On the Originality of Literary Works

advertisement

On the Originality of Literary Works This essay aims to discuss three questions. First, what is meant by originality in reference to literary works? Second, where and how is literary originality known to exist? And third, to what extent is originality a valid criterion for the evaluation of literary works? In trying to discuss the first question, we have to admit at the outset that the word originality is capable of quite widely different interpretations in reference to literary works. If we take the word to mean, as the O.E.D. puts it, “the fact or attribute of being primary or first hand,” or “the quality of being independent of and different from anything that has appeared before,” then we may, paradoxically, doubt on one hand that any existing world-famous work has any originality at all, and claim on the other hand that no existing work today is without originality. For on one hand even such earliest known writers as Homer, Pindar, and Anacreon are only “accidental originals,” not real originals; it is only that the works they imitated are lost.1 If we stick to the principle of being “primary or first hand,” the really original writers could very probably be those ancient barbarians who somehow happened to have worked out some prototypes of literary pieces. However, if on the other hand we are willing to be loose about the principle of being “independent of and different from anything that has appeared before,” we should admit that except in the case of a pure plagiarism, no two works are identical just as “no two faces, no two minds, are just alike” (Young 288), and therefore each work is original to a certain degree. To clarify the meaning of originality, we often get inextricably involved in the theory of imitation. As a Romantic preaching the value of original genius, Edward Young has told us that “Imitations are of two kinds; one of nature, one of authors: The first we call originals, and confine the term ‘Imitation’ to the second” (279). This is plainly a refutation to Pope’s neo-classical thought: “Those rules of old discovered, not devised,/ Are nature still, but nature methodized” (ll. 88-89). Indeed, it may seem a peremptory act to a mimetic theorist that one should call the imitation of nature original while calling the imitation of man imitative. But this is the common case we still witness today in the literary circle, though we have not forgot that Plato has suggested that literary works are merely copies of copies. The idea of originality begets another serious problem when we refer it to something from which some other thing or things are derived, rather than to something which is imitated by others. In his “The Origin of the Work of Art,” Martin Heidegger repeatedly asserts that the artist is the origin of the work, that the work is the origin of the artist, and that art is the origin of both artist and work, if by origin is meant “that from and by which something is what it is and as it is” (77 ff.). These assertions of Heidegger’s are all true in their own tight, although we seldom give them any thought when we consider the originality of literary works. There are then many people for whom originality simply means “newness” or “novelty” or “freshness” which the reader feels in a work. This impressionistic interpretation of the word has, of course, its dangers. For one thing, an inexperienced reader or a beginner of reading, for example a first grader, may very probably find an idea or an expression or a technique very original (as it seems to him fresh and new) which in actuality is but commonplace, trite, and disgustingly repetitive. And the other extreme case is, a terribly well-read connoisseur of literature (if there really is such a man) may find very little novelty in a recognized world masterpiece; he may assert with Emerson that “every new writer is only the crater of an old volcano,” or simply agrees that there is nothing new under the sun. Still for some people the word originality may suggest “authenticity” or “genuineness,” as when we are concerned with the originality of Macpherson’s Ossianic poems. In this sense, originality becomes the establishment of true authorship or the prevention from literary forgery or hoax. It is, therefore, the concern of a few textual scholars or editors, not that of the common reader, whose sense of novelty or freshness in a work may not be affected by the fact that the work is a mere fabrication, as the above-mentioned pseudo-Gaetic poems indicate. In connecting originality to the idea of “dissimilarity” or “novelty,” we need to pay attention to a special type of work: namely, parody. As a parody recognizably copies the manner of a known writer or work, it may seem too similar to the “original” to be called “original.” But does it then lack novelty, unprecedentedness, or “originality”? The answer is No. The fact is very paradoxical: a parody is often highly interesting and genuinely original just because it follows so closely the original in so many places. Its originality seems to concur with the fact that it imitates so perfectly! Parody may be an exception or merely a small portion when we discuss literature in the light of originality. But how about such works as said to be “influenced” by other works. It is said that Jacopo Sannazaro’s Arcadia (1504) was indebted chiefly to Boccaccio’s Filocolo and Ninfale d’Ameto for style, diction, and subject matter while it borrowed also from Theocritus, Bion, Moschus, Catullus, Virgil, Ovid, Apuleius, and Petrarch (see Trawick 24). It is also said that the same work of Sannazaro’s had as its direct descendants Guarini’s Faithful Shepherd (Pastor Fido), Montemayor’s Diana, Sidney’s Arcadia, and D’Urfé’s Astrèe while it also influenced Tasso, du Bellay, Spenser, Marlowe, Shakespeare, Phineas Fletcher, Milton, and Keats (see Trawick 25). If these statements are true, can we then call those (Boccaccio, etc.) original who have influenced others and regard those who have been influenced (Guarini, etc.) as lacking originality? The problem of “influence” is very complicated as one work can be influenced by another in countless ways. After reading Shakespeare, for instance, a writer may start writing something very obviously Shakespearean--e.g., with a King Lear plot, or a Hamlet character, or a setting of Midsummer Night’s Dream, or anything reminiscent of Shakespeare’s peculiar dramaturgical device, or just a line allusive to Shakespeare. The same writer, however, may also start writing something non-Shakespearean or even anti-Shakespearean. After reading Macbeth, for example, he may write an Oliver Twist or a To the Lighthouse, showing very little, if any, influence from the great playwright. Or it may chance that having read the lines beginning with “tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow,” the writer suddenly strikes out an idea of writing something temporal and after a long persistent effort finishes a Remembrance of Things Past—an influence certainly from Shakespeare but hardly Shakespearean at all. It follows, therefore, that to say a work is influenced by such and such authors or works is not necessarily equal to saying that it is not original. Those are indeed never original who, as Arthur Schopenhauer says of them, “in order to think at all … need the more direct and powerful stimulus of having other people’s thoughts before them”; who always adopt others’ thoughts as their immediate themes (3). And those of course are also in want of originality who merely adopt others’ techniques or devices idly without using their own brains for “creating” their own works, just as the strong adherents to a certain school or movement of literature often do. Yet, if one receives someone else’s influence within the extent of being “inspired” only, of being able to strike out on one’s own with a mere hint from someone else, one surely may not fall short of originality through that “influence.” So far in trying to define the meaning of literary originality, I have discussed some concomitant difficulties in the job. From this discussion, however, we can conclude temporarily that in reference to literary works originality does not mean real unprecedentedness, nor total uniqueness, nor sheer lack of imitation, nor complete absence of origin, nor absolute newness, novelty and freshness, nor authenticity or genuineness in authorship, nor entire freedom from any influence or affecting source. It means rather the quality that the reader feels existing in a work which seems to him unprecedentedly or uniquely different from anything he has already known to exist in all other works. In giving this definition, I have implicitly touched on the second question of this essay: Where and how is literary originality known to exist? My definition clearly holds that originality as a literary quality certainly exists (or consists if you like) in a literary work. But this objective existence is changed into a subjective existence through the reader’s feeling. That is to say: in order to be known, any literary originality has to be removed from the dead body of the work to the living consciousness of the reader. At this point, one may argue thus: But isn’t it possible, too, that the author (especially the really creative genius) rather than the reader may subjectively foresee the quality of originality in his work to be written, that is, originality can be a pre-existence in the writer’s consciousness to be moved therefrom into the dead body of the work (i.e., the manuscript or the print). To this argument, I concede that the subjective existence of literary originality can be found indeed in both the writer’s consciousness and the reader’s. But as a criterion for judging works, it is only the subjective existence in the reader’s consciousness that counts. In a plainer word, an author may claim (and that truly without any falsehood) that his work is original in such and such a way because he has intended it to be so and he has known no former examples quite like that before. Nevertheless, the writer’s consciousness is never wholly equal to the reader’s consciousness; what is intended often runs short of or in excess of what is extended, to use the two words in a philosophical sense. The originality which looms big in the writer’s own mind may fail to be seen in the reader’s eye. And as evaluation of literary works is normally a job of the reader (especially the special reader called “critic”) rather than the author himself, originality as a judging criterion can naturally be understood as referring only to the subjective existence of that t literary quality in the reader’s consciousness. The discrepancy between the writer’s and the reader’s consciousness of literary originality can be best demonstrated in the well-known case of Edgar Allan Poe’s suspecting Nathaniel Hawthorne of plagiarism. In his Review of Hawthorne’s Twice-Told Tales, Poe once charged Hawthorne with writing in “Howe’s Masquerade” a passage which “resembles a plagiarism [from his ‘William Wilson’] –but in which may be a very flattering coincidence of thought,” not knowing that Hawthorne’s “Howe’s Masquerade” had been first published in the Democratic Review more than a year before his own “William Wilson” appeared.2 Poe’s unfortunate misconception arose, as we know today, quite innocently from his double role as both writer and reader of something claimable of literary originality. As a writer he presumed confidently he was creating something novel and fresh without knowing “a very flattering coincidence of thought” did occur. As a reader he was disgusted with something which was really unoriginal to him at that time but which was truly original to Hawthorne some time earlier. This fact leads us to think of the third question: To what extent is originality a valid criterion for the evaluation of literary works. Since originality as an inherent property of literary works is to be appreciated in the reader’s subjective consciousness, it is subject to the reader’s sensibility to and knowledge of literary works. To give an extreme example, the comparison of a woman to a rose is too stereotyped to claim any originality for most readers today. Yet, to a person who hears the metaphor for the first time, the comparison is as fresh (hence original) as when it was first made in the ancient times. So, theoretically, literary originality is never a stable objective existence. It has a relative quality which changes its value as time and space change with the individual reader. Consequently, a work claimed to be highly original at a particular time in the past might become stale in a future reader’s mind just because similar works have since been repeatedly produced and crammed into the reader’s mind.3 For example, Shakespeare was said to be original for his “tragical harmony,” the harmony of blank verse.4 But after so much blank verse has poured into English drama and other types of literature today, can the present-day reader of Shakespeare feel any trace of originality merely in the great dramatist’s use of blank verse form? Facing this question, one may protest thus: “But it is unfair to efface a former writer’s marks of originality by later writers’ imitation.” True, if we all have a sound historical sense. However, is it obligatory that a reader should have such a sense? Is it necessary or possible that one reads works according to chronological order and has a clear sense about what goes first and what comes next? If the answer is in the negative, what can we do to restrain the individual’s whimsical use of originality as judging criterion for literary works? We allow that there is no absolute originality, that literary originality is a relative matter, and that the degree of originality varies with various readers of various times and places. But, after all, evaluation of literary works is a social behavior. In order to become a valid judging criterion for literary works, originality must be understood as something pertaining not to an individual’s consciousness only, but to the consensus of social class (in reality, the so-called literary circle). Otherwise, literary evaluation on the basis of originality is liable to become a matter of purely personal taste. If originality is limited to the quality communally felt in a work by a literary circle, we still have to admit that what seems original to a particular circle may not prove the same to another circle. It is often asserted, for instance, that we Chinese have no tragedy nor epic of the Greek sort. If this is true, isn’t it also true that a Chinese imitation of Greek tragedy or epic is likely to be found original among the Chinese people while felt to be obviously derivative in the West? Facing a case like this, shall we then widen the judging literary circle to an international one? The answer may be Yes, but then we know it is very hard to find a modern work which is original in any way to people of all times and all places. Accordingly, originality becomes an unworkable criterion for literary evaluation if the judging circle grows too big, just as it does when the judging circle is reduced to a single individual. Therefore, to judge works on the basis of originality, the ideal judging circle should be a moderate size only. And this incidentally betrays the fact that originality as a subjective literary existence cannot be a permanent nor a universal quality. As a judging criterion, originality has another danger. One may easily take what is merely novel for originality. And the easiest way to beget originality in that sense is to frantically break away from all established forms or conventions of literature, leading thus to an overvaluing of the merely odd or eccentric as it does in the case of the Dadaists.5 That originality is not just the prevention of the hackneyed or trite, of the remarkably derivative or the flatly uninspired, has been a stressed point of critics, East and West alike. For instance, Liu Hsieh in our country recognizes the fresh and extraordinary as one of the eight styles of literature, but he observes at the same time: “The literary stutter results from a love of the odd. In chasing after the new and strange, the writer naturally embrangles his throat and lips” (222 & 258). And in his Introduction to Criticism: the Major Texts, Walter Jackson Bate says: “… one can be ‘original’ in any number of ways. For example, to react counter to the truth in every respect is, after all, a form of ‘originality.” (3). Thus, we find it indispensable to hold the pursuit of originality within the bounds of other essential literary principles, e.g., the principle of pleasure or that of unity. In talking about artistic creativity, Vincent Tomas affirms that creativity must be denied where mechanical borrowings are detected, where self-repetition is found, where novelty and freshness are impertinent or bad, and where unity and clarity of artistic objects are lost.6 I think these conditions of denying artistic creativity are also conditions of denying literary originality (here creativity is the synonym of originality). To sum up Tomas’s and any other similar affirmations known to us, we might say that no act of artistic creativity should surpass the ultimate aim of art (the means should forever serve the end); therefore, to be original in any way is to be original in an artistic way, that is, to achieve the final aim of art (be it to delight or to instruct or both). And therefore, in using originality as a judging criterion for literary evaluation, we shall see that what is original in a work is really in keeping with the work as an artistic object, and not just the pursuit of originality for originality’s sake. Aesthetic excellence is seldom the result of going to extremes. Originality in the sense of novelty is for that reason expected to keep a due “aesthetic distance” from tradition. In his “The Sense of the Past,” Lionel Trilling rightly asserts that “the work of any poet exists by reason of its connection with past work, both in continuation and in divergence, and what we call his originality is simply his special relation to tradition” (29). Modern studies of reader response also come to the conclusion that “the right kind or degree of novelty brings pleasant surprise, too little novelty gives boredom, but overmuch novelty is bound to result in frustration and indignation, or even complete wreckage of the reading process.” 7 Indeed, originality should also observe Coleridge’s principle of beauty, namely “unity in multeiry,”8 in order to become a valid judging criterion. So far, I have discussed my proposed three questions, and have, to be sure, left much unsaid. For instance, originality can lie either in a work’s content or its expression. And any discussion of this division will lead to further difficult problems. But as such a discussion need not concern us here, I will be content with quoting a few words from a critic, which can best conclude my points presented herein: Originality … does not necessarily consist in being different from everyone else; it does mean thinking independently of others and making every opinion so much one’s own that it does not matter whether one is the first to hold it or not … The fundamental, the important things are as old as man himself. There are endless permutations and combinations of these prime factors in the problem of life; there are endless new ways in which an old idea may be presented. Herein lies the originality of the artist; if the conception comes with new force and meaning from his pen it is to all intents and purposes original. (Nithie 62-63) Notes 1. This is a point made in Edward Young’s “Conjectures upon Original Composition.” See Paul R. Lieden and Robert Withington, eds., The Art of Literary Criticism (New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts Inc., 1941), p.281. 2. See Note 5 in Sculley Bradley, et al., eds., The American Tradition in Literature, 3rd Edition, Vol. Ⅰ, 1969, p.886. 3. This is a phenomenon to help explicate T. S. Eliot’s truism in his “Tradition and the Individual Talent”: “… the past should be altered by the present as much as the present is directed by the past.” 4. Samuel Johnson doubts this claim of Dennis’s in his “Preface to Shakespeare.” 5. This is a point made in M. K. Danziger & W. S. Johnson, An Introduction to Literary Criticism (1966), p.174. 6. I derive these points of Tomas’s from the Liu Shih-Tsao’s Chinese translation in Liu Shou-yi, ed. Critical Essays on Western Literature (Taipei: Lian-Ching Publishing Co., 1977), pp. 99-116. Tomas’s original is published in Philosophical Review (1958, January), Vol. Ⅳ, No. 2. 7. See Chi Ch’iu-lang, “Liu Hsieh’s View on Novelty and Russian Formalists’ Concept of Defamiliarizaton,” Tamkang Review (1980, Spring & Summer), Vol. Ⅹ, Nos. 3 & 4, p. 508. Chi’s statement is based on the study of Liu Hsieh, Wolfgang Iser, and some Russian Formalists in regard to their conception of novelty which has much to do with our present topic. 8. For this point, see Coleridge’s Biographia Literaira, Ⅱ. , and also his On the Principles of Genial Criticism, Essay Ⅲ. Works Consulted Adams, Hazard, ed. Critical Theory since Plato. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1971. Bate, Walter Jackson, ed. Criticism: the Major Texts. Enlarged ed. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1970. Bradley, Sculley, et al., eds. The American Tradition in Literature. 3r ed. Vol. I, 1969. ? Chi, Ch’iu-lang. “Liu Hsieh’s View on Novelty and Russian Formalists’ Concept of Defamiliarization.” Tamkang Review (1980, Spring & Summer), Vol. X, Nos. 3 & 4. Coleridge, S. T. Biographia Literaria. --------. On the Principles of Genial Criticism, Essay III, rpt. in Adams, 463-7. Danziger M. K. & W. S. Johnson. An Introduction to Literary Criticism. New York: D. C. Heath, 1961. Eliot, T. S. “Tradition and the Individual Talent,” rpt. in Adams, 784-7. Heidegger, Martin. Poetry, Language, Thought. Translated by Albert Hofstadter. New York: Harper & Row, 1971. Johnson, Samuel. “Preface” to Shakespeare, rpt. in Adams, 329-336. Liu, Hsieh. The Literary Mind and the Carving of Dragon. Translated by Vincent Yu-chung Shih. Taipei: Chung Hua Book Co., 1970. Liu, Show-yi, ed. Critical Essays on Western Literature. Taipei: Lian-Ching Publishing Co., 1977. Nithie, Elizabeth. The Criticism of Literature. New York: Macmillan, 1928. Pope, Alexander. An Essay on Criticism, rpt. in Adams, 278-86. Schopenhauer, Arthur. The Art of Literature. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P, 1960. Trawick, Buckner B. World Literataure. Vol. II. New York: Barnes & Noble, 1955. Trilling, Lionel. “The Sense of the Past.” Essays in Modern Literary Criticism. Ed. Ray B. West. New York: Rinehart, 1960. Young, Edward. “Conjectures on Original Composition.” The Art of Literary Criticism. Ed. Paul R. Lieden & Robert Withington. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1941.

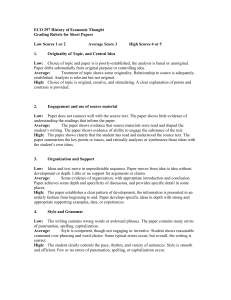

![Introduction [max 1 pg]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/006997862_1-296d918cc45a340197a9fc289a260d45-300x300.png)