Humour Rules

advertisement

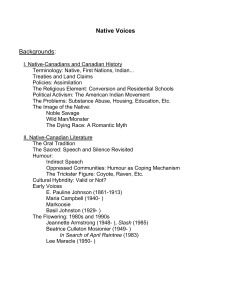

Humour Rules The heading can be read both in the straightfOrward (прямой ) sense of 'rules about humour' and in the graffiti sense of 'humour rules, OK!'*) The latter is in fact more appropriate (подходящий), as the most nOticeable (примечательный) and important 'rule' about humour in English conversation is its dominance and pervasiveness (распространенность). Humour rules. Humour governs. Humour is omniprEsent and omnipOtent. I wasn't even going to do a separate chapter on humour, because I knew that, like class, it pErmeates (просачиваться) every aspect of English life and culture, and would therefore just naturally crop up (возникать) in different contexts throughout the book. It did, but the trouble with English humour is that it is so pervasive (вездесущий) that to convey its role in our lives I would have to mention it in every other paragraph, which would eventually become tedious (нудный, утомительный) - so it got its own chapter after all. There is an awful lot of guff (чушь) talked about the English Sense of Humour, including many patriotic attempts to prove that our sense of humour is somehow unique and superior to everyone else's. Many English people seem to believe that we have some sort of global monopoly, if not on humour itself, then at least on certain 'brands' of humour - the high-class ones such as wit (остроумие) and especially irony. My findings indicate that while there may indeed be something distinctive about English humour, the real 'defining characteristic' is the vAlue (ценность, значение) we put on humour, the central importance of humour in English culture and social interactions. In other cultures, there is 'a time and a place' for humour; it is a special, separate kind of talk. In English conversation, there is always an undercUrrent (скрытая тенденция, букв. глубинное течение) of humour. We can barely manage to say 'hello' or comment on the weather without somehow contriving (умудряться, ухитряться) to make a bit of a joke out of it, and most English conversations will involve at least some degree of bAnter (добродушное подшучивание), teasing (поддразнивать), irony, understAtement (подтекст, недоговорка, замалчивание), humorous self-deprecAtion (осуждение), mockery (насмешка) or just silliness. Humour is our 'default mode', if you like: we do not have to switch it on deliberately, and we cannot switch it off. For the English, the rules of humour are the cultural equivalent of natural laws — we obey them automatically, rather in the way that we obey the law of gravity. THE IMPORTANCE OF NOT BEING EARNEST RULE At the most basic level, an underlying rule in all English conversation is the proscription (запрет, изгнание, опала) of 'earnestness'. Although we may not have a monopoly on humour, or even on irony, the English are probably more acUtely (сильно) sensitive than any other nation to the distinction between 'serious' and 'sOlemn' (торжественный), between 'sincErity' (искренность) and 'Earnestness' (честность). This distinction is crucial to any kind of understanding of Englishness. I cannot emphasize this strongly enough: if you are not able to grasp these subtle but vital (жизненно важный) differences, you will never understand the English — and even if you speak the language fluently, you will never feel or appear entirely at home in conversation with the English. Your English may be impEccable (безупречный), but your behavioural 'grammar' will be full of glaring (бросающихся в глаза) errors. Once you have become suffIciently (достаточно) sensitized to these distinctions, the Importance of Not Being Earnest rule is really quite simple. Seriousness is acceptable, solemnity is prohibited. Sincerity is allowed, earnestness is strictly forbidden. Pomposity (напыщенность, важность) and self-importance are outlawed (вне закона). Serious matters can be spoken of seriously, but one must never take oneself too seriously. The ability to laugh at ourselves, although it may be rooted in a form of arrogance (неведение), is one of the more endearing (привлекательный) characteristics of the English. (At least, I hope I am right about this: if I have overestimated our ability to laugh at ourselves, this book will be rather unpopular.) To take a deliberately extreme example, the kind of hand-on-heart, gushing earnestness and pompous, Bible-thumping solemnity favoured by almost all American politicians would never win a single vote in this country — we watch these speeches on our news programmes with a kind of smugly detached amusement, wondering how the cheering crowds can possibly be so credulous as to fall for this sort of nonsense. When we are not feeling smugly amused, we are cringing with vicarious embarrassment: how can these politicians bring themselves to utter such shamefully earnest platitudes, in such ludicrously solemn tones? We expect politicians to speak largely in platitudes, of course — ours are no different in this respect — it is the earnestness that makes us wince. The same goes for the gushy, tearful acceptance speeches of American actors at the Oscars and other awards ceremonies, to which English television viewers across the country all respond with the same finger-down-throat 'I'm going to be sick' gesture. You will rarely see English Oscar-winners indulging in these heart-on-sleeve displays — their speeches tend to be either short and dignified or self-deprecatingly humorous, and even so they nearly always manage to look uncomfortable and embarrassed. Any English thespian who dares to break these unwritten rules is ridiculed and dismissed as a 'luvvie'. And Americans, although among the easiest to scoff at, are by no means the only targets of our cynical censure. The sentimental patriotism of leaders and the portentous earnestness of writers, artists, actors, musicians, pundits and other public figures of all nations are treated with equal derision and disdain by the English, who can spot the slightest hint of self-importance at twenty paces, even on a grainy television picture and in a language we don't understand. Kate Fox, Watching the English, The Hidden Rules of English Behaviour, 2004, London, pp. 61 – 63