AdvanceOrganizers.doc

Theory: Advance Organizers

Theorist: David P. Ausubel

Biography

David Paul Ausubel was born on October 25, 1918 in Brooklyn, New York. He earned an

A.B. degree from the University of Pennsylvania in 1939 and the M.D. degree from Middlesex

University in 1943. In 1950, Ausubel received his Ph.D. degree from Columbia University.

Ausubel served on the faculty of the University of Illinois from 1950 to 1955 and the University of Toronto from 1966 to 1968. From 1973 to 1975 he was head of the Ph.D. program in educational psychology at the City University of New York. After his retirement from academia, he worked as a psychiatrist at the Rockland Children’s Psychiatric Center (Ohles, Ohles, &

Ramsay, 1997). He authored numerous books and textbooks in the area of educational psychology and child and adolescent development. Ausubel developed a theory of meaningful reception of learning to explain how students use cognitive structures and processes to interpret their environment to produce meaning; much of his research centered on the study of expository teaching and reception learning, which he considered to be the primary modes of education used in the classroom (Driscoll, 2000). He died in Hyde Park, New York on July 9, 2008 at the age of

89 years (“Death Notice Ausubel,” 2008).

Description of Theory

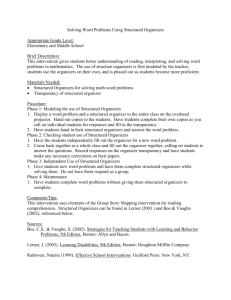

Advance organizers are introductory instructional materials that are presented to the student prior to presentation of a primary learning unit. Basically, the mission of the advanced organizer is to help integrate new information into the student’s existing cognitive structures; they do this by facilitating the introduction of new information into the existing

cognitive structures and by helping the learner to discriminate between new ideas and existing ideas that might be similar in concept. Advance organizers serve to connect what the learner already knows with what he needs to know before he can learn the new material in a meaningful way. They provide anchoring points in the learner’s cognitive structure to which the new information can be subsumed or attached and serve as a type of scaffold that will help the learner incorporate and retain the new information that will be presented in the subsequent learning unit

(Ausubel, Novak, & Hanesian, 1978).

Advance organizers are based on a learning assimilation theory developed by Ausubel, which explains the cognitive processes and associated structures for learning new information.

According to assimilation theory, new information is linked into existing ideas contained in hierarchical cognitive structures. The ideas that are higher in the hierarchy are more inclusive and easier to remember, whereas the ideas that are lower in the hierarchy are more specific and difficult to remember. When new information is linked, the existing structure and new information are changed in a process that Ausubel called meaningful learning. Assimilation theory states that there are three major types of meaningful learning: subordinate learning, superordinate learning, and combinatorial learning. The classification of these types is based on where in the hierarchical cognitive structure the new information is placed. Subordinate learning has two variants, derivative subsumption and correlative subsumption. In derivative subsumption, new information is linked as a subordinate idea to an existing parent (or subsuming) idea in the structure; the essential nature of the parent idea is not changed, but the new information is viewed as another case or extension of the existing idea. In correlative subsumption, a new idea is also linked to the superordinate existing idea, but the addition changes the existing idea in some manner. This process of correlative subsumption is termed

progressive differentiation. In superordinate learning, the new idea is a more inclusive idea than a set of existing idea so it subsumes the existing ideas and becomes a superordinate node in the cognitive structure hierarchy. Finally, in combinatorial learning, the new idea is related to existing ideas but it is neither more specific nor inclusive than the existing ideas; the new idea can be said to generally relevant to the existing new ideas. The processes of superordinate and combinatorial learning are termed integrative reconciliation and involves the recombination of existing ideas with the new (Ausubel, et al., 1978).

Cognitive structures vary widely between students, so advance organizers must be designed to work for a heterogeneous population. To accomplish this design objective, Ausubel et al. (1978) emphasized that “organizers are presented at a hgher level of abstraction, generality, and inclusiveness that the new material to be learned” (p. 172). Driscoll (2000) expanded on this point by explaining that while it might be desirable to have an advance organize tailored for every learner, this is not a realistic expectation. To meet the needs of all learners, therefore, the organizer needs to be general enough to fit into a variety of existing cognitive structures. The inclusive nature of organizer allows its ideas to serve as an anchor from which the less inclusive, detailed material presented in the learning unit can be susbsumed; the advance organizer serves to prepare a cognitive structure for use with the subsequent learning unit.

Ausubel (1978) explained that different types of advance organizers are used for different types of information. If the material to be learned is mostly new, then an expository organizer should be used. An expository organizer will help create subsumers in the learner’s cognitive structure that relate to the existing ideas in the cognitive structure and to the new ideas that are to be presented in the learning unit. If the material to be learned is mostly familiar, then a comparative organizer is used. Like the expository organizer, the comparative organizer provides

scaffolding for the new ideas to be introduced. In addition, the comparative organizer serves to

“increase discriminability between the new ideas and the previously learned ideas by pointing out explicitly the principal similarities and differences between them” (p. 253). Comparative organizers, therefore, provide for both the facilitation of the introduction new ideas as well as the minimization of potential interference coming from familiar but new ideas.

Advance organizers are often confused with overview or summaries. The critical difference between the an advance organizer and an overview is that an overview is generally written at the same level of abstraction, generality, and inclusiveness as the learning materials, so they lack the ability to bridge the gaps between what the user knows and the learning materials.

Overviews attempt to achieve their results through such means as repetitions, summarization, emphasis on key facts, and familiarization with keywords. Summaries are presented after the learning material, so they cannot provide the preparatory assistance of the advance organizer

(Ausubel et al., 1978).

It is important the advance organizers be prepared for each new unit. Organizers need to be designed to provide anchoring points that are specific to the new material to be introduced.

Existing subsumers in the learner’s cognitive structure may not be relevant to the new material and would not provide a good anchor point. After learning the material, it is possible that a learner might construct a subsumer that would be adequate for similar future learning, but it is more likely that a more suitable subsumer would be constructed through an advance organizer designed by an instructor or instructional designer who is a subject matter and pedagogical expert (Ausubel et al., 1978).

Ausubel et al. (1978) noted that the effectiveness of an advance organizer is somewhat dependent on the organization quality of the new learning unit. If the learning unit is well organized, progressing from more-inclusive to less-inclusive, than the effect of the organizer is likely to be less than it is for poorly designed learning units. Factual material is likely to be more suitable to be used with advance organizers that abstract materials since, by their very nature, abstractions “contain their own built in organizers – both for themselves and for related detailed items” (p. 172).

Measurement

A number of studies and experiments have been conducted to measure the effectiveness of advance organizers in learning and retention. A typical study was described by Ausubel

(1960) which tested the use of an advance organizer for a learning unit dealing with the metallurgy of carbon steel. To establish equivalency between the experimental and control groups in terms of their ability to learn difficult scientific material, the subjects were first given a reading passage concerning the endocrinology of human pubescence and then tested with a multiple choice exam. Subjects were then matched according to their test results and place in experimental and control groups. Experimental and control groups were then given advance organizers to read. The experimental group received an advance organizer on alloys and metals that was prepared in accordance with the principles of having a higher level of abstraction, generality, and inclusiveness than the learning unit. The control group was given an advance organizer that consisted of historical background on steel and iron processing methods; this type of material was typical of textbook introductions and did not posses the recommended attributes of advance organizers. After using the advance organizers, both groups studied the learning unit dealing with the metallurgy of carbon steel and took a multiple choice test on the steel learning

unit three days later. Test results between the two groups were used to form a conclusion about the effectiveness of advance organizers. A later study performed by Ausubel and Fitzgerald

(1961), which was based on a learning unit about Buddhism, introduced an additional special control group. The special control group used an advance organizer whose subject was endocrinology, and did not complete the learning unit on Buddhism prior to taking the test. The purpose of this special control group was to “ascertain to what extent mere knowledge of the comparative organizer (without any exposure to the Buddhism learning package itself) could increase scores on the Buddhism test beyond chance expectancy” (p. 269). In a paper that addressed the results of several critical studies on advance organizers, Ausubel (1978) urged researchers to more fully understand the concepts of advance organizers before criticizing them and to consult the primary sources for details on research methodologies of prior studies, such as the use of the special control group.

Prepared By: Jon Martens

References

Ausubel, D. P. (1960). The use of advance organizers in the learning and retention of meaningful verbal material. Journal of Educational Psychology, 51 (5), 267-272.

Ausubel, D. P. (1978). In defense of advance organizers: a reply to the critics. Review of

Educational Research, 48 (2), 251-257.

Ausubel, D. P., & Fitzgerald, D. (1961). The role of discriminability in meaningful verbal learning and recognition. Journal of Educational Psychology, 52 (5), 266-274.

Ausubel, D. P., Novak, J. D., & Hanesian, H. (1978). Educational psychology: A cognitive view

(2nd ed.). New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston.

Death Notice: Ausubel, David P. (2008, August 10). The New York Times , p. A.34.

Driscoll, M. P. (2000). Psychology of learning for instruction (2nd ed.). Boston: Allyn and

Bacon.

Ohles, F., Ohles, S. M., & Ramsay, J. G. (Eds.). (1997). Biographical dictionary of modern

American educators . Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group.