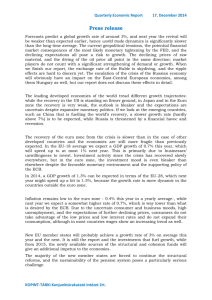

Macroeconomic Forecast - July 2009

advertisement