alan S Fedrick (Penguin, 1978). 27 The Arthurian Tradition Dr. Margaret Robson Friday 10am Arthurian literature represents one of the most important narrative cycles in European culture. This course will study a selection of the many Arthurian texts, from their pseudohistorical Celtic origins, through the developments of French chivalric romance, to what has become recognized as the canonical Arthurian text, Malory's'Mort Darthur'. We will look at some of the ways in which Arthurianism has been put to political use and will close with an examination of Arthurianism in modern, popular culture. Week 1. Introduction Week 2. History: Geoffrey of Monmouth and the chronicle tradition. Week 3. French Arthurianism: Chretien de Troyes and Marie de France. Week 4. The Alliterative Morte Arthure. Week 5. Sir Gawain and the Loathly Lady: The Wife of Bath's Tale. Week 6. Criticizing Arthur: The Anturs of Arther. Week 7. Malory 1: The historical context. Week 8. Malory 2: Arthur and political propaganda. Week 9. Modern Arthurianisms. The following comprises a list of the core texts; students will only really need to purchase a copy of Malory's Mort Darthur, the others will be available either in the library, or in photocopy form in the Student's Union. The Life of King Arthur, Wace and Lawman, eds. J. Weiss and R. Allen (Everyman, 1997). Arthurian Romances, Chretien de Troyes, eds. W.W. Comfort and D.D.R. Owen (Everyman, 1975). The Lais of Marie de France, eds. G.S. Burgess and K. Busby (Penguin, 1986). The Alliterative Morte Arthure, ed. J. Finlayson (York Medieval Texts, 1967). The Wife of Bath's Tale in Chaucer, The Canterbury Tales, preferably in The Riverside Chaucer. Ywain and Gawain, Sir Percyvell of Gales and The Anturs of Arther, ed. M. Mills (Everyman, 1992). Works, Thomas Malory, ed. E. Vinaver (OUP,1971). 28 Ulysses Dr Anthony Roche (Second Semester only) Thursday 1pm Friday 2pm This seminar will offer students the opportunity to acquire a detailed and intimate reading knowledge of Joyce's masterpiece, his 'comic epic poem in prose' centred on the sights, sounds and smells of Dublin on June 16, 1904. Students will be encouraged to develop and follow their own interests; but there will be certain minimal secondary requirements (a reading of Richard Ellmann's biography) and at least a nodding qcquaintance with some of the multifarious Joyces that have emerged over the years - Homeric Joyce, feminist Joyce, postcolonial Joyce. But the primary emphasis will be on the reading of Joyce's text and what we as interpreters bring to it, individually and collectively. Essential Text: The Student's Annotated 'Ulysses', ed. Declan Kiberd (Penguin) Recommended Reading: Harry Blamires, The New Bloomsday Book Richard Ellmann, James Joyce (rev. ed. 1982) Hugh Kenner, Ulysses Maria Tymoczko, The Irish Ulysses Emer Nolan, James Joyce and Nationalism Shakespearean Comedy and Film Dr. Philippa Sheppard Friday 4pm Film Screenings: as below This seminar will examine four Shakespearean comedies as performance scripts, not just for the theatre, but for the twentieth-century performance art form. In addition to considering the ways in which these four plays conform and depart from the generic expectations of comedy, we will look at performance history. We will analyse the choices available to modern film directors and adaptors, regarding casting, editing, textual interpretation, and design. In addition to viewing one full version of the play, we will compare specially selected brief clips from other film versions of the same play to arrive at a better understanding not only of Shakespeare and film, but also of our own society. Each new Shakespeare film represents a reshaping and repackaging of Shakespeare for its particular era and culture. We will also look at the process of adapting a literary work for the screen. 29 Course Texts: We will tackle the texts in the following order. The films are not alternatives for careful reading of the plays. William Shakespeare Love's Labour's Lost (New Penguin Shakespeare edition) Much Ado About Nothing " Twelfth Night " " The Tempest " I will be showing film versions that retain the original language. We will look at Kenneth Branagh's Love's Labour's Lost and Much Ado About Nothing, Trevor Nunn's Twelfth Night, and finally, The Tempest, either Derek Jarman's or Peter Greenaway's version, depending on availability. Note: the four films will be screened on alternate WEDNESDAYS from 4-6 p.m. in room J207, beginning on 9 October and continuing on 23 Oct, the 6 and 20 November. The dates for the screenings in the second semester: 8, 22 January, 5, 19 February. ATTENDANCE AT THESE SCREENINGS IS MANDATORY FOR THE COURSE. Gender Roles in Contemporary Film Ms Lorraine Stierle Monday 4pm (Film Screenings: Alternate Mondays at 5pm: commencing wk.2) This course aims to introduce students to some basic concepts of film theory, including a cultural studies perspective, and to apply these theories, within a broad framework, to the films screened during the course. With the emphasis on gender positioning, films are selected to facilitate discussion on race, class, star persona and ideology. While no prior knowledge of the subject is assumed, attendance at screenings will be required in order for students to participate fully in the seminar discussions. The essay written must display knowledge of the required reading. Topics to be covered: Introduction to basic film theory: Reading a film and the use of signifiers. The 'gaze' : is it always male or do films today offer a more balanced view? Melodrama: is it packaged for women viewers specifically, and if so, why? Masculinity: Roles for men, do they reflect the changing values in society? Discussion around the acceptance of violence as entertainment. Have racial stereotypes disappeared from contemporary films? Or taken on different faces? Ideology: Unpacking the relationship between film text and its cultural context. 30 Required Reading: Denzin, Norman K. (1995) Green, P. (1998), Neale S., & Smith M. (eds). (1998) Turner, Graham. (1999), The Cinematic Society, Sage, UK. Cracks in the Pedestal, U. of Mass. Press. USA. Contemporary Hollywood Cinema, Routledge,UK. Film as Social Practice, Routledge, UK. Films (to be shown after the seminar on alternate weeks: attendance mandatory) Thelma & Louise American Beauty A Time to Kill Disclosure Dickinson and her Critics. Dr Maria Stuart (Second Semester only) Friday 1pm The seminar will focus on the poems and letters of a single writer: Emily Dickinson. Yet although encouraging a close engagement with Dickinson’s work, the course will also use Dickinson as a way of exploring a more general issue, one with profound implications for any writer: how a writer is constructed and reconstructed by succeeding generations of readers. Focusing on key moments and figures in the history of Dickinson studies, the course will examine how different critical approaches have produced contrasting readings of this poet’s work. Consequently, through a close reading of one writer, the course will alert students to how flexible a literary text can be in different critical hands. Among the other critical approaches to be covered will be: The Problem of Biography (the changing face of Emily Dickinson from the New England nun of the 1890s to the feminist icon of the 1980s). Deconstructing Dickinson (the rise in interest in Dickinson as a self-conscious manipulator of language, offering texts which draw attention to their textuality). “Give Me That Old Time Religion” (Dickinson and the decline of Calvinism). Historicising Dickinson (drawing on the insights of New Historicism, recent criticism seeks to displace the image of a female recluse with one of a writer at the very centre of a culture marked by Civil War). The course will finish on the most recent development in Dickinson studies: the rise of interest in the Dickinson manuscripts. Dickinson is unique among nineteenth-century writers in that (with few exceptions) her poetry was not published in her lifetime and consequently it is her manuscripts (some composed of fragments) which remain the most authoritative basis for readings of her work. Recent web sites by Dickinson scholars such as Martha Nell Smith seek to offer all Dickinson’s readers greater access to these fragile texts, and will thus form part of our course material. 31 Required Texts: Dickinson, Emily. Poems (Reading Edition). Ed. R W Franklin. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1999. All students must have this. Dickinson, Emily. Selected Letters. Ed. Thomas H Johnson. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1958. Secondary Reading: Photocopies of particular critical essays will be available from the Students’ Union. 32 STYLE SHEET 33 Combined Departments of English STYLE SHEET INTRODUCTION The writing of essays at third level differs in several respects from other types of writing (e.g. compositions, technical reports, newspaper articles, letters). An academic essay is a formal piece of writing, which means that it must adhere to certain standards in style, layout and presentation. Your tutor will discuss with you matters of style and argument, but this sheet will explain to you what is expected of you in terms of presentation. 1. General When submitting your essay, check this list to ensure that you have done everything that is expected of you: □ spellings are correct – pay particular attention to proper names (e.g. Spenser, MacNeice, Bakhtin) □ punctuation should be clear and aid understanding □ all grammar and syntax should be correct and clear □ the essay should be easy to read and leave room for tutors’ comments; leave a large lefthand margin □ all relevant details must be included (your name, tutor’s name, essay title etc.) on the cover-sheet provided □ all quotations are accurately transcribed 2. List of works cited/bibliography One key difference between the kinds of writing you will have done before and third level essays is the need to provide sources for the texts you quote and discuss, including secondary material. In order to do this, you must keep a record of all the materials you have consulted in preparing your essay and organise them into a bibliography (also referred to as a ‘list of works cited’). This should be ready BEFORE you write your essay so that you can use it to give sources for your citations (see 3 below). You must follow the format below in all particulars, including punctuation, underlining and indentation. The bibliography should be arranged in alphabetical order by author’s name and placed at the end of your essay. How to list a book: Author’s name, surname first. Title of the book. Ed. name of editor (if applicable). Publication information (place, publisher, date). Eliot, George. Middlemarch. Ed. David Carroll. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988. 34 How to list a work in an anthology: Author’s name, surname first. “Title.” Title of anthology. Ed. Author’s name. Publication details. Page no. to page no. Example: Plath, Sylvia. “Tulips.” The Norton Anthology of Poetry. Ed. Alexander Allison, et. al. New York: Norton, 1983. 1348-9. How to list an article in a journal: Author’s name, surname first. “Title of the article.” Periodical title volume number (date): page no. to page no. Example: McLeod, Randall. “Unemending Shakespeare’s Sonnet 111.” Studies in English Literature 21 (1981): 75-96. How to list an essay in a book: Author’s name, surname first. “Title of essay.” Title of book. Ed. name. Publication details. Page no. to page no. Example: Wayne, Valerie. “Historical Differences: Misogyny and Othello.” The Matter of Difference: Materialist Feminist Criticism of Shakespeare. Ed. Valerie Wayne. Hemel Hempstead, 1991. 153-79. 3. How to key your citations to the bibliography: Your quotations should be relevant and support your argument by providing a specific illustration of a point or an idea. There are basically three types of citation which will require supporting references: a. Direct quotation; this should always be precise in all details (including spelling, punctuation and lineation, where relevant), and include an accurate page reference. b. Close paraphrase and citation of information should also be accurate, and should be accompanied by a page-range. c. Loose paraphrase or general ascriptions of points of view should be accompanied by a reference to a source text. If your ‘list of works cited’ is correct and complete, placing accurate references for quotations and arguments in the body of your essay will be simple. The surname and page reference is sufficient (Example: Wayne, 156.). Quotations must be exact in every detail. The citation of the source should follow the quotation and must be placed in brackets. Remember, not to cite your sources exposes you to the charge of PLAGIARISM which may result in deduction of marks and/or disciplinary action. Titles of books should be underlined. The full citations for the examples given here can be found in section 4, set out as they would be in a full bibliography. 35 4. How to quote passages from PROSE and key your quotations to the bibliography: (a) Short quotations (less than 4 lines of prose) should be placed in quotation marks within the text: Middlemarch’s opening sentence is simple, but effective: “Miss Brooke had that kind of beauty which seems to be thrown into relief by poor dress.” (Eliot, 7) Longer quotations (five lines or more typed) should be indented from the margin and must not have quotation marks: In “The Yellow Wallpaper”, Charlotte Perkins Gilman uses a fragmented style to convey her central character’s mental fragility. For example: There were greenhouses, too, but they are all broken now. There was legal trouble, I believe, something about the heirs and co-heirs; anyhow, the place has been empty for years. That spoils my ghostliness, I am afraid, but I don’t care – there is something strange about the house – I can feel it. (155) NB. Because the sentence which introduces the quotation identifies the source, there is no need to spell it out again in the citation. (b) How to quote POETRY and key your quotations to the bibliography: Short quotations – up to 3 lines - may be included within the text. Citations use LINE numbers not page references: Ben Jonson quickly introduces us to the twin themes of his elegy on Shakespeare by referring to his “book and fame” (“To the Memory of My Beloved”, 2). Longer quotations must be indented from the margin. You must follow the layout of the poem that you are citing. Jonson signals the fact that Shakespeare is exceptional by using exclamation and by suggesting that he is the best of poets: I therefore will begin. Soul of the age! The applause! Delight! The wonder of our stage! My Shakespeare, rise; I will not lodge thee by Chaucer or Spenser, or bid Beaumont lie A little further to make thee a room: (“To the Memory of My Beloved”, 17-21) (c) How to quote passages from DRAMA and key your quotation to the bibliography: The same rules on length apply here as with poetry and prose (above). However, if quoting dialogue between two or more characters, you must indent the quotation, supplying the characters’ names, following by a period (full stop): Throughout Othello Iago proves to be a master manipulator of language, using insinuation and inference to plant suspicion in Othello’s mind: 36 IAGO. OTH. IAGO. OTH. IAGO. Ha! I like not that. What dost thou say? Nothing, my lord; or if – I know not what. Was not that Cassio parted from my wife? Cassio, my lord? No, sure I cannot think it That he would steal away so guilty-like, Seeing you coming. OTH. I do believe 'twas he. (3.3.34-40) The citation must include act, scene and line numbers, as in the example above. NOTE: when you quote from Shakespeare or any other dramatist make sure that you state the edition used. This will appear in your bibliography as below*. It should always be a ‘reputable’ edition rather than, for example, a schools’ edition. (d) How to quote from Online sources and key your quotations to the bibliography: The example below includes a quotation from a book. However, the source of the quotation is not a printed book but an electronic version online. Harriet Jacobs begins her account of her life with a dramatic image of childhood innocence: “I WAS [sic] born a slave; but I never knew it till six years of happy childhood had passed away” (Jacobs ch.1). Note the accuracy of the quotation—the use of [sic] indicates that you are quoting accurately from the text and that the capitalised “WAS” is not your typographical error. This is a text taken from a web site. In order to cite it correctly you must enter information as detailed as that required for a print source and listed above. However, your source is the web site and you must seek to include: a) date of the last update of the site b) date you accessed the site c) address of the site, enclosed in angle brackets, < > (see example in the bibliography section below) If the information you require is not displayed on the site, include what is listed. In doing so, you are making your sources available to your reader as you make printed books available by listing editions and publication details. The “date of access” is important. Sites can be changed relatively easily and your tutor/seminar leader might open a site which has changed significantly from the one you used a day or two earlier. Finally, it is advisable to print the material you use from a web site so that you can verify your source if the site cannot be located by your tutor/seminar leader. 5. Bibliography (for the examples in section 4, above) Eliot, George. Middlemarch. Ed. David Carroll. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1988. Gilman, Charlotte Perkins. “The Yellow Wallpaper.” The Oxford Book of American Short Stories. Ed. Joyce Carol Oates. Oxford, Oxford UP, 1994. 154-69. Jacobs, Harriet. Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, Written by Herself. Boston, 1861. 18 Dec. 1997. 25 July 200 <http://xroads.virginia.edu/~HYPER/JACOBS/hjhome.htm> 37 Jonson, Ben. “To the Memory of My Beloved.” The Norton Anthology of Poetry. Ed. Alexander Allison, et.al. New York, Norton, 1983. 1673-38. Shakespeare, William. Othello. Ed. Norman Sanders. Cambridge, Cambridge UP, 1984. NOTE: The bold-faced type in Sections 2, 3, 4 and 5 is used for emphasis and is not required in your work. 6. A few further points: If you are citing more than one text by the same author, you must i. make clear which one you are referring to in your citation. For example, if you are using two novels by George Eliot, your citations must make a clear distinction, i.e. (Eliot, Middlemarch, 55) or (Eliot, Mill on the Floss, 78). ii. list them in date order in your list of bibliography, using the following format: Eliot, George. The Mill on the Floss. Ed. A.S.Byatt. Harmondsworth, Penguin, 1979. ---. Middlemarch. Ed. David Carroll. Oxford, Oxford UP, 1988. You may abbreviate titles for convenience in your citations, but never in the bibliography. For example, The Mill on the Floss could become simply Mill, or Jonson’s “To the Memory of My Beloved” might become “Memory.” However, these abbreviations must be clear and consistent. Some of the texts you will be using will be taken from collections or anthologies. Rather than writing out the full details for each item you cite, you could give one entry for the anthology and then key the other entries to it. For example, if you are writing about Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s “The Yellow Wallpaper” and Kate Chopin’s “The Storm”, your list of works cited would look like this: Chopin, Kate. “The Storm.” Oates, 130-35. Gilman, Charlotte Perkins. “The Yellow Wallpaper.” Oates, 154-69. Oates, Joyce Carol, ed. The Oxford Book of American Short Stories. Oxford, Oxford UP, 1994. In preparing your essays, you should make full use of the resources on offer in the Library. These include the Library’s web site. Students of English will find a range of relevant information and texts available on the Electronic Library site. For example, you might make use of the Oxford English Dictionary (OED), Annotated Bibliography of English (ABES) or Modern Language Association Bibliography (MLA). Primary texts and scholarly articles are available online on sites such as JSTOR, LION, and SwetsNet Navigator. All these can be accessed from the Library’s home address:<http://www.ucd.ie/~library/> If you have any questions about any aspect of this “Style Sheet,” you should ask your tutor/seminar leader for guidance and advice. oOo 38