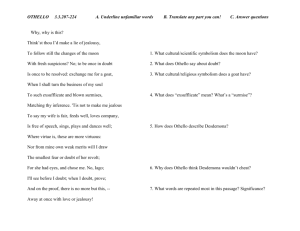

Cook 1 Megan Cook Susan Chambers ENC 3334 13 July 2012

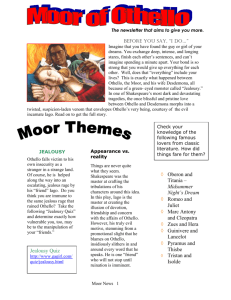

advertisement

Cook 1 Megan Cook Susan Chambers ENC 3334 13 July 2012 Human Nature: Wise vs. Animalistic, as seen in Othello Tragedies are amongst the oldest and most quintessential of all genres of storytelling. They tend to follow a specific plot-line and many of the protagonists share traits that label them as the “tragic hero”. These traits (jealousy, anger, etc.) act as the incitement of their collapse, either physically or emotionally, throughout the story. Tragedies also almost always share one thing: a tragic end, usually resulting from the death of this hero. Oftentimes people wonder why human beings have always been drawn to this type of literature. The stories are generally not uplifting and characters that audiences grow attached to meet their demise in devastating ways. However, readers throughout time are continuously drawn to tragedies because they relate to the bare-bones of human nature. Tragedies cite the best and worst of human existence; they pay tribute to the fact that all humans are imperfect beings capable of destruction and desperation. For example, William Shakespeare’s Othello is a prime example of a classic tragic storyline. Shakespeare documents Othello’s undoing in a way that does not seem too sudden or unexpected, even relatable. Even though the play often seems too dramatic, with many theatrical deaths and surprising twists, viewers have been so drawn to it for hundreds of years because of its ability to relate to something inside all people: a bestial core that makes humans no different than the other creatures with which they share the earth. Cook 2 At the beginning of Othello, the protagonist is introduced as understanding and levelheaded. Although Othello understands that his position in Venice is important and that he has been crucial to the safety of the city, he also realized that his ethnicity posed problems with others. In Act I, audiences immediately see the prejudice that Othello faces when his wife Desdemona’s father, Brabanzio, finds out about Desdemona and Othello’s elopement. Brabanzio makes racial slurs towards Othello, claiming that the only way he could have gotten Desdemona to agree to marriage is if he had somehow casted spells and used magic to coax her into a relationship. In one of Brabanzio’s first monologues, he explains in despair: O thou soul thief, where hast thou stowed my daughter? Damned as thou art, thou hast enchanted her, For I’ll refer me to all things of sense, If she in chains of magic were not bound, Whether a maid so tender, fair, and happy, So opposite to marriage that she shunned The wealthy curled darlings of our nation, Would ever have, t’incur a general mock, Run from her guardage to the sooty bosom Of such a thing as thou-- to fear, not to delight (1.2. 63-72) Even after audiences are able to ascertain Brabanzio’s feelings toward Othello (and, one could interpret, the similar feelings of many citizens at the time), it is clear that Othello seems to be above the judgement; he is confident in his abilities and in his choices. Othello speaks poetically and slowly, choosing his words carefully. He is also modest but understands his importance to the citizens of Venice. It is obvious that Shakespeare wanted to characterize Othello in a certain way by making him almost inhumanly “put-together”. He seems to be such Cook 3 an upright citizen that his, in a way, seems too good to be true. How can someone such as Othello, who deserves so much respect but receives relatively little from important people in his life such as Brabanzio, be so calm and slow to anger? An example of Othello’s personality at the beginning of the play can be shown in Act 1, Scene 2; after Iago tries to convince Othello that Brabanzio will try to ruin his and Desdemona’s marriage, Othello responds coolly: Let him do his spite. My services which I have done the signory Shall out-tongue his complaints. ‘Tis yet to know -Which, when I know that boasting is an honour, I shall promulgate-- I fetch my life and being From men of royal siege, and my demerits May speak unbonneted to as proud a fortune As this that I have reached. For know, Iago, But that I love the gentle Desdemona I would not my unhoused free condition Put into circumscription and confine For the seas’ worth (1.2. 17-28) At this point in the play, Othello is so sanguine that even though he is threatened with the annulment of his marriage he acts in confidence, proud of the work he has done for his country and unperturbed by the thought of someone ruining that for him. He expresses that his love for Desdemona conquers all things that could potentially cause him distress. This definitive decision to make Othello this “perfect specimen” of human wisdom and attentiveness seems to take up a greater meaning once the play progresses. As the actions of the plot develop and Iago’s plan to basically ruin Othello’s life unfolds, it is clear that Shakespeare wanted viewers to see a palpable Cook 4 change in Othello’s character. Readers are on Othello’s side, but they realize that his demeanor seems too good to be true. This set level of character allows spectators to track his character arc from the very first extreme to the very last. One of the first examples of Othello’s descent from this “perfection” in his character is in Act 3, Scene 3 when Othello first shows signs of a jealousy that is clouding his thoughts and ruining his judgement. While speaking with Iago, Othello is desperate for information regarding Desdemona’s supposed shady actions and he grills Iago for more details. In distress, he begs Iago : I heard thee say even now thou liked’st not that, When Cassio left my wife. What didst not like? And when I told thee he was of my counsel In my whole course of wooing, thou cried’st ‘Indeed?’ And didst contract and purse thy brow together As if thou then hadst shut up in thy brain Some horrible conceit. If thou dost love me, Show me thy thought. (3.3. 113-120) At this point, Othello has not done anything drastic, but the unravelling of his emotions is starting to show. He expresses a jealousy that was not seen in aforementioned passages and his skepticism is unlike the paragon of self-control that he once demonstrated. Audiences are more likely to empathize with this version of Othello because he displays characteristics that everyone is familiar with: the inability to hide his insecurities, the frustration he feels, etc. It feels natural that Shakespeare would use this version of Othello as a kind of bridge between the “perfect” and “imperfect” versions. Towards the end of the play, it is clear that Othello’s distrust and insecurities have reached an all-time low. He acts in brutish ways; Iago’s mind games have gotten to him Cook 5 successfully and are beginning to destroy him. When he confronts Desdemona for supposedly having an affair with Cassio, one can tell the hopelessness and anguish in his voice as he shouts “By heaven, I saw my handkerchief in’s hand. / O perjured woman! Thou dost stone my heart, / And makes me call what I intend to do / A murder, which I thought a sacrifice. / I saw the handkerchief” (5.2. 67-71). Watching this scene, or even just reading it, one is clearly able to hear the agony in Othello’s voice. It almost sounds as if he does not even believe his own words, as if he is trying to convince himself, even in that last moment, that what he is doing is warrented. His newfound monstrous tendencies have taken over; he acts like a primitive human, justifying the killing of his wife as a sacrifice that needs to be made. Right after this, he proceeds to smother Desdemona, truly demonstrating how far he has fallen from human decency throughout the story. Even though Othello’s actions at the end of the play seem melodramatic, Shakespeare is able to convey the change as natural, though indeed extremely jarring. The death of Desdemona, and then Othello himself, represents this natural progression from grace to a certain level of wickedness. It could be said that Othello’s downward fall actually makes him a more believable character. Shakespeare documents this regression as Othello becoming more and more animalistic; reverting almost back to a state of the barbarism of an early human, victim to his own emotions and unable to overcome his instincts. One of the major themes in Othello is this “fall from grace” by the main character who was introduced as this sort of perfect man, i.e. an “Adam”-type character, in the biblical sense. If Shakespeare is the “God” in his own creation story of this fictional literary universe, then in Othello, Iago acts as the “fallen angel” and makes it his mission to deceive and pressure Othello into retreating from the happiness he once knew to a more carnal, bestial creature. Going along with this biblical motif, Desdemona herself would Cook 6 be the Eve character, acting as a sort of catalyst for the downward spiral of events that unfold because of the actions presented by Iago. Shakespeare realized that even though the chain of events in Othello seem extremely dramatized and even unlikely at times, it is actually a simple re-telling of the first tragedy the world has ever known. Human beings are able to connect with this story, or similar tragedies, because everyone has their own “fall from grace”, be it from the beginning of time or through actions in their own lives. Othello’s transition is written in a seemingly organic way, from birth to tragic death, outlining the circle of life that all humans are able to understand.