A Brief Introduction to Trinitarian Faith

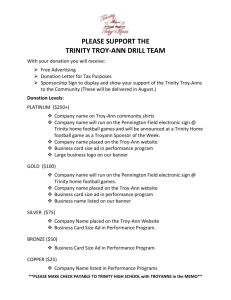

advertisement

www.abortionessay.com A Brief Introduction to Trinitarian Faith Mark A. McNeil Introduction AUTHOR’S NOTE: The following article is intended to express some basic ideas that are involved in understanding Scripture, especially pertaining to the Trinity. Although some space is spent on methodology and interpretive questions, I feel that the diligent reader will profit from carefully considering the points raised. As with all really valuable endeavors, the effort, I think, pays off. For a fairly substantial portion of my Christian experience, I had no significant appreciation of the faith of the Triune God. In fact, for about seven years, I was deeply involved in a religious movement that forcefully denied Trinitarianism. We believed those who held God was a Trinity of persons were guilty not only of idolatrous worship, since they were violating the most basic command to love the one and only God with all of our hearts (Deuteronomy 6:4-6), but also of a flagrant contradiction. It seems ludicrous, we reasoned, to affirm simultaneously that God is both one and three. In light of the fact that Scripture affirms the “oneness” of God, this truth must function as the primary one with which to evaluate and interpret all the rest of the data of revelation.1 Although we accepted the full deity of Christ, there are others who argue in a similar fashion for the radical unity of God, excluding a Trinity of persons, who also reject the claim that Christ is God. There are still others who define Christ’s deity in ways that make Him essentially inferior to the Father. All of these positions, and many others besides, have in common an attack on the Trinity based on claiming its internal inconsistency, inconceivability, or simply its lack of Scriptural support. They all find it necessary, however, to offer some kind of explanation for the various Scriptures that seem to lend themselves to some kind of Trinitarianism. The purpose of this article is to suggest the beginnings of an approach to the Trinity that will primarily consist in some observations regarding our approach to the Sacred text and then some suggestions regarding the nature of revelation itself. This will then lead to a sketch of the biblical data concerning the Trinity. It will then be possible to see first why the Trinity had to develop historically and second why this fact of development does not discredit the doctrine itself but rather tends toward supporting it. Method Much ink has been spilt over “theological methodology” in the recent past. Since this paper has to do with a specific biblical doctrine, or at least one we are claiming to be biblical, it is necessary to begin our comments with some considerations about the nature of biblical interpretation. Since my own study and teaching have revolved around both theology and philosophy, I find it helpful at times to disassociate ourselves from the controversial texts and look at the way we are reasoning. This 1 One primary spokesperson and author of the movement with which I was connected, David K. Bernard, illustrates my point in his book, The Oneness of God. After establishing that “the Old Testament affirms that God is absolutely one in number,” Bernard carries out his analysis of every possible text, he thinks, supporting Trinitarianism in Sacred Scripture with this as the “key.” Concerning such texts as Hebrews 1.2, for example, Bernard writes, “What does creation ‘by the Son’ mean, since the Son did not have a substantial pre-existence before the incarnation?” Or, “We know that the verses of Scripture that speak of creation by the Son cannot mean the Son existed substantially at creation as a person apart from the Father…It is clear that the terms Father, Son, and Holy Ghost cannot imply three separate persons…We must therefore reconcile the plural in (Genesis) 1:26 with the singular of 1:27…Since Genesis 1:26 cannot mean two or more persons in the Godhead…Genesis 1:26 cannot mean a plurality in the Godhead, for that would contradict the rest of Scripture” (115, 117, 134, 148, 49, 51, See also 178, 184, 192, emphasis mine). 3/3/16 1/14 Contact: mmcneil@abortionessay.com www.abortionessay.com “neutral” perspective sometimes makes evident the grounds of disagreement so that, even if we continue disagreeing, we can understand one another more clearly. I have come to see that there are really two approaches to knowledge in philosophy and, to my surprise, I have found it is possible to apply these approaches to the interpretation of Scripture. Philosophical theories about the nature of reality have classically been divided into varying camps under the general categories of analytic and synthetic. These categories are quite helpful in understanding the direction in which the philosopher is carrying out his analysis. We might further clarify these categories by the use of the terms induction and deduction. When one reasons inductively, he is moving from specific facts or observed details and then working towards some general or universal claim. One might examine John, Mary, Susy, and Fred as individual human persons and then begin to “see” some commonalities present. I may notice that each of them have bodies with certain sensory powers. I might also discover that each of them is able to read or carry on a conversation with the others. These facts lead me to the more general claim that each of these “humans” has a rational capacity to engage in activities that go beyond what sense experience alone can disclose. It is quite remarkable that human persons, through the use of the intellect, have a kind of “openness” to all things. Deductive reasoning, on the other hand, attempts to move from general claims or insights to specific conclusions or applications of the claims themselves. I might say that humans are rational creatures and then say that Steve is human and draw from these facts that Steve must also have a rational nature. In any case, I have reasoned from a general truth or truth-claim to a specific application of that truth. Induction, as a kind of reasoning process, is the great tool used in analytic inquiry. We consider the specific facts of human experience and then attempt to consider what must be the case in order for those facts to be experienced. For example, it must be the case that my eyes are instruments or means by which the more basic power of sight operates. Deduction tends to be the basic tool of those using the synthetic approach to knowledge. The overarching, universal, and general truths are used as the key for drawing out more specific truths. The great rationalists like Plato, Descartes, Spinoza, and Leibniz are good examples of this process. Plato had little interest in inductive reasoning based on the facts available to sense experience. Descartes specifically wanted to set up his philosophy on a mathematical basis which, he argued, was based on “intuition” and deduction. One simply “sees” the basic truths and uses those to draw out further implications. The whole Rationalist tradition, however, met with great challenges when it was found that more than one kind of deductive system could be drawn from similar starting-points. The reasoning process used in the deduction was always held in doubt because of the problem of knowing the origin of the intuited starting-truths themselves. The creativity of many genius minds only showed how very difficult it is to have real confidence in a purely deductive theory of reality. Aristotle, on the other hand, made extensive use of the analytic method including the inductive sort of reasoning. He began with the “facts” at hand and worked back towards what must underlie such facts. He would start with the objects of which we have immediate awareness. In my case, I am immediately aware of a computer screen before me including all its colors and shapes. I am also aware of the noises caused by typing and the gentle hum of the computer itself. Looking back at this experience, I can see that I must have organs of sense by which such sense is possible. It is further necessary, as already indicated, to have these organs as channels or instruments through which certain powers or abilities are exercised. These powers, in turn, find their unity in certain functions inside of me and, ultimately, in the intrinsic unifying principle we might call “human nature” or substance. It is important to see that the description is controlled by the data. We will not be justified, on this account, in suggesting that we have certain powers for which there is no corresponding 3/3/16 2/14 Contact: mmcneil@abortionessay.com www.abortionessay.com function or exercised ability. Unlike the rationalist approach, then, we have a “check” on the use of the method in the very data that is used to get at more basic truths. Since our task here is not strictly a philosophical one, we must call a halt to this brief look at philosophical methods and return to the subject of this article. What I would like to suggest is that the real root of my rejection of the Trinity as a young man was the implicit choice of a deductive methodology to the Scriptures evidenced by my adoption of a specific truth as primary and deduced from that truth certain necessary, at least to my mind, consequences. The problem, however, as I came to see more clearly in the course of my studies, was that the data of Scripture was not presented in such a way that it lent itself to this fundamental approach and also that my deduced “truths” were no more “necessary” than were other ways of construing the same data. More specifically, the biblical texts themselves are not written as a deductive philosopher or interpreter would expect. Let it be clear, I am not saying that deduction is a wrong approach altogether. No, inducted truths can be used to generate further conclusions through the process of valid deduction. I don’t find out that there are human animals and brute animals merely by deducing such a fact from the notion of “animal,” however. I come to see that there are a variety of kinds of existing things that fall under the general category of animal through inducted observation. It might be possible after such a procedure to make some deduced conclusions about the things I have learned inductively. If I were doing mathematics, on the other hand, it might be possible to formulate various conclusions merely by reflecting on the meaning of terms, definitions, etc. In our case, however, we are not given in Scripture some series of definitions or propositions with standardized definitions. To the contrary, most of what is known about the subjects of our Faith is gathered from a variety of different literary genres or types. Consider the most foundational section of the Old Testament, the Pentateuch. Here we have several kinds of literature, most dominantly historical narrative and legal prescriptions. Stories or historical descriptions are significantly different from what we might call “systematic theology.” It is because of this lack of “system” in the manner Scripture speaks of God, the human person, sin, etc., we can reconcile texts that apparently seem to contradict. Early in Genesis, God is said to “repent” that He had made man. We find out later, however, that “God is not a man that He should repent.” James writes that in God there is no “shadow of turning,” etc. Malachi depicts God as saying, “I the Lord change not.” Well, there appears to be a significant problem here. Either God changes or He does not, right? Maybe not. If the biblical writers intended the same thing by the uses of “repent,” it would be beyond question that they contradict each other. This is the kind of consistency that you would expect from a deductive philosophical system or from a precise systematic theologian. One would certainly be faulted for setting forth a “system” that involved a good deal of deduction from first principles and definitions only to find that the terms used take on a variety of meanings and significances. If, on the other hand, the biblical writers were not concerned with deductive precision but rather with using language that expressed something meaningful given their task or objective involved in such an expression, we might excuse them for saying things from which we would not be allowed to deduce further claims. That God “repented” of making man is a way of showing God’s displeasure and also the grounds for His subsequent punishment of those giving rise to this displeasure. If we are too strict, however, it will be “deduced” that God “changed His mind” upon “discovering” new data. This, however, is seriously problematic in light of the fact that God appears elsewhere to know all things including the “end from the beginning.” Looking to the other side of the issue, however, it would be equally disastrous to assume that because “God does not change,” that He has no interest or dealings with human beings. It would be awfully narrow to suppose that God is so radically “perfect” and unchanging that He is indistinguishable from a block of ice. The texts regarding “change” in God coupled with those of 3/3/16 3/14 Contact: mmcneil@abortionessay.com www.abortionessay.com immutability, provide a kind of friction that warns us against the deductive methodology since such an approach would assume a univocal or identical meaning between the usage of terms in different settings. Such a procedure would be devastating for understanding Scripture since it would make some texts absurd that really do communicate profound meaning if allowed to speak in the terms and contexts with which they are cloaked. Analogy The renewal of the study of the great thirteenth-century theologian, Thomas Aquinas, at the beginning of this century, gave rise to a fresh look at his theory of religious language normally associated with the term “analogy.”2 This was in large measure due not to the great emphasis on this subject in Aquinas but rather to the pressing challenges in our own age regarding language and the question of how human language could possibly express ideas or realities that seem to transcend the categories available for human expression. Further, given the general attitude of Positivism in the 19th and 20th centuries, whatever was not “seeable” was considered meaningless. Long before, David Hume had offered his own explanation of the origin of ideas such as “God,” heaven, the soul, etc., in terms of their being only confused “ideas” that originated in sense experience. We don’t really have an idea of God in our minds simply because any analysis of the concepts people associate with the term God turn out to be a collection of notions that can be reduced to finite objects of sense experience. We do not have a concept of “infinite,” only “big” with a refusal to set the boundaries. This is far from an actual comprehension or real concept of infinity. In this way, although with a good deal more sophistication and argumentation, Hume and others have argued that “God-talk” is fundamentally meaningless. I remember reading a text by an atheist many years ago in which his “positive” argument against God’s existence was that the idea self-destructs upon examination. Take, for example, God’s “omnipresence.” This means several things in classical theology. For one, it means that God cannot be contained in one place. Further, it does not mean that God is like some kind of transparent “stuff” spread out evenly throughout the universe. No, God is not in a “place” properly speaking. For God to be in a place would mean that He is measurable or less than a real infinite and omnipresent spirit. If, however, God is everywhere but really nowhere, the doctrine becomes absurd. The solution to this dilemma appears whenever we recognize there is a distinction between concepts or mental images formed from sense experience and ideas for which there may be no adequate basis in concepts (e.g. spirits, infinity, etc.). Returning to our problem, for God to be omnipresent, Aquinas argued, means that He is uncontained by any “form.” What limits our presence is the fact that “we” are contained by a limiting essence, God is not. Such a concept is inconceivable, however, for our minds. For this reason, biblical writers seem to discard such notions as omnipresence and talk about God as “coming down” from heaven, etc. In other words, it is not possible to speak of God consistently in the terms that theology develops to attempt at capturing the divine “essence.” The terms do not escape the limitations of human conceptual ability. We are then driven to the rather important conclusion that all human language and conceptualization concerning God is limited and incomplete. God is ever greater than our highest The notion of “analogy” in the context of theology grows from the philosophical concept of the analogy of being (analogia entis). That is, the very way in which things differ is the way in which they are the same. Analogy as a theory of being is grounded in the fact that there is an interconnection and relationship between all things in that they all participate in being but they differ in the precise form of being they take. It is this “sameness in difference” that was used to locate the way in which language about God can be drawn from human experience. Terms are applied to God not with identical sameness of meaning nor with opposite meaning but rather with a mysterious meaning that both captures something of the truth of God while failing to fully or identically capture such truth. 2 3/3/16 4/14 Contact: mmcneil@abortionessay.com www.abortionessay.com thought. This does not mean, however, that the notion of God, since we cannot capture it fully in human concepts, is either absurd or without content. No, I can know that God is infinite or uncaused without fully grasping in concepts what this means. It is not absurd to say that there is a Being Who is uncreated and that is because I can understand what is meant by such a term without fully exhausting or having the power to explain it. Appreciating these various ideas already discussed should lead to a deep sense of humility when approaching the subject of God or, more specifically, the Trinity. Since our concepts are inadequate at grasping fully the divine essence, we should then humbly look at Divine Revelation and consider the concepts used there and then strip away from them everything that is incompatible with the divine nature, i.e., everything that limits God as creatures are limited. This is the standard procedure for dealing with anthropomorphisms, or the application of human characteristics to God. One must first identify the truth that the author intends to communicate and then strip away from the concept everything that is incompatible with the infinity of God. In this way, we can avoid out-right contradictions in Scripture that would result from crass literal interpretation of the text and we may also move towards understanding what the Scriptures intend to communicate about God. This interpretive situation is caused by the nature of the subject we are considering in relationship to the limitations of human language. In sum, we have come to see that Scripture is not in the form necessary for deductive interpretation. Rarely are “definitions” of divine attributes given. Rather, Scripture normally relies on historical narrative and illustrates God’s nature through the activities of God in concrete situations. It is left to the reader, most often, to organize and properly interpret that data. Our task in theology, then, is fundamentally an inductive one in which we gather all the relevant data and allow it to dictate our conclusions. This is admittedly hard work and requires first an intimate knowledge of the texts. From this writer’s perspective, such a situation also requires a profound respect for the earliest interpreters of Sacred Scripture as well as the subsequent history of the Church. This is due to the fact that Scripture can be and has been variously interpreted due to the non-systematic form in which it was given. This shows us that theology is a life-long quest that should be humbly carried out. For those of us who believe the Scriptures to have come from God by inspiration, we believe this depth of the texts only mirrors the infinite depth of our God. It is then irresponsible to reduce the mysterious depth of Scripture to a simplistic “formula” or deductive system. If it turns out that God is three persons and one being, we approach this as a mystery to be believed but not necessarily something that can be reduced to an equation or concept, just as we cannot reduce anything about God to such finite constraints. Notice we are not saying we know nothing about God, only that what we do know about God is limited by our inability to fully grasp such truths and also that we cannot prejudge, based on human categories, what can and cannot be true in God based on human experience. That is not to say that “God” is a collection of contradictions. No, we are compelled to say that there are no real contradictions in God but we must ever beware of the fact that our limited experience may find the transcendent truths of God so unlike our world that we mistakenly see them as contradictory. The Trinity We are now prepared to apply to Scripture the above approach. Perhaps we should state what exactly we mean by the Trinity and then offer its various parts along with some Scriptural basis. In accord with what has been presented above, we will use an inductive approach to gather the data of divine revelation and then we will turn our attention to the deeper problem of understanding the points we have set “gathered.” We will begin with a definition of the term Trinity which will require a bit of discussion concerning the primary terms used in this definition. It is fair to warn the reader that this is 3/3/16 5/14 Contact: mmcneil@abortionessay.com www.abortionessay.com not easy material. I can only say in “apology” that it is worth the effort to attempt understanding what is written. I only wish that more teachers of theology would take the time to learn and explain such matters so that more effort could be spent on illustrations and analogies that would make these profound truths and concepts more meaningful. By the Trinity is classically meant that God is one in His being or essence while internally God is three in person. That is, there are three internal “relations” in God that are most accurately described as “persons.” This definition may not be particularly helpful unless one knows the sense in which the terms “person” and “relation” are intended. The problem is compounded by the shift in meaning that such terms receive through the centuries. Avoiding such controversies, it should be noted that a “person” is, at bare minimum, a rational awareness and consciousness. We do not usually consider dogs “persons” but we do so consider human “persons” in that we all share a selfawareness and awareness of others that enables us to interact with them. It is this idea of interaction that lies at the heart of our distinguishing between persons. I am not you even though we both share human nature. What makes your personhood distinct from my own is precisely all that is yours that is not shared with me. To take a relevant example, a father and son share the same nature but are distinct in two ways: (1) they have distinct interior worlds of consciousness and (2) one stands in a different relationship to the other. The father is the source or origin of the son but in such a way that the son is not identical with the father but is a distinct person related to the father as son. Having at least the beginning of a concept of “person,” we must emphasize the idea of “relation.” For Aquinas, this notion was the key to showing how the Christian understanding of God as Trinity could avoid the charge of Tritheism on the level of reason. Christians do not believe that the persons of the Trinity are separable from each other and therefore cannot say that God is three “substances.” Substance is a loaded theological term with a history that could fill many papers such as this. The term itself literally means “to stand under” and was used in the philosophical tradition to refer to the inner reality of a thing in which its accidental features inhere. The substance is further the source of its properties and accidents (e.g., the substance of “water” gives rise to its wetness). For example, I see a “ball.” You ask me to describe it to you. It is blue, round, hard, etc. No one of these “accidental” features of the ball can be separated from the ball itself so that they are found on their own. For example, one never finds “roundness” just sitting around on its own. No, you always find something that is round. The “something” in view here is the inner principle underlying all accidents and properties and that is classically called the substance. In the case of human persons, we each are, according to Boethius’ ancient definition, an “individual substance of a rational nature.” What unifies my own self as a rational subject is that I am an instance of the human substance. In that sense, then, you and I are distinct instances of the same category of substance (human nature) and are therefore separable. The idea of “relation” is a way in which an individual substance can exist in connection with other things. For example, my father is related to me in a certain way that no other person in this universe is so related. The same may be said of many other relationships in our individual lives. Such relations in our world tend to be “illusory” in that they can quickly cease to exist and they are hard to “see” concretely in the world around us. Think of your relationship with your father. As long as your father is alive, the relationship exists. What happens to the “relation” whenever your father dies? Does it cease to be? Where did it go? This kind of observation has led some to claim that relations are little more than mental entities that have no real existence in the world. This conclusion is unacceptable, however, since it is clear that there is a particular relationship between me and my father that really exists independent of my awareness of it. It is a strange kind of reality, however, in that it is radically dependent on the subjects or substances that are in relationship towards other things. If there were not substantial realities in our world, there would be no possibility of relations (there would not be any distinction between things making relations possible). 3/3/16 6/14 Contact: mmcneil@abortionessay.com www.abortionessay.com The Thomistic contribution to the Trinity, then, was to say that although there is only one “substance” of God, making it forever true that God is radically one, there are three subsistent relations in this one God. In other words, unlike in this world where there is an ontological priority in substances, in God relation has a kind of priority so that the very meaning of the divine persons is found in their relation to each other. Apart from the relations there is no distinction in God. There are three such relations (paternity, filiation, spiration) that are constituted by their very relationship to each other and not by any underlying substantial distinction. This “heavy” thought is worth pondering over and over again. Our greatest problem is conceptualizing how there can be three personal subsisting relations without three corresponding substances. This is the mystery of the Trinity. Persons are constituted not by distinct substances but by distinct relations. The Father begets (paternity), the Son is begotten (filiation), and the Holy Spirit proceeds (spiration). We should now briefly look at the biblical data that lies at the root of this profound mystery. 1. There is one God. It can hardly be argued that Scripture does not affirm this starting-truth. Deuteronomy 6.4 clearly affirms that God is one as do various texts scattered throughout the rest of the Bible. As opposed to the surrounding peoples, the Israelites were to have a single God to Whom their worship was to be directed. 2. This God is known as “Father.” It is quite clear that Jesus’ favorite title for God was “Father.” It is this title or name that is used as the primary one in the model prayer that Christ gave His people to use (Mat. 6:9). Even so, Jesus distinguished between His unique relationship to the Father and that between creatures like ourselves and God (Jn. 20:17). Here is suggested a unique kind of sonship between Jesus and God, His Father. This will be a vital source of reflection on the Trinity as we proceed. 3. This God is known as “Son.” There are many lines of reasoning that have been used to support the conclusion that the Jesus presented in the New Testament understood Himself to be uniquely the “Son of God.” As indicated under number two, we will return to this expression in order to see exactly what it means. It is sufficient here, however, to simply identify Jesus and “Son of God.” That this person is understood to be “God” is a conclusion that may be drawn from the way in which Jesus speaks about the meaning of His relationship to the Father and also from various other indicators. For example, Mark’s Gospel is unique among the Synoptics in that it does not include a great deal of Jesus’ teachings but prefers rather to allow the reader to come to an understanding of Who Jesus was based on recording the actions of Christ. For instance, Jesus displays power over nature in His walking on the water. He displays power over life and death in raising others from the dead and, ultimately, returning to life after His death on the cross. The reader must then decide what these, and other, sorts of miraculous activities suggest. They force the reader to conclude that Jesus was more than a man. In fact, He was the Son of God (Mark 1:1). Additionally, there is also a collection of texts that appear to directly call Jesus God, and these serve as confirmation for our interpretation of the rest of the biblical data (See Jn. 1.1, 20:28). 4. This God is known as “Holy Spirit.” It is quite clear that the Scriptures speak about the Holy Spirit in such a way that we must affirm that He is understood as God (see Acts 5:3-5, Mat. 28:19). There appear to be at least two senses of “Holy Spirit” in the New Testament. One is as a reference to God’s intervention in the course of human history. This use is especially present in Luke’s writings. The frequency with which Luke uses “Holy Spirit” in his work that is evidently quite interested in offering an historically sound rendition of the life of Jesus (Luke 3/3/16 7/14 Contact: mmcneil@abortionessay.com www.abortionessay.com 1:1-4) suggests that he wants us to see history as “guided along” towards its divine end or goal by the work of God’s Spirit or activity in the world. In other texts, however, “Holy Spirit” takes on a more specific sense in distinction from the Father and the Son and it is also in these texts and others that the Holy Spirit is seen as more than divine influence or activity but is none other than God Himself as a personal subject. The Spirit may be “grieved” (Eph. 4:30), lied to (Acts 5:3-5), be “sent” and “testify” (Jn. 14:26) and various other activities that are indicative of personal subjectivity and interaction. 5. The Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are distinct from each other so that they engage in personal interrelationships that force us to affirm that there are personal distinctions or relations within the one true God. The reader should note that we are at this point allowing the data to control our conclusions. There are countless persons who have stopped with the first four points offered above and go to work on developing a view of God’s nature. The movement with which I was associated for a number of years took the first of these points and made the rest fit a definition of “one” in the context of God that did not allow for the Trinity. The Arians, as already mentioned, essentially took the first two points and refused to allow that the Son of God could truly be God with the Father. Our point here is simply that the Father relates to the Son as does the Holy Spirit to the Father and the Son. Clearly the most numerous of such examples would have to be the relationship between the Father and the Son described in the Gospels. Perhaps the most clear of these in the Synoptics would be Matthew 11:27 in which Jesus, referring to Himself in relationship to the Father as “Son,” speaks of a mutual “knowledge” between the Father and the Son. The ability to have knowledge is an indication of personhood and rationality. That each the Father and the Son have such personhood is presupposed by their ability to know and their distinct personhood is indicated by the interaction of knowledge between the persons in their relation of knowledge. John’s Gospel is filled with such examples. In the very first verse the Word, the Son of God (v. 14, 18), is with, or, as the Greek word implies, in relation towards, God and, yet, mysteriously the Word Himself is identified as “God.” Holding that there is only one God, then, we are driven to the conclusion that the one God is interiorily related as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. The same is true of the Holy Spirit since He is “sent” in the name of the Son, “teaches” words Christ taught His disciples, “testifies” of the Son, “proceeds” from the Father, speaks what He “hears,” etc. (John 14:26, 15:26, 16:13). The biblical picture should be taking on some focus at this point. We are confronted with a collection of truths. We are to affirm that there is only one God but we come to find that this God has revealed Himself in a variety of ways. Among these ways of revelation are three in particular which have added significance since they are revealed as standing in relationship not only to us as human beings but in relationship towards each other. This poses a very special problem. The Sabellians, the ancient counterpart to my youthful modalism or belief that God was one person but had performed several “roles” throughout the history of redemption, were quite satisfied with the observation that God had many relations towards us or to the world. That is not so problematic. The problem emerges whenever one takes seriously the interior relations in God Himself. In my conversations with and reading of those who reject the Trinity in favor of some other approach to the biblical material, it is here that opponents will retreat into some deductive system that will refuse to incorporate this kind of data that necessarily forces one to face the question of how the one God can relate within Himself without compromising His unity. Some have been willing to grant an “economic” Trinity or temporary adoption of “roles” by God for our sake. In other words, God appears to be a Trinity but this is really only a temporary situation 3/3/16 8/14 Contact: mmcneil@abortionessay.com www.abortionessay.com that will end whenever the purpose of such roles or distinctions has been fulfilled. This, again, is unsatisfactory for several damaging reasons. First, to say that the economic (temporary) and immanent (eternal) Trinities are not necessarily connected is to deny that we have knowledge of God in time and space that reflects on His eternal state. In other words, the Trinitarian approach admits an economic or temporary manifestation of God in human history but this in turn becomes a “window” into the eternal life of God. To deny that such is the case moves one in the direction of agnosticism concerning what God is eternally since no valid connection can be made or drawn from divine actions in history without some inconsistency or arbitrariness. Second, there is a deeper, but related, problem that surfaces and that is the charge that the Scriptures would be misleading in what they reveal about God if He has chosen to do and say things that do not accurately reflect His inner life. In other words, in order for God to internally relate as He makes Himself known in time, the ontological basis for this kind of reality must be rooted in the eternal nature of God. We would have to seriously question whether or not God is misleading or deceptive if we deny the connection between the two realms (eternal and temporal). Finally, the Scriptural problems continue to emerge. There are various texts in the New Testament that support the claim that the relations between the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit preexist the incarnation as well as the creation of the world. It is such texts as these, in my judgment, that forever forbid a solution to the Trinitarian problem by an appeal to temporary manifestation in contrast to the eternal state of God. (See John 1:1, 17:5, 24, Hebrews 1:1-3.) Special Points We have traveled far in a few short pages. We have examined the difficult question of how we should approach Sacred Scripture given the kind of collection of books that it is. We tried to argue that our approach should be fundamentally an inductive one since this will allow all of Scripture to speak on a matter in the various genres and contexts used and only then should we begin the process of systematizing the data that we have collected. Failure to perform this patient procedure leads to a premature adoption of a principle that in turn is used to “explain away” data that is relevant to the subject that falls outside of that principle. With the subject of the Trinity, we have argued that Scripture supports each of the major aspects of this teaching but the teaching itself presents special problems. These problems arise from our inability to find a sufficient conceptual basis for the teaching. The teaching itself affirms that God is both three and one. God’s oneness is truly one of substance. This unity of substance makes it impossible to conceive of any division or separation in God. We are nonetheless driven by the data to affirm that there are distinctions (not separations) in the divine being but they are not substantial distinctions but relational ones. The divine persons are then constituted by the relations in which they stand towards each other. We call our knowledge and discussion of God analogous because our language and concepts are inadequate to fully and identically describe God. What God has done in time and space, however, as the source of our being and perfections reveals what God is like eternally. We may then legitimately move from the economic Trinity, or the three-fold relationship of God revealed in the context of human salvation, to the immanent Trinity, or what God is like internally throughout eternity. There remain two points that I would like to highlight before concluding this article. The first of these is a more careful look at the crucially important expression, Son of God. The other matter is the practical relevance of the Trinity which can be most clearly seen by reflecting on the nature of love and its meaning as gathered from the New Testament. Son of God. We have suggested at several points that our language about God is analogous or anthropomorphic. These theological terms are different in meaning but they point to a similar fact: 3/3/16 9/14 Contact: mmcneil@abortionessay.com www.abortionessay.com Human language seriously fails to capture the fullness of God’s reality. Analogous language affirms that something of the truth of God is to be found in a limited way in the creation. Although woefully limited and lacking, the perfections of creatures mirror the perfections of the Creator. When a great painter produces a work of art, the work itself is a kind of extension of its author. The link between creature and Creator is the grounds of the affirmation that human language can in fact move towards a true, but limited, expression and contemplation of divine truth. Anthropomorphic language, on the other hand, notes that much of our language about God involves the application of human terminology or physical/mental features to the divine nature. We find numerous references to God’s movements from heaven to earth, the “right hand of God,” the “nostrils” of God, the “eyes” of God, the “feet” of God, etc. Proverbs 15:3, for example, speaks the “eyes of the Lord” that are in “every place beholding the good and the evil.” It would be absurd to take such language in a radically literal way and say that there are eyeballs in every single space of the universe. The fact of the matter is that eyeballs are only instruments of a deeper power or ability, sight. It is through sight that we are able to be present in a particular place and observe what is taking place. For the “eyes of God” to be in “every place,” then, would clearly suggest that the presence of God is everywhere. There is no place where God’s active “sight” and observance is not to be found. A two-fold procedure is involved in understanding this kind of language that pervades our Bible. We must first locate the central truth that is intended in the anthropomorphism. In our example of sight, the central truth is the omnipresence of God. Secondly we must strip away all the limitations found in human instances of sight, or whatever is discovered as the central truth, so that a valid application may be made to the infinite God. The use of the expression, “Son of God,” or, more briefly, “Son,” for Jesus Christ is an expression that must be handled as we do all such uses of human terminology when applied to God. We are clearly in the realm of anthropomorphism since the primary source of information about Father/Son relationships comes from human experience as well as relationships between other kinds of creatures. In accord with our stated procedure, then, we must discover what central ideas are indicated by the use of the terms Father and Son. Several things should come to mind. First, it is clear that if one is truly a “son” of his father, he shares the same nature as his father. Human fathers have human sons. There are no human fathers of dogs or cats or bears. The generation of a son is the generation of a particular kind of being and that “kind” is determined by the nature of the one generating or begetting that son. Second, just as it is true that the son is of the same nature as the father, it is equally true that the son and the father are different precisely because they have distinct “awarenesses” and relationships towards each other. The father is not identical or the same as the son. The father is distinct from the son because the son is a distinct center of awareness having his own “perspective” and, in our case, set of experiences (Although they are very much shaped, in an ideal home, by and with the father.). Third, there is a fundamental equality between the father and son so far as being is concerned. The father is no more a “man” than is the son. One may be more experienced or “manly” than the other but the fundamental nature or reality provides a grounds of equality. This does not mean, however, that there are not relationships of subordination or submission or, unfortunately, of abuse between “men.” We are simply saying that the relationship of father and son indicates equality yet distinction. What this distinction might mean is yet to be seen in our context. Fourth, it must be emphasized that the son receives his nature from his father. In other words, there is a priority of the father to the son inasmuch as the father communicates to the son his nature but the nature that is communicated is fully the same as his own so that the son is equal yet dependent in a sense upon the father as “giver of life” to him. 3/3/16 10/14 Contact: mmcneil@abortionessay.com www.abortionessay.com When we turn to the use of Father/Son terminology in the New Testament, we find many texts that are consistent with the description here given of what these terms mean. John 5:18 states that the Jews sought to kill Christ because He said that “God was His Father, making Himself equal with God.” Clearly the way Jesus was claiming to be related to the Father, God, implied that He was properly the Son of God so it followed that He shared the divine nature. As Son He would share in fundamental equality with God. As we discovered, this is one of the foremost meanings of the expression, “Son of God.” At the same time, John’s Gospel frequently emphasizes a dependence of the Son on the Father that has troubled many. Immediately following the text cited above, Jesus states, “The Son can do nothing of Himself” (John 5:19). This appears to be a denial of equality. Yet again Jesus goes on to state, “That all men might honor the Son, even as they honor the Father.” (v. 23). Apparently turning in the opposite direction again, Jesus states, “For as the Father has life in Himself, so has He given to the Son to have life in Himself” (v. 26). Notice carefully what is happening. Jesus is declaring His dependence on the Father yet at the same time is affirming His fundamental equality with the Father. He can do nothing of Himself, receives life from the Father, etc. He is equal, receives the same honor, has life in Himself. Going back to our brief look at the implications of the Father/Son relationship, we can easily accommodate this kind of language. Sons have equality yet receive their natures and life from their fathers. These two facts are clearly incorporated into Jesus’ teachings here about His own identity. If we have identified the meaning of the Father/Son relationship when applied to Christ and God as indicating an equality of nature yet distinction of persons, one as paternal (Father) and one as filial (Son), our task is not yet complete unless we “strip away” all that is incompatible with talk about God. Clearly what must be stripped away are all elements that limit human relationships temporally or in time. In other words, whatever is true in the divine nature must be so eternally. This follows from the biblical notion of the divine immutability. The relationships of generation in this world come to be since they are relations of temporary creatures who in turn stand in relationships with prior creatures who are causes of their own generation. With God there is no such “chain” of causality. God is self-explanatory and therefore we need go no further than God Himself to find the source and cause of all that He is. If it were asked, “How did Mark McNeil come to be the son of his father?” one may easily reply by giving an account of my parents and all the circumstances involved in my conception and birth. When it is asked how the Son of God came to be the Son of His Father, one humbly replies that such has always been the case and therefore the Father eternally begets the Son and the Son is eternally begotten of His Father. The human instance of generation then fails to fully express the infinite reality of divine paternity and filiation but it nonetheless gives us a “window” into this marvelous truth. In addition to stripping away all time-constraints, we must also strip away all physical limitations. God is Spirit (John 4:24). Remember, anthropomorphic language begins with a truth about God and finds some way in which it is embodied in physical creatures. The physical must be left behind, however, since God, considered in His eternal nature, is not physical but is immaterial or spiritual. We are then speaking here of a generation of the Son and a relationship within God that is of a spiritual nature. This is no doubt why analogies from the mind and thought were not only popular throughout the history of the Church but, apparently, also in John’s thinking (John 1:1). The Father and the Son are then divine persons, equal in nature yet distinct in person. The Son depends on the Father as source of His life and being yet is not thereby diminished in His own deity. He is truly, “God from God, Light from Light, True God from True God. Begotten not made. One in Being with the Father.” This dependence of the Son on the Father does not lead to subordinationism or inequality, as it did in Arianism, simply because we are affirming that the identical nature and reality of the Father is fully communicated to the Son so that an identity of “being” 3/3/16 11/14 Contact: mmcneil@abortionessay.com www.abortionessay.com ( Son and therefore was forced to say that the Son was “made” by the Father sometime in the past. The Trinitarian reply, however, was that the Son was “begotten” by the Father which, in its full meaning, implies a full communication of the divine nature which can only mean that the Son is truly equal with the Father and is therefore eternally related to His Father. The Trinitarian view can accommodate both the dependence and the equality, no other view can. More time would need to be devoted to a similar analysis that can be made of the Holy Spirit. The unique “procession” of the Holy Spirit from the Father and the Son along with analysis of the idea of “spirit,” which in both biblical languages brings to mind “breath” and “wind,” gives rise to the image of the Holy Spirit as the “spiration” or breath of the Father and the Son together. The close identification of the Holy Spirit with the “love” of God also suggests that the Spirit is to be understood as the “bond” or movement of the Father and Son out from themselves in a “shared” love or expression of love that is perfectly present in God as the Third Person of the Trinity. We now turn our attention more specifically to this profound concept of love and its relationship to the Trinitarian faith. Love. It is appropriate that we conclude this look at the Trinity with some comments on the most profound and practical aspect of Trinitarian faith. During my youth, I often heard preachers criticize the Trinity as a matter of faith claiming that it was “impractical” and “didn’t excite anyone.” My pastor claimed that he had never heard a Trinitarian deliver a sermon on the Trinity with any enthusiasm or conviction at all. This was, he claimed, because the doctrine itself was so devoid of meaning and “thrill” that, despite being unbiblical, it was nothing more than a “mind-game” that no one understood and therefore did not contemplate. After years of studying these matters, I can truthfully say that it is the faith of the Triune God that I find most compelling in the Christian faith. I am reminded of Aristotle’s point that the most certain and foundational truths are those that are farthest from our immediate awareness. He was referring, of course, to the most basic principles of reason that are used in all discourse and thought yet rarely reflected upon themselves (if ever). My application is to the faith of the Trinity which underlies all that is uniquely Christian. How is this so? We are told in perhaps the most famous text in all the Bible, “God so loved the world that He gave His only begotten Son…” (John 3:16). We discover later, according to the same writer, that God has given His Son because He is love (1 John 4:8-9). It is remarkable that God is not said to “have” love or “show” love but is rather said to be love. This strong statement suggests that the term love is identified with God in such a way that His being is the essence of love and all other instances of love in this world are instances of the love that is perfected in God. This would have to be true if God is truly love. To the extent that I “have” love, then, I am participating in what is identical with the nature of God. We must be careful here to allow the Scripture to guide us into understanding what “love” means. John 3:16 is a powerful “clue.” The love of God is expressed in a profound “gift,” the gift of Himself. Jesus Himself stated that there is no higher love than that a man lay down his life for his friends (John 15:13). Love’s most perfect expression, then, is found in the gift of one’s self for and toward another. The Scriptures, then, set forth the death of Christ on the cross as, first and foremost, the most profound display of love ever seen in human history. One can conceive of no greater condescension than that the One Who had all power and authority choosing to assume the humble state of a man and then choosing to endure the shame and pain of the Cross (Philippians 2:6-10). We cannot stop with the revelation of divine love in time and space, however, since we are told that, “God is love.” We are led to believe that love is something most perfect in God and that what happened in the Christ-event is an expression of that eternal reality. Christ gives us insight into this reality when He prayed to His Father, “you loved me before the foundation of the world” (John 17:24). Could we expect anything less than this? Is it possible that God could truly be called “love” without 3/3/16 12/14 Contact: mmcneil@abortionessay.com www.abortionessay.com there being internal relations in His nature? No, if love is truly most perfect in the gift of one’s self to another, it follows of necessity that God would have to eternally give Himself internally to Another. It does not work, as some have argued, to say that it is sufficient to say that God “loved” His creation eternally because we would then have to affirm that God is not perfect in Himself but depends on something outside of His nature for His perfections. It is from this flawed reasoning that we find the occasional suggestion that God created “because He was lonely.” This is a far-cry from the God of Scripture. God creates, not to complete Himself, but out of a sheer act of freedom in which, for our benefit, God invites creatures to mysteriously share in His eternal perfection in love (See John 17:2026). If God is three persons, we can see that love is always present in God since the Divine Persons eternally and perfectly give themselves to each other. Only imperfectly is this reflected in human experience but the imperfect examples are the summit of human happiness and fulfillment. It is those who have chosen to give their lives in service to others that are most fulfilled. It is those who have chosen to live selfish lives that are most miserable. It is in dying, then, that we come to live. It is in loving or giving ourselves to another, that we come to find happiness. It is in selfishness that we find the essence of hell. Heaven itself, then, is an invitation for us to enter into the “oneness” of God in love. Conclusion Through much of my Christian experience a great deal of time and energy was expended on apologetics or offering defenses of the Christian faith to those who misunderstand or reject our faith. The most profound arguments or reasons, however, for my continued faith in Jesus Christ are not those that are most easily expressed. To the contrary, the most profound reason for my being a Christian is the Trinity. This is because I find in the faith of the Triune God not only the most sound conclusions based on the Scriptural data but also the most profound vision of human existence known to man. That the God of the universe is fundamentally love, not arbitrary power, is incredible. That the appearance of God in this world was in the form of a lowly “servant” of the world Who gave His life on the Cross, is the most incredible scandal thinkable. At its heart, however, the Christian Gospel affirms what every heart needs and longs for. We need to “die to ourselves.” We need to live by love. We need to come to understand that the reason for being in this universe is that we might share the divine life which is, at its heart, self-giving. You see, the Trinity is not only a dogma of Christian faith, but is a source of the most profound practical truths imaginable. The Trinity has implications for how I treat my family. The Trinity has implications for how I look at all other human beings. The Trinity has implications for the profession that I choose to spend my few days in this world practicing and how that will be done. The Trinity has implications for what I will consider the goal and purpose of my existence. In sum, we have come far and wide to get to this point. It is hoped that those who have endured this “introduction” will be challenged to dig deeper into these truths. The effort is richly rewarding and, I believe, life-changing. www.abortionessay.com ©2000 Mark McNeil 3/3/16 13/14 Contact: mmcneil@abortionessay.com www.abortionessay.com This essay can be copied and used for the glory of God. The following link should appear on web pages and other forms of publication: www.abortionessay.com ©2000 Mark McNeil. Please notify the author of intended use at lbohannon@abortionessay.com. 3/3/16 14/14 Contact: mmcneil@abortionessay.com