___________________________________________________________________

Life in America

BREAKUP OF THE FAMILY

Can we reverse the trend?

“What is needed is anew social movement that stresses a lasting,

monogamous, heterosexual relationship which includes the procreation of

children”

By David Popenoe

1

2

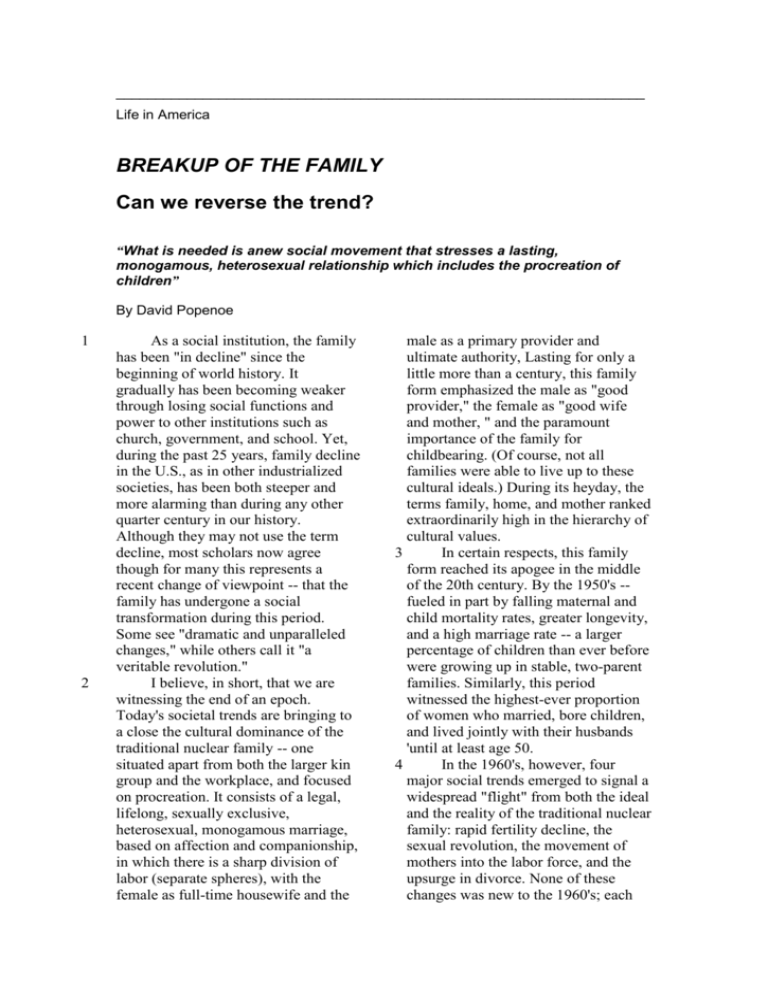

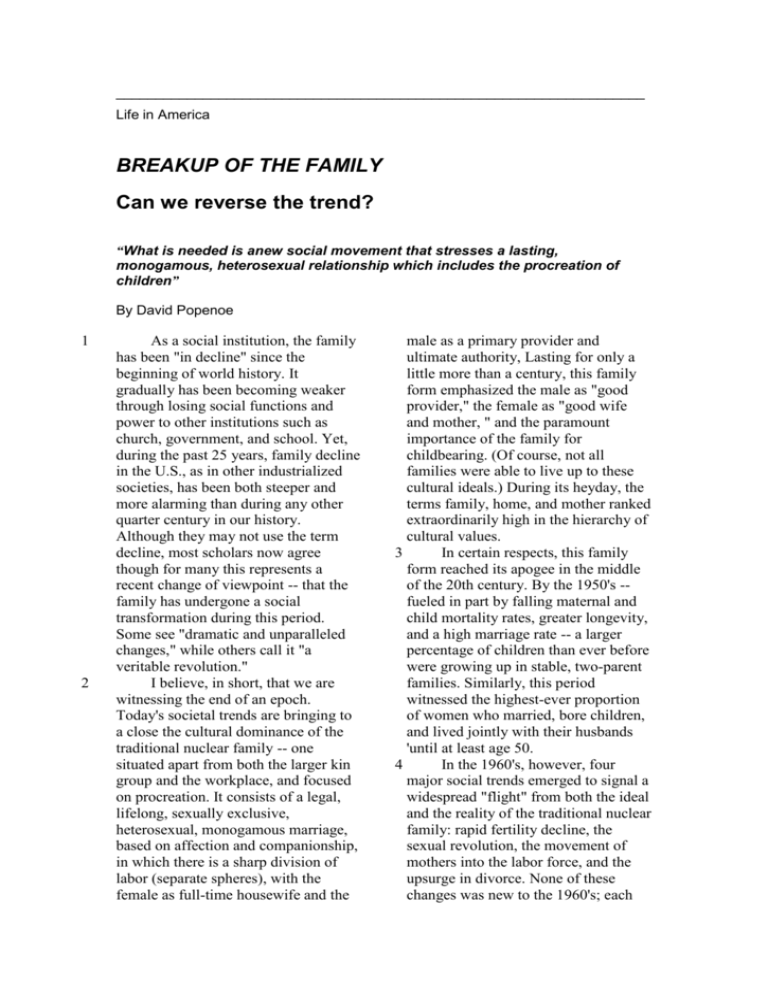

As a social institution, the family

has been "in decline" since the

beginning of world history. It

gradually has been becoming weaker

through losing social functions and

power to other institutions such as

church, government, and school. Yet,

during the past 25 years, family decline

in the U.S., as in other industrialized

societies, has been both steeper and

more alarming than during any other

quarter century in our history.

Although they may not use the term

decline, most scholars now agree

though for many this represents a

recent change of viewpoint -- that the

family has undergone a social

transformation during this period.

Some see "dramatic and unparalleled

changes," while others call it "a

veritable revolution."

I believe, in short, that we are

witnessing the end of an epoch.

Today's societal trends are bringing to

a close the cultural dominance of the

traditional nuclear family -- one

situated apart from both the larger kin

group and the workplace, and focused

on procreation. It consists of a legal,

lifelong, sexually exclusive,

heterosexual, monogamous marriage,

based on affection and companionship,

in which there is a sharp division of

labor (separate spheres), with the

female as full-time housewife and the

male as a primary provider and

ultimate authority, Lasting for only a

little more than a century, this family

form emphasized the male as "good

provider," the female as "good wife

and mother, " and the paramount

importance of the family for

childbearing. (Of course, not all

families were able to live up to these

cultural ideals.) During its heyday, the

terms family, home, and mother ranked

extraordinarily high in the hierarchy of

cultural values.

3

In certain respects, this family

form reached its apogee in the middle

of the 20th century. By the 1950's -fueled in part by falling maternal and

child mortality rates, greater longevity,

and a high marriage rate -- a larger

percentage of children than ever before

were growing up in stable, two-parent

families. Similarly, this period

witnessed the highest-ever proportion

of women who married, bore children,

and lived jointly with their husbands

'until at least age 50.

4

In the 1960's, however, four

major social trends emerged to signal a

widespread "flight" from both the ideal

and the reality of the traditional nuclear

family: rapid fertility decline, the

sexual revolution, the movement of

mothers into the labor force, and the

upsurge in divorce. None of these

changes was new to the 1960's; each

represents a tendency that already was

in evidence in earlier years. What

happened in the 1950's was a striking

acceleration of the trends, made more

dramatic by the fact that, during the

1960's they had leveled off and, in

some cases, even reversed direction.

5

First, fertility declined in the U.S.

by almost 50% between 1960 and

1989, from an average of 3 children

per woman to only 1.9. Although

births have been diminishing gradually

for several centuries (the main

exception being the two decades

following World War II), the level of

fertility during the past decade was the

lowest in U.S. history and below that

necessary for the replacement of the

population.

6

A growing dissatisfaction with

parenthood is now evident among

adults in our culture, along with a

dramatic decrease in the stigma

associated with childlessness. Some

demographers predict that 20-25% of

today's young women will remain

completely childless, and nearly 50%

will be either childless or have only

one offspring.

7

Second, the sexual revolution has

shattered the association of sex and

reproduction, The erotic has become a

necessary ingredient of personal wellbeing and fulfillment, both in and

outside of marriage, as well as a highly

remarkable commodity. The greatest

change has been in the area of

premarital sex. From 1971 to 1982

alone, the proportion of unmarried

females in the U.S, aged 15-19 who

engaged in premarital sexual

intercourse jumped up from 28 to 44%.

This behavior reflects a widespread

change in values; in 1967, 85% of

Americans condemned premarital sex

as morally wrong, compared to 37% in

1979.

8

The sexual revolution has been a

major contributor to the striking

increase in unwed parenthood.

Nonmarital births jumped from five

percent of all births in 1960 (22% of

black births) to 22% in 1985 (9,0% of

black births). This is the highest rate of

nonmarital births ever recorded in the

U. S.

9

Third, although unmarried

women long have been in the labor

force, the past quarter century have

witnessed a striking movement into the

paid work world of married women

with children. In 1960, only 1 9% of

married women with children under

the age of six were in the labor force

(39% with children between 6 and 17);

by 1986, this figure had climbed to

54% (68% of those with older

children).

10

Fourth, the divorce rate In the

U.S. over the past 25 years (as

measured by the number of divorced

persons per 1,000 married persons) has

practically quadrupled, going from 35

to 130. This has led many to refer to a

divorce revolution. The probability that

a marriage contracted today will end in

divorce ranges from 44 to 66%,

depending upon the method of

calculation.

11

These trends signal a widespread

retreat from the traditional nuclear

family in its dimensions of a lifelong,

sexually exclusive unit, focused on

children, with a division of labor

between husband and wife. Unlike

most previous changes, which reduced

family functions and diminished the

importance of the kin group, that of the

past 25 years has tended to break up

the nucleus of the family unit -the bond

between husband and wife. Nuclear

units, therefore, are losing ground to

single- parent households, serial and

step- families, and unmarried and

homosexual couples.

12

The number of single-parent

families, for example, has grown

sharply -the result not only of marital

breakup, but also of marriage decline

(fewer persons who bear children are

13

14

getting married) and widespread male

abandonment. In 1960, only nine

percent of U.S. children under 18 were

living with a lone parent; by 1986, this

figure had climbed to nearly onequarter of all children. (The

comparable figures for blacks are 22

and 53%.) Of children born during

1950-54, only 19% of whites (48% of

blacks) had lived in a single-parent

household by the time they reached age

17. For children born in 1990,

however, the figure is projected to be

70% (94% for blacks).

The psychological character of

the marital relationship also has

changed substantially over the years.

Traditionally, marriage has been

understood as a social obligation -- an

institution designed mainly for

economic security and procreation.

Today, marriage is understood mainly

as a path toward self-fulfillment. One's

self development is seen to require a

significant other, and marital partners

are picked primarily to be personal

companions. Put another way,

marriage is becoming

deinstitutionalized. No longer

comprising a set of norms and social

obligations that are enforced widely,

marriage today is a voluntary

relationship that individuals can make

and break at will. As one indicator of

this shift, laws regulating marriage and

divorce have become increasingly

more lax.

As psychological expectations

for marriage grow ever higher, dashed

expectations for personal fulfillment

fuel our society's high divorce rate.

Divorce also feeds upon itself: With

more divorce, the more "normal" it

becomes, with fewer negative

sanctions to oppose it and more

potential partners available. In general,

psychological need, in and of itself, has

proved to be a weak basis for stable

marriage.

15

Trends such as these have

dramatically reshaped people's

longtime connectedness to the

institution of the family. Broadly

speaking, the institution of the family

has weakened substantially over the

past quarter-century in a number of

respects. Individual members have

become more autonomous and less

bound by the group, and the latter has

become less cohesive. Fewer of its

traditional social functions are now

carried out by the family; these have

shifted to other institutions. The family

has grown smaller in size, less stable,

and with a shorter life span; people are,

therefore, family members for a

smaller percentage of their lives. The

proportion of an average person's

adulthood spent with spouse and

children was 62% in 1960, the highest

in our history. Today, it has dropped to

a low of 43%.

16

The outcome of these trends is

that people have become less willing to

invest time, money, and energy in

family life. It is the individual, not the

family unit, in whom the main

investments increasingly are made.

17

These trends are all evident, in

varying degrees, in every industrialized

Western society. This suggests that

their source lies not in particular

political or economic systems, but in a

broad cultural shift that has

accompanied industrialization and

urbanization. In these societies, there

clearly has emerged an ethos of radical

individualism in which personal

autonomy, individual rights, and social

equality have gained supremacy as

cultural ideals. In keeping with these

ideals, the main goals of personal

behavior have shifted from

commitment to social units of all kinds

(families, communities, religions,

nations) to personal choices, lifestyle

options, self-fulfillment, and personal

pleasure.

Social consequences

18

19

20

How are we to evaluate the social

consequences of recent family decline?

Certainly, one should not jump

immediately to the conclusion that it is

necessarily bad for our society. A great

many positive aspects to the recent

changes stand out as noteworthy.

During this same quarter-century,

women and many minorities clearly

have improved their status and

probably the overall quality of their

lives. Much of women's status gain has

come through their release from family

duties and increased participation in

the labor force. In addition, given the

great emphasis on psychological

criteria for choosing and keeping

marriage partners, it can be argued

persuasively that those marriages today

which do endure are more likely than

ever before to be true companionships

that are emotionally rewarding.

This period also has seen

improved health care and longevity, as

well as widespread economic affluence

that has produced, for most people, a

material standard of living that is

historically unprecedented. Some of

this improvement is due to the fact that

people no longer are dependent on

their families for health care and

economic support or imprisoned by

social class and family obligation.

When in need, they can now rely more

on public care and support, as well as

self-initiative and self- development.

Despite these positive aspects,

the negative consequences of family

decline are real and profound. The

greatest negative effect of recent

trends, in theopinion of nearly

everyone, is on children. Because they

represent the future of a society, any

negative consequences for them are

especially significant. There is

substantial, if not conclusive, evidence

that, partly due to family changes, the

quality of life for children in the past

25 years has worsened. Much of the

problem is of a psychological nature,

and thus difficult to measure

quantitatively.

21

Perhaps the most serious problem

is a weakening of the fundamental

assumption that children are to be

loved and valued at the highest level of

priority. The general disinvestment in

family life that has occur- red has

commonly meant a disinvestment in

children's welfare. Some refer to this as

a national "parent deficit." Yet, the

deficit goes well beyond parents to

encompass an increasingly less childfriendly society.

22

The parent deficit is blamed all

too easily on newly working women.

Yet, it is men who have left the

parenting scene in large numbers.

More than ever before, fathers are

denying paternity, avoiding their

parental obligations, and absent from

home. (At the same time, there has

been a slow, but not offsetting, growth

of the "house- father" role.)

23

The breakup of the nuclear unit

has been the focus of much concern.

Virtually every child desires two

biological parents for life, and

substantial evidence exists that childrearing is more successful when it

involves two parents, both of whom

are strongly motivated to the task. This

is not to say that other family forms

cannot be successful, only that, as a

group, they are not as likely to be so.

This also is not to claim that the two

strongly motivated parents must be

organized in the patriarchal and

separate-sphere terms of the traditional

nuclear family.

24

Regardless of family form, there

has been a significant change over the

past quarter-century in what can be

called the social ecology of childhood.

Advanced societies are moving ever

further from what many hold to be a

highly desirable child-rearing

environment, one consisting of a

relatively large family that does a lot of

things together, has many routines and

traditions and provides a great deal of

quality contact time between adults

and children; regular contact with

relatives, active neighboring in a

supportive neighborhood, and contact

with the adult world of work; little

concern on the part of children that

their parents will break up; and the

coming together of all these

ingredients in the development of a

rich family subculture that has lasting

meaning and strongly promulgates

such values as cooperation and sharing.

Agendas for change

25

26

27

What should be done to

counteract or remedy the negative

effects of family decline? This is the

most controversial question of all, and

the most difficult to answer. Among

the agendas for change that have been

put forth, two extremes stand out as

particularly prominent in the national

debate. The first is a return to the

structure of the traditional nuclear

family characteristic of the 1950's; the

second is the development of extensive

governmental policies.

Aside from the fact that it

probably is impossible to return to a

situation of an earlier time, the first

alternative has major drawbacks. It

would require many women to leave

the workforce and, to some extent,

become "de-liberated," an unlikely

occurrence indeed. Economic

conditions necessitate that even more

women take jobs, and cultural

conditions stress ever greater equality

between the sexes.

In addition to such

considerations, the traditional nuclear

family form, in today's world, may be

fundamentally flawed. As an indication

of this, one should realize that the

young people who led the

transformation of the family during the

1960's and 1970's were brought up in

1950's households. If the 1950's

families were so wonderful, why didn't

their children seek to emulate them? In

hindsight, the 1950's seem to have

been beset with problems that went

well beyond patriarchy and separate

spheres. For many families, the

mother-child unit has become

increasingly isolated from the kin

group, the neighborhood and

community, and even from the father,

who worked a long distance away.

This was especially true for women

who were fully educated and eager to

take their place in work and public life.

Maternal childrearing under these

historically unprecedented

circumstances became highly

problematic.

28

Despite such difficulties, the

traditional nuclear family is still the

one of choice for millions of

Americans. They are comfortable with

it, and for them it seems to work. It is

reasonable, therefore, at least not to

place roadblocks in the way of couples

with children who wish to conduct

their lives according to the traditional

family's dictates. Women who freely

desire to spend much of their lives as

mothers and housewives, outside of the

labor force, should not be penalized

economically by public policy for

making that choice. Nor should they be

denigrated by our culture as secondclass citizens.

29

The second major proposal for

change that has been stressed in

national debate is the development of

extensive governmental programs

offering monetary support and social

services for families, especially the

new "non-nuclear" ones. In some

cases, these programs assist with

functions these families are unable to

perform adequately; in others, the

functions are taken over, transforming

them from family to public

responsibilities. This is the path

30

31

followed by the European welfare

states, but it has been less accepted by

the U.S. than by any other

industrialized nation. The European

welfare states have been far more

successful than the U.S. in minimizing

the negative economic impact of

family decline, especially on children.

In addition, many European nations

have established policies making it

much easier for women (and

increasingly men) to combine work

with childrearing. With these successes

in mind, it seems inevitable that the

U.S. will (and I believe should) move

gradually in the European direction

with respect to family policies, just as

we are now moving gradually in that

direction with respect to medical care.

There are clear drawbacks,

however, in moving too far down this

road. If children are to be served best,

we should seek to make the family

stronger, not to replace it. At the same

time that welfare states are minimizing

some of the consequences of decline,

they also may be causing further

breakup of the family unit. This

phenomenon can be witnessed today in

Sweden, where the institution of the

family probably has grown weaker

than anywhere else in the world. On a

lesser scale, it has been seen in the

U.S. in connection with our welfare

programs. Fundamental to successful

welfare state programs, therefore, is

keeping uppermost in mind that the

ultimate goal is to strengthen families.

While each of the above

alternatives has some merit, I suggest a

third one. It is premised on the fact that

we cannot return to the 1950's family,

nor can we depend on the welfare state

for a solution. Instead, we should strike

at the heart of the cultural shift that has

occurred, point up its negative aspects,

and seek to reinvigorate the cultural

ideals of family, parents and children

within the changed circumstances of

our time. We should stress that the

individualistic ethos has gone too far,

that children are getting woefully

short-changed, and that, over the long

run, strong families represent the best

path toward self-fulfillment and

personal happiness. We should bring

again to the cultural forefront the old

ideal of parents living together and

sharing responsibility for their children

and each other.

32

What is needed is a new social

movement whose purpose is the

promotion of families and their value

within the new constraints of modern

life. It should point out the supreme

importance to society of strong

families, while at the same time

suggesting ways they can adapt better

to the modern conditions of

individualism, equality, and the labor

force participation of both women and

men. Such a movement could build on

the fact that the overwhelming

majority of young people today still

put forth as their major life goal a

lasting, monogamous, heterosexual

relationship which includes the

procreation of children. It is reasonable

to suppose that this goal is so pervasive

because it is based on a deep-seated

human need.

33

The time seems right to reassert

that strong families concerned with the

needs of children are not only possible,

but necessary.