Calvin & Servetus - Evangelical Tracts

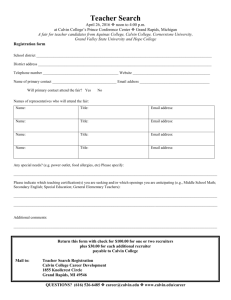

advertisement