Leprosy reactions and deformities - PIEL

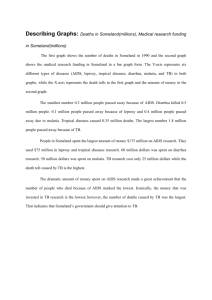

advertisement

Histoid leprosy: a retrospective study of 40 cases from India I. Kaur, S. Dogra, D. De and U.N. Saikia* Departments of Dermatology, Venereology and Leprology *Histopathology, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh 160012, India Correspondence to Inderjeet Kaur. E-mail: sundogra@hotmail.com ABSTRACT Background Rare variants of leprosy pose a diagnostic challenge even to astute clinicians and histoid leprosy is one such form of disease with unique clinical and histopathological features. There are very few large series on this entity, mainly reported from India. Oºbjectives To study the epidemiological and clinical characteristics of patients with histoid leprosy. Methods We undertook this retrospective study including patients registered with the leprosy clinic of our tertiary care referral centre from January 1991 to December 2006. Data regarding demographic details, clinical features, treatment, complications and course following treatment were extracted from the records of the leprosy clinic. Results The incidence of histoid leprosy among the registered patients of our clinic was 1·8% (40 of 2150). There was a significant male preponderance with a male/female ratio of 5·7 : 1. The anatomical areas of involvement were thighs/buttocks (67·5%), arms (62·5%), back (52·5%), face (47·5%), forearms (47·5%) and legs (35%) in descending order of frequency. This variety of leprosy was found most commonly in patients with a primary diagnosis of lepromatous leprosy (40%). De novo histoid lesions, i.e. lesions of histoid leprosy developing without evidence of lesions of other types of leprosy in the Ridley–Jopling classification, appeared in 12·5% of patients only. Only three patients had received antileprosy treatment before presentation. Episodes of erythema nodosum leprosum (ENL) had occurred in 40% of patients, although only one patient manifested ENL after the diagnosis of histoid leprosy. The disease responded satisfactorily to the respective World Health Organization multidrug therapy regimens in all except in one patient who relapsed with borderline lepromatous leprosy. Conclusions As the bacillary load is very high in these patients, they can form a potential reservoir of the infection in the community especially in the postleprosy elimination era. Contrary to the earlier belief in the dapsone era, most of our patients manifested disease without any history of inadequate or incomplete antileprosy therapy. Accepted for publication 25 June 2008 DIGITAL OBJECT IDENTIFIER (DOI) 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08899.x About DOI Article Text The goal of elimination of leprosy was achieved at a global level by the end of 2000. It still remains endemic in four countries of the world.1 In India, despite declaring leprosy elimination at the national level in January 20062 it is still a disease of public health importance in many endemic states of the country, contributing greatly to the total current world caseload. Although millions of patients with classical leprosy have been diagnosed and treated, rare variants of the disease have always eluded and posed a challenge to diagnose, even to trained eyes. Histoid leprosy is one such uncommon form of the disease with unique clinical and histopathological characteristics. The entity initially was recorded in multibacillary patients, on irregular and/or inadequate dapsone (mono) therapy, but later de novo cases were also encountered. Almost 50 years after its description by Wade,3 it remains an interesting enigmatic form of leprosy mostly reported from India. It constitutes 1·2–3·6% of all leprosy cases;4,5 however, studies regarding this form of disease are rare. Ours is a tertiary care centre in Northern India catering to the population of this region in addition to a large migrant population from various states in India where leprosy is still endemic. A systematic retrospective analysis of our leprosy clinic records was carried out to study various epidemiological and clinical characteristics of the patients with histoid leprosy seen over a period of 16 years. Patients and methods This study included patients with biopsy-proven histoid leprosy who attended the leprosy clinic of our centre from January 1991 to December 2006. Clinic records from a predesigned proforma were retrieved and data were collected in respect to demographic details, symptoms, treatment received, reactions, history of contact, and other relevant information. Clinical examination enabled recording of the number and type of lesions, sites involved, nerve involvement and classification of disease based on the established criteria as given in the Ridley–Jopling classification.6 The occurrence of reactions [type 1 (reversal reaction), type 2 (erythema nodosum leprosum, ENL)] independent of histoid status, and neuritis, if present, were noted. Type 1 reaction was defined as increased erythema and oedema in pre-existing lesions with or without the appearance of new lesions or neuritis. Type 2 reaction was defined as the presence of painful evanescent erythematous nodules generally associated with fever with or without neuritis or systemic manifestations. Deformities were graded according to the prevailing World Health Organization (WHO) disability grading.7,8 Slit skin smears (SSS) were taken by standard methods. Leprosy bacilli in SSS of a patient with histoid leprosy are numerous, well preserved and appear long with tapering ends. The bacteriological index (BI) and morphological index (MI) of patients at the beginning of therapy and at regular intervals thereafter, as available, were noted. Histopathological features in haematoxylin and eosin and Ziehl–Neelsen stained skin biopsy specimens were studied to confirm the diagnosis of histoid leprosy, as suggested by Sehgal and Srivastava9 and Wade.10 Several striking features are seen in histoid histopathology, the most prominent being the circumscribed nature of the lesion, the predominance of spindle-shaped and/or polygonal cells, and an unusually large number of acid-fast bacilli better delineated in young active lesions. Patients were treated with multidrug therapy (MDT) according to the recommended WHO guidelines.8,11,12 Between 1982 and 1994, multibacillary patients were treated with 2 years MDT multibacillary regimen (MBR) or until bacillary negativity, whichever was later. Between 1994 and 1998 and subsequently from 1999 onwards, multibacillary patients were treated with 2 years or 1 year fixed duration MDT MBR. After introduction of 12 months MDT MBR in 1998, eight new highly bacillated patients (BI ≥ 4) were also given immunotherapy with Mycobacterium w or bacille Calmette–Guérin vaccines. In addition, patients were given treatment for reactions, deformities or neuritis wherever indicated, according to the established guidelines. Results During the study period, 2150 new patients with leprosy were registered at our clinic. Of these, 40 patients had biopsy-proven histoid leprosy. Thus 1·8% cases of leprosy were of the histoid type. Demographics The age of patients ranged from 13 to 65 years (mean 37). Most (31 of 40, 77·5%) of the patients were between 20 and 60 years of age. Patients comprised 34 men and six women with a male/female ratio of 5·7 : 1. The duration of disease at the time of presentation ranged from 1 month to 12 years (mean 2·86 years). Most (38 of 40, 95%) of the patients were migrants from the neighbouring endemic states. Most of the patients (17 of 27, 63%) were manual laborers from a poor socioeconomic background. Only six (15%) patients had a definite history of contact with another leprosy patient in the family. Clinical findings The number of lesions in the patients varied from one to more than 100, most of them having between 25 and 50 lesions. Nodules/subcutaneous nodules (Figs 1 and 2) were the commonest morphological pattern seen in the majority (33 of 40, 82·5%) of patients, followed by papules (Fig. 3) and infiltrated plaques. Two patients each had atrophic plaques and soft plaques and only one patient had xanthoma-like lesions (Fig. 3). Most of the patients had polymorphic lesions. Ulceration in nodules or plaques was observed only in three (7·5%) patients (Fig. 4). Fig 1. Nodules (a) and plaques (b) over nose, cheeks and ears. Note intervening normal looking skin (c). [Normal View ] Fig 2. Close-up of nodule (a). Small papular lesions (b) at the surrounding area can also be appreciated. [Normal View ] Fig 3. Umbilicated papule (a) resembling molluscum contagiosum with yellowish xanthomalike lesions (b). [Normal View ] Fig 4. Nodular lesions with ulceration and crusting (a). [Normal View ] Development of histoid lesions was most common in patients with the primary diagnosis (Ridley–Jopling classification) of polar lepromatous leprosy (LL) (16 of 40, 40%), followed by subpolar LL (12 of 40, 30%), borderline lepromatous (BL) leprosy (six of 40, 15%) and borderline tuberculoid leprosy (one of 40, 2·5%). De novo development of histoid lesions, i.e. development of histoid lesions in a patient without any evidence of lesions of other manifestations of the disease according to the Ridley– Jopling classification, was found in five (12·5%) patients only. The anatomical areas of involvement were thighs/buttocks (27 of 40, 67·5%), arms (25 of 40, 62·5%), back (21 of 40, 52·5%), face (19 of 40, 47·5%), forearms (19 of 40, 47·5%) and legs (14 of 40, 35%), in descending order of frequency. Most patients (33 of 40, 82·5%) had more than one site of involvement. None of the 40 patients had mucosal involvement. Thirty-nine (97·5%) patients had thickening of two or more peripheral nerve trunks, the ulnar nerve being the most commonly involved followed by the lateral popliteal nerve. Leprosy reactions and deformities Sixteen of forty (40%) patients had experienced ENL during the course of disease, except one who manifested ENL 5 months after starting MDT (Fig. 5). In patients who had ENL, it was present for a mean period of 8·4 months (range 1 month–2 years) prior to the diagnosis. Seven patients had more than one episode of ENL. Deformities were noted in 10 (25%) patients. Five (12·5%) patients each had grade 1 and 2 deformities. Fig 5. Erythematous inflammatory nodular lesions of erythema nodosum leprosum (a) over back. [Normal View ] Slit skin smear and histopathological findings Initial BI and MI from histoid lesions were available for all the patients. SSS from histoid lesions revealed abundant organisms occurring singly, in clusters, or in globi. Most of the organisms were well preserved, appearing long with tapering ends as compared with lepra bacilli in patients with other types of leprosy. The mean baseline BI was 4·6 (range 3–6). The mean MI was 4% (range 0–10%). Histopathological findings in histoid leprosy lesions included well-circumscribed lesions in the dermis or subcutis with a subepidermal Grenz zone of sparing (Fig. 6). Compressed tissue in the surrounding area consisted of collagen, elongated histiocytes, and a few fibrous tissue strands forming a pseudocapsule. The lesions were usually composed of spindle-shaped histiocytes arranged in different patterns, and nerve twigs and appendages were generally not involved. The bacilli observed in a histoid lesion were longer than ordinary leprosy bacilli (Fig. 7). They were arranged in groups or parallel bundles along the long axis of the spindle-shaped histiocytes. Occasionally there were foci of epithelioid cells in the substance of the lesion or the surrounding pseudocapsule, commonly known as 'tuberculoid contamination', which is hypothesized to be due to the tuberculoid component of the earlier borderline phase of the disease.13 Fig 6. Photomicrograph showing thinned out epidermis with Grenz zone and dense histiocytic infiltrate in the dermis with spindling running in short fascicles (haematoxylin and eosin; original magnification × 280). [Normal View ] Fig 7. Lepra stain showing strong positivity for acidfast bacilli with beading (Ziehl–Neelsen stain; original magnification × 1375). [Normal View ] Treatment history Only three patients had received specific antileprosy drugs in the past. One patient had defaulted after three doses of MDT MBR and two were treated with dapsone monotherapy. One of those who were treated with dapsone monotherapy received it for 12 years before reporting to our clinic and the other patient received it for 3 months, 8 years previously. The remaining patients had received only nonspecific medications. The disease responded satisfactorily to the respective MDT regimens in all except in one patient who relapsed with BL leprosy. Discussion Histoid leprosy is considered as a well-recognized expression of multibacillary leprosy characterized by typical clinical, histopathological, immunological and bacteriological findings.9 The term 'histoid leprosy' was first coined by Wade in 1960 as a histological concept of bacillary rich leproma composed of spindle-shaped cells along with an absence of globus formation.3 Since then few case series have been published, mostly from India.4,5,14–16 Histoid leprosy has been reported generally to manifest in patients after long-term dapsone monotherapy,10,17 irregular or inadequate therapy.18 However, there are also reports of disease developing as relapse after successful treatment19 or even appearing de novo without a prior history of any antileprosy treatment.20 The pathogenesis of this rare and unusual variant of leprosy still remains unresolved. The interplay of genetic factors, immune response and treatment received in a given patient seems to influence the manifestations of histoid leprosy. Although histoid leprosy is considered to be a variant of LL, there exists an enhanced immune response against M. leprae in these patients compared with LL with respect to both cell-mediated (CMI) and humoral immunity.21 An indication in favour of an augmented local CMI is the presence of necrosis and ulceration as observed in some histoid lesions, that might be considered as a localized effort to combat M. leprae.22 Immunohistochemical correlations of increased CMI include increased CD36 expression by the keratinocytes, predominance of CD4 lymphocytes over CD8 lymphocytes, and high numbers of activated lymphocytes and macrophages in the lesions.21 Despite the presence of adequate numbers of macrophages, it has been claimed that they lack the functional property to kill bacilli that exist in high numbers in histoid lesions.21 It is possible that under the influence of M. leprae antigens they lose their bacteriolytic property or produce 'suppressor' cytokines, such as interleukin-10,22,23 that adversely inhibit T cellmediated responses to M. leprae. Studies from India4,5,16 have reported the 20–40-year age group to be most commonly affected. In our study, the greatest proportion of patients was in the fifth decade followed closely by the fourth decade. The male preponderance was comparable with that in the study by Sehgal and Srivastava4 (8·2 : 1) and significantly higher than that in the study by Kalla et al.,16 which showed a male/female ratio of around 2 : 1. Clinically the histoid lesions commonly appear as smooth, shiny, hemispherical, dome-shaped, nontender soft to firm nodules which may be superficial, subcutaneous or fixed deeply under the skin and plaques or pads appearing on otherwise normal-looking skin.24 In our series, nodules/subcutaneous nodules were the commonest morphological pattern and a significant proportion of patients had more than one type of lesions. The other rare types of presentations may include scrotal sinuses,25 xanthomatous lesions26 and umbilicated lesions resembling molluscum contagiosum.27 The lesions are usually located on the face, back, buttocks and extremities and over bony prominences, especially around the elbows and knees. Histoid lesions have a preferential centrofacial distribution over the forehead, tip of the nose, chin and cheeks.24 In our patients, arms and buttocks/thighs were the commonest sites of involvement; however, none had mucosal involvement. Most of the patients in our series were previously untreated. Only three patients (7·5%) had received antileprosy treatment for an inadequate period. This figure is significantly less than that reported by previous workers.4,16 Histoid leprosy has generally been considered to occur in patients with LL who relapse after many years of apparently successful monotherapy with dapsone. Hence, the hypothesis that there is a propensity to develop histoid lesions in patients with leprosy who are inadequately treated or have received dapsone monotherapy for a long time seems to be debatable. Sehgal28 has recently reported a patient with histoid leprosy who spontaneously developed histoid lesions without prior clinical evidence of LL and absence of any antileprosy treatment in the past. The author has speculated that histoid leprosy has a distinct position in the leprosy spectrum and that it might not be justified to consider histoid leprosy as a variant of LL. ENL is considered to be extremely uncommon in histoid leprosy. There are only a few published case reports of ENL developing in patients with histoid leprosy.29–31 Forty per cent (16 of 40) of our patients had experienced ENL, of whom 17% (seven of 40) had multiple episodes. This figure is significantly higher than in previous studies.9,16 Of 23 patients studied by Sehgal and Srivastava,9 only one had ENL. Similarly, only two of 25 (8%) patients in the study by Kalla et al.16 had ENL. Thus the assumption that ENL is uncommon in patients with histoid leprosy may not be entirely true. It would be more plausible to hypothesize that ENL reactions are not common in established histoid disease, although they can be a commonly observed phenomenon in a given patient during transition to manifest histoid. There is no clear recommendation regarding the treatment regimens for histoid leprosy. As some workers have considered it to be a variant of LL disease, it has been treated on the lines of multibacillary leprosy. With the advent of the new era of more effective treatment (MDT) modalities available for multibacillary leprosy, the same regimens can be applied to the patients with histoid disease. The addition of the Mycobacterium w vaccine to standard MDT induces a lepromin response of a significantly higher magnitude than that observed with MDT alone in multibacillary leprosy.32 Histoid leprosy being a highly bacillary form of leprosy and concern regarding the efficacy of fixed dose (12 months, after 1998) MDT MBR in highly bacillated patients in some quarters prompted us to add immunotherapy to MDT MBR. Researchers have also used ofloxacin in combination with standard MDT MBR33 or pefloxacin34 alone in treatment. It is the general belief that histoid disease requires longer for bacteriological clearance than does LL; however, no clear trend is emerging from our study because of limited follow up in the majority of the patients. Although the risk of relapse is theoretically possible, there are no data available due to the rarity of this condition and lack of longterm follow up in most of the reports. All except one of our patients, who took adequate MDT, responded well to treatment and there seems no evidence to suggest that M. leprae in this form of disease shows primary or secondary drug resistance. The relapse after successful MDT occurring in the histoid disease could be due either to reinfection or to multiplication of drug-resistant dormant M. leprae.19 Histoid leprosy, including its clinical presentation and pathogenesis, still remains a riddle to the leprosy workers.35 The clinical peculiarities of histoid lepromas are characteristic enough to delineate this entity with certainty in most patients. SSS and histopathological examination of histoid leprosy are mandatory for final confirmation of diagnosis. Although much has been achieved towards elimination of leprosy and leprosy care is being amalgamated into general health services, it should be ensured that this multibacillary form of the disease be identified and treated promptly to decrease the chances of transmission to the general population, as such cases will, in all likelihood, probably continue to occur in the 'postelimination era'. References 1 World Health Organization. Global leprosy situation, 2007. Weekly Epidemiological Records 2007; 82: 225–32. Available at: http://www.who.int/wer/2007/wer8225.pdf (last accessed 22 July 2007). Links 2 Announcement: India achieves national elimination of leprosy. Indian J Lepr 2006; 78:101. Links 3 Wade HW. The histoid leproma. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis 1960; 28:469. (Abstract). Links 4 Sehgal VN, Srivastava G. Histoid leprosy: a prospective diagnostic study in 38 patients. Dermatologica 1988; 177:212–17. Links 5 Singh VV, Singh G, Kaur P, Pandey SS. Histoid leprosy in Varanasi. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 1983; 49:160–1. Links 6 Ridley DS, Jopling WH. Classification of leprosy according to immunity. A five-group system. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis 1966; 34:255–73. Links 7 WHO Expert Committee on Leprosy. Sixth Report. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser 1988; 768:1–51. Links 8 WHO Expert Committee on Leprosy. Seventh report. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser 1998; 874:1–43. Links 9 Sehgal VN, Srivastava G. Status of histoid leprosy – a clinical, bacteriological, histopathological and immunological appraisal. J Dermatol 1987; 14:38–42. Links 10 Wade HW. The histoid variety of lepromatous leprosy. Int J Lepr 1963; 31:129–42. Links 11 WHO Study Group. Chemotherapy of leprosy for control programmes. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser 1982; 675:1–33. Links 12 WHO Study Group. Chemotherapy of leprosy. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser 1994; 847:1–24. Links 13 Crocos MG, Crocos CD. 'Tuberculoid contamination' in histoid hanseniasis. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis 1994; 62:301–5. Links 14 Malik R, Khandpur R, Chandra K, Singh R. A clinico-pathological study of 244 cases of leprosy with special reference to histoid variety. Lepr India 1977; 43:400–5. Links 15 Salodkar AD, Kalla G. A clinico-epidemiological study of leprosy in arid northwest Rajasthan, Jodhpur. Indian J Lepr 1995; 67:161–6. Links 16 Kalla G, Purohit S, Vyas MC. Histoid, a clinical variant of multibacillary leprosy: report from so-called nonendemic areas. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis 2000; 68:267–71. Links 17 Price EW, Fitzherbert M. Histoid (high-resistance) lepromatous leprosy. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis 1966; 34:367–74. Links 18 Ramos-Caro FA. Histoid lepromas. Cutis 1982; 30:108–9. Links 19 Shaw IN, Ebenezer G, Rao GS et al. Relapse as histoid leprosy after receiving multidrug therapy (MDT); a report of three cases. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis 2000; 68:272–6. Links 20 Kamath HD, Sukumar D, Shetty NJ, Nanda KB. Giant lesions in histoid leprosy – an unusual presentation. Indian J Lepr 2004; 76:355–8. Links 21 Kontochristopoulos GJ, Aroni K, Panteleos DN, Tosca AD. Immunohistochemistry in histoid leprosy. Int J Dermatol 1995; 34:777–81. Links 22 de Waal Malefyt R, Haanen J, Spits H et al. Interleukin-10 (IL-10) and viral IL10 strongly reduce antigen specific human T-cell proliferation by diminishing the antigen-presenting capacity of monocytes via downregulation of class II major histocompatibility complex expression. J Exp Med 1991; 174:915–24. Links 23 Sieling PA, Abrams JS, Yamamura M et al. Immunosuppressive roles for IL-10 and IL-4 in human infection. In vitro modulation of T cell responses in leprosy. J Immunol 1993; 150:5501–10. Links 24 Sehgal VN, Srivastava G. Histoid leprosy. Int J Dermatol 1985; 24:286–92. Links 25 Shivaswamy KN, Thappa DM, Laxmisha C. Scrotal sinuses in histoid leprosy. Indian J Lepr 2004; 76:231–2. Links 26 Thappa DM, Karthikeyan K, Vijaikumar M, Laxmisha C. Histoid leprosy masquerading as tuberous xanthomas. Indian J Lepr 2001; 73:353–8. Links 27 Mohan L, Bhatia PS, Nigam P et al. Molluscum contagiosum type lesions in histoid leprosy. J Indian Med Assoc 1992; 90:106. Links 28 Sehgal VN. Spontaneous appearances of papules, nodules, and/or plaques: a prelude to abacillary, paucibacillary, or multibacillary histoid leprosy. Skinmed 2006; 5:139–41. Links 29 Kumar V, Mendiratta V, Sharma RC et al. Erythema nodosum leprosum in histoid leprosy: a case report. J Dermatol 1997; 24:611–14. Links 30 Kaur S, Dhar S, Sharma VK, Ray R. Erythema nodosum leprosum in case of histoid leprosy. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis 1993; 61:292–3. Links 31 Sehgal VN, Gautam RK, Srivastava G et al. Erythema nodosum leprosum (ENL) in histoid leprosy. Indian J Lepr 1985; 57:346–9. Links 32 Sharma P, Kar HK, Misra RS et al. Induction of lepromin positivity following immuno-chemotherapy with Mycobacterium w vaccine and multidrug therapy and its impact on bacteriological clearance in multibacillary leprosy: report on a hospital-based clinical trial with the candidate antileprosy vaccine. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis 1999; 67:259–69. Links 33 Vora NS, Vora VN, Mukhopadhyay AK et al. A case of histoid leprosy responding to ofloxacin along with standard MDT. Indian J Lepr 1995; 67:183– 6. Links 34 Mahajan PM, Jadhav VH, Mehta JM. Pefloxacin in histoid leprosy. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis 1994; 62:297–8. Links 35 Palit A, Inamadar AC. Histoid leprosy as reservoir of the disease; a challenge to leprosy elimination. Lepr Rev 2007; 78:47–9. Links