Value-creating Systems

advertisement

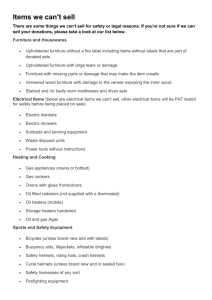

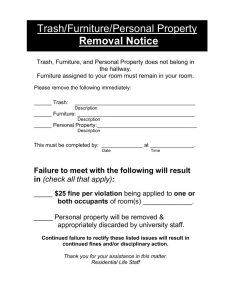

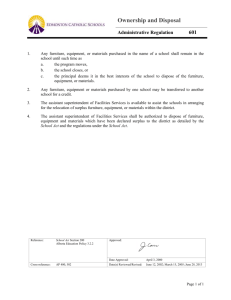

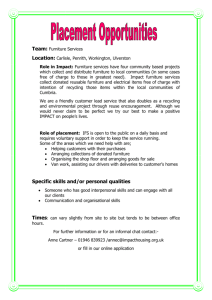

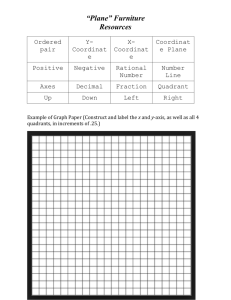

Strategic Management Conference 1996 The Value Net: A Methodology for the Analysis of Value-Creating Systems Cinzia Parolini Most recent studies in strategic management underline the emergence of related paradigm shifts in technology, corporations and industries. As a matter of fact, nowadays it is difficult to run across an article in a business magazine academic or review which does not take into careful consideration the impact of technology on competition, the increasing innovation rate, the blurring of industries' boundaries and the continuous shifting and increasing permeability of firms' borders. Even if most of these contributions are illuminating in so far as they point out new key issues in strategic management, new and clear operative models and tools coherent with the new competitive landscape have failed, as yet, to emerge. The use of such terms as “boundaryless organization”, “virtual corporation”, “extended enterprise”, “blurring industry boundaries” is now widespread, but when business analysts have to do their work, they find within their strategic tool box essentially the same models conceived in the 70s and 80s and by and large still in use, such as “portfolio matrices”, “Porter’s five forces model”, and “the value chain”. One possible explanation for this lack of innovation in strategic models and tools can be found in the human reluctance to reconsider concepts so rooted in traditional economic theory as to be considered immovable. Disturbing though it may be, we must admit that the starting point for the development of a new set of strategic tools can only emerge from a radical change in some of the most basic concepts upon which economic theory itself has been built. Consolidated concepts such as "firm" and "industry" must be reconsidered. We must rethink and redefine the traditional concepts of "firm" and "industry", and overcome mental images and schemes which are so widely accepted as to appear “beyond question” even if they no longer reflect reality. Painful and risky as this may be, if reality is experiencing a paradigm shift, our mental paradigms must shift as well. FROM THE FIRM TO VALUE-CREATING SYSTEMS AS THE STRATEGIC FOCUS In order to understand how to modify our concept of "firm", we have to imagine what the "new corporation" will look like in the year 2000 and beyond. The transition toward a new technological and economic paradigm is still on the way, and therefore it is difficult to describe emerging models precisely. We can only draw an outline based on the characteristics of those companies which, more than others, seem to fit the new environment. The profile of the new corporation is that of an organization with a strong hold on its core competencies, which is able to exploit them on a variety of markets. It is an organization well integrated in a network of alliances and long term relationships and therefore able to leverage its own resources and take advantage of external ones. From the organizational point of view, the new corporation presents a lean and compact internal organization on the one hand and flexibility with respect to its boundaries and external connections on the other. The continuous shifting in firms' boundaries and the presence of flexible but strong connections with other economic actors together lead to sets of economic actors (mainly firms, but also final customers, public entities, non-profit organizations) which, though separate from a juridical point of view, and carrying on relatively autonomous strategies, act as elements of the same integrated body. One of the most interesting aspects of the model we have sketched above is that firms coming from completely different backgrounds seem to converge towards this kind of configuration. This lean, integrated, flexible and interconnected model seems to attract large integrated companies as well as small ones and this confirms the hypothesis that it is the outcome of an emerging environmental paradigm. In the last few years many large companies have gone through split offs, the outsourcing of non-core processes, the dismissal of non-core products and so on. In successful reorganizations, the result has been lean, more agile companies interconnected in a web of relations with external partners which carry out activities formerly performed within the company itself. On the other hand, this same interconnected model seems to attract many small and medium size companies. By creating strategic networks and establishing relations with long term partners, many small and medium size companies have found a viable way to compete in global markets and to reach the production level necessary for cost reduction of the activities performed. If the outline we have depicted is true, then we need to reconsider the use of the individual firm as the focus point of strategic analysis. If firms are increasingly inserted in a system of strong relations with other economic actors and if competition takes place not only among companies but also and mainly among networks of partners co-producing value for and, sometimes, with final customers, then we should start conceiving of strategies at a higher level: the value-creating system level. In addition, we will need a new set of strategic tools coherent with our new strategic focus. First, what do we exactly mean by a value-creating system? To use an example from a well-known competitive system, let us consider how the value connected to a personal computer is created with reference to the professional user segment. PC professional users can receive value thanks to the coordinated implementation of a variety of activities such as microprocessor production, personal computer assembling, software development, hardware and software distribution, telecommunication services production, Internet access provision and so on. These activities are carried on by different economic actors, each one influencing the value that others can deliver. This is true for actors linked in a sequential way (for example the microprocessor determines the power of the personal computer and, therefore, the value that a personal computer producer can deliver to customers). It is 2 also true for non-sequential activities (for example the value that a software house can deliver may be limited by the unavailability of microprocessors powerful enough). In value-creation, distribution activities can be as important as production activities in determining the global satisfaction of final customers. If, after having waited two months, we receive a PC which is configured differently from how we had asked, as customers we are dissatisfied. Maybe the computer shop made a mistake in forwarding the order to the PC assembler. Maybe the PC assembler did not understand the shop order. Maybe the microprocessor producer was late in delivering critical components. We don't know and probably we don't care: we only know that the valuecreating system as a whole was not able to meet our demands. And we probably blame the entire system and develop quite a poor opinion of every company involved. In PC value-creating processes, moreover, final customers not only receive and consume the value created: they also participate in value-creating activities, such as hardware and software installation, customized software development and so on. The value final customers receive, lastly, is also influenced by their ability to exploit the potentialities of hardware, software and telecommunications. The value-creating system concept emerges quite easily from the aforementioned simple example . By "value-creating system" we mean a set of interlinked activities that create value for final customers. In order to leverage at best their resources and competencies, firms should not limit their perspective to their value chain (set of sequential activities) or, even worse, to their direct suppliers and customers. In conceiving of their strategy, they must take into account the whole value-creating system within which they operate, and, if possible, assume the point of view of the final customer. In order to avoid misunderstandings, it may be useful to emphasize that by claiming that strategic decision makers should focus on value-creating systems, we do not mean that a single company should try to control directly most of the critical activities within the system. We simply claim that in order to maximize customer value, companies should also take into account activities performed by others (customers included), thus assuming a “system perspective”. The concept of a “value-creating system” is not new in strategic management literature. According to Normann and Ramírez (1993), "in so volatile a competitive environment, strategy is no longer a matter of positioning a fixed set of activities along a value chain. Increasingly, successful companies do not just add value, they reinvent it. Their focus of strategic analysis is not the company or even the industry but the value-creating system itself, within which different economic actors - suppliers, business partners, allies, customers - work together to co-produce value". Porter (1985), although adopting a different perspective, underlines that "a firm's value chain is embedded in a larger stream of activities that I term the value system (...). Suppliers have value chains (upstream value) that create and deliver the purchased inputs used in a firm's chain. (...) In addition, many products pass through the value chain of the channels (channel value) on their way to the buyer". Although Normann and Ramírez propose to overcome the sequential approach of the value chain model, all these authors underline how the value received by the customer is the outcome of a set of activities carried on by a number of actors. A relevant difference between these authors is that whereas Porter assumes the firm's value chain as the starting point of 3 strategic analysis, Normann and Ramírez stress the importance of assuming the valuecreating system itself and not the firm as strategic focus. FROM THE “FIRM” TO ACTIVITIES AS ELEMENTARY UNITS OF ANALYSIS The author not only accepts value-creating systems as the focus of strategic analysis, but also proposes to go one step further and to consider value-creating systems as a set of activities, not as a set of economic actors. This means defining activities as elementary analysis units, leaving aside (at least in the first phases of the analysis) how activities are divided among the economic actors involved. This choice is the basis of the development of truly flexible strategic tools, as it leads to a strategic analysis where first of all activities creating value for final customers are identified and their structural analysis is made. Only after this first phase can the analysis go on to consider who (in a given time and place) does what. In an economic environment where firms' boundaries shift continuously and, in addition, borders are relatively less important because of their high permeability to any kind of flow (principally flows of information), this choice enables the analyst to focus his/her attention on how value is created, regardless of the firms' ever changing make/buy/connect choices. This does not mean that make/buy/connect choices are not crucial to companies' success. On the contrary, an in depth analysis of how value is created (or can be created) and of the structural characteristics of the activities to be performed is the basis of all truly strategic make/buy/connect decisions. Using the PC example, figures 1 and 2 show in graphic form the differences between the “value chain” approach and the approach presented in this paper, an approach that from now on I will call the "value net” approach. Producers of components PC assemblers Computer shops PC users Figure 1: The “value chain” approach 4 Management of Data Banks Components’ production Hardware assembly Telecommunication services Retailing Software production PC Use Assistance Figure 2: The “value net” approach VALUE-CREATING SYSTEMS: DEFINITION AND BOUNDARIES If we are to accept the new focus the strategic analysis upon value-creating systems, it is essential to provide a clear definition of the concept. This is crucial because the value-creating system is to the value net approach what the firm was to traditional strategic models. A universally accepted definition of value-creating systems still does not exist, as the idea of substituting this concept for the concept of “firm” (or at least adding to it) within strategy formulation processes is very recent. Value-creating systems can be described as follows: a value creating system can be defined as a set of activities creating value for the customers; value-creating systems include both creation and consumption activities satisfying specific needs; the definition of value-creating systems' boundaries is guided by the consumption activity of final customers; activities are performed using sets of tangible, intangible and human resources; activities are linked by flows of materials, information, financial resources; these resources can be controlled and managed by different organizations (firms, customers, public entities, non-profit organizations) that perform one or more activities within the system; final customers not only receive and consume the value created, but also participate in value-creating activities; the value final customers enjoy is also a function of the way they use and "consume" the potential value received; 5 activities (and related resources) can be coordinated by market, hierarchy or hybrid mechanisms (networks); a single firm can participate in more than one value-creating system. Linking value to value-creating systems as opposed to single firms means that we must assume the final customers point of view, and try to find out where the value they receive comes from. As underlined above, the amount of value they can enjoy depends on the performance (more or less coordinated) of every actor participating in the system and, sometimes, also on the customers' ability to take advantage of the offer. A white collar worker using a PC, for example, could use his or her PC at one tenth of its potential because of his or her lack of training on the software used. And this lack could be the result of the fact that the company that bought the software did not want to pay for the users' training. Or it could also depend on the fact that the software house developed a product which does everything but is very difficult to use. In other words, the customers not only are the receivers of value, but also play an active role in value creating processes, together with other actors involved. Although focusing on value-creating systems makes it easier to understand the sources of value for customers, from the practical point of view this approach can raise some doubts. Could it be that the adoption of the value-creating system concept leads to sets of activities too large to be meaningful? Is there a risk that such a wide perspective could make companies lose time analyzing activities they cannot control? As a matter of fact, the risks outlined above do exist. If taken to its extremes, the value-creating system concept would lead to sets of activities too large to be analyzed. Moreover it is highly probable that the company that carries on the analysis could play a significant role only within a limited sub-set of the system. Whereas firms' boundaries, even if highly permeable, can be drawn with certainty, value-systems' borders cannot be defined objectively. This means that the analyst has to use his or her sensibility and experience in order to draw subjective boundaries around a given value-creating system. Let us make an example. When we sit in front of our computer to consult a CD ROM containing the articles published over the last ten years by an international business magazine, we enjoy the value created by hundreds of activities: article writing, photograph making, text and image digitalizing, CD ROM production, research and production of hardware components and of the PC itself, development of the software used for the search and so on. And we could go on with the list, mentioning the production of cathodic tubes contained in the screen, the development of the wordprocessor used by journalists, the telecommunication services journalists used to transmit their articles and so on. Thousands of people and hundreds of companies have made it possible for us to search easily through thousands of articles saved on a single CD ROM. Fascinating though it may be, when we have to carry on a strategic analysis this perspective is much too wide from a practical point of view. If it is true that value creating systems have no objective boundaries, it is also true that strategic analysts have to decide how far they must go in the analysis, where to cut off connections, which activities to study in depth and which ones to consider at a synthetic level. In other words, it is useful to have a comprehensive framework, but within that 6 framework the magnifying glass has to be used only on the sub-set of activities that are relevant to the company carrying out the analysis or that could be crucial in the future. The aforementioned remarks also imply that sometimes the analysis should be stopped before arriving at final customers. If, for example, we are studying the machine tool industry, extending the analysis to consider the consumption of cars may be excessive: in this case the boundary could be drawn soon after the automobile producers. THE VALUE NET: A TOOL FOR THE ANALYSIS OF VALUE-CREATING SYSTEMS By choosing to focus on value-creating systems as sets of activities we lay the basis for the development of a new set of strategic tools. This choice enables the strategic analyst to reconsider traditional models using a new pair of lenses; it allows him/her to separate those concepts that still make sense from the ones that were specific to the seventies and eighties and no longer fit with the new economy. The "value net" methodology has been built upon this new perspective. The value net model can be described as a tool for the analysis of value-creating systems aimed at allowing the following to emerge as clearly as possible: the entire value-creating system in which economic actors operate (the perspective is expanded to include all those value chains co-producing value for the customers); make/buy/connect choices that economic actors have made or can make within the value creating system; those activities whose control implies high profitability; those activities that don't add value proportionate to their costs or, even, those activities that subtract value; bottlenecks within the system; opportunities to reconfigure the final customers' role (for example increasing their involvement into the value-creating process); opportunities to reconfigure the value-creating system. The value net methodology proposes the use of nodes linked by arcs. Nodes represent sets of activities and related resources which are best considered together from the point of view of strategic analysis. Arcs describe relations between nodes and can represent flows of goods, information, or financial resources, depending on which aspect the analyst seeks to develop. To envision a value-creating system as a set of nodes and connected relations, rather than as a set of firms' value chains, enhances strategic creativity, as this approach helps to avoid the risk of looking at organizational and institutional boundaries characterizing a given moment in time as beyond question. Moreover, the value net approach makes it easier to compare the strategic choices made by competing economic actors by clearly distinguishing between differences in firms' boundaries (within similar value-creating systems) and differences in the configuration of value-creating systems. 7 ACTIVITY CLASSIFICATION AND NODES IN THE VALUE NET MODEL In the value net approach, nodes represent sets of activities. From a theoretical point of view, every value-creating system can be divided into an unlimited number of nodes, as immeasurable as the number of activities required to create even the most simple product. On the other hand, within any strategic analysis, activities can and have to be grouped in relatively homogeneous classes, putting together activities which are strictly linked and/or which present the same nature and cost structure. In other words, those activities which, from a strategic point of view, can be considered jointly should be grouped in a single node. Like the definition of value-creating systems' boundaries, the choice of the degree of aggregation of activities in nodes is a subjective exercise, depending also on the company which is carrying out analysis. Activities which are not considered crucial in value creation as well as those which are far from the sub-set of activities the company itself controls, can be analyzed at an higher level of aggregation. On the contrary, activities crucial in the value creating process and those directly or indirectly controlled by the company (or which the company would like to control), should be represented in more detail. In general, activities should be: disaggregated enough to highlight all the make/buy/connect options available to economic actors in the system; aggregated enough not to make the picture too complex from a practical point of view. With reference to that portion of the of value-creating system which the analyst wants to study in depth, the following operating suggestions should be taken into consideration: activities performed by different actors in value-creating system being analyzed (or in other competing value-creating systems) should be disaggregated; activities producing outputs (that is components, goods, services) that have their own market should be disaggregated; activities that differ from a structural point of view (that is, those activities having different cost structure, capital requirements, specific know how and so on) should be disaggregated; activities different in nature should be disaggregated; when the points above do not hold, activities should be aggregated. As far as the "nature" of activities is concerned, the value-creating system perspective naturally leads to an innovative way of classifying the activities themselves, partially overcoming the traditional distinctions between direct and indirect activities on one hand and between primary and support activities on the other. The necessity to innovate very consolidated and widely accepted classifications stems from the different perspective assumed by the value net approach. If the object of the analysis is the firm, then the traditional classifications will still hold. If the object of the analysis is the value-creating system, then a new classification must be conceived. From the a value-creating system perspective, all, activities fall into 3 main categories: activities regarding realization of goods and services sold; 8 activities which support other activities; activities connected to the management of external transactions. The classification outlined above is detailed in figure 3. From here on, most examples presented will be drawn from the furniture industry, as later on this industry will be used to illustrate the practical results obtainable with the value net methodology. MANAGEMENT OF EXTERNAL TRANSACTIONS ACTIVITIES SUPPORT: • to the system • to individual companies • to individual activities REALIZATION • Purchases (in a strict sense) • Sales (in a strict sense) • New product development • New process development • I.S. management and development • Data Base management and development • Human resource management • Procurement policies definition • Marketing • Infrastructural activities •Operations •Quality control •Transportation (transfer in space) •Warehousing (transfer in time) •Pre-sale customer services •Additional services •Post-sale assistance and services Figure 3: Activity classification in the value net approach. Realization activities. Realization activities are related to the physical production of goods and services to be sold and to the transfer of goods in time (warehousing) and space (transportation). This group also includes activities such as pre-sale (for example interior design services offered by furniture shops) and post-sale assistance and services (for example installation, repairs and maintenance of furniture sold), quality control, production of additional goods and services. Realization activities contribute in a physical way to the supply of a certain good or service, in a given time and place. The activities in this group are therefore linked to one another by flows of goods or services and not only by flows of information and financial resources. From the point of view of the cost structure of the economic actors involved, realization activities can imply both direct (materials, direct labor, transportation) and indirect costs and expenses (indirect labor, depreciation, fixed production and distribution costs). Support activities. Support activities make other activities possible, without intervening in the physical production of goods and services. This group includes activities such as product and process development, human resource management, information system development and management, definition of procurement and marketing policies, marketing, infrastructural activities (that is accounting, planning, finance, legal and government affairs, general management) and so on. The most important difference between realization and support activities is the fact that 9 realization activities have to be repeated for each unit sold, whereas support activities are not directly linked to volumes produced and sold. Even if support activities do not participate directly in the physical realization of goods and services, they do represent a fundamental premise for realization activities and contribute significantly to value creation through increases in value perceived by the customers, decreases in realization costs, or both. Product development, for example, has a direct impact on product functionality and on its production cost. Advertising and marketing activities can improve brand awareness and the image of products sold. Employee training may result in an increase in realization activity efficiency, whereas the development of improved production or administrative processes could reduce direct and variable costs. A relevant trend and important feature of the new economic environment is the shift from realization activities to support activities. In advanced economies, companies (as well as value-creating systems) increasingly compete at the level of their ability to build efficient and effective delivery systems, whereas the performance of realization activities loses importance. In the furniture industry, for example, handmade interior designing is slowly being partially substituted by computer aided design which helps interior designers do their work with pre-inserted component libraries and design tools. These devices enable architects working for computer shops to produce interior design projects much more easily and quickly, drastically reducing in the number of errors that can be made. This kind of tool is also the premise for the establishment of electronic connections between furniture shops and furniture producers and thus for a radical reduction of lead time at the value-creating system level. The shift from realization to support activities implies substantial changes in the cost structure of value-creating systems (and of companies contained therein) as well as major modifications in the rules of the competitive game. Usually, the growing relevance of support activities entails a reduction of direct and variable costs (that is costs that have to be sustained in proportion to quantities sold). These savings are counterbalanced by an increase in indirect and fixed costs and, within these, an increase in discretionary costs (that is costs that are not linked to production capacity but to the development of companies' potential and intangible assets). This category includes costs such as R&D , human resource development, new process development and process reengineering, advertising and costs related to brand establishment and consolidation. Besides having an impact on cost structure and, as a consequence, on economies of scale, the shift from realization to support activities also implies major changes in other elements which characterize the activities' structure, such as capital requirement, differentiation of activity outputs, switching costs and so on; these changes directly effect how companies compete on the market. For example, the introduction of computer aided interior design systems implies both a decrease in furniture shops' direct costs and a substantial increase of capital requirement and fixed costs at the furniture producers level. As a matter of fact, furniture producers must not only develop software suitable to the kind of furniture they sell, they must also convince shop directors to adopt it (sometimes giving them the software and even the hardware at a very low cost or even free of charge), to train interior designers to use it, to 10 continuously update the libraries of furniture components and so on. On the other hand, the advantages of such an approach from the furniture producers’ point of view are clear: increase in shops' switching costs, lead time and error reduction at the valuecreating system level, opportunity to differentiate their own offering in relation to competitors. From the value-creating systems perspective, support activities can be grouped into three categories: activities which support individual nodes within the system; activities which support nodes carried on by individual companies within the system; activities which support the entire value-creating system. This classification is illustrated by figure 4. Support at system level Support at company level Support to individual nodes Realization activities Figure 4 - The classification of support activities Support activities at the node level present a limited scope and support individual activities, often of the realization type. In the production of upholstered furniture, for example, leather cutting makes use of metal forms which differ according to the model of armchair or sofa produced. The production of the metal forms is one example of a support activity at the individual node level. Activities supporting individual nodes need not necessarily be performed by the same company performing the supported activity. In the shoe industry, for example, the production of metal forms is usually performed directly by the shoe producers, whereas cutting is often outsourced to external small workshops. In this case, it is also interesting to underline how the control of the support activity enables shoe producers to control the quality level of the realization activity outsourced. 11 Most support activities are not aimed at supporting individual nodes, but at sustaining more than one node. Let us take, for example, marketing activities. This kind of activity presents several relations with a number of nodes: market analysis supports new product development, advertising and promotion campaigns support sales, marketing mix choices influence distribution, pricing and so on. The same can be said for information system management, a kind of activity that, by definition, is designed to support, possibly in an integrated way, sets of interlinked activities. Activities supporting more than one node can be performed at both the company and the system level. This depends not only on the kind of activity but also and mainly on the kind of strategies carried on within the value-creating system. Activities such as financing, accounting, and legal affairs are typically performed at the company level. With some exceptions, human resource development is also usually performed to support an individual company, and therefore at the company level. Activities such as marketing, definition of procurement policies, information system management, and new product and process development, on the other hand, can be performed both at the company and at the system level. As far as this point is concerned, the increasing importance of support activities at the system level must be emphasized. In the past, the rule was that each company provided for the support of its own realization activities, developing its own products and processes, conceiving its own information systems, defining its own marketing policy and so on. One of the key features of the new economy is the increasing number of companies which have chosen to outsource realization activities and to focus on support activities, performing them at the value-creating system level. One of the most famous examples of this kind of strategy is Benetton. The main difference between Benetton and the traditional knitwear producers is the fact that Benetton has conceived of a strategy at the value-creating system level, outsourcing most of the production activities to a wide network of subcontractors on one hand and controlling the distribution through a wide network of franchisees on the other one. Benetton develops the products, defines the marketing and procurement policies for the entire valuecreating system and controls that the workload is evenly distributed among subcontractors. In order to support the entire system and speed up critical processes (such as product development, order gathering, mid-season re-orders, deliveries and so on) Benetton has also created an interenterprise information system that links it to subcontractors, agents and franchisees, contributing significantly to the reduction of lead time and time to market. The aforementioned example shows the fundamental limitation of a firm centered perspective, which considers all support activities at the same level. By clearly distinguishing between support at the company and at the system level, the value net perspective makes the description of many emerging economic models (such as, for example, lean organizations, virtual companies and strategic outsourcing) less difficult and more meaningful than would otherwise be using traditional tools. Management of external transactions. Activities related to the management of external transactions must be performed whenever more than one economic actor participates in the value-creating system. Sale and purchase activities and such sub- 12 activities as order gathering, contracting with customers and suppliers within predefined marketing and procurement policies, the assurance that agreements are respected, pressing for orders, delivery and payment, payment management and so on, essentially fall into this group. It is important that these activities not be confused with marketing or the definition of procurement policies, as these fall under the heading of support activities. In the opening paragraphs of this paper, the advantages of describing valuecreating systems without necessarily considering, at least in the first phase of the analysis, who does what, has been emphasized. This perspective implies that at the first stages of analysis it is impossible to map out all the activities related to the management of external transactions, as we are still not aware of where the borders among economic actors exactly lie. While mapping out value-creating systems as a whole, activities related to external transactions can therefore be omitted. These same activities have to be re-inserted into the picture when the analysis moves from the value-creating system to the company level, as illustrated in figure 5. S = Sale P = Purchase ABC Corp. borders S P S S P S P P P S Figure 5 - Activities related to management of external transactions. It is interesting to point out the fact that activities related to the management of external transactions are not essential to value creation, but exist only because of economic specialization. It is possible to produce goods for ones own consumption and, therefore, to create and consume value without any external transaction. This leads to the conclusion that this category of activities does not create value in a strict 13 sense, and can be regarded as the price we must pay for economic specialization and all those advantages connected to it. By claiming that activities related to the management of external transactions do not create value in a strict sense, one does not necessarily minimize the importance of those activities. To this extent it is therefore worth underlining that: the management of external transactions does not coincide with those activities performed by sale and purchase personnel, as the latter also carry on such important support activities as marketing, information gathering, procurement policy definition and so on; activities related to the management of external transactions do not create value directly but play a very relevant role in its distribution. A well-trained selling force, for example, is crucial in order to boost sales and to obtain customer agreements which are favorable to the company. As far as personnel in sales, purchasing and administrative departments is concerned, the real problem of many companies is that often this personnel spends almost all of its time performing activities related to the management of external transactions and therefore not adding real value for customers. This leaves them little or no time for more productive and value-creating support activities. To further clarify our description of value-creating systems, different categories of activities will be represented using different styles, as shown by figure 6. N C S S P Realization Support to individual nodes Support at company level Support at system level Sales and purchases Set of activities Consumption activities Figure 6 - Activity representation FLOW CLASSIFICATION AND ARCS IN THE VALUE NET MODEL Beyond activities, the value net methodology aims at the simple presentation of flows which link activities to one another. Most of the models in industrial and strategic analysis have been conceived mainly thorough the consideration of physical flows of goods. In the "Information Era", however, competitive advantage is not only linked to the efficient flow of goods. It is importantly linked, as well, to the companies' abilities in managing information. 14 Besides that, any effective representation of value-creating systems should also include other relevant linkages, such as influence, reciprocal influence and financial flows. Therefore, after having defined nodes, it is necessary to identify relevant linkages within the value-creating system and represent them through the use of arcs. In order to make it easier to read the resulting picture, the use of different styles for different kinds of flows is recommended (see figure 7). $ Flows of goods Information flows Influence relations Reciprocal influence relations Financial flows Figure 7 - Flow representation Similar to activities, linkages in value-creating systems are also numerous. Their complete representation would hardly be feasible if only for the simple fact that the picture would be too complex to read. As far as representation of linkages is concerned, the following suggestions should be taken into consideration: only those linkages relevant to competitive advantage should be drawn; flows which differentiate value-creating systems competing for the same customer needs should be highlighted; flows corresponding to bottlenecks within the system should be highlighted; if the picture is too intricate, different kinds of flows should be individually represented, according to the kind of analysis being made. THE STRUCTURAL ANALYSIS OF NODES One of the most important contributions of the value net approach is the possible recovery of most concepts traditionally used in industrial structural analysis within a new perspective. An increasing number of industries is characterized by blurring boundaries and by the presence of competitors which are very different from one another in terms of background, positioning and make/buy/connect choices. In these kinds of industries (or clusters of industries such as, for example, telecommunication, information technologies, machine tool and factory automation, electronic publishing, entertainment) the use of traditional models is problematical and, sometimes, even impossible. It is not clear where the boundaries of the industry are and, above all, it is very difficult to find comparable competitors in terms of directly or indirectly controlled activities. Traditional structural analysis accepts that competitors could present different configurations (as this is one of the ways to differentiate competitive strategies). Nevertheless, tools such as Porter's five forces model imply the presence of a group of similar competitors. In the absence of such a condition, any analysis of the industry's cost structure (or of the strategic group's cost structure), as well as any analysis of the 15 power of suppliers and buyers would be meaningless. But who are buyers and suppliers if competitors have so very differently defined the activities to be performed internally? And how can industry's cost structure be evaluated if competitors use different technologies and perform very different sets of activities? In cases such as the ones outlined above, structural analysis has to be shifted from the industry level to the activity level, and the value net approach offers a good framework into which this kind of approach can be inserted. In the value net perspective, a company is seen as a sub-set of activities within a value-creating system. Profitability at the company level is therefore influenced by the individual structural attractiveness of controlled activities. From this perspective we can avoid all problems connected to the attractiveness evaluation of industries as a whole: an industry is much too wide a set of activities to be analyzed as an undivided entity. Moreover, it is often very difficult to clearly establish which activities are in the industry itself and which ones are outside. Furthermore, even in traditional and clearly bordered industries, the evaluation of industry attractiveness is the overall result of the average attractiveness of its individual activities. By shifting the analysis from the industry to the activity level, one can identify individual causes of attractiveness or non-attractiveness within the industry more easily. Shifting the structural analysis from industry to activities requires an adaptation of the determinants of attractiveness, as shown in figure 8. Activity Entry Barriers: • Economies of scale • Proprietary Know how • Brand identity of activity’s specific output • Government policy • Capital requirements Relations with upstream activities: • Concentration of upstream activities • Switching costs (both ways) • Differentiation of upstream activities’ specific output • Presence of substitute activities • Cruciality of upstream activities • Visibility of upstream activities • Complexity of information connected to the output of upstream activities Attractiveness elements at the activity level: • Cost structure/ Economies of scale • Concentration • Demand/supply ratio • Intermittent overcapacity • Proprietary know how • Differentiation and brand identity of activity’s output • Capital requirements • Exit barriers • Complexity of information of activity’s output • Cruciality of activity’s specific output • Visibility of the activity • Learning potential connected to the activity • Activity’s extendability Relations with downstream activities: • Concentation of downstream activities • Switching costs (both ways) • Differentiation of downstream activities’ output • Cruciality of downstream activities • Visibility of downstream activities Substituting activities: • Present relative price/performance ratio of substituting activities • Perspective relative price/performance ratio of substituting activities • Switching costs of connected activities Figure 8 - Elements of activity structure. 16 As figure 8 clearly shows, most of the elements to be considered in an analysis of activity structure are similar to those elements considered at the industry level. One exception is represented by two important determinants of attractiveness at the activity level: the learning potential connected to the activity and the activity's extendability. The learning potential connected to an activity is, especially from the dynamic point of view, a very important element of attractiveness that traditional analysis completely overlooks. Beside specific rivalry, cost structure and upstream/downstream relations, an activity could be very appealing from a structural point of view just because of the information one can gather and the knowledge one can develop in managing it. In the furniture industry, for example, the management of retail shops could represent a valuable source of information on customers' requirements and needs but, unfortunately, this potentiality is usually lost because of poor coordination between retailers and furniture producers. An example of innovative distribution systems aiming at overcoming such wasted potential is demonstrated by the "Divani & Divani" franchise (in english "Sofa & Sofa") recently established by Natuzzi, a leading company among upholstered furniture producers. Every visitor to a Divani & Divani shop is asked to complete a form with his or her personal data. If the visit does not result in a purchase, after a few days the shop's personnel phones the potential customer, asking why he or she made no purchase. All answers provided represent important input for product and service development: it is on the basis of such answers, for example, that Natuzzi has recently developed a new, low cost couch model, which has become a bestseller in Natuzzi's range of products. Sometimes the performance of a certain activity not only presents a high learning potential, but also leads to the development of competencies which can be used in other value-creating systems and whose potential can therefore be extended and used in many ways. With reference to "Core Competence" literature, extendible activities often coincide with the research and development of those products Prahalad and Hamel (1990) identify as "core products", that is goods between core competencies and final products. As we have already seen with learning potential, the extendability of a certain activity - all other structural characteristics remaining the same - increases its attractiveness, as it enables the company to leverage its resources and competencies. APPLYING THE VALUE NET MODEL: THE FURNITURE INDUSTRY CASE The value net approach has an impact on strategic analysis both at the company and at the industry level. Moreover, it implies by definition a wider perspective, extended to the entire value-creating system(s) analyzed. This is why a comprehensive example of its use would require much more space than available in an introductory paper such as this. 17 Yet, in order to make the theoretical propositions presented above more concrete and understandable, it may be useful to present, in a very synthetic way, a practical case study1. A particularly interesting example of the insights that the value net perspective can offer is represented by the furniture industry. The reasons for this interest can be summarized as follows: in home furnishings, value-creation is very evenly distributed, as producers, retailers and final customers all play relevant and active roles in it; in Italy, as well as in other developed countries, the home furnishings industry is going through structural changes predominantly involving distribution, but also involving production. Hence, value-creating systems at different evolutionary phases can be observed; at present, an important barrier to information flows can be found between producers and retailers, and this has induced many actors to look for innovative value-creating system configurations. Within the broader furniture industry, we will focus on the upholstered furniture segment, in order to make the comparison of different value-creating systems more significant and clear. Before going on to present some examples of value nets in the furniture industry, it may be useful to summarize here the main phases required in a value net analysis, as this should make it easier to understand the meaning of the figures and examples presented later on. The value net methodology consists of the following steps: 1. definition of the market segment (and related customer needs) whose valuecreating system we intend to analyze; 2. the identification of activities, their aggregation and the definition of nodes; 3. the identification of flows and the definition of arcs; 4. structural analysis of nodes; 5. description of the boundaries of different actors in the system; 6. identification of bottlenecks and of inefficient nodes; 7. description and performance analysis of possible alternative value-creating systems competing on the same market segment; 8. analysis at the individual company level; 9. identification of improvements in company positioning; 10. identification of improvements and innovation opportunities at the system level. As the list presented above clearly shows, the first phase in value net analysis is the definition of the market segment being analyzed. This definition should be made in 1 The case study presented, together with other examples, is analyzed in a greater detail in: Cinzia Parolini, Rete del valore e strategie aziendali (Value Net and Business Strategy), Egea, Milano, 1996. Other case studies and examples based on the value net approach are described in the following papers presented at the 1996 SMS Conference: Mikkel Draebye, "Value-creating systems in Italian Electronic Publishing"; Carlo Alberto Carnevale, "Fuzzy Industries: a Software Model for Strategic Analysis of Value Creation Networks Based on Fuzzy Sets". 18 terms of groups of customers served and needs satisfied. As far as the latter is concerned, sometimes needs satisfied correspond to specific products, whereas other times the same need can be satisfied in different ways (the need to gather legal informations, for example, can be satisfied through books, on-line databases, CD ROMs and so on). In our example, the need for upholstered furniture of medium quality/price will be considered. The analysis presented refers mainly to Italian producers, even if some remarks could be extended to other countries as well. Figures 9 through 12 describe in a very synthetic and aggregated way the results of phases 2, 3, 5 and 7 of the above list. As a matter of fact, the figures represent nodes, the main and most relevant linkages among them, and the boundaries of the economic actors involved. Actors playing a leading role in the system are highlighted, using a thicker line for their boundaries. Figure 9 illustrates the traditional value-creating system for the production of medium quality/price upholstered furniture. Traditional producers (Medium quality furniture) C Concept design Retailers Designers C C Design Basic components Engineering Complex components Assembly Specialized firms C Marketing and Communication Multibrand representatives Sell in C Communication with stores Interior design Retailing Final transport and installation Consumption C Communication with customers Figure 9: The value-creating system involving most traditional producers of upholstered furniture in the medium quality segment The main characteristics of the type of value-creating system outlined by figure 9 can be summarized as follows: brand identity is very low; information and communication flows are limited and mainly downstream; this type of value-creating system is characterized by the complete absence of a leading actor; low brand identity makes it difficult for producers to communicate directly both with final customers and retail shops; both downstream and upstream communication is filtered by multibrand representatives; 19 in Italy, the presence of multibrand representatives is almost a necessity, as the retailing system is very fragmented and most producers sell to hundreds of shops; retail shops often complain both about producers (because they do not give adequate information on products and acknowledge neither complaints nor suggestions for improvement) and multibrand representatives (because they carry on exclusively "sell in" activities and are not well informed); producers often complain about retailers because, from their point of view, they do not understand their efforts in product development, they are not able to highlight the strengths of their products, and because they have poor selling techniques; the role of final customers is limited to choice and consumption. The value-creating system described above is undergoing serious problems. Some of these are common to other types of value-creating systems competing in the upholstered furniture market, whereas others are specific (or particularly challenging) to medium quality traditional producers described above. In order to make this point clearer figures 10 and 11 should be considered. Furniture producers N Large low price stores S Engineering Marketing Basic components Specialized firms Complex components C Assembly Marketing and Communication Retailing Final transport and Installation Consumption S Communication with customers Figure 10: The value-creating system involving most traditional producers of upholstered furniture in the low end segment Figure 10 describes the value-creating system typical of the low end segment. In this case, the value creating system has a leading actor (large low prices stores) which, even if loosely, coordinates the system: it selects the producers coherent with its marketing concept, it gives producers precise ideas on the kind of furniture their shops can sell, it has an essential role in establishing prices for final customers. Moreover, in this type of system the connection between producers and retailers is direct and barriers to information flows are much lower. 20 Traditional producers (High quality furniture) C Concept design Designer Architects C C Design Basic components Engineering Complex components Assembly Specialized firms C Marketing and Communication Multibrand representatives Sell in C Communication with stores Retailers Interior design Retailing Final transport and Installation Consumption C Communication with consumers Figure 11: The value-creating system involving most traditional producers of upholstered furniture in the high end segment Figure 11 describes the value-creating system typical of the high end segment. This case is much closer to the first one presented (traditional medium quality segment) than to the second one (low end segment). In this kind of value-creation system, such as in the medium quality segment, the relation between producers and retailers is intermediated by multibrand representatives, which slows down the information process considerably. In the high end segment, however, higher brandawareness and higher visibility enable producers to select retailers, choosing the ones which more closely fit their marketing concept. They can also establish direct contact (even if a loose one) with architects (who have an important influence on the buying process) and with final customers through one-way forms of communication (mainly advertising, articles on specialized magazines, technical literature for architects). Also in this case, information flows are mainly downstream. Figures from 9 to 11 clearly illustrate the problems furniture producers (and particularly medium quality ones) face. The value-creating systems in which they participate present an intrinsically inefficient structure through which many opportunities to create value are lost. The system as a whole fails to gather information from the market, fails to use such information for product and service development and is characterized by a complex order gathering process, where errors and delays are frequent. This results in long lead time, a process of product development which is not guided by customers' suggestions, actors (such as multibrand representatives) that fail to add value which is proportionate to their cost, difficulties in making the final customers perceive the efforts made in product development and so on. What is worse, the individual actors in this segment have serious difficulties in changing their situation, as nobody in the system is in the position to take the lead. This is particularly true for the medium quality segment. Whereas in the low-end market well-managed, large retailers have succeeded in enhancing the productivity and 21 the effectiveness of their systems, and whereas high-end producers have a greater number of tools to influence the value perceived by final customers, the traditional medium quality segment has no leading actors capable to of re-engineering the entire process. Furthermore, in Italy the limited dimensions of both producers and retail shops make innovation efforts at the system level difficult, whereas innovations at the company level present too limited a scope to resolve the problems outlined above. In such a situation, many Italian companies are trying to introduce innovations at the system level, by changing the relations between producers and retailers. Such attempts are carried on in every segment of the market but, as illustrated above, seem to be more urgent in the medium quality segment. As far as this particular segment is concerned, an interesting attempt is the one led by Natuzzi, a producer of upholstered furniture based in southern Italy and well known world-wide. The value-creating system led by Natuzzi is described by figure 12. Natuzzi Franchisees Divani & Divani S S Concept design S S Consumers data base S Franchising formula management Information gathering Communication with the customers Specialized retailing Final transport and installation Architects S S Design Basic and complex components Exclusive suppliers Assembly Retailers Interior design Engineering Show room Final transport and Installation Traditional retailing Consumption Sell in C Marketing and communication Communication with stores C Communication with customers Multibrand representatives Figure 12: The value-creating system led by Natuzzi Figure 12 can be illustrated as follows: compared to other furniture producers, Natuzzi performs a greater number of activities internally. This can also be explained by the fact that the company is located in an area in which few subcontractors are available; production takes place on a just-in-time basis, and only on receipt of dealers' specific orders, allowing for low inventory of raw materials and no inventory of finished goods; 22 figure 12 describes not one, but two value-creating systems, with some of the activities common to both. One of these is of the traditional type, whereas the other is characterized by the presence of a retail franchising chain; as far as foreign countries (mainly USA a EU countries), Natuzzi distributes its products mainly through multibrand representatives (or, sometimes, through controlled trading companies) and traditional retailers. In most of the countries where Natuzzi exports, however, the retailing system is more advanced and less fragmented than in Italy and this reduces some of the problems underlined above; the most innovative element in Natuzzi's value net is represented by the franchisee "Divani & Divani". Started up in 1990, by 1996 this franchising chain had opened 65 shops in Italy and a few others in Portugal and Venezuela, with the opening of numerous other stores expected in upcoming months; in a "Divani & Divani" store, final customers and sales personnel can define together and visualize on a screen (with the support of customized software) the exact characteristics of the product. At order acceptance, this data is sent via modem to headquarters and the production process begins; as already illustrated above, the data systematically gathered through "Divani & Divani" shops is also used in new product and service development. Even if dealt with in a very synthetic way, the upholstered furniture example has enabled us not only to illustrate the methodology but also to highlight some of the advantages presented by the use of the value net approach in strategic analysis. Activities that create value for the customers can be represented in an effective way and possible alternatives for reaching the final customer can be easily highlighted. But what is more important is that this approach does not allow a limited perspective and obliges to take into account the entire system as well as various different actors participating in it. This approach provides the best basis from which to reconsider the boundaries and flows of present actors. Moreover, from this basis, a clear analysis of attractiveness can be made. We did not develop this point with regard to the furniture example because of space constraints, however it would be of utmost interest to take, for example, the activities in Natuzzi's value net one by one, disaggregate them further (if necessary) and then evaluate their attractiveness on the basis of the elements presented in the previous paragraph. 23 CONCLUSIONS The concept presented in this paper represent the earliest results of a larger research project aimed at developing new tools for strategic analysis. It is our conviction that, at the present stage, our research has succeeded in laying down the basic conceptual framework upon which one can start working towards the conception of operational tools suited to the "new economy" and useful in helping companies deal with an increasingly complex and dynamic environment. Our research is still under the way and is now focused upon performance and structural measures at the value-creating system level, as well as on the development of software tools designed to support value net analysis. 24 BIBLIOGRAPHY ABELL DEREK F., Defining the Business: The Starting Point of Strategic Planning, Englewood Cliffs, Prentice-Hall, 1980. AIROLDI GIUSEPPE - BRUNETTI GIORGIO - CODA VITTORIO, Economia Aziendale, Bologna, Il Mulino, 1994. ANDREWS KENNETH R., The Concept of Corporate Strategy, Homewood, Irwin, 1971. ANSOFF H. IGOR, Implanting Strategic Management, Englewood Cliffs, Prentice-Hall, 1984. BETTIS RICHARD A. - HITT MICHAEL A., The New Competitive Landscape, Strategic Management Journal, Volume 16 - Special Issue Summer 1995. BLACKBURN JOSEPH D. (editor), Time-Based Competition. The Next Battle Ground in American Manufacturing, Homewood, Irwin, 1991a. COASE RONALD H., The Nature of the Firm, Economica, 4, 1937. CODA VITTORIO, L'orientamento strategico dell'impresa, Torino, UTET, 1988. DAVENPORT THOMAS H., Process Innovation. Reengineering Work through Information Technology, Boston, Harvard Business School Press, 1993. DAVIDOW WILLIAM H. - MALONE MICHAEL S., The Virtual Corporation: Structuring and Revitalizing the Corporation for the 21st Century, New York, Harper Collins Publishers, 1992. DEMSETZ HAROLD, The Theory of the Firm Revisited, in The Nature of the Firm, Williamson O.E. - Winter S.G. (editors), New York, Oxford University Press, 1991. DRUCKER PETER F., Managing for the Future: The 1990s and Beyond, New York, Dutton, 1992. FORRESTER JAY W., Principles of Systems, Cambridge, Mass., Wright Allen, 1968. GRANDORI ANNA - SODA GIUSEPPE, Inter-firm Networks: Antecedents, Mechanisms and Forms, Organization Studies, 16/2, 1995. HAMEL GARY - PRAHALAD C.K., Competing for the Future, Boston, Harvard Business School Press, 1994. HAMMER MICHAEL - CHAMPY JAMES, Reengineering the Corporation: A Manifesto for Business revolution, London, Nicholas Brealey Publishing, 1993. JARRILLO CARLOS J., On Strategic Networks, Strategic Management Journal, Volume 9, 1988. LORENZONI GIANNI (editor), Accordi, reti e vantaggio competitivo, Milano, Etas Libri, 1992. NORMANN RICHARD - RAMIREZ RAFAEL, From the Value Chain to the Value Constellation: Designing Interactive Strategy, Harvard Business Review, JulyAugust 1993. NORMANN RICHARD - RAMIREZ RAFAEL, Designing Interactive Strategy: From the Value Chain to the Value Constellation, Chichester, John Wiley & Sons, 1994. PAROLINI CINZIA, Rete del valore e strategie aziendali, Milano, Egea, 1996. PENROSE EDITH T., The Theory of the Growth of the Firm, New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1959, (ultima edizione: Oxford, Basil Blackwell, 1995). PORTER MICHAEL E., Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors, New York, The Free Press, 1980. PORTER MICHAEL E., Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance, New York, The Free Press, 1985. 25 PRAHALAD C.K. - HAMEL GARY, The Core Competence of the Corporation, Harvard Business Review, May-June, 1990. SENGE PETER M., The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization, New York, Doubleday/Currency, 1990. SHANK JOHN K. - GOVINDARAJAN VIJAY, Strategic Cost Management, New York, The Free Press, 1993. STALK GEORGE JR. - HOUT THOMAS M., Competing Against Time: How Time-Based Competition Is Reshaping Global Markets, New York, The Free Press, 1990. TAPSCOTT DON - CASTON ART, Paradigm Shift, New York, McGraw-Hill, 1993. WERNERFELT BIRGER, A Resorce-Based View of the Firm, Strategic Management Journal, Volume 2, 1984. WILLIAMSON OLIVER E., Markets and Hierarchies: Analysis and Antitrust Implications, New York, The Free Press, 1975. WILLIAMSON OLIVER E. - WINTER SIDNEY G. (editors), The Nature of the Firm, New York, Oxford University Press, 1991. 26