Discussion - London South Bank University

advertisement

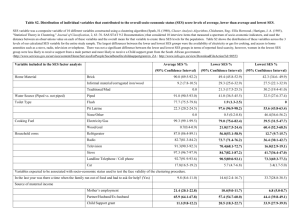

Social Enterprise: The Research Challenge A Discussion Paper Professor Ken Peattie and Dr. Adrian Morley April 2008 BRASS Research Centre Cardiff University 55 Park Place, Cardiff CF10 3AT Tel: [00 44] (0) 2920876562 Fax: [00 44] (0) 2920 Email: peattie@cf.ac.uk www.brass.cf.ac.uk 1. Introduction. This discussion paper has been prepared as a companion piece to the research monograph “Social Enterprises: Diversity & Dynamics, Contexts and Contributions” (Peattie and Morley, 20081) and provides an opportunity to discuss some of the key issues raised in the monograph, and during the 2007 ESRC/Social Enterprise Coalition seminar series (for further details see the Appendix). It also aims to consider the future development of research in the social enterprise field in the UK in terms of capacity building, knowledge transfer and potential priority sectors and issues for future research. 2. Engaging UK Business Schools in Social Enterprise Research. Since SEs represent organizations that operate in business, albeit with social aims, it would be logical for business schools to be leading the way in SE research. In the USA there is a concentration of SE expertise in one or two of the longest established and most prestigious business schools, particularly Harvard and Columbia. There is also a strong link there to the international development agenda, particularly through Latin America, pursued through links between leading North American and Latin American Universities2. In the UK, there is a tendency for SE research to focus more on relatively local issues, and for engagement within Universities to centre around (usually postgraduate) teaching programmes. Research interest in SE tends to be stronger in business schools within newer universities, and interest generally is often as strong or stronger within geography departments (e.g. at Durham or Hull Universities). Business Schools with a significant teaching or research interest in SE include: Manchester Metropolitan University Business School (Centre for Enterprise); London South Bank University (Dept of Business, Computing and Information); Liverpool John Moores University (School of Management); London Business School (Global Entrepreneurship Monitor); Heriot Watt University (Social Enterprise Institute); Caledonian Business School (Glasgow Caledonian University); Oxford Said Business School (Skoll Centre for Social Entrepreneurship); The Judge Business School, University of Cambridge; Nottingham University Business School; Open University (Co-operatives Research Unit); University of Brighton Business School; Huddersfield University Business School; University of Wales Institute Cardiff (UWIC) Business School (Wales Institute for Research into Co-operatives) ; BRASS Research Centre, Cardiff (Schools of Business, Law and City and Regional Planning); The comparative lack of engagement with the SE research agenda amongst most UK business schools might seem curious given the significance and growth of SEs in practice. The probably reflects the structures and history of UK business schools, the structure of the SE research field, and the effect of recent ‘Research Assessment Exercises’ (RAEs) on business school priorities and research agendas. The structures of business schools tends to reflect functional aspects of business with courses and groupings for purposes of teaching, research and administration reflecting particular disciplines such as human resources, accounting, operations or marketing. There will also be courses and groupings that consider businesses from a more holistic perspective (such as strategic management), at an aggregate level (via economics) or which consider particular types of business (e.g. service businesses, small businesses or sector specific businesses). The nature of the RAE is also very discipline bound and in relation to business and management recognizes the following ‘units of analysis’ (UOA): accounting and finance, business history, business and industrial economics, employment relations, entrepreneurship and small firms, human resource management, information management, innovation and technology management, international business, management education and development, management science, marketing, operations management, organisational psychology, organisational studies, public sector management, service management, strategic management; and any other field or sub-field aligned to business and management. As much of the literature about SE (including the research monograph) demonstrates, SE does not belong specifically within any of these UOAs, although it has clear links to the entrepreneurship and small firms and to the public sector management UOAs in particular and there have been particular studies that address the organisational studies and strategic management agendas. The other key aspect of the RAE is that it is strongly weighted to judging research quality in terms of publications in established journals that are highly ranked for quality (and although there is no single definitive list or ranking, there are a number of lists circulating that have been generated through peer review or by statistical analysis of previous RAE results3,4). This leads to a concentration of publication effort into a relatively narrow range of journals (given the breadth of the UOAs listed above), with around half of the nearly 10,000 submissions to the 2001 RAE appearing in only 126 leading business and management journals 3. This situation creates something of a “Catch 22” for the development of new journals in emerging research fields. Authors are likely to be deterred from submitting good quality research to journals that lack a strong potential ranking in RAE terms, and a journal will not be considered strong in RAE terms unless peers recognise the quality of publications appearing within it. This is a recipe for the ossification of disciplines, and this situation will hopefully change once the 2008 RAE is completed. 3. Engaging Business School Academics in the SE Research Agenda. Partly because of the “Catch 22” that makes it difficult for new disciplines to become established, there is a dilemma for researchers working in, or interested in entering into, SE research. The establishment of the Social Enterprise Journal as a refereed academic journal is a major step forward in establishing SE as a recognised sub-discipline, although like any newly established refereed journal, it may take a little time before its quality in terms of published research is matched by a strong perceived RAE related ranking. Given the relatively small number of people working in the field, this creates dilemmas. For individual researchers it makes sense for them to pursue publication in more strongly ranked RAE journals. Although in the past SE publications have generally been conspicuous by their absence within the top business and management journals 5, in future more enlightened editors may be open to publishing articles as the field becomes more established and becomes acknowledged as a ‘gap’ in journals coverage. This ‘catching up’ process could happen through a range of journals printing individual papers, or through particular journals establishing a special issue on SE (as was the case with the Journal of World Business in 2006). The former course would contribute to the continued fragmentation of the field, and while the latter could be academically helpful in the short-term, both could deprive the SEJ of the good quality publications it needs to develop and grow in stature and recognition. Interestingly during 2007 the Association of Business Schools (ABS) sought to develop a standard ranking of academic journals. During the consultation the Institute for Small Business and Entrepreneurship (ISBE) 6 was unhappy at the relatively low draft ranking accorded to some of the more established journals specializing in smaller businesses including International Small Business Journal; the Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, and Environment and Planning ‘C’ (a strongly recognized journal in the field of geography and planning that includes a small business and entrepreneurship remit). 4. Linking Business Schools and Social Enterprises. Achieving better linkages between business schools and social enterprises will be an important step towards further developing the SE research agenda. This could be achieved in a number of ways, for example through initiatives to connect all business schools to their local SE population. This could involve the provision of business advice to SEs, the involvement of SEs in teaching programmes or using SEs as the focus for practical student projects or action learning initiatives (The authors’ personal experience is that making a connection with a SE can lead into a mutually beneficial relationship that generates opportunities for research. A chance conversation with the founder of the SE Global Ethics, who are behind the ONE ethical water brand, led to the development of a case study, conference papers and a journal article featuring the enterprise, and it acting as the focus for two postgraduate student research projects that produced valuable results for Global Ethics). Targeted funding of research support for business school/SE research collaborations, perhaps on a competition and/or regionally distributed basis could also encourage more engagement between the two. It would also be helpful to create greater awareness within business schools about the importance of SEs to the economy at a local and national level, and the extent to which they represent opportunities for new and innovative research projects. An underresearched field represents a research and career opportunity for academics, providing there are opportunities and resources for research, and suitable channels and opportunities for publication. Communications efforts to build the profile of SEs and featuring the opportunities for innovative and socially valuable research through the Association of Business Schools, and channels dedicated to key sub-disciplines such as small business management, marketing, HRM and accounting would be potentially valuable. 5. The Research Agenda : Understanding Key Dimensions of SE. Haugh’s review of the future research agenda needs for SE7 highlighted the need for research into the nature of SEs, how their environment impacts upon them, and how they emerge, organize, acquire resources, develop and learn. Key challenges in tackling these aspects of the SE research agenda include : Building and transferring knowledge upwards from SE sub-disciplines. The relationship between the research literatures for social enterprise as a whole, and for some of the sub-types of social enterprise within it, reverses the conventional research development path for business disciplines. Conventionally a generic field develops and is then sub-divided with the emergence of sub-disciplines. To take the example of marketing, the discipline of marketing emerged as a generic field, and then sub-divided with the establishment of services marketing, tourism marketing, bank marketing, notfor-profit marketing, political marketing etc. In each case the sub-discipline has a smaller, more tightly focused and less mature research literature than for the parent discipline. In the case of SE, there are larger and more mature bodies of research literature available for cooperatives, FairTrade organizations, credit unions, housing associations and charity retailing than exists for SE per se. This will make it important to better understand the differences and similarities between and amongst particular types of SE. This will help to allow knowledge transfer between SE sub-disciplines, and transference to the development of the generic field of SE (in much the same way that a clearer understanding of the differences and similarities with mainstream businesses will determine how much mainstream business research insight can also be applied to SEs). The impact measurement challenge. A pressing challenge for the SE research community is to develop methodologies that allow SEs and their stakeholders to measure and communicate SE’s broad based impacts in a meaningful, efficient and effective manner. As explored in the research monograph, this is important for: Self diagnosis; Public sector contract demands; Communicating with the private sector; Encouraging participation from consumers; Attracting potential social entrepreneurs to the sector; This need exists despite the fact that many aspects of the benefits that SEs provide are accepted almost unanimously by stakeholders, including much of government (particularly at the national and regional level) and private business. This was a theme that was raised often during the seminar series as both sector representatives and public agencies stressed the need to be able to formalise these benefits. Despite this apparent need, it has been observed that the importance of developing new ways of measuring social as well as economic SE benefits represents ‘something of a backwater’8 in terms of research. At the level of the firm, stakeholders increasingly demand ‘hard factual evidence’ from SEs in exchange for grants, income, participation or support. This issue, and the challenge of meeting it in practice, is a recurring theme in the literature and also recurred during the seminar series. There are undoubtedly some impacts such as ‘esteem raising’, ‘sense of community’ and ‘inducement of behavioural change’ that are likely to remain difficult to quantify in any meaningful way. In practice, some commentators such as Hart and Houghton9, even question the validity of attempting to estimate SE impacts on an aggregated basis in order to ascertain values connected with the sector or its sub-sectors. The sheer breadth and diversity of activities and strategies in the sector may doom to failure attempts to develop universally applicable and consistent approaches to benefit measurement. As the research monograph describes, there are a number of methodologies being developed and refined that aim to meet some of the measurement needs for SEs. These include Social Return on Investment, Expanded Value Added Statements and Ongoing Assessments of Social Impacts methodologies10,11. Again these methods have been largely transposed and adapted from conventional business accounting tools. Jeremy Nichols summed up the research challenge when he recently observed that such methods are striving “to achieve a level of complexity to the answer that has taken the accounting profession 100 years, a profession still debating the correct way to account, for example, for derivatives.” 8 Ultimately, if the real value added to society of different SE models is to be identified then these methods will need to be tailored for conventional business solutions as well as alternative ones such as SEs. Strategy, structure and culture. The relationship between organizational strategy, structure and culture is a key focus for research in conventional management research and represents an important area of linkage between the fields of strategic management and organizational behaviour. The interplay between these issues has not yet received sufficient attention for SEs as a whole, although there are relevant studies relating to particular forms of SE such as cooperatives or mutuals. The impact that the primacy of social purpose has for SEs on organisational strategy and culture, and how some of the typical characteristics of SEs (such as the mix of volunteers and workers, and the relatively participatory and democratic style) on organisational structure will be important areas for research. One interesting cultural dimension will involve seeing how the SE related research on social entrepreneurship, with its emphasis on the entrepreneur as an individual, and the SE research stream that has emerged from the cooperative movement, with its emphasis on collectivism, can be reconciled within a broader understanding of SE research. SE development and evolution. Haugh 7 identifies how SEs grow and develop as an important area for future (particularly longitudinal) research, and it is one in which differences may exist to conventional enterprises. How to grow and/or replicate successful social enterprise business models is an area of increasing interest for policymakers, practitioners and researchers, as is the use of particular growth strategies such as social franchising. The problems that SEs often experience in terms of security of income and gaining access to additional funding from lenders or through equity can make organic growth difficult. Growth by acquisition and merger is a commonplace strategy in commercial market, but is less used, more contentious and less well understood in a SE context. Growth through merger and acquisition has occurred in the Credit Union sector (largely because of regulatory pressure and sustainability problems experienced by small Credit Unions), but the phenomenon has yet to be researched and analysed in a meaningful way 12. Given the increased interest in corporate social responsibility strategies and cause-related marketing amongst commercial businesses, it is also likely that suitable social enterprises may also find themselves potential targets for acquisitive interest amongst commercial companies (as happened with the acquisition of the ‘Ethos’ ethical water business by Starbucks). The implications of such acquisitions and what they mean for the social mission of the enterprise, and what SEs can do to avoid acquisition in terms of legal structures and strategies, could also form an interesting topic for research. In Bull’s (2006) review of social enterprise13 he highlights several factors in the evolution of SEs over time, and in particular how the combination of a shift away from an environment based on grant aid to one based on a ‘contract culture’, forces of isomorphism pushing SEs towards ‘conventional’ commercial business models, cultural change over time (particularly in the face of increasingly competitive markets), and increasing pressures towards ‘professionalisation’ within the sector are making it increasingly difficult for SEs to maintain their cultures, their focus on community needs and the primacy of their social mission. The interplay of these forces, and the impact that they have on the different dimensions of SEs will also form a valuable future area for research. 6. The Research Agenda : Understanding the Environment for SEs. As the point Bull makes above demonstrates, the environment within which SEs exist fundamentally shapes their nature, strategies, structures and their prospects for survival, growth and sustainability. The rapidly changing policy and regulatory environment for SEs, obviously offers considerable scope for future research that examines the impacts that these environmental changes have had. It also creates opportunities for research which goes beyond considering SEs as organizations to consider them as parts of wider socio-economic and cultural systems. As such SEs have already attracted the interest of sociologists, political scientists, economists and geographers, and there will be future opportunities to engage more researchers from these and other social science disciplines. There are a number of specific elements of the environment for SEs that are particularly likely to generate future research needs and opportunities, including: Public sector service delivery. A clear driver behind much current interest in SEs amongst the policymaking community is the perceived latent potential of SEs as deliverers of public services. This is particularly evident in the national context through the priorities of the Office for the Third Sector and the National Health Service. As the accompanying monograph highlights, the current policy rhetoric clearly identifies the added value that SEs can bring to public service delivery. This is reflected by the identification of ‘local service delivery’ in the official UK SE strategy as one of three key policy drivers (along with ‘social cohesion’ and ‘competitiveness & enterprise support’). Indeed, the evolution of large parts of the sector appears, at first instances at least, to be linked to opportunities to become public sector service deliverers in one form or another. The health, social care and child care SE sectors in particular have developed in recent years with a firm stance towards public sector engagement and its associated income opportunities. This process of engagement between then public sector and SEs has been partially driven by the existence of a small number of successful ‘poster children’ for the sector whose activities and impacts have been well documented, largely in case study format. Such enterprises tend to be significantly more successful than average SE in their sector, particularly in terms of impacts based on standard cost-focused metrics. There appears to be opportunities to take a more in-depth analytical approach to understanding what makes these businesses so successful, and in particular, disassociating entrepreneurial, enterprise and supporting environment factors. More generally, questions remain about the value added that SEs can bring to public sector service delivery and the long term impact of these kinds of relationships for SEs themselves, both individually and as a sector. More work is needed to ascertain the distinct benefits SE business models can provide compared with both traditional and other alternative models of service provision. The development and refinement of comparative assessment methodologies and their effective application and communication is a key part of this area of research enquiry. The prevailing government view of the role of SEs in public service provision is set out in the 2006 action plan ‘Scaling New Heights’14: “At their best, social enterprises can offer a high level of engagement with users and a capacity to build their trust. They are also a valuable source of innovation – including for services they do not delivery directly. Public services learn from the problem-solving spirit of social enterprises, which can help improve the quality of public services by shaping service design and by pioneering new approaches that can influence the way services are delivered by the public sector.” [p17] Despite this rhetoric, the question remains to what extent is it realistic, and effective, for governments to use SE in public service delivery as a means of delivering on wider social and environmental aims. Evidence beyond the subjective and anecdotal that can contribute towards our understanding in this area is currently thin on the ground. Distinctions need to be made between what SEs can be ‘at their best’, what they are typically, and how this compares with other models. This understanding is vital both in terms of providing effective support for such structures, evidence to promote interest in SEs, and to ensure value for money (in its broadest possible sense) for the public purse. An additional element outlined in the research monograph is the longer term impact of SE involvement in public services on the nature and strategies of both public sector institutions themselves and competing commercial models of service provision. This links more generally with issues surrounding the influence of SE activity on conventional business practices and consumer behaviour. Tendering processes. An important aspect that impinges on the current policy interest in SEs playing a greater role in public service delivery, is their ability to bid for and win business from public institutions, usually through tendered contracts. Many of the issues faced by the SE sector regarding public procurement are shared with small businesses more generally. These include factors such as the greater use of aggregated contracts, skills and knowledge requirements, resource demands associated with protracted tender processes, and procurement regulations that restrict the use of social and environmental clauses. Guidance and general interest in these issues relating to small and local businesses is generally more developed than for the SE sector. The Office of Government Commerce, for example, is one among a number of organisations who provide published guidance 15. Beyond these, however, there are a clear set of issues that SEs face by dint of their institutional nature. These revolve largely around disadvantages resulting from the employment of narrow metrics in contract decision making that make it difficult for SEs to gain from their broader, largely non-quantifiable economic, environmental and social contributions. This situation appears to be often compounded by a lack of accounting culture and conventional business rigour that means supporting data is not routinely gathered16. Academic research has a role to play in investigating and assessing the range of business arrangements open to public institutions and their service or goods suppliers and the impacts of these forms on SEs. Public Private Partnerships, Service Level Agreements, Framework Agreements and traditional Service or Goods Contracts all have particular dimensions that potentially disadvantage SEs. Research into appropriate public procurement structures for SE should address the apparent conflict at the heart of government and policy between the market rationalising efficiency agenda, typified by the Gershon report and the movement towards the greater use of public procurement to promote the sustainability agenda, typified by the work of the UK Sustainable Procurement Task Force and the emphasis of a growing number of advocacy groups. In short, the strategic nature of public procurement needs to be better understood in terms of supporting and maximising the value of the SE sector. Business support provision. One of the key developmental issues for the sector as a whole is a perceived lack of effective support structures set up to assist SEs. A number of research publications have identified this issue and indeed the UK government itself recently acknowledged the weaknesses in current support provision as the following: fragmented and inconsistent infrastructure; weaknesses in the ability of mainstream business support infrastructure in engaging with and responding effectively to SEs an existing need for SEs to be able to access high quality business support17. Poor perception and uptake of services by the sector may appear to go hand in hand but there is evidence to suggest that part of the problem may be due to a prevailing social entrepreneurial ethos that to a certain extent rejects ‘mainstream’ solutions. Alternative forms of support, typically through socially based ‘bottom up’ networks, appear to be preferred by many entrepreneurs and their organisations. This raises the notion that there is a limit to the effectiveness of conventional business support models that is independent of their quality and resources. This all implies a need for a greater research effort into alternative support structures based on peer-to-peer systems. Again, there is some overlap into issues concerning small commercial businesses, some of which appear to value unconventional support networks above more formal provision. There is clear potential for knowledge exchange and learning from existing academic literature in this area aimed at conventional small businesses. Additionally, as the research monograph sets out, there is an apparent research need to address localisation issues that appear to influence support needs and outcomes and the interaction of these aspects with sectoral issues. It is also of interest to note that little evidence exists of the benefits of academic work ‘trickling down’ to individual SEs or to their immediate service providers18. This points to a need for a greater focus on knowledge transfer to the grassroots level by the research community, including tailored events and research derived documents developed for a practitioner audience. There would appear to be potential benefits for more direct one-toone contact including the promotion of action research approaches. Financial support. The financial support of SEs, whether income based or grant funded is an issue that was repeatedly brought up during the seminar series. The key to understanding financial support needs and appropriate models of their provision would appear to be the development of effective SE business development models. Existing literature points to the importance of appropriate financing provision at key SE development stages including enterprise conception and start-up as well as dictating opportunities for expansion and impact optimization. Both grants and public income streams have the potential to be employed much more strategically than at present, for example by encouraging better social auditing or through targeted subcontracting stipulations with private sector partners. Academic researchers can play a key role in this, particularly through case study and best practice identification. 7. Opportunities for Capacity Development There are a number of opportunities that exist in relation to developing the research capacity within the SE field: Expanding opportunities. Virtually every commentator on SE seems to agree that it represents an area of increasing opportunity for entrepreneurship, business development, innovation and for meeting the needs of society, communities and policy makers. As SE grows as a phenomenon within business, communities and in relation to policy, so it will generate increasing research opportunities for academics in business, finance, geography, sociology, policy studies and other disciplines. It is clear from the research monograph that there is a great deal of research needed to provide policy makers, practitioners and the academic community with a better understanding of the role, nature, diversity, distinctiveness and contributions of SE and a clearer idea of how SEs emerge and develop, why some succeed and others fail, and finally what actions will help to expand and sustain the SE population. The size of the research opportunity is in contrast with the relatively small pool of researchers tackling it, and the future development is going to depend on expanding the number of academics involved in SE research. Partly this can be achieved through capacity building and encouraging a growth in the number of postgraduate students conducting PhD research in the field (although the small existing pool of researchers creates another constraint in terms of the number of available supervisors). The establishment of the new ESRC Research Centre on the Third Sector will provide potential critical mass for SE orientated PhD research. Alternatively capacity can be developed by encouraging academics currently researching in the mainstream into issues that are relevant to SEs, to adopt SE as a field for research. Topics such as SE governance, benefit measurement, human resources management, marketing, organizational development, financing and contribution to social inclusion or regeneration could be tackled by attracting specialists in these issues who have previously studied them in relation to mainstream, rather than social, enterprises. Achieving this is likely to require some mechanism to promote collaborative research between these potential SE scholars and those with experience in the field. A seedcorn funding scheme for SE research projects involving ‘new to the field’ scholars that favoured collaborative bids between established SE scholars and established scholars whose expertise had not previously been applied to the SE filed might be one means to achieve this. SE population expansion. The growth in the population of SEs should create opportunities for more quantitatively based research which will allow a move away from the reliance on small-scale, qualitative case-based research. To date the quantitative work has mostly consisted of mapping exercises, but in future there should be more opportunities to develop and empirically test research propositions that relate to SEs. However, there will be issues relating to (a) research design and sampling to create meaningful samples, unless we resolve the definitional problems that have dogged the sector, and that are explored in the monograph and elsewhere and (b) avoiding sampling ‘exhaustion’ in which SEs, who are typically run on an administratively very ‘light’ basis, find themselves the target of a succession of questionnaires or requests to be involved in case studies, research funding applications or student projects. New journals and publication opportunities. A number of relatively new journals have emerged with a focus on small business and entrepreneurship including Journal of Small Business and Entrepreneurship; International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation Management; Journal of International Entrepreneurship, and Journal of Enterprising Culture. Several of these were given a modestly strong suggested RAE ranking of 2 in the ABS draft rankings and this should provide opportunities for academics researching into SE to publish in journals with (at least potentially) a relatively attractive RAE rating. Ideally this will attract more academics to get involved in SE research, rather than spreading the publication efforts related to SE more thinly. The fact that these newer and/or relatively ‘unproven’ journals were given a relatively worthwhile RAE rating perhaps suggests that the ‘Catch-22’ observed earlier is not operating, but ironically the ISBE expressed surprise over this and suggested some ‘downgrading’ in their response. Development of the Social Enterprise Journal. The main SE journal was originally published through a sector body, Social Enterprise London, and this may have acted as a deterrent to academics interested in publishing in the area of SE looking for an outlet. It has recently become part of the Emerald stable of academic journals, which is likely to improve its attractiveness as a publication outlet to academic researchers. A social enterprise ‘Stern Review’. The experience of researchers working in social science areas such as business schools in relation to climate change in recent years is perhaps instructive. There is a long-standing natural science research agenda concerning climate change, and for many years there have been related social science contributions in mainstream business schools from academics perceived to be working on climate change as part of a ‘fringe’ or ‘alternative’ agenda. The publication in 2006 of the Stern Review19 authored by Sir Nicholas Stern, one of the UK’s most eminent (and mainstream) economists, pushed the issue of climate change up the mainstream political, economic and business school agendas with a sudden jolt. In many ways this echoed an earlier intervention in 1995 by Professor Michael Porter when he and Claus van der Linde published an article on sustainability and competitiveness20 that made sustainability a far more ‘legitimate’ issue for mainstream businesses management scholars to discuss. In developing a research agenda that underlined the potential importance and value of SE, there may be benefits in tempting someone with a major reputation in mainstream to act as the type of heavyweight academic ‘champion’ that Taylor’s review of SE research suggests would be useful21. Sustainable Development. Sustainability is another rapidly emerging aspect of scholarship that is of considerable interest to policy makers, but has been somewhat neglected in the teaching and research portfolios within universities (particularly their business schools), despite its importance in relation to business practice. In relation to SE, the emphasis has traditionally been inward-looking to consider the sustainability of SEs themselves, particularly from a financial perspective. There is a trend towards SE being considered as an integral component in the drive to create more sustainable communities within more sustainable economies and societies (something articulated in the WWF funded research work on ‘One Planet Living’ being led by the University of Manchester22). Given the increasing interest in the sustainability agenda, there are likely to be considerable opportunities for those working in SE to develop new relationships and synergies with researchers interested in sustainability. Interdisciplinarity. The lack of a neat fit between SE and existing disciplines has hampered its development. However, universities and funding bodies such as the ESRC have increasingly promoted interdisciplinary research, and in many cases have sought to identify suitable subject areas that would allow academics from different disciplines to work together. SE represents an area that could be used to bring geographers (particularly economic geographers), sociologists and economists together with scholars interested in the various management disciplines and issues of international development and sustainable development. This would help to ensure that SEs become better understood not just as businesses, but in terms of their social and political significance and the role that they play in broader systems of community, economy and place. 8. Conclusions. There is growing interest in the further development of research into SE being expressed by policy-makers and research funders (which this discussion paper and the accompanying research monograph are symptomatic of). This should create significant opportunities for new and innovative research in the field, however, to ensure that these opportunities are taken it will be important to achieve: Clarity in the field by moving past the ‘definitional debate’, which represents an unnecessary distraction and creates an impression of more confusion than actually exists; Distinctiveness, so that the distinctive nature and needs of SEs are better understood which will clarify the limitations of transferring knowledge from mainstream research sources as well as the opportunities. What is needed for the future is research which isolates the differences between SEs and conventional SMEs. The Bank of England’s report, The financing of social enterprises: A special report by the Bank of England, compared a sample of 200 social enterprises with a sample of conventional small and medium sized (SME) businesses 23. Such comparative research will help to unlock the value for SE that already exists in areas of the conventional business literature. One current trend is towards greater interest in the corporate social responsibility agenda amongst commercial SMEs24, and as that develops so the likely common ground between commercial SMEs and SEs is going to increase; International collaborations, in order to benefit from the research knowledge that has been accumulated elsewhere and to establish meaningful international comparisons. This will be done with care since there are international differences in the history, traditions and legal frameworks relating to SE amongst countries and regions; Resources being made available to instigate and support research; Incentives and mechanisms put in place for academics working outside the SE field to become more aware of, and involved in, the research opportunities it presents; Enthusiasm for research from SEs themselves so that they feel that they are partners in the production and use of valuable knowledge, rather than the subject of research for the benefit of others. Coordination between researchers and the SEC, who already play an important role in instigating, conducting and disseminating SE research, will be important for this. The ESRC/SEC seminar series collaboration was a good example of such integration and coordination; Bridge building across disciplinary boundaries to create ‘a richly connected field from what is currently a highly fragmented research scene’ 21. The aim of this discussion paper and the accompanying monograph was to provide a structured review of the existing SE research field and future opportunities and priorities for developing SE research and knowledge transfer. This paper, the research monograph, and the research seminar series from which both sprung, will hopefully spark further debate and discussion that will provide new ideas on how to achieve a richly connected future for research into SE that creates knowledge of value to all the stakeholders concerned. Appendix - 2007 SEC/ESRC Social Enterprise Seminar Series Summary During Summer/Autumn of 2007 The Social Enterprise Coalition (SEC) and the Economic & Social Research Council (ESRC) collaborated in organising and hosting a Policy Research Seminar Series across the UK and the English Regions. The purpose of the seminar series was: To inform the production of a monograph on social enterprise research; To engage practitioners, policy-makers and academics on the importance of, and need for, high quality research in the future; To identify the research priorities of practitioners, policy-makers and academics as stakeholders. The seminar series involved seven seminars, one in each UK country and 3 in the English Regions, on the following topics: Social Enterprise Dynamics And The Economy: 1. Belfast 2. Cardiff 3. Westminster 4. Edinburgh - 27th June, - 12th July: - 17th July, - 11th September, Social Enterprise In Public Services – Employee Owned Organisations & Professional Partnerships: Sheffield Social Enterprise In Public Services: Manchester Impacts And Return Of Social Investment: Milton Keynes - 27th September - 9th October - 11th October Contributors: The seminar series attracted a range of contributors from the fields of practice, policy and research relating to social enterprise, including: Jonathan Bland, SEC; Rebecca Challoner, Social Enterprise Unit, Department of Health; Hilary Graham, OTS; Brian Howe UCIT; Jim Johnston, Strategy Manchester, NWDA; Nigel Lowther, Hill-Holt-Wood; Anna MacAleavey; Stephen MacDonald, DETI; Professor Pete Marsh, University of Sheffield; Professor Alan McGregor, University of Glasgow; Dr Adrian Morley BRASS Research Centre, Cardiff University; John Oates, Brag Enterprises; Professor Rob Paton, The Open University Business School; Professor Ken Peattie, BRASS Research Centre, Cardiff University; Geoff Pope, Scottish Executive; Michelle Rigby, Social Enterprise in East England; Markia Rose, The Social Enterprise People; Nick Starkey, Analysis & Research, Office of the Third Sector; Antonia Swinson; John Wilkinson, East of England Development. Summary of Themes & Issues Raised Within the Seminars. The seven SEC/ESRC seminars and the presentations within them generated considerable interest and debate, and raised many points which were valuable in considering how to shape a future research agenda for SE. The following points seek to collate a range of the points raised in relation to key themes: Terminology The need for a clear and universal SE definition was highlighted in several seminars along with the need to understand what distinguishes them from other types of organisations (both within markets and within the third sector), and there were also conflicting views about the meaning and implications of the concept of 'profit', particularly for the SE sector. It was interesting that in the devolved administrations the backdrop of the discussions was the concept of the social economy rather than just social enterprise. With the inclusion of social enterprise in the term ‘third sector’, the continued use and development of the term ‘social economy’ could be usefully explored. One commentator described social economy being seen as ‘economics for the marginalised’. Public Services There were two seminars that specifically focussed on public services, though it arose at every seminar. Key areas of discussion were: Public sector procurement: at present it is too costly and complex for many SE’s to participate, there needs to be greater efficiency and national consistence with procurement processes; commissioners are not good at specifying the outcomes they want; a lack of mechanisms to be able to share financial benefits/savings across the local economy; understanding the role Councillors have in the procurement process, and how their skills and/or knowledge can be developed to allow them to understand the process of commissioning for well-being (wider community benefit) rather than just for a service; the importance of the relationship between the commissioner and commissioned, and of social networks within the procurement process; the importance of perceived risk in the procurement process and whether SEs are perceived by some commissioners as higher risk alternatives; how have Local Authorities that have commissioned SEs services dealt with standing orders for procurement and tendering i.e. those services of more that £10k p.a. that are put out to full competitive tender? how to build commissioner confidence and trust, and to communicate to commissioners the capacity, skills and entrepreneurial nature that SEs possess to enable them to effectively deliver services. Also the importance of the SE sector demonstrating their capacity, impact and added value to put this across; the potential to share knowledge with non-SE small firms who may share similar characteristics and experiences. Public services delivery: has the public got ‘preferred models’ of public service delivery ie who should or should not provide public services ? are social enterprises just private organisations that are part of the privatisation agenda ? how surpluses or profits are used is crucial to this understanding. What role can SEs play in addressing health inequalities by targeting areas of deprivation to ensure that the health and social care sectors also provide employment to disadvantaged individuals and provide jobs which are flexible and suitable for people with poor health issues? Finance, Funding, and Growth The role of financing, particularly in the context of ensuring the sustainability of SEs was a recurrent theme of the seminars. Several interlinked elements emerged around this theme, including the need for investment rather than grant funding, but the distinction between a ‘grant’ and a ‘subsidy’ was also queried (as in why is it OK for Virgin Trains to receive a subsidy but not for a community transport SE to receive a local council grant?). The implications of the funding mix and the impact of grant funding on trading activities of SEs (and vice versa) were seen as important to understand better. Research on growth had largely been around start-up and incubation and not about other stages of development, though one commentator remarked that many social enterprises resembled the structure of family firms. Barriers to growth were not just financial, some SEs are constrained by their environment or locale. There are also ‘reputational’ issues around the concept of social enterprise as a brand. SE needs to be a more recognisable brand and there are opportunities to focus SEs more on concepts of competitiveness in the marketplace. Measurement and Impact Further work on indicators for investment was called for. Measurement was raised as a possible constraint issue for social enterprises and this was related to issues of scale– ie the bigger you are the easier it is to engage with measurement and impact issues such as how to score the ‘added value’ of social enterprise activities. There were calls for the greater use of social audit tools in order to demonstrate SE’a added value, particularly since there is great difficulty assessing intangible benefits, and even suggestions that social audits should become a compulsory requirement. The use of such audits was viewed as important in ensuring that commissioners recognise the social value of SEs. Entrepreneurs and Networks Further work was needed on where social entrepreneurs come from. A specific area was the contrast between ‘heroic’ individuals and more collective forms of entrepreneurship often favoured by women. The gender politics of this was considered important (an example given was where women collectively start enterprises, but as the enterprise grows a man is employed to manage it). Employment status was also highlighted in terms of whether a 'self-employed' status for co-owners of businesses might contribute to an entrepreneurial culture in social enterprises? There was a need to look at social networks of entrepreneurs and enterprises and what value they brought. It was also felt that networks could assist commissioners in knowing what enterprises existed in particular sectors/markets. In terms of governance it was suggested that we need to identify the appropriate solutions for ensuring autonomy and greater democracy within SE – which raised questions about how to measure democracy within an organization, and what the impact of greater democracy in the workplace would have on the sector. Training, Development and Skills Three key points emerged in relation to training and skills: What is the need for tailor-made business support structures The need for inter and intra-sector competency training A recognition that within a community, capacity and skills could be scarce The Research Agenda The research agenda needs to reflect the following: a recognition of Sector (industrial) differences; a focus on country/geographical/ differences; more multi-disciplinary research; a clearer focus on key success factors for SEs and their sustainability and on the barriers to achieving success and sustainability; use of several techniques – longitudinal data and application of innovative methods such as ‘controlled experiments’; greater response and involvement from business schools; making government research more accessible; development of fora for practitioners and academics to meet; Thanks to George Leahy (SEC) and Amanda Williams (ESRC) for compiling these feedback points from the seminars. 1 Peattie, K. and Morley, A. (2008), Social enterprises: Diversity & dynamics, contexts and contributions, Research Monograph, ESRC: Swindon. 2 See for example the Social Enterprise Knowledge Network at http://www.sekn.org/ 3 Geary, J., Marriott, L. and Rowlinson, M. (2004), Journal rankings in business and management and the 2001 Research Assessment Exercise in the UK, British Journal of Management, 15 (2), 95-141 4 Mingers, J. and Harzing, A. (2007) Ranking journals in business and management: a statistical analysis of the Harzing data set, European Journal of Information Systems, 16, 303–316. 5 Desa, G. (2007), Social entrepreneurship: snapshots of a research field in emergence, 3rd International Social Entrepreneurship Research Conference, 18-19 June, Frederiksberg : Denmark 6 ISBE (2007), Response to the ABS academic journal quality guide, Version 1, http://www.isbe.org.uk/pagebuild.php?texttype=ABS_JournalGuide_response 7 Haugh, H. (2006), A research agenda for Social Entrepreneurship?, Social Enterprise Journal, 1 (1), 1-12 8 Nicholls, J. (2007) How can measuring and communicating social value make social inclusion competitive? in Social Enterprise Think Pieces; Outline Proposals. 9-10. SEC 9 Hart, T. and Houghton, G. (2007), Assessing the economic and social impact of social enterprise: feasibility report. Centre for City and Regional Studies, University of Hull. 10 New Economics Foundation. (2003) Social Return on Investment, Miracle or Manacle, www.neweconomics.org 11 Mook, L., Richmond, B.J. and Quarter, J. (2003) Using social accounting to show the value added of cooperatives: The expanded value added statement’, Journal of Co-operative Studies, 35 (3), 183-204. 12 Jones, D., Keogh, B. and O’Leary, H. (2007), Developing the social economy: critical review of the literature, Social Enterprise Institute (SEI) : Edinburgh 13 Bull, M. (2006), Balance: Unlocking performance in social enterprises, Centre for Enterprise: Manchester Metropolitan University Business School. 14 OTS (2006), Social enterprise action plan: Scaling new heights. Office of the Third Sector. 15 OGC (2005), Smaller supplier… better value? The value for money that small firms can offer. Office of Government Commerce / Small Business Service. 16 Hines, F. et al. (2007), The integration of social enterprises into the waste management infrastructure: An assessment, BRASS Research Centre: Cardiff. 17 SEU (2007), Mapping Regional Approaches to Business Support for Social Enterprises, Social Enterprise Unit. 18 Brass (2004), Turning Big Ideas into Viable Social Enterprise, A report for Triodos Bank, Brass Research Centre: Cardiff. 19 Stern, N. et al. (2006), Stern review: The economics of climate change, HM Treasury: London. 20 Porter, M, Van der Linde (1995), Green and competitive – ending the stalemate, Harvard Business Review, pp.120-34. 21 Taylor, J. (2007), Proposal for an ESRC-Supported Programme of Research on Social Enterprise, Social Enterprise Coalition : London. 22 Ravetz, J., Bond, S. and Melkle, A. (2007), One Planet Wales, WWF-UK: Surrey 23 Brown, H. and Murphy, E. (2003), The financing of social enterprises: A special report by the Bank of England, Bank of England Domestic Finance Division: London. 24 Jenkins, H. (2006), Small Business Champions for Corporate Social Responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics, 67 (3), 241-256.