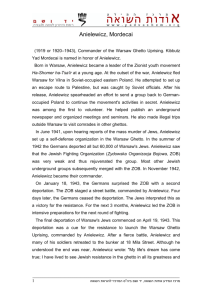

chapter e - jewish resistance

advertisement