Demographics of, and services to, kāpo Māori in New Zealand

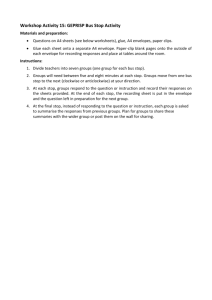

advertisement