Paired Problem Solving [Costs]

advertisement

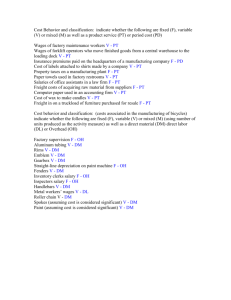

![Paired Problem Solving [Costs]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/008038173_1-a232db278f4ce2465b362708aaa8f91a-768x994.png)

Week 2 Price Taking Firms and Monopolies Firms have little flexibility in setting price; the price is set in the market. Pure price taking firms – a firm that operates in the commodities market, a commodity is an item that has little or no differentiation so no matter who produces it’s the same. Ex. a farmer who raises corn, rice, or pigs; a mining company who mines for gold. EP is price that a price taking firm will always have to settle for. They can produce as much as they want and sell everything they produce, note they can’t affect the market. Marginal Revenue additional revenue you make for every additional item you make. Marginal Cost looks like a check mark because at the beginning they experience economies of scope were producing more is more cost effective but as they make more it becomes more complex and cost moves up. Where cost of producing next unit of output (MC) is equal to what they can sell the next unit for (MR) is the production quantity they would choose. What a firm controls, monopoly or not, is the level of production they choose through marginal cost. Price Price Taking Firm Market Price Marginal Cost Supply (Producers) Price = Demand = Marginal Revenue EP Demand EQ Price Quantity Monopoly Production Quantity Quantity Marginal Cost A monopoly will set price above were MC=MR because they can earn more and there is no one to compete with EP Demand Marginal Revenue Production Quantity Quantity Manufacturing Cost Flows Beg. Inventory Raw Material Purchases $ Raw Materials added End. Inventory Beg. Inventory Direct Labor indirect labor, indirect material, depreciation, misc. $ $ Factory Overhead Work In Process (WIP) End. Inventory Beg. Inventory Finished Goods End. Inventory Include : Raw materials, direct labor, factory overhead Raw materials – The basic material from which a product is made. It is an inventory. o Materials added are purchases. o Materials also added are beginning inventory and ending inventory. Ending inventory carries over to beginning inventory in the next term. o BI+Purchases-BE = Raw materials added to production (WIP) Direct labor - Employees or workers who are directly involved in the production of goods or services. Direct labor costs are assignable to a specific product, cost center, or work order. There is no BI, EI, or inventory coming in. o We just added what workers earn to WIP. Factory overhead - total cost involved in operating all production facilities of a manufacturing business. It’s a catch all for all other types of costs not associated with raw materials or direct labor. o indirect labor (ex. custodians, and supervisors who don’t work directly on the product but are part of manufacturing cost) o indirect cost (ex. oil that goes into the machines that makes product but not the oil doesn’t go directly into the product itself) indirect material (like oil example), depreciation on factory, depreciation on machinery, utilities for the factory, miscellaneous factory overhead. o These costs go into WIP. WIP – products that are being worked on. (inventory account) o Has a BI and EI. o Into it is raw materials, direct labor, and factory overhead costs. o Outflows to finished goods = (BI + 3 costs – BE) Finished Goods – products that are finished and won’t be worked on anymore, ready to ship. (inventory account) o Had a BI and EI o BI + Outflow from WIP - BE Cost of Goods Sold – Keeps track of the costs of goods that were sold. Costs that were accumulated in the finished goods inventory account. o 1st entry – Revenue is a debt to accounts receivable and a credit to sales. (retail number) o 2nd entry – Credit to Finished goods and debt to costs of goods sold. (costs of the retail number) Cost Behavior Within a relevant range, costs can be assumed to be linear. Observations of variable costs suggest that initially firms realize economies of scale on variable costs. So, initially, as volume increases, cost per unit decreases slightly. As volume continues to increase, however, complexity sets in and cost per unit begins to increase. $ VC Q Fixed costs, ultimately, will have to expand in order to accommodate higher volumes. Fixed costs tend to increase in steps. $ FC Q Thus, we assume that costs are linear only within a relatively short, relevant range. Because of this assumption, we can then describe a cost function using the general linear model: Y = α + βX; Where: α = Y-intercept (a poor estimate of Fixed Costs) β = Slope (an good estimate of Variable Cost per Unit) Y = Dependent Variable (Total Costs) X = Independent Variable (Volume/Quantity) Note that because of the shape of the line describing actual costs, the Yintercept (Fixed Cost estimate) can be unstable and dependent on where along the total cost curve we are. In other words, since actual variable costs are geometric in nature, we may be at a point on the curve where the Y-intercept, based on observed levels of cost and quantity, is negative (which it clearly cannot be.) Total Variable Costs (VC) increase with increases in levels of activity. $ Total Fixed Costs (FC) remain constant with increases in levels of activity. $ VC FC Q Mixed costs are actually one cost (e.g., Utilities) that exhibits both a fixed and variable component to total cost. $ Mixed Cost Q Q Total Costs (TC) combine FC and VC (thus their graphical depiction is identical to one of Mixed Cost. $ o s t FC Q Contribution margin (CM) o o o CM = Sales – VC. CM/Unit = Price – VC per Unit. CM% = CM / Sales; or, CM/Unit / Price Contribution margin is the excess of sales over variable costs. Imagine opening a lemonade stand where the cost of the stand itself is $100. If you sell each glass of lemonade for $1 and the cost of each glass of lemonade (sugar, lemons, disposable cup) is $0.25, the contribution margin per glass is $0.75. One can then think about how many glasses of lemonade one must sell in order to cover the fixed costs. Another way of stating it is that for every glass of lemonade sold, $0.75 is contributed toward covering FC (thus toward profit.) This concept becomes critical when we talk about cost/volume/profit analysis. Other common types of costs o Sunk costs These costs have already been incurred and cannot be recovered. They are always irrelevant. o Opportunity costs This is the cost of the next best alternative to a decision. For example, if a manufacturing facility is operating at full capacity, the opportunity cost of producing a special order would be the contribution margin of the product(s) that would be displaced. o Avoidable/Unavoidable costs An avoidable cost would be one that would not be incurred by taking a particular course of action. For the most part, this is another way of identifying variable costs (and alternatively, fixed costs.) o Marginal costs This is the cost that will be incurred if a particular course of action is taken. Normally, we think of this as the cost of producing the next unit; however, we may also think of marginal costs as those incurred at a larger scale (e.g., the marginal cost of accepting an order for 100 units of one of our products; or, perhaps even the cost of building a new factory in Asia.) o Differential costs This concept of costs asks that we identify those costs that are different between two alternatives. In a way, this is an application of Occam’s Razor (The general principal that if all else is equal, the simplest explanation is best.) Sample Questions [Cost Concepts] 1. Badaling Enterprises operates a tour company in Beijing, carrying customers to the Badaling site of the Great Wall. They own several buses and office space downtown. They employ several tour guides, as well as administrative personnel. After one year of operations, and 5,000 trips sold, they have estimated their revenues and costs per trip to be: Price per Trip Variable Costs per Trip Fixed Costs per Trip Net Profit per Trip ¥30 20 __20 (¥10) How many trips will Badaling need to sell to be profitable? A. 5,000 trips B. 10,000 trips C. 13,333 trips D. 15,000 trips E. None of the above. Badaling cannot break even under their present cost structure. Answer: B a. b. c. 2. Multiply FC/Trip by number of trips to calculate total fixed costs (since FC/Trip will only be 20 at this level of activity.) Total FC = 100,000 Contribution margin/Unit = 10 Break-even in units is FC / CM per Unit; or, 100,000/10. A price taking firm (i.e., one competing in a perfectly competitive market) is most likely to adopt which of the following strategies? A. B. C. D. Cost leadership. Differentiation. Monopoly power. Price maximization. Answer: A If you answered “B,” I would be hard pressed to argue with you. The correct answer here, theoretically, is A. Cost management, input mix (how a firm combines Land, Labor and Capital,) cost innovations (e.g., target costing) are each examples of what a firm might do in a perfectly competitive market (where, by definition, the product is homogenous) to increase returns to investors, We all understand, however, that even in very competitive markets, firms spend a lot of money on differentiating their product. 3. Which of the following is the critical question for a firm operating in a perfectly competitive environment? A. B. C. D. What price should I charge? What quantity should I produce? What is my break-even point? How much economic profit do I wish to have? Answer: B In perfectly competitive markets, firms do not get to choose their price; they only get to choose how much of their product to make. The level of production they will choose is that level where Marginal Revenue = Marginal Cost. 4. A sunk cost is A. B. C. D. A cost that is unrecoverable. A form of variable cost. An avoidable cost. A particular type of cost faced by an unsuccessful ship builder. Answer: A …and thus is always irrelevant. 5. Which of the following statements is true? A. B. C. D. Fixed costs per unit remain constant over a relevant range of activity. Total variable costs remain constant over a relevant range of activity. Total fixed costs vary over a relevant range of activity. Variable costs per unit remain constant over a relevant range of activity. Answer: D In the Lille Tissages case, costs are given as “per unit” values. Notice that raw materials per unit, for example, remains constant over all levels of activity shown. If you multiply the level of activity by the cost per unit, you will see why this is a variable cost. Paired Problem Solving Exercise [Analyzing Cost Behavior] Direct Labor Department Insurance Direct Materials General Factory Overhead * Costs per Unit 5,000 Units 6,000 Units 4.00 4.00 3.36 2.80 1.50 1.48 2.00 2.00 7,000 Units 4.00 2.40 1.45 2.00 8,000 Units 4.00 2.10 1.47 2.00 * Allocated at the rate of 50% of Direct Labor. GFO consists largely of plant depreciation and plant support salaries. (The following are one point each.) Identify each of the above costs as most likely being _____ _____ _____ _____ A. B. C. Fixed Cost Variable Cost Mixed Cost 1. 2. 3. 4. Direct Labor Department Insurance Direct Materials General Factory Overhead Answer: Answer: Answer: Answer: B A B A (This last cost is being allocated on the basis of a variable cost. That does not make it a variable cost. Instead, we must look at the description of the cost, which clearly suggests that it is fixed in nature. Note: Fixed costs are costs that don’t change with an increase or decrease in goods or services. They are also expenses that have to be paid by a company, independent of any business activity. While variable costs change with an increase or decrease in goods or services.) The department described above currently sells its product for $10 per unit, generating 6,000 units of sales. The sales manager estimates the following demand function at different price levels: $11.00 per unit 5,000 units sales $9.75 per unit 7,000 units sales $9.40 per unit 8,000 units sales 5. At what price will this department contribute most to firm profitability? A. B. C. D. $11.00 $10.00 $9.75 $9.40 (27,500) (27,120) (30,100) (31,440) * * “D” is the correct answer since it produces the highest contribution margin. ($9,40 $5.47) x 8000 units = $31,440. Incremental Analysis A common aspect of any manager’s job is to make decisions at the margin. Examples include: o Make or buy Basically, this is a decision of whether to buy a raw material, a component to a product we make, or possibly a capital item (e.g., a piece of equipment to be used in production) or make it ourselves. This decision can take a variety of forms. A couple of examples: A consulting firm must decide whether to hire another consulting firm to advise it on a strategy for expanding into a new market or build a team from its own staff to perform the analysis. A software firm must decide whether to purchase a new operating system from a vendor or build its own operating system to its own specifications. A farmer must decide whether to produce his or her own seed inventory or purchase it from a seed company. o Sell or process further Firms routinely manufacture products that are sellable at different points in processing. Firms often face decisions of whether or not to sell a product that is only partially complete. For example, a firm may relieve a “bottleneck” in its production process by selling off excess stock that accumulates at that “bottleneck.” o Sell “as is” or rework When a product is damaged in production, a firm faces a choice of whether to rework the product or sell “as is” at a reduced price. This is a particularly good example of sunk and opportunity costs. The sunk cost is that which has already been incurred. The cost of making the flawed unit is sunk – it cannot be recovered and is therefore irrelevant in the decision. The opportunity cost of reworking the unit is the price at which the damaged product could be sold “as is.” o Accept or reject special orders or bids This is a particularly interesting problem. It involves consideration of opportunity costs in the face of full capacity, marginal costs in the face of excess capacity, long term issues of perhaps attracting a new customer (imagine if you have been approached with your first potential government contract, for example,) signals to existing customers (for example, what would an existing, regular customer think about you selling to a new customer at a lower price?), etc. o Product mix Opportunity costs, obviously play a part in deciding product mix. Resource intensity, however, is also an issue here. While one product may present a higher contribution margin per unit, it may also be more resource intensive (for example, consume excessive time in a machine that is running at full capacity and is needed to produce other products.) Certainly, decisions of managers are not limited to these; however, these decisions offer the opportunity to think about how costs influence our decisions. Managers should make every decision such that it maximizes long term profitability of the firm. Paired Problem Solving [Capacity Issues on a Special Order] Reese Enterprises received an offer to purchase 1000 units of its main product. Reese normally sells this product for $100 per unit. The offer is for $60 per unit. Materials for this product are $15 per unit and are obtained from a local vendor as needed. Direct Labor required to produce each unit is $30 (2 hours @ $15/hour.) The work force at Reese is flexible and can be adjusted easily to meet production needs. Factory Overhead is allocated on the basis of direct labor hours at a cost of $10 per hour. Analysis of overhead costs suggests that variable overhead is related to labor cost and amounts to $0.30 per direct labor dollar. Required: 1. Prepare an analysis of Reese’s decision assuming Reese is currently operating with sufficient excess capacity to meet the requirements of the order. State a conclusion. In the presence of excess capacity, there are no opportunity costs. The most direct way of evaluating this is to calculate the contribution margin per unit. If it is positive, then accept the order. Price Variable costs Raw Materials Direct Labor Variable Factory Overhead Contribution Margin per unit on special order 60 15 30 9 6 54 Increase in firm profits would be $6,000 if the order is accepted. The offer, therefore, should be accepted. 2. If Reese is currently operating at full capacity, what additional information would you need to make this decision? At full capacity, there is an opportunity cost of producing the special order. In this case, it’s an easy calculation, since the variable costs of production appear to be the same (i.e., $54.) Therefore, the opportunity cost is $46 ($100 normal sale price less the variable costs of $54.) A nice presentation of the decision would look like this, perhaps: Price Variable costs Opportunity Cost Raw Materials Direct Labor Variable Factory Overhead Contribution Margin per unit on special order 60 46 15 30 9 (40) 100 Since the contribution margin is negative, the new order should be rejected. And, obviously (I hope) the decision is really very easy. It’s the same thing. If you sell the 1000 units for $60, you can’t sell the very same units for $100. The costs would remain the same, so you would be losing the $40. The only reason I expanded the analysis out is to illustrate how you would proceed if there might be some cost differential (for example, the special order might allow some economies of scale, or the materials might be less expensive than materials for the original units, etc.) Paired Problem Solving [Costs] Anderson Company has produced 500 units of its main product at a total cost of $50,000 (of which 30% is fixed,) but discovers the units are flawed. A local wholesaler offers to buy the units for $30,000. The units normally sell for $120 each. Anderson can rework the units at a variable unit cost of $56, which would make the units marketable at the normal sales price. The allocated fixed cost that would be associated with the rework is $24 per unit. Required: 1. Prepare an analysis of Anderson’s decision. State a conclusion. In order to prepare a numerical analysis of the above situation, one must identify the two alternatives and express the solution in the context of accepting one or the other. The following solution assumes we rework the units: Sales Revenue from Selling the Reworked Units Marginal Costs of Reworking Units: Variable Rework Cost Opportunity Cost of Selling Defective Units Net Benefit (Cost) of Reworking Units $60,000 28,000 30,000 Note that the allocated fixed costs are irrelevant and are thus ignored. 2. Identify any sunk costs in the above situation. Clearly the $50,000 is a sunk cost and irrelevant. 58,000 $2,000 3. Identify any opportunity costs, if any, associated with reworking the units. The opportunity cost of reworking the units is the $30,000 offer from the local wholesaler. Cost/Volume/Profit Analysis – Break-even and Planned Profit Remember: Sales = = Variable Costs Contribution Margin Fixed Costs Profit Important Assumption: Variable Costs as a proportion of Sales remains constant. Equally Important: Fixed Costs as a dollar amount remains constant as Sales increase. Example: If Sales are $100,000, Variable Costs are $75,000 (i.e., 75% of Sales) and Fixed Costs are 40,000; then, if Sales increase to $120,000, Variable Costs will be $90,000 ($120,000 x 75%) and Fixed Costs will remain at $40,000. If CM/unit is the amount contributed toward fixed costs for every unit sold, then Break-even in units = FC / CM per unit. This is the easiest way to think about this. In the above example, if the total number of units originally sold ($100,000) was 50,000 (Price = $2), and variable cost per unit was $1.50; then, Sales would have to be 80,000 units to cover the $40,000 in FC. Contribution Margin per Unit: $2 – $1.50 = $0.50 Break-even in units: $40,000 / $0.50 = 80,000 units (which is $160,000) If CM is always the same proportion of sales (as stated above, and within a relevant range) then in order to break even, CM must equal FC. So, at the break-even point, FC will be the same proportion of sales that CM is. Therefore, Break-even in dollars = FC / CM%, where CM% = CM/Sales. To understand this, look at the equation above. Note that in order to break even (i.e., for profit to be zero) Contribution Margin and Fixed Costs must be equal to one another. Since FC remains constant (in dollars) then, given our example, CM must also be $40,000. Since CM as a percentage of Sales must remain constant, $40,000 must be 25% of Sales. Therefore, $40,000 / 25% = $160,000. (Note that the answer this time is in dollars.) Sales level can be estimated for planned profit by adding planned profit to FC and continuing with the same methods described above (since both fixed costs and planned profit must be “covered” by contribution margin.) Paired Problem Solving [Cost-Volume-Profit Analysis] In 2002, Jameson, Inc. sold 500,000 units of the one product it sells. Selling price per unit was $10. Fixed cost and variable cost per unit at this level of sales was $6 and $2 respectively. Calculate the break-even point for Jameson a. In dollars. Step 1: Calculate total fixed costs at the sales level that is given: 500,000 units x $6/unit = $3,000,000 Step 2: Divide total fixed costs by contribution margin ratio: $3,000,000 / 0.8 = $3,750,000 b. In units. $3,000,000 / $8 Contribution Margin per Unit = 375,000 units. Garner Group had the following results from operations in the first year: Revenues $50,000 Variable Costs 20,000 Gross Margin 30,000 Fixed Costs 40,000 Net Loss $(10,000) Calculate the break-even point in dollars. 30,000/50,000 =0.6 $40,000 / 0.6 = $66,667 1. Badaling Enterprises operates a tour company in Beijing, carrying customers to the Badaling site of the Great Wall. They own several buses and office space downtown. They employ several tour guides, as well as three administrative personnel. After one year of operations, they have estimated their profitability as follows: Revenues ¥100,000 Variable Costs Contribution Margin Fixed Costs Net Profit 40,000 60,000 40,000 ¥20,000 Badaling charges ¥20 per customer per trip. Assuming cost behaviors stay constant, what would be the break-even point for Badaling in ¥? 60,000/100,000 = 0.6 40,000/0.6 = 66,666.666 ¥ 66,667 Customer trips? 66,666.666/20 = 3,333.333 3,334 trips 2. At current levels, Shawn has a contribution margin of 75%. His fixed costs are $15,000 per year. a. If Shawn wishes to earn a net profit of $50,000 per year, what do his revenues need to be? ($15,000 + $50,000) / 0.75 = $86,667 b. If he charges $25 per lawn, how many lawns is that? 3,467 lawns 1. Bryson Enterprises is a publisher. They operate three divisions within one factory: Books, Periodicals, and Special Printings. In December, January and February its Heat and Light Costs for the Books Division were $18,000, $16,000 and $22,000 respectively. Heat and Light Costs are a factory cost and are allocated on the basis of Direct Labor (a variable cost.) Heat and Light are apparently a a. b. c. d. e. 2. Variable Cost Fixed Cost (The cost is allocated on the basis of a variable cost; the description would suggest, however, that it is probably a fixed cost.) Semivariable Cost Chunky Cost Unable to determine without production data. In 2006 McPhee Corp. produced 1000 units of its only product. Fixed costs per unit were $100. Variable costs per unit at the same level were $120. McPhee sells its product for $200 per unit. McPhee’s break even point, in sales dollars, is a. b. c. d. e. 3. $16,667 $25,000 $166,667 $250,000 ($100,000 / 0.4 = $250,000) McPhee can’t break even since its total cost per unit exceeds its price. Bass Inc. had the following operating results in January: Sales $50,000 Variable Costs 20,000 Fixed Costs 20,000 Net Income $10,000 Break even for Bass would appear to be a. b. c. d. 4. $30,000 $33,333 ($20,000 / 0.6 = $33,333) $40,000 Unable to determine from information given. Whether total revenue increases or decreases when price increases depends on a. b. c. d. e. Price elasticity of demand for the product. (Elastic: if price increases revenue decreases. A situation in which the supply and demand for a good or service can vary significantly due to the price. The elasticity of a good or service can vary according to the amount of close substitutes, its relative cost and the amount of time that has elapsed since the price change occurred. Inelastic: if price increases revenue increases. An economic term used to describe the situation in which the supply and demand for a good are unaffected when the price of that good or service changes. Ex. A life saving drug, even if the price dramatically increases demand will still be the same.) Whether costs can be decreased. Whether costs increase at a slower rate. Whether bad debts increase or decrease as price increases. None of the above. In 2005, Kendall, Inc. sold 100,000 units of the one product it sells. Selling price per unit was $7. Fixed cost and variable cost per unit at this level of sales was $8 and $2 respectively. Calculate the break-even point for Jameson a. In dollars. 7-2= 5 $800,000 /( 5/7) = $1,120,000 b. In units. 800,000/(7-2) = 160,000 units Jackson Group had the following results from operations in the first year: Revenues $80,000 Variable Costs $40,000 Fixed Costs $25,000 What revenues will Jackson need to generate in order to produce a profit of$40,000? ($25,000 + $40,000) / 0.5 = $130,000