Report template long - NatCen Social Research

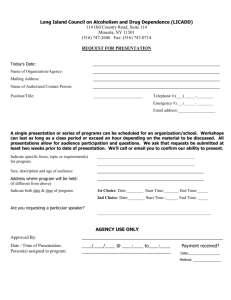

advertisement