Does the European Union need a formal constitution

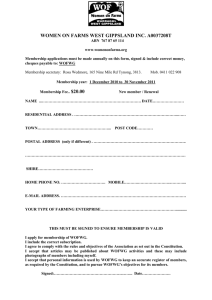

advertisement

Does the European Union need a formal constitution? European constitutional Law Aristotle University of Thessaloniki 2016-03-03 Johanna Norén Does the European Union need a formal constitution? by Johanna Norén Sweden 1 Does the European Union need a formal constitution? European constitutional Law Aristotle University of Thessaloniki 2016-03-03 Johanna Norén 1.1 Introduction ....................................................................................................................................... 3 2.1 A formal constitution......................................................................................................................... 3 3.1 What is the European Union? ............................................................................................................ 4 3.2 Rulings by the European Court of Justice ..................................................................................... 5 4.1 The power structure ........................................................................................................................... 6 4.2 Legislative process ........................................................................................................................ 6 4.3 The democratic deficit .................................................................................................................. 7 5.1 Does the structure of the EU need a makeover?................................................................................ 8 5.2 Democracy .................................................................................................................................... 8 5.3 Executive Federalism .................................................................................................................... 9 5.3 A structural makeover ................................................................................................................. 11 5.4 The Draft Constitution ................................................................................................................ 11 6.1 Conclusion ....................................................................................................................................... 12 Bibliography .......................................................................................................................................... 14 Articles and Publications .............................................................................................................. 14 Case-law ....................................................................................................................................... 14 2 Does the European Union need a formal constitution? European constitutional Law Aristotle University of Thessaloniki 2016-03-03 Johanna Norén Does the European Union need a formal constitution? 1.1 Introduction In this essay I will discuss the potential need for a formal constitution within the European union. The European Union holds a unique position in the world. It has gone from the Coal and Steel Community established in 1951 with only six members, to today’s Union with 27 member states and with an extensive competence of policy making. The Union is established by a number of treaties. In order to answer the question if there is a need for a formal constitution rather then the existing treaties I will start by answering this questions, what defines a formal constitution and what function does it fill? What is the European Union and what changes would a formal constitution result in? I will then discuss some problems existing within the European Union in the present system and whether these problems indicate a need for a formal constitution. 2.1 A formal constitution A formal constitution is the highest and fundamental law of a state and has the aim to organize the government of this entity. It can be written or unwritten. That it is the fundamental law means that any legal act that goes against the constitution is void. In the role of organizing the government it will include regulation on how the governing organs relate to each other, what power they have, how they should be elected and so on. The constitution should also regulate the extent and manner of the exercise of sovereign powers. This means that it will include rules on how to make legislation. A constitution derives from the authority of the governed and is agreed upon by the people. And finally it will include a bill of rights.1 A constitution will generally be harder and more complicated to change than a ”normal” law. In defining the term formal constitution, the type of entity that it is related to is a nation or a state. Not an international organization or other political unifications. Does this mean that only states can have a formal constitution? No, a Union like the EU could in its present state, not being a federation, defiantly fill the criteria for having a formal constitution. There is nothing in the definition that demands the entity in question to be a state. The question is instead why an entity, which is not a state, would need one. 1 Piris, Does the European Union have a constitution ? Does it need one ? p.3-4 3 Does the European Union need a formal constitution? European constitutional Law Aristotle University of Thessaloniki 2016-03-03 Johanna Norén 3.1 What is the European Union? The EU is not a state, and is appears to hold much more competence then the average international organization, so what is it? This is a crucial question in order to determine whether or not it needs a formal constitution. The European Union is to be described as a political system. According to the definition of such it shall have a clearly defined and stable set of institutions for collective decision making and a rules for governing the relations between this institution. The EU fills this criterion. The main institutions with in the EU, the Commission, the Council, the Parliament and the Court of Justice is both stabile and clearly defined and the treaties well qualifies as a set of rules that governs the relation between the institutions. Secondly a political system has citizens that seek to realize their political requests through the political system. This can be directly or through for instance interest groups or political parties. With in the competence of the European Union this is also fulfilled. There are a number of lobby-groups that seek their political desires through the EU, and of cause most importantly, the national governments of the member states. Thirdly, the decisions made with in the political system have a significant impact on in the distribution of economical resources and on social and political values with in the system. Looking at the competence that lies within the EU, this criterion is definitely fulfilled. The internal market, environment, education and foreign policy, are just a few of the areas were EU decision-making will have a significant impact. Number Four, there is a continuing interaction between the political outputs, new demands of the system and new decisions. This is just like the other criteria fulfilled, the political process within the Union is continues and the interaction between its institutions and national governments occurs on a regular basis.2 The European Union is a political system but not a state. The main reason why the Union is not to be considered to be a state is the following; the Union has no competence when is comes to police and military-forces. There is no internal penal-system, and the union does not have what the Germans call kompetenz- kompetenz. Kompetenz- kompetenz stand for the competence to determine ones competence. The Union on the other hand only has so much competence that the member states decides to give it. Maybe most importantly in the question of statehood, the Union has not claimed to be one. Before there is such an ambition, the union will hardly be to consider a state. 3 The character of the Union is important to determine in order to see the reason for why the question about a formal constitution has been awakened. With in international organizations on a strict inter-governmental level, one would not hear the demand of a formal constitution. This since a formal constitution is normally seen in the context of states. The European Union being much stronger and 2 3 Hix, The Political System of the European Union, p. 3-5. Van Gerven, The European Union, A Policy of States and Peoples, p. 38 4 Does the European Union need a formal constitution? European constitutional Law Aristotle University of Thessaloniki 2016-03-03 Johanna Norén more power full in relation to competence than other international organizations today, does explain why there is a discussion about a formal constitution. The similarities of a federal state are many and the EU decision-making has a great impact in the member states With the special character of the European Union in mind, lets investigate the potential need for a formal constitution. 3.2 Rulings by the European Court of Justice The treaties establishing the EU do not fulfil the criteria for a formal constitution, but within the political system there are elements that do make the system “constitutional-like”. This element does not directly derive from the treaties, but from the European Court of Justices interpretation of the treaties. One of these elements is the supremacy of the EC law over domestic law. This supremacy is not stated within the treaties. In the case of Costa v. ENEL the trial gave a preliminary ruling on a question were the domestic law was in contradiction with the EC law. 4 The court argued that when entering the EC treaty the member states limited their own sovereignty by transferring some of their sovereign rights to the Community. Therefore the power exercised by the community cannot vary from state to state, because of domestic legislation. Such an order would jeopardize the purpose with the Community stated in article 5 and enable a kind of discrimination that is forbidden in article 7. Another element that gives the Union an “constitution-like”character is the direct effect. The fact that some treaty articles and also directives can have direct effect is not stated in the treaties. This is also a result of the interpretation of the ECJ. In the Van Gend en Loos case the court came to the conclusion that some articles of the EC treaty have direct effect, meaning that citizens of the member states have the right to call upon EC law in national courts.5 In this case the court argued that the European Community creates a new legal system with in the public international law, that after the transfer of a part of the states sovereign rights to the Community applies not only to the state, but also to its citizens. The result of opening up for direct effect was that the treaties gained more characteristics of a constitution than those of a treaty. In international law, the subject is the state, not its citizens. Meaning that the citizens cannot call upon the convention in question unless it has been incorporated in to domestic law.6 This leaves the Community in an interesting position. It is not a state but a political system that has been created by sovereign states, each giving up some of its sovereignty in favour of the Community. The treaties was set up and entered by states according to the principles of public international law where the states are the subject. Yet, they now have a function that goes 4 Costa v. ENEL, case 6/64 1964, ECR 585 Van Gend en Loos v. Nederlandse Adminisrtatie der Belastingen, case 26/62 1963, ECR 1 6 Hix, The Political System of the European Union p. 121-122 5 5 Does the European Union need a formal constitution? European constitutional Law Aristotle University of Thessaloniki 2016-03-03 Johanna Norén beyond that of a normal treaty. So maybe the step from treaties to a constitution would not necessarily be that big? 4.1 The power structure The main institutions of the EU consist of the Commission, the Council of Ministers, the European Parliament and the European Court of Justice. Their functions and responsibilities are regulated in the EC treaty. A deeper analysis of the institutions is not necessary here, but some characteristics are important to point out. The Council consists of one member on minister level from each member country. The members of the council changes of cause depending on what topic that is being handled. This is stated in the EC treaty article 203. The Commission consists as stated in article 213, of at least one, but no more than two members from each member state. They do not however represent their home countries, but are supposed to act in the best interest of the Union. It is the Commission that makes propositions about new legislation. The sits in the European Parliament is distributed between the member states in accordance with the size of each member states population, article 189 and 190 of the EC-charter. The Parliament holds a weaker possession than a national parliament normally does. It has no right of proposing new legislation and in some cases it cannot disqualify a policy in the making since it does not have to be consulted in every case. In this essay, the most interesting topic regarding the governing institutions is their relation to each other and how much power each institution has to affect the policymaking. 4.2 Legislative process The policy-making within the Union is mainly made by executive actors, meaning the Council and the Commission, yet the position of the European Parliament is not insignificant. There are four different types of legislative possesses, Consulting, Cooperation, Assent and Co-decision proceedings. Under the procedure of co-decision and assent procedures, the Parliament has the power to exercise veto. This is not possible in the other two procedures. The number of readings in the Parliament and the Council also change in accordance with what procedure that is used. For consultation and assent procedures there are single readings, for cooperation procedure there are two and finally for the codecision procedure there are potentially three. Further on, there is a different procedure for the annual budget, and for policy making under pillar two and three the procedure is mostly intergovernmental.7 7 Nugent, The Government and Politics of the European Union, page 333 6 Does the European Union need a formal constitution? European constitutional Law Aristotle University of Thessaloniki 2016-03-03 Johanna Norén The role of the European parliament in this process is in many ways advising. In the first and second reading the proposal is sent to the Parliament who can reject, accept or make amendments. The Commission how ever is not always forced to follow the decisions of the Parliament. In Co-decision procedural the Parliament has the opportunity to reject a proposition, but in the Cooperation and the Consulting procedures the Commission can choose to look beyond the opinions of the Parliament. In the legislative process the main powers lie within the Commission and the Council. Even though the influence of the Parliament has increased over the years, it is not equal with that of the other two institutions. In international law, where the states are the subject, it is the norm that the governments if the contracting parties are the active parts of setting up the treaties. The EU is, as has already been mentioned, different. The regulations issued with in the union are directly applicable in the member states and directives has even though they should be implemented in to domestic law, direct effect under certain conditions. The area where the Community has competence to issue legislation is extensive and has impact in significant parts of the societies of the Union. This leads in on what is called the democratic deficit of the EU. 4.3 The democratic deficit The democratic deficit has been debated with in the Union since the 1980s, yet there is no absolute definition for it. Generally the term is used in regard of the relationship between the reduced powers of the national parliaments in favour of the Community. This should of cause not come as a surprise to anyone; this is one of the basic features of the Community. The issue in concern is not the actual transfer of power though, but the way that power is being exercised within the Community. A part of this is the compared to national parliaments rather week position of the European Parliament and the slim possibilities for the citizens to directly effect the Union by voting. The Psychological distance between the Union and its citizens and the fact that the Union policy making often is considered to go against the wish of the citizens is also a part of the democratic deficit.8 There is however no clear solution to this problem. It can even be argue that the democratic deficit is not in fact a problem at all, depending on from which angel the issue is addressed. As stated before, the European Union has a peculiar position somewhere between a federation and an international organization. And since the EU does not have the character of a state, can it be expected 8 Hix, The Political system of The European Union, page 177 7 Does the European Union need a formal constitution? European constitutional Law Aristotle University of Thessaloniki 2016-03-03 Johanna Norén to reach the same level of democracy as a state? Given the extent of the power that has been given to the union, one could defiantly expect a high level of democracy. The legislative power of the Community is strong, EC law is held as superior to domestic law, and the arias where the EC can make legislation are many. Therefore the democratic structure of the EU could need a reformation. The question is however, what would this reformation look like and is a formal constitution the solution? 5.1 Does the structure of the EU need a makeover? As stated above, a formal constitution would not necessary mean a great difference from the system we have today with treaties establishing the European Union. But that does not mean that there is not a need for a great difference. The purpose of this essay is to determine whether or not there is a need for a constitution. Up until now, I have focused on the structure of the EU today, and weather or not EU with its present form is in need of a formal constitution. I would say that the answer is no. As a formal constitution could be imposed with out any major changes there would in my opinion mostly be a name change. A much more interesting question to ask is what need we do have with in the union and what changes that could be made in order to satisfy that need. 5.2 Democracy The main democratic problem with the EU today is that the decision-making still has too much character of that of an international organization, yet its power goes far beyond what such an organization would normally have. I will in this chapter point out some of the democratic problems that can be found in the present system. The principle of democracy with in the Union is stated in art. 6(1) of the EU-treaty. The article however can be considered to be rather vague since it does not include any concrete implications for its institutional materialization.9 Looking at how the power structure with in the Union is built up we found that the democratic legitimacy is mainly resting on the national parliaments. This since they are controlling the national governments as they are acting in the Council. The national parliaments are also the once who are the sovereign actors in constitutional matters ratifying treaty reforms, in theory. In practice, it is the national governments that are involved in the regular procedures. This gives rice to 9 Von Bogdandy and Bast (editors), Principles of European Constitutional Law, article by Philipp Dunn p. 270 8 Does the European Union need a formal constitution? European constitutional Law Aristotle University of Thessaloniki 2016-03-03 Johanna Norén some problems. The members of national parliament this way lack insight information, due to the fact that they do not participate in the policy-making procedures, and often also in-depth experience. This makes the control of the national governments actions harder. Another issue is that the decision making process often are based on confidential negotiations, which of cause make the task of control hard for the national parliament.10 5.3 Executive Federalism The role of the European Parliament is often brought up as an example of democratic problem, one part of what is called the democratic deficit is the week position of the parliament. Being the only body within the EU that is directly elected by the citizens of the member states, one could easily argue that a weak position of the parliament means a weak democracy with in the Union. In reality the situation is more complicated then this. Philipp Dann writes for instance of the European Union as being a system of executive federalism.11 The executive federalism can be considered to have three main characteristics. In is rooted in a vertical structure of interwoven competence. For the EU, this means that the policy making is exercised on a federal level, wile as the implementation is conducted at the level of the member states. The article 10 of the EC treaty is the legal foundation of this order. This article states the duty of loyalty in regard of fulfilling the obligations that arises though the treaty. In short, the Union lacks competence of implementing EU law and that responsibility rests on the member states. The next characteristic of executive federalism is the existence of an institution that organizes the necessary co-operation that the first characteristic demands. With a system of interwoven competence it is necessary with co-operation in many different levels, in the process of negotiation law, when implementing the law, and also when reviewing the law, this since the competences of this actions are put on different actors. Therefore co-operation between the two levels, the Union and the member states is essential, as well as co-operation with in the levels. The institution that organizes the co-operation is the Council of ministers. The third characteristic is a decisionmaking mode of consensus facilitates co-operation in the Council and beyond.12 10 Von Bogdandy and Bast (editors), Principles of European Constitutional Law, article by Philipp Dunn, p. 270 -272 11 Von Bogdandy and Bast (editores), Principles of European Constitutional Law, article by Philipp Dunn p 237 12 Von Bogdandy and Bast (editors), Principles of European Constitutional Law, article by Philipp Dunn p. 238 9 Does the European Union need a formal constitution? European constitutional Law Aristotle University of Thessaloniki 2016-03-03 Johanna Norén Looking at the democratic problems with in the Union in the light of executive federalism, adds another dimension to the issue. Starting with the role of the national parliaments, a greater possibility for them to control their government in their actions with in the union might not necessarily be of the advantage of the Union. With the need of consensus in decision-making, and the great need of co-operation between and within the levels, a to strict control of the governments could lead to a constant blocking of procedures. This is of cause not preferable. When it comes to the European Parliament there are also problems when looked at in the light of executive federalism. Since the function of a parliament is to serve as a public forum of society a problem arises when it comes to the European Parliament.13 There are only very loose European parties. And they do not provide any specific European programs. This means that focus in national election often is dominated by national topics. Brining national topics forward is of cause important for the individual voter, but it does not compensate for the lack of focus on the Union as a whole. The EU being a political system of its own needs a political program with focus on the Union as such. Another problem and maybe a greater one, is that of the role of a parliament with in the structure of an executive federalism. The whole system works by nature against a parameterization. The Council appoints the Commission and even though the Parliament has got some to say when it comes to this, the main power still rests with in the competence of the Council. The council is on top is virtually unreachable for the Parliament. The situation with Council and Commission being partners in law making and executive functions fits well in the system of executive federalism and is based on the intergovernmental nature of political system of the EU.14 So what conclusions can be made from this? Looking at the democratic problems I have stated earlier in the light of the EU having the structure of executive federalism the problems seen unchangeable. A greater transparency in order for national parliaments to better control their governments and there by strengthen the connection back to the people, could lead to a situation where the whole decision-making procedure being crippled. This is due to the system of consensus. If the national parliaments played a bigger role, negotiations and compromises could not be handled as smoothly. Strengthening the European Parliament could also prove difficult since the system by nature does not go hand in hand with a parliamentary system. The whole system with focus on co-operation and division of power in legislative matters is not constructed to include a strong Parliament. Also the problems with election of the members of parliament and the weak European parties gives rise to the question whether a stronger Parliament would necessarily mean a more democratic Union. 13 Von Bogdandy and Bast (editors), Principles of European Constitutional Law, article by Philipp Dunn p. 273 14 Von Bogdandy and Bast (editors), Principles of European Constitutional Law, article by Philipp Dunn p. 247 10 Does the European Union need a formal constitution? European constitutional Law Aristotle University of Thessaloniki 2016-03-03 Johanna Norén 5.4 A structural makeover With the system today, there are may problems and as stated above, mort of them related the fact that the EU has gone from being a intergovernmental organization to something in the middle of this and a federation. The structure therefore is in need for a change. If this change should be made though creating a formal constitution of not remains yet to decide. In this chapter I will have a brief look at the draft constitution that has not yet been able to set in to action and determine if the changes that would be made by it is sufficient, or if maybe other or greater changes could be motivated. I can of cause not cover all aspects of the draft constitution, but will focus on the parts that are related to the problems I have been discussing so far. In the process of creating the draft constitution, the aim was to resolve a number of issues; 1) How to create a clear and precise division of competences between the Union and the Member States, 2) how to enforce the principle of subsidiary, this with a specific attention to weather the national parliaments should be able to block proposed Community legislation under certain conditions, 3) whether the Charter of Human Rights should be made binding to the Member States and become part of the Constitution, 4) how to simplify the Unions instruments and decision-making procedures, 5) how to reorganize the legislative and executive branches of the Union to enhance the Union’s democratic legitimacy and finally 6) how to increase the role of national parliaments in the European architecture.15 These are all issues of great importance and in need of reformation. The question is does the draft constitution provide this information? 5.5 The Draft Constitution The draft constitution marks an end to the three-pillar system we have today. This does not mean that the questions previously dealt with under the second and third pillar will now be handled in the same way as the once belonging to the first pillar. There will still be a difference in how much competence the Union has in different questions. And when it comes to the distribution of power between the Union and the member states, not many changes were proposed in the draft Constitution. The principles of conferral, subsidiary and proportionality will as they are today be the main guiding policies. In reality the changes proposed in the area of distribution of power does not change the character of the EU either way, not closer to an intergovernmental organization and not a federation. 16 The problematic middle status therefore remains. 15 16 van Gerven, The European. Union, Apolicy of States and Peoples, p. 257 van Gerven, The European. Union, Apolicy of States and Peoples, p. 273-276 11 Does the European Union need a formal constitution? European constitutional Law Aristotle University of Thessaloniki 2016-03-03 Johanna Norén When it comes to democratic legitimacy the proposed situation would be as follows; the European Parliament will represent the citizens on Union level, the member states will be represented in the Council of Ministers and the Commission will promote the general European interest. So far no changes from the present system obviously. One important change is proposed though; the Council will just like the Parliament meat in public. This however will only occur when they examine and adopt a legislative proposal. The balance of power between the institutions will not change with the draft Constitution, but the different institution would be better defined, which means a stronger legitimacy since it is vital that the function of each institution is clearly outlined. 17 As stated it is not possible to go in to any details of the draft constitution in this essay, but in the light of the structural problems I have discussed earlier, it is my opinion that the draft Constitution does not resolve this issues. 6.1 Conclusion In order to answer the question, whether or not the European Union needs a formal constitution, lets look back on the definition of a formal constitution. The aim of such is to organize the government of an entity, be the highest and fundamental law, regulate the extent and manner of exercise of sovereign powers, derive from the authority of the governed and be agreed upon by the people and include a bill of rights. Is there a need of this with in the EU? In many ways, the treaties establishing the EU does already live up to this, and in combination with certain rulings by the European Cont of Justice, they do in many ways have the character of a constitution. The question is therefore what a formal constitution could do for the Union that the treaties do not already contribute with. There are problems with in the structure of the EU today. The EU is a political system without being a state. It has the character of an intergovernmental organization as well as a federation and its legislative powers are extensive. This factors has resulted in certain democratic difficulties. For a purely intergovernmental organization the democracy level is fine, the member states are represented by the national governments, which are controlled by the national parliament who are representing the citizens of the member states. But because of the amount of competence that lies within the Union, it is my opinion that a higher level of democracy is needed. Would a formal constitution be able to create this? Möllers gives an interesting view of the different functions of a constitution. By looking at the history of existing federations, he out lines two different kinds of constitutions. One who will mean a founding of a completely new system, and an other who places the juridification of an already existing 17 van Gerven, The European. Union, Apolicy of States and Peoples, p. 292 12 Does the European Union need a formal constitution? European constitutional Law Aristotle University of Thessaloniki 2016-03-03 Johanna Norén governmental system in its center. The first form of constitution the addresses are the people that are subject to the new authority, examples of this type of constitution is that of France and the United States. Both these countries constitutions were constructed as a result of revolution, and the result being a foundation of new systems is logical. The second form of constitution was used in Germany and Great Britain and the result of unification rather then revolution. This explains why the both constitutions got the form of power shaping and remodelling of an existing system. 18 These two forms of constitution are interesting when discussing the EU. The EU does at the moment not have a formal constitution and with the power-shaping form of constitution would clarify and limit the power structure. The problem with this form of constitution is that it does not necessarily lead to a more democratic system. A clarified and limited power structure does not automatically mean a democratic power structure. The type of constitution that creates a new system would more likely lead to a more democratic system. Unfortunately it is hardly a realistic alternative. To completely reform the Union and create a new legal order is a too improbable scenario. Further more the system that this kind of constitution creates is with the focus on the people who would be subject to the new authority. In the context of European Union, this would mean the citizens of all the member states. But since the EU is not one state but a political system consisting of a number of sovereign member states this would create problems. In their pure forms, neither of the two types of constitutions seems to be possible to use with in the EU. By this we reach the following conclusion; from a democratic point of view there is a need for a reformation of the present system. From a constitutional point of view, it is possible for an entity, which is not a state to form a constitution. But in my opinion, a formal constitution without being a state would not change democratic flaws of the EU. In an intergovernmental organisation which the EU still is, despite its federal characteristics, there is not possible to uphold the same level of democracy as within a state. I can therefore not se that the European Union needs a formal constitution. Some of the democratic issues can of cause be adjusted, by for instance making the policymaking process in the council more transparent – like proposed in the draft constitution. 18 Von Bogdandy and Bast (editores), Principles of European Constitutional Law, article by Chistoph Möllers p. 185-191 13 Does the European Union need a formal constitution? European constitutional Law Aristotle University of Thessaloniki 2016-03-03 Johanna Norén Bibliography Articles and Publications Piris, Jean-Claude, Does the European Union have a constitution? Does it need one? Harvard Law School, Cambridge, 2000 Hix, Simon, The Political System of the European Union, 2nd addition, London 2005 Nugent, The Government and Politics of the European Union, 6th addition, London, 2006 Van Gerven, The European Union, A Policy of States and Peoples, Oxford, 2005 Von Bogdandy and Bast (editors), Principles of European Constitutional Law, volume 8, Oxford, 2007 Case-law Van Gend en Loos v. Nederlandse Adminisrtatie der Belastingen, case 26/62 1963, ECR 1 Costa v. ENEL, case 6/64 1964, ECR 585 14