Hamlet Reading Schedule and Journal 2013.doc

advertisement

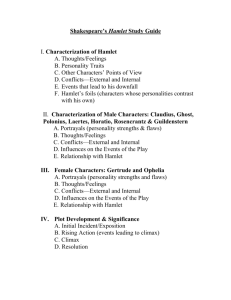

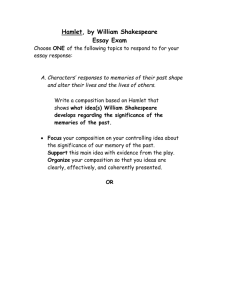

Hamlet/Shakespeare Reading Schedule and Journal Reading Schedule The near future will be focused largely on the play Hamlet by William Shakespeare. We will be reading at home and in class. Our reading for the next night will depend on what we accomplish in class. We will also be watching clips from multiple versions of the film. Simultaneously, we will be watching excerpts from Waking Life. We will be discussing the philosophical concepts presented within Waking Life in relation to Hamlet. As You Read: - Keeping in mind the essential questions of this unit, you should keep sticky notes of the reading. Bring these sticky notes to class, along with a pack of unused sticky notes. You should have at least three sticky notes per act (more for the longer acts). The reading quizzes (details below) will depend on you having these sticky notes. On these sticky notes, please mark significant quotations representative of characters searching for meaning, struggling on how to live their lives, or questioning reality. Briefly explain each quotation’s significance on the sticky note. Doubtful on how you can accomplish this? Here are some topics that have to do with above: o revenge o decay and corruption o appearance vs. reality o duty (as son, ruler) and morality o sanity vs. insanity o purpose of life I will periodically be checking with you to check in on how you are doing with the sticky notes. After Reading: - After reading, please also PRINT 4-5 COPIES of an important passage in the reading to analyze with your group. This passage may either relate to the themes above, an ulterior theme, or be important to characterization, plot, mood, or setting. - Come up with at least three open-ended questions that will inspire discussion among your group. These will probably occur to you as you read. You may mark these on sticky notes if you like. Formatives: 2 reading check quizzes Daily participation in group readings and discussion Close Reading Analysis on 2 Soliloquies (minimum) Summative: Hamlet and Waking Life Talk Show Project (details TBA) 20 points 25 points 30 points Hamlet, the first in Shakespeare's series of great tragedies, was initially classified as a problem play when the term became fashionable in the nineteenth century. Like Shakespeare's other problem plays -All's Well that End's Well, Troilus and Cressida and Measure for Measure -- Hamlet focuses on the complications arising from love, death, and betrayal, without offering the audience a decisive and positive resolution to these complications. This is due in part to the simple fact that for Hamlet, there can be no definitive answers to life's most daunting questions. Indeed, Hamlet's world is one of perpetual ambiguity. Hamlet can be sub-categorized as a revenge play, the genre popular in the Elizabethan and Jacobean periods. Elements common to all revenge tragedy include: 1) a hero who must avenge an evil deed, often encouraged by the apparition of a close friend or relative; 2) scenes of death and mutilation; 3) insanity or feigned insanity; 4) sub-plays; and 5) the violent death of the hero. Seneca, the Roman poet and philosopher, is accepted to be the father of such revenge tragedy, and a tremendous influence on Shakespeare. Thomas Kyd's Spanish Tragedy, written in 1592, is credited with reviving the Senecan revenge drama as well as spawning many other plays, such as Marlowe's The Jew of Malta, Webster's The Duchess of Malfi, the Ur-Hamlet (see the sources section), and Shakespeare's own Titus Andronicus, in addition to Hamlet.