the First Amendment and the defense of the

advertisement

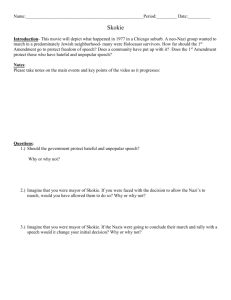

THE FIRST AMENDMENT AND DEFENSE OF THE UNPOPULAR Anthony D. Romero, ACLU Amherst College March 29, 2004 (SPEECH PREPARED BUT NOT DELIVERED) I am honored to be here today and thank you for the invitation. Apparently Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia has preceded me in this lecture series. This is as it should be. As an “originalist” he should go first. And as an “actualist” I should go next. That way, you will know what is actually happening in the realm of the Constitution and the Bill of Rights. In my lecture today I would like to focus on the evolution of the First Amendment and the defense of the unpopular. Yes, the First Amendment has indeed evolved, from a mostly empty promise to a vigorous support for an expanding universe of civil liberties. This should surprise no one, for the Founders of the republic clearly regarded the American Revolution as a long-term experiment testing the limits of personal freedom. The historian Joseph Ellis recently observed that: “At the very birth of the republic, an open-ended mandate for individual rights was inscribed into the DNA of the body politics, with implications that such rights would expand over time.” And so they have. And the ACLU, I am proud to say, has played a leading role in that expansion. This expansion of civil liberties would not have occurred were it not for the existence of an absolute right to free speech, including the free expression of ideas with which we heartily disagree. The defense of unpopular views is, therefore, the most critical test and the one true measure of a free people. And so it should be, for a people cannot be free unless they are able to express themselves freely, to associate freely, to petition the government freely, and to pray freely— or to be free not to pray at all. The First Amendment establishes the essential condition for a democratic society. That is, a free marketplace of ideas to which everyone contributes and from which everyone draws information and inspiration. In this sense, the free speech guarantee encompasses two rights—first, the right to speak; and second, the right to listen. Usually when we discuss the merits of free speech we are referring to the speaker’s right to express his or her views without fear of prosecution or censorship. But consider the fact that there is also a “listener’s right.” That is, the right each of us has to hear different ideas and opinions, including and especially those with which we might disagree. The listener’s right to hear is an essential component of free speech. After all, the exercise of free speech requires an audience—one that attends freely and listens freely. Moreover, by exercising our right to listen, we are strengthening the foundation on which other democratic values rest. This is especially the case when we listen to views that are 1 of 9 opposed to our own. For it is exactly in such instances that we learn the value of tolerance that is the real and most critical lesson of the First Amendment. THE FIRST AMENDMENT AND WORLD WAR I The ACLU, as you know, is in the business of defending unpopular causes and unpopular defendants. We have been in this business for nearly nine decades—ever since Roger Baldwin, the organization’s founder and leader for the first thirty years, decided that the defense of the rights of everyone, the downtrodden and even the advocates of the most hateful ideas, would be our guiding principle. This principle was not a foregone conclusion. When the National Civil Liberties Bureau was first organized during World War I it defended conscientious objectors and antiwar protestors. The war was widely unpopular. The country was also seething with pent-up economic, religious and ethnic conflicts following decades of rapid change caused by industrialization, urbanization and immigration. The combined result was an unprecedented wave of intolerance, repression, and violence. The government responded with a national crusade to enforce patriotism and political conformity, sweeping aside free speech and due process. President Woodrow Wilson himself led the attack on free speech, declaring that the “authority to exercise censorship is absolutely necessary to the public safety.” And because the most vocal of the war critics were socialists, anarchists, labor radicals, and recent immigrants, the public saw free speech as a pretext for everything “un-American.” Roger Baldwin, Crystal Eastman, Jane Addams and others, who had been galvanized into action by wartime repression, faced a serious challenge. The challenge only grew in the war’s aftermath when the Supreme Court— which had been silent in the face of wartime repression of civil liberties—finally addressed the question of free speech in a time of national emergency. Unfortunately, the Court’s rulings, four months after the war’s end, were a resounding defeat for civil liberty. In three separate decisions, the majority upheld the government’s suppression of dissenting views. In the first of these, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes established a “clear and present danger” test that became the first legal limitation on the absolute right of free speech. DEFENSE OF RACIST VIEWS AND GROUPS Baldwin and others who were galvanized into action during the war were defending people and ideas they for the most part sympathized with and supported. This is not to minimize the courage, persistence and ingenuity it took to oppose government actions at the time. However, as critical as these challenges were, the real test came later, during the nineteen-twenties, when the ACLU had to decide whether the First Amendment applied not only to dissenting views it supported, but also to views it strongly opposed. At the time, the Ku Klux Klan was riding high and anti-Semitic views were publicized by such wellknown persons as Henry Ford. Liberals began to fight back and in a number of cases won restrictions on racist speech. At that point the newly renamed American Civil Liberties Union had to take a position on whether or not the First Amendment applied across-the-board, even and perhaps especially, to views the young organization itself found abhorrent. 2 of 9 For if the First Amendment applied across-the-board, then the ACLU would have to tell its beleaguered allies in the NAACP that it supported the rights of the Klan. It would also have to tell its Jewish friends that it supported the rights of anti-Semites. And it would have to tell its communist clients on the radical left that it supported free speech for right-wing reactionaries. Thus it was in the context of disputes with allies and clients that the ACLU sharpened its position on free speech. The position that eventually emerged was a ringing endorsement of the First Amendment. When Henry Ford’s newspaper, the Dearborn Independent, published a series of wildly anti-Semitic articles, public officials responded by banning the sale of both the Independent and an opposing paper called Facts. The ACLU protested and asserted that “every view, no matter how ignorant or harmful we may regard it, has a legal and moral right to be heard.” In other words, the proper response to hateful speech was more speech. And the way to combat abhorrent views was by argument, not by prosecution or violence. Most remarkable is the fact that the ACLU’s position evolved in a near vacuum of legal doctrine, and at a time when there was little public tolerance for unpopular views. Indeed, for much of American history the First Amendment was an empty promise. Following the ratification of the Bill of Rights, it took nearly one hundred and thirty-five years before the Supreme Court assumed responsibility for defending free speech and association. Until then, majority rule seemed to justify the suppression of unpopular ideas and groups. And when the subject of liberty was broached at all it was in the context of economic freedom, that is, the right to engage in economic pursuits free of government restraint. THE TURNING POINT FOR THE SUPREME COURT The turning point came in 1925 when the Supreme Court accepted the principle that the Fourteenth Amendment incorporated the protections of the Bill of Rights. The case involved Benjamin Gitlow, a founder of the Communist Party, who had been convicted for distributing a pamphlet that advocated revolution but did not urge any immediate illegal action. Unfortunately for Gitlow, the Court upheld his conviction. But in a crucial passage, conservative Justice Edward Sanford held that “for the present purposes we may and do assume that freedom of speech and of the press…are among the fundamental personal rights and ‘liberties’ protected by the due process clause.” Thus the Court held out the promise of future judicial protection of civil liberties. And just two years later, in 1927, that is exactly what happened. In a case little noted at the time, the Supreme Court upheld the First Amendment rights of a union organizer. Mr. Harold Fiske thus became the first person to have his free speech right upheld by the Supreme Court. Grasping the significance, Harvard Law Professor Zachariah Chafee observed that, “In Fiske, the Supreme Court for the first time made freedom of speech mean something.” Between 1937 and 1949, the Supreme Court created the first significant body of civil liberties law in American history. President Franklin Roosevelt had appointed some of the greatest civil libertarians ever to sit on the Court, including Hugo Black, William O. Douglas, and Frank Murphy. Their impact was evident when the Court changed direction and 3 of 9 overturned the conviction of a Communist party organizer. The majority ruling held that “peaceable assembly for lawful discussion cannot be made a crime.” KOREMATSU AND THE PRESIDENT’S WAR POWERS And yet, it was this same Court that upheld Roosevelt’s Executive Order authorizing the internment of more than 110,000 individuals of Japanese ancestry. A full two-thirds of these individuals were American citizens. No charges were brought against them; no hearings were held; no one was told where they were being taken, or how long they would be gone. The ACLU challenged the internment action before the U.S. Supreme Court, but the case was lost in a six-to-three decision. Dissenting from the majority, Justice Murphy said the evacuation program went “over the brink of constitutional power and into the abyss of racism.” Justice Owen Roberts called the evacuation “a clear violation of constitutional rights.” And Justice Robert Jackson warned that the majority had set a dangerous precedent with regard to the president’s war powers. “A judicial construction of the due process clause that will sustain this order,” Jackson wrote, “is a far more subtle blow to liberty than the promulgation of the order itself.” Once validated, this principle he said “lies about like a loaded weapon ready for the hand of any authority that can bring forward a plausible claim of an urgent need.” Jackson’s warning was prophetic, as future crises invoking national security would later make clear. The wartime internment of Japanese-Americans demonstrated what happens when popular fear and prejudice are allowed to dictate policy, and even good men and women lose their faith in the Constitution and the Bill of Rights. Let’s never forget that this most shameful example of deprivation of rights was approved by three of the greatest names in American liberalism: President Franklin Roosevelt; Earl Warren, who at the time was Attorney General of California; and Supreme Court Justice Hugo Black. ACLU’S ABANDONMENT OF PRINCIPLE Even the ACLU itself fell victim to widespread fears, in this case fears of Communism and Communist sympathizers. In 1940 the board adopted a policy barring from official positions anyone who supported totalitarian movements and purged Elizabeth Gurley Flynn from its ranks. These actions legitimized the idea that Communists were not entitled to constitutional protections, an idea that became a cornerstone of the cold war. The ACLU’s abandonment of principle also obscured the courageous actions it subsequently took against loyalty oaths, the House Un-American Activities Committee, blacklisting and other anti-Communist measures. It also meant that the ACLU entered the cold war deeply divided and, therefore, weakened for the head-on assault against free speech and assembly. COLD WAR RETREAT FROM FREE SPEECH American opinion during the cold war was also deeply divided with many people questioning just how broad the scope of civil liberties should be, given the rise of totalitarian movements and the threat they posed to democracy. This fundamental question was never really resolved. Instead, many Americans put Communist-related issues into a separate category, and then forged ahead to expand the civil liberties agenda in other areas, such as civil rights, freedom from censorship, separation between church and state, and due process of law. 4 of 9 The Supreme Court similarly bifurcated Communist and non-Communist issues. The situation became aggravated in 1949 when the Court’s civil libertarian bloc was decimated by the deaths of Justices Frank Murphy and Wiley Rutledge. Given this loss, it was not surprising that the Court subsequently upheld virtually all cold war measures, even retreating from earlier decisions protecting unpopular speech. The most serious setback occurred in 1951 with the Court’s decision in Dennis v. United States, which Roger Baldwin at the time described as “the worst single blow to civil liberties in all our history.” The Court sustained the convictions of twelve top Communist party leaders and upheld the constitutionality of the Smith Act, the first peacetime sedition law in American history. More significantly, the Court’s decision in Dennis marked a retreat from the clear and present danger test. That earlier standard was replaced by a “grave and probable” standard that was far less protective of free speech. The majority’s ruling evoked a forceful dissent from Justice Hugo Black who expressed the hope that “in calmer times, when present pressures, passions and fears subside, this or some other Court will restore the First Amendment liberties to the high preferred place where they belong in a free society.” THE GREATEST DECADE This terrible defeat was followed by a decade that marked the greatest advances in civil liberties in American History. From 1954 through 1964, the Supreme Court led the attack on racial segregation, banished religious exercises from public schools, dismantled the machinery of censorship, protected freedom of association, forced legislative redistricting, and introduced constitutional standards of due process in criminal justice. These were great years for the ACLU. We played a leading role in virtually every major Court decision and, in several, directly influenced the Court’s thinking. The ACLU’s membership grew from thirty thousand in 1955 to eighty thousand in 1965. A new sense of freedom was in the air and it led to a general trend toward expanding liberties. The decade ended with the Warren Court’s resounding defense of free speech in a case that was a product of the civil rights movement. The Birmingham, Alabama police and fire commissioner had sued the New York Times for libel and won a $550,000 judgment. But on appeal, the Supreme Court overturned the judgment. The most important aspect of the decision was Justice William Brennan’s ringing affirmation of the First Amendment. “Debate on public issues,” Brennan wrote, “should be uninhibited, robust and wide-open.” Further he stated, “The constitutional protection does not turn on the truth, popularity, or social utility of the ideas and beliefs which are offered.” THE PENTAGON PAPERS Just how uninhibited, robust and wide-open the debate should be was tested on June 13, 1971, when the Sunday New York Times published the first installment of the socalled Pentagon Papers, a stolen top secret document detailing U.S. involvement in Vietnam. The White House asked the Times to stop further publication of the series, and when it refused, the Justice Department won a restraining order against the paper. It was the first time in American history that the federal government had gotten a prior restraint ruling against the 5 of 9 press. Then the Washington Post began publishing its own series, and the Justice Department immediately enjoined that paper as well. The case was appealed to the Supreme Court which, in a six-to-three vote, overruled the government and allowed the papers to continue publishing the series. It was a great victory for the First Amendment and a stinging rebuke to the Nixon administration. But as in all great victories, this one carried the seeds of the next great challenge. John Shattuck, the head of the ACLU’s Washington office was one of the first to point out the fact that the Court’s ruling suggested the president and the Congress had the inherent power to restrain the press in national security matters. The ruling, therefore, accelerated the trend toward secret government under the guise of national security. NATIONAL SECURITY AS A CIVIL LIBERTIES ISSUE National security became a civil liberties issue by introducing a new element into the exercise of free speech. Earlier, I spoke about the speaker’s right to express a different view, and the listener’s right to hear different views. National security added a third dimension and that was the public’s right to check the government’s inclination toward secrecy. The exercise of this right can only be accomplished by eliminating or substantially reducing the gap between what the government knows and what it wants the public to know. If secrecy and covert action are allowed, then the basic premise of democracy is violated, and the public cannot exercise its constitutional right of control over government policy. Secret government is the crux of the issue in the current war on terror. We see it in such actions as secret and indefinite detentions, secret immigration and deportation hearings, secret “no fly” lists, secret “sneak and peek” searches, secret surveillance of ordinary Americans, the use of secret evidence against so-called enemy combatants, and proposed use of secret evidence in military tribunals. Consider, for example, the secret deportation hearings conducted by the government as part of its investigation of the 9-11 terrorist attacks. The hearings were used against hundreds of Arab and Muslim immigrants who were rounded up and detained. Not only were the deportation hearings held in secret, the government refused to disclose even the names of the men it held or the circumstances of their arrests. The ACLU brought suit arguing that transparency and accountability are essential to the workings of democracy. While we lost one case in New Jersey, the ACLU won a precedent-setting decision in the U.S. Court of Appeals in Cincinnati. In the latter case, the court ruled against the government, declaring the secret hearings unlawful. The judge ruled that “a government operating in the shadow of secrecy stands in complete opposition to the society envisioned by the framers of our Constitution.” “Democracy,” he wrote, “dies behind closed doors.” And so it, in fact, did since almost all of the people detained were ultimately deported or removed for minor immigration violations unrelated to the terrorist attacks. The ACLU has also filed a friend-of-the-court brief in federal court challenging the government's decision to detain U.S. citizen José Padilla in a military jail. The government’s actions in this case are a breath-taking example of seizing excessive 6 of 9 powers. Mr. Padilla, an American citizen, accused of being involved in a plot to detonate a low-level radioactive bomb, was arrested on American soil, held without charge, and initially denied the right to legal counsel. A federal judge eventually ruled that Padilla had the constitutional right to consult with a lawyer and offer facts to rebut the government’s evidence. The government suffered a further setback when a federal appeals court ruled that Padilla’s detention exceeded the authority of the executive branch; that he must be either charged under the criminal justice system or released. A similar situation exists with Yaser Hamdi, an American citizen who is also under indefinite detention in a military jail. Unlike Mr. Padilla, Mr. Hamdi was captured in Afghanistan and accused of fighting for the Taliban. For several months the Pentagon refused to provide Hamdi with access to legal counsel. It then reversed its position and granted access to counsel a day before the Justice Department was required to file a brief with the Supreme Court. The reversal was done to shield the government’s actions from criticism and reversal by the Court, but not as a change in policy. Finally, in a further setback to the government, a federal appeals court ruled that terrorist suspects held in secret U.S. custody at the Guantánamo Bay Naval Base in Cuba should be allowed to see lawyers and have access to courts. The case involved a Libyan captured in Afghanistan by the U.S. military in the months after the 9/11 attacks. The judges said his continued detention "is inconsistent with fundamental tenets of American jurisprudence and raises most serious concerns under international law." Unfortunately, a DC federal appeals court had earlier ruled that it lacked jurisdiction over the Guantánamo detentions. These federal court decisions have laid the foundation for a blockbuster highcourt showdown over the extent of presidential powers in wartime. In fact, the Supreme Court next month will hear all three cases: Padilla, Hamdi and Guantánamo. The Court’s rulings will, hopefully, lead to a more constitutionally appropriate balance between security and liberty. GROWING CONSTITUENCIES OF SUPPORT I emphasize the word “hopefully” because civil liberties have come a long way since the assault on liberty during World War I. That assault marked the first time in American history that the federal government played the key role in the suppression of unpopular ideas. Prior to that point, vigilantism had been local and ad hoc. The federal government’s new role helped shift the balance away from liberty and toward a new national security state. But in the following nine decades civil liberties have successfully penetrated the fabric of daily life across the country. The ACLU has also succeeded over the years in taking the good fight into new issues and geographic areas long untouched by liberty. As a result, there are large, diverse and growing constituencies of support for civil liberty across the country and across the political spectrum. I offer as evidence the two hundred and sixty communities in thirty-seven states that have adopted local resolutions in support of the ACLU’s “Safe and Free” message. 7 of 9 These communities represent an extraordinarily diverse group of Americans—more than forty-three million people from small towns, such as North Pole, Alaska and Carrboro, North Carolina, all the way to large metropolitan areas like Los Angeles, Chicago, and New York City. The supporters of these efforts are conservatives, liberals, moderates and independents—people concerned about the impact of decisions and actions the government is taking with serious consequences for their personal freedom of expression, of association, and—most importantly—the freedom to be left alone in their individual pursuit of life, liberty and happiness. We see a similar momentum building in Congress. A growing number of Members are concerned about the dangerous expansion of government powers granted under the PATRIOT Act. There is, for example, a bipartisan group of lawmakers that supports “The Security and Freedom Ensured (SAFE) Act.” That proposed legislation is aimed at bringing provisions of the PATRIOT Act in line with the Constitution. It is supported by Senators Larry Craig, Republican from Idaho, and Richard Durban, Democrat from Illinois—two men who are rarely on the same side of an issue. In this case, however, they share a concern over protecting liberty in a time of crisis. So far the Senate has also rejected the Administration’s continued attempts to extend the expansion of powers in the PATRIOT Act beyond the year 2005, when they are set to expire. Unfortunately, President Bush has made the Act’s extension a cornerstone of his policy agenda over the next year. Strange bedfellows also exist in the House where Members have voted overwhelmingly to scale back one of the most dangerous provisions in the PATRIOT Act— the one that authorizes the FBI to obtain warrants for so-called “sneak and peek” searches. These searches apply to any and all criminal offenses and are not limited to terrorist investigations. Moreover, the individuals who are the subjects of these searches are not notified until weeks or even months later. The sponsor of the legislation that would repeal this part of the PATRIOT Act is Representative “Butch” Otter, a conservative Republican from Idaho. CONCLUSION: THE CHALLENGE AHEAD Many supporters of civil liberties feel that the challenge ahead is to prevent backsliding in areas of hard won victories. I certainly would not disagree. Roger Baldwin famously cautioned that “no victory ever stays won.” At the same time, I am convinced that we also face the challenge of educating the larger public about the positive role the Bill of Rights and the First Amendment, in particular, have played in American history. We also need to do a better job of communicating the fact that tolerance, fairness and equality are the direct results of defending unpopular ideas and groups. The Constitution and the Bill of Rights are the real sources of our strength as a people and as a nation. We should never give up or compromise what is essentially our most important advantage, one that fundamentally distinguishes us from the enemy. Remember, even when democracies fight with one hand tied behind their back, they still have the upper hand. 8 of 9 Thank you. 9 of 9