SARBANES-OXLEY ACT OF 2002 a

advertisement

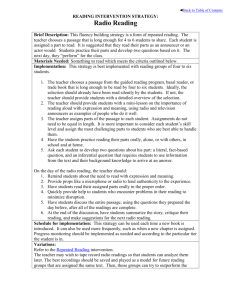

CAPITAL MARKET REACTIONS TO THE SARBANES-OXLEY ACT OF 2002 Zabihollah Rezaee* Thompson-Hill Chair of Excellence & Professor of Accountancy Fogelman College of Business and Economics 300 Fogelman College Admin. Building The University of Memphis Memphis, TN 38152-3120 Phone: (901) 678-4652 Fax: (901) 678-0717 E-Mail: zrezaee@memphis.edu Pankaj K. Jain Assistant Professor of Finance Fogelman College of Business and Economics 300 Fogelman College Admin. Building The University of Memphis Memphis, TN 38152-3120 Phone: (901) 678-3810 Fax: (901) 678-2685 E-Mail: pjain@memphis.edu Submitted for presentation at the Spring 2003 Accounting Research Consortium Comments welcome. Please do not quote or circulate without permission. Current version: March 2003 * Corresponding Author. CAPITAL MARKET REACTIONS TO THE SARBANES-OXLEY ACT OF 2002 ABSTRACT The Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 (the Act) was enacted in response to numerous corporate and accounting scandals and aimed at reforming business practices of the financial community and the accounting profession. This study examines the market reaction to the Act and finds a positive abnormal return at the time of several events leading to the passage of the Act. Furthermore, firms with higher market capitalization, earnings to price ratio, and stock price volatility are affected more by the Act compared to other firms. Results suggest that the Act created news which was viewed as good news by investors in increasing the market’s confidence in firms’ corporate governance and accounting systems. Keywords: Financial scandals; the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002; market reactions; corporate governance Data Availability: Data are commercially available from the sources identified in the study. JEL Classification: G14; G28; M41 CAPITAL MARKET REACTIONS TO THE SARBANES-OXLEY ACT OF 2002 I - INTRODUCTION Two thousand two was a challenging and rather difficult year for corporate America as evidenced by the stock market’s swift decline, a significant number of earnings restatements, substantial corporate and accounting scandals and resulting loss of confidence in corporate governance, financial reports, and related audit functions. To restore public confidence, lawmakers enacted bipartisan legislation by passing the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 (hereafter the Act) in July 2002. A major reason for enactment of the Act and establishment of the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) related implementation rules was the belief that new regulations were necessary to make corporations more accountable to shareholders and to restore the confidence of investors in the capital market. However, the Act has received a mixed response from the financial community and the accounting profession. The Act was viewed by many as the most sweeping measures taken by legislators addressing corporate governance, financial reports, and audit functions.1 Results of a real-time poll of 450 CFOs and senior financial executives during a live webcast with former SEC chairman Arthur Levitt revealed that 90 percent of participants believe new regulations intended to make corporations more accountable to shareholders are necessary (Levitt 2002). Others consider the Act as patchworks and codification responses by Congress to widely publicized business and accounting scandals, with no direct impacts on improving corporate governance and financial disclosures, at least beyond those of market-based mechanisms.2 Sorin, et al. (2002) argue that although the Act may In signing the Act, President George W. Bush described it as “the most far-reaching reforms of American business practice since the time of Franklin Delano Roosevelt” (Bumiller 2002). The SEC Commissioner, Harvey Goldschmid, called the Act the “most sweeping reform since the Depression-era Securities Laws” (Murray 2002a). 2 See Cunningham (2003) and Ribstein (2002) for the indepth critique of the Act and the discussion of market versus regulatory responses to financial scandals. 1 1 improve future investor confidence, it does not provide restitution to investors who lost their investments because of financial scandals, and to securities professionals the Act gives the illusion of increased accountability. There exists an extensive literature, propagated mostly by economists, accountants and lawyers, on the Act and its possible impacts on public companies’ corporate governance, financial reporting process, and audit functions. These writings (Rezaee 2002; Osterland 2002; IIA 2002; Ribstein 2002; Sorin et al. 2002; Cunningham 2003) concentrate on analyzing specific provisions of the Act and their impacts on financial, business, and accounting communities. The conclusions reached on the various effects of the Act, therefore, are based generally on this descriptive evidence which range from “sweeping measures” that will eventually reform corporate governance and the financial reporting of public companies to “patchworks, codifications and further studies” of the existing corporate governance and financial disclosures regulations and requirements. The major theme of these studies is that despite characterization of the Act as either “sweeping reform” or “patchworks and codifications,” it is intended to and will restore investor confidence in the capital markets. The purpose of this study is to empirically test capital market reactions to several events (Congressional bills) leading to the passage of the Act. Empirical market-based accounting research3 typically examines the market reactions to the announcement of particular events (e.g., accounting standards, regulations) via analysis of the relation between these events and various market variables. Consistent with empirical marketbased accounting research, this study examines whether the announcement of nine events (see Table 1) leading to the passage of the Act provided any new information to investors that may have affected their perceptions of the likelihood of the passage of the Act and its impacts on 3 See Easton (1999) for implications of this type of research in market event studies. 2 public companies’ corporate governance, financial reports, and audit functions. Specifically, we (1) examine capital market reactions to nine events leading to the passage of the Act to determine whether the Act conveys value-relevant information to investors in restoring the market’s confidence in corporate America, and (2) investigate whether the detected market reactions are associated with company characteristics and attributes (e.g., corporate governance, financial reports, and audit functions). We detected positive abnormal returns around dates corresponding to the passage of the Act suggesting the capital market reacted positively to the Act. We also investigated the determinants of the detected price reaction by using firm specific variables. We found that firms with higher market capitalization, earnings to price ratio, and stock price volatility were affected more by the Act compared to other firms. Results also indicate that financial scandals were not limited to a handful of companies because investors perceived them to be an industry-wide problem. The results of this study have implications for public companies and their executives, investors, and policy makers. The results suggest that investors value regulations such as the Act that create positive changes in corporate governance, the financial reporting process, and audit functions. Public companies and their senior executives should realize that they will be under scrutiny to conduct their business ethically and thus should have a long-term focus on improving corporate governance and financial reports, as the capital markets and rating agencies will likely factor these improvements and firm characteristics, including corporate governance, more explicitly into their valuation and rating processes. Policy makers (Congress) and regulators (SEC) should be encouraged regarding the important oversight role of restoring public confidence in corporate America. Our results suggest that the Act has created a climate of confidence in financial information and therefore more investors’ confidence in the capital 3 markets and the economy. This study contributes to the extant literature on law and finance, examining the relationship between the legal protection of investors and the development of financial markets. Results support the findings of Laporta et al. (1998), documenting that legal systems including legislations and regulations are important integral components of corporate governance and corporate finance. The remainder of the paper proceeds as follows: The next section discusses the effects of major provisions of the Act. Section III briefly reviews the related literature. Theoretical framework, events leading to the passage of the Act, and testable hypotheses are presented in Section IV. Section V discusses data and methodology. Results are presented in Section VI and a final section concludes the paper. II – PROVISIONS OF THE ACT President Bush signed into law, on July 30, 2002, the Public Company Accounting Reform and Investor Protection Act of 2002, better known as the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 (the Act). This Act addresses the conduct and role of corporate boards, executives, accountants, auditors, lawyers, investment banks, financial analysts, regulators, and standard-setting bodies in the financial reporting process. The Act’s main purpose is to restore integrity to financial markets and confidence in corporate conducts, financial reports, and related audit functions. The Act establishes an independent regulatory structure for accountants who audit public companies, creates increased disclosure and reporting requirements to improve transparency of financial reports, changes accountants’ relationships with their clients and audit committees, increases criminal penalties for violations of securities and related laws, requires senior executives to certify reports filed with the SEC, and imposes substantial and unprecedented requirements on public companies, their directors, officers, and accountants to improve corporate governance. 4 The Act was enacted to respond to an increasing number of financial restatements by prominent companies, a series of high profile alleged financial statement fraud, an erosion in market confidence, and extreme market volatility. The Act requires corporate executives to certify the accuracy of company financial reports with the threat of civil and criminal penalties. There are primarily two types of certification requirements. The first type, certifications of periodic financial reports filed with the SEC after August 29, 2002, requires each officer (chief executive officer, CEO and chief financial officer, CFO) to affirm that the filed report is accurate and complete and accordingly, the financial statements and other financial information are in all material respects fairly presented.4 The second certification pertains to the company’s “disclosure controls and procedures” which goes beyond the existing requirements of internal control. In every periodic report filed with the SEC for periods ending after August 29, 2002, CEOs, CFOs and/or other certifying officers affirm, among other things, that they are responsible for establishing and maintaining disclosure controls and procedures, and they have evaluated the effectiveness of the disclosure controls and procedures. Many provisions of the Act require the SEC and other regulators to establish additional regulations and rules (certification, disclosure controls and procedures, codes of ethics) or perform further studies (audit firm rotation, investment banks). Although the implications of some provisions of the Act are not immediately obvious (establishment a of public company accounting oversight board, attorney reporting, audit committee requirements), many of the Act’s provisions take effect currently (reporting requirements, senior executives’ certifications, 4 Prior to the passage of the Act, the SEC, on June 27, 2002, ordered the principal executing and financial officers (CEOs, CFOs) of each registrant with revenue over $1.2 billion during its last fiscal year to file statements under oath on the registrant’s cover reports. The sworn statements were required to be filed on or after August 14, 2002 on the first date that a Form 10-K or 10-Q must be filed (SEC 2002). 5 actions prohibiting fraudulently influencing an audit, loans to directors and officers). Survey studies (IIA 2002) and anecdotal evidence (Makinson-Cowell 2002; Osterland 2002) document that the passage of the Act has had considerable effects on corporate governance structure (composition and functions of boards of directors and audit committees), the financial reporting process (off balance sheet financing, executive compensation, more conservatism, certification of financial statements), and audit functions (auditors’ objectivity, effectiveness, and credibility). These effects are expected to improve investors’ confidence in capital markets, which has significantly eroded in recent years, and therefore investors will benefit from provisions of the Act and related SEC implementation rules. Critics of the Act (e.g., Sorin et al. 2002; Cunningham 2003) argue that all the changes made by the Act had either already been in effect as a matter of custom, practice, and/or regulatory requirements or been discussed and/or proposed by corporate governance advocates or organized stock exchanges. Proponents of the Act (e.g., Congress, SEC) believe that the Act contains many sweeping measures that will eventually reform corporate governance, financial reports, and audit functions. III - REVIEW OF LITERATURE In this section, the relationship between regulations and stock prices is reviewed in providing a framework for our study. Several related studies examine securities price reactions to the Securities Act of 1933, the Securities Act of 1934, and the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995. These Acts (1933, 1934) were intended to protect investors from fraudulent or misleading information by increasing the general extent of accounting disclosures and restricting accounting alternatives. Ingram and Chewning (1983) examine the percentages of annual cumulative abnormal returns for years before and after the Securities Acts and find aggregate market responses during fiscal years of the pre-Act periods (1926-1933) than during 6 the fiscal years post-Act periods (1935-1940). Chow (1983, 1984) examines the impacts of the Acts (1933 and 1934) on bondholder and shareholder wealth and concludes that the Securities Act of 1933 reduced shareholder wealth through inter-firm wealth transfers, out-of-pocket compliance costs, and reduced opportunity sets. Benston (1973) investigates the impact of the Securities Act of 1934 on the behavior of securities and finds no significant and measurable effect of the Act, suggesting that there was no benefit of the legislation for investors. These studies document that although both the 1933 and 1934 Securities Acts considerably increased public companies’ financial disclosures, they did not have significant impacts on security market behavior. The Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995 (PSLRA) had increased restrictions on private litigants’ ability to sue for investment losses from securities fraud. Several studies examine the capital market reactions to the PSLRA for firms in high-litigation-risk industries (e.g., computers, electronics, pharmaceuticals/ biotechnology, and retailing). Spiess and Tkac (1997) and Johnson et al. (2000) investigate stock price reaction to several events leading to the enactment of the PSLRA including the presidential veto on 12/19/95 and the congressional votes to override the veto on 12/20/95 (House) and 12/22/95 (Senate). These studies conclude that investors considered the PSLRA beneficial by documenting significantly negative abnormal returns for firms in high-litigation-risk industries on 12/18/95 (veto rumors) and significantly positive abnormal returns on 12/20/95 (the House override of veto). Ali and Kallapur (2001) find evidence that is inconsistent with results of Spiess and Tkac (1997) and Johnson, et al. (2000). Ali and Kallapur (2001) document that: (1) conventional statistical procedures overstate the negative abnormal returns on 12/18/95 detected by previous studies; (2) the positive excess returns observed on 12/20/95 are more likely in response to the presidential veto than the House 7 override; and (3) the detected significant abnormal returns for events other than the presidential veto suggest that investors consider the PSLRA harmful. Thus, empirical results pertaining to the important PSLRA are inconsistent and controversial. Like the Securities Acts of 1933 and 1934 as well as the PSLRA of 1995, the SarbanesOxley Act of 2002 was enacted to address corporate misconducts and the related business and accounting scandals that eroded investors’ confidence in the capital markets. Unlike the previous Acts, the Sarbanes-Oxley Act contains sweeping measures dealing with corporate governance, financial reporting, conflicts of interest, corporate ethics, disclosure controls and procedures, new civil and criminal penalties, and the new regulatory structure for the oversight of the accounting profession. In addition, unlike other related regulations, certain provisions of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act are effective immediately, whereas other provisions require the SEC to issue implementation rules to carry out the purposes of the Act. Thus, the potential impacts of provisions of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act on investors confidence are worthy of investigation. Laporta et al. (1988) document that the extent to which a country’s laws and regulations protect investor rights and the extent to which those laws and regulations are enforced determine the ways in which corporate governance and corporate finance evolve in the country. Laporta et al. (1997) find that better legal protection improves investor confidence and leads investors to accept a lower rate of returns which in turn encourages companies to use external finance when rates are lower. Marketplace mechanisms often, as evidenced by recent business and accounting scandals (e.g., Enron, WorldCom, Global Crossing, Xerox, Tyco, Qwest, among others), do not provide timely and effective self-corrections. Therefore, laws (the Act) are expected to create an environment which promotes strong marketplace integrity and investor trust in the reliability, quality, and transparency of financial disclosures. 8 IV - THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK, EVENTS, AND HYPOTHESIS 1. The Possible Impacts of the Act A survey of institutional investors shows that investors are unimpressed with Section 302 of the Act requiring certification of financial statements by corporate executives, and they believe that the implementation of other provisions (e.g., audit committee composition and functions, disclosure controls, new public oversight board, severe penalties for violations of Securities laws) of the Act will be more effective in restoring public confidence in financial reports (Makinson-Cowell 2002). Despite all attention by media and financial press, certification of financial reports, initially required by the SEC for large companies and subsequently extended by the Act to all publicly traded companies, has always been a requirement of the federal securities laws (Langevoort 2002). Bhattacharya et al. (2002) document that the capital market was not surprised by the SEC certification requirements. Certification requirement events provide no new value-relevant information to the capital market because they neither established any credibility of management financial disclosures nor did they create an environment which can be used to evaluate the truthfulness of management’s representation. Thus, any possible information content of certification events has been impounded into the market price long before the requirement becomes available. Although, the Bhattacharya et al. study focuses on the SEC initial certification requirements for large companies, it incidentally finds an increase in market volume on July 25, 2002 (congressional legislation), and positive abnormal market return on August 14, 2002. The Act is intended to restore the investing public’s confidence in corporate America, financial reports, and audit functions. The Act could also have psychological rather than substantive effects (Cunningham 2003). Despite the significance of the substantial effects of the 9 Act, it created news that investors could consider as “good news” in revitalizing the capital markets. Anecdotal evidence and results of surveys (IIA 2002) indicate that affected public companies are changing their corporate governance structure (composition and functions of the board of directors and audit committee), relationship with their independent auditors (restricting the scope of non-audit services), and design and structure of their disclosure controls and procedures to comply with provisions of the Act. It is expected that these required changes will improve public companies’ corporate governance, the quality, reliability, and transparency of financial reports, and the effectiveness of audit functions. Market participants should view these improvements as a major step toward restoring confidence in financial reports and capital markets. 2. Events Leading to the Passage of the Act The final passage of the Act, on July 30, 2002, was affected by many congressional proposals and bills that anticipated the eventual enactment of the Act, starting with the introduction of H.R. 3763 on February 14, 2002 in the House of Representatives. During this deliberation process, several congressional legislations were introduced and debated (See Table 1). When the Act was finally enacted, the capital market was saturated entirely with bad news of corporate and accounting scandals as well as the lengthy economic depression. Therefore, it is difficult to separate the effect of the Act on the stock market from other business and economic events. Furthermore, it is necessary to determine when and how the legislation might have affected the capital market because of possible anticipation by the market during the deliberation process in a manner that when passed, its effects had already been discounted. The main difficulty in determining stock price reactions to a set of related legislative events is identifying when the market first anticipates the possible effects of such events (Binder 1985; Ali and 10 Kallapur 2001). It is expected that the capital market, during almost one year of legislative debate after the collapse of Enron and the introduction of several bills in both the House and the Senate, would have anticipated the likelihood of the passage of the Act and its possible effects. Consistent with prior research (Espahbodi et al. 2002; Cornett et al. 1996), we used multiple information sources in identifying the events. The initial step taken to identify key events was to search the SEC and congressional websites looking for press releases for the events pertaining to the Act as listed in Table 1. We next searched the Wall Street Journal index (WSJI), the Wall Street Journal (WSJ), and the New York Times (NYT) to confirm and/or identify the event dates.5 Each of the nine events are potentially significant to investors as they inform investors of the likelihood of the Act being passed and its possible impact on corporate governance, the financial reporting process, and audit functions. Two major reform bills were initially introduced. The weaker bill was proposed in the House by Financial Services Committee Chairman Michael Oxley (R-Ohio), and the tougher one was introduced in the Senate by the Senate Banking Committee Chairman Paul Sarbanes (D-Maryland) (see Table 1).6 As of June 2002, the likelihood of the passage of either bill or combination of both was uncertain. The WorldCom debacle in June 2002, which resulted in the largest corporate bankruptcy in the United States history, necessitates Congressional action. Cotton (2002) reports that shareholders lost $460 billion in the Enron, WorldCom, Qwest, Global Crossing, and Tyco debacles. The substantial investment loss by shareholders, employees, and pensioners, widelypublicized earnings restatements, and alleged financial statement fraud by high profile companies along with the perceived inability of market self-corrections created political capacity 5 The WSJI, WSJ, and NYT typically report the press release announcements of these events one day after the event date. The announcement dates listed in Table 1 are from the SEC and congressional websites. To capture the full impacts of these events we use a three-day event window around event dates. 6 There were other versions of the reform bills introduced in both the House (H.R 3818, LaFalco, the Committee on Financial Services) and in the Senate (S.2004, Dodd, the Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs). 11 in Congress for reform-minded legislators to regulate corporate and accounting reforms. The result was the compromised bipartisan Sarbanes-Oxley Act which gained momentum rapidly in the weeks before its enactment on July 30, 2002. However, there were some uncertainties regarding the form, content, and the possibility of the passage of the Act in the weeks prior to its enactment. During these six months of intensive legislative debate, the capital market received controversial signals from both the House and the Senate regarding the content, substance, and likelihood of the passage of the Act. Langevoort (2002, 5), in discussing post-Enron reform agenda and referring to the initial bills introduced in the House and the Senate, argues that “the Republican agenda was hardly real institutional reform at all, except timidly in the accounting area… The Democratic agenda more willingly tapped into that discontent, but still faced a difficult implementation problem.” Although the intent of both Congressional bills (S. 2673 and H.R. 3763) was to restore investors’ confidence in corporate governance and financial reports, there were significant differences between the House bill and the Senate amendment. The capital market perceived these differences as a signal of the decreasing likelihood of the passage of the Act (events of July 15, 16, and 19, 2002). Events pertaining to the conference report indicating the congressional conference committee reached an agreement to comprehensive reform legislation (the Act) on July 24, 2002, the congressional legislation on July 25, 2002, sending the compromised bill to the president on July 26, 2002, and all rumors about the president signing the compromised bill sent signals to the market which indicated the increasing likelihood of the passage of the Act. Thus, the focus of this study is on the events that changed the likelihood of the passage of the Act. The occurrence of several legislative events prior to the enactment of the Act (from February 2002 through July 2002) and the availability of data provide an opportunity to test the 12 capital market reactions to these congressional events. Thus, it is possible to measure the stock market effect of the legislation during this relatively short and distinct period. 3. Hypothesis Many provisions of the Act might have symbolic value and through signaling effects, influence market participants’ confidence in the securities market. Examples of these provisions are: (1) senior executive certification requirements disclosing the already mandated certifications under Securities Laws; (2) real-time disclosure of key information concerning material changes in financial condition or operations signaling the potential business and financial risks and a discussion of their probability and magnitude from management’s perspective; (3) separation of audit and non-audit services which can signal the markets about the objectivity and effectiveness of audit functions and resulting impacts on credibility of published audited financial statements; (4) improved corporate governance by signaling a more vigilant board of directors and audit committees (e.g., approval of audit and non-audit services, code of ethics, financial expertise, loans to directors); (5) disclosure controls and procedures requiring public report on management’s assessment of controls effectiveness and auditors’ attestation and report on management’s control assertions; (6) whistle-blowing protections for employees who lawfully provide information which they reasonably believe constitute violations of Securities Laws; (7) increased criminal penalties for violations of securities and other applicable laws and regulations; and (8) creation of the public company accounting oversight board (PCAOB) signaling the improved changes needed in the self-regulatory structure of the auditing profession. Proponents and opponents of the Act have presented several descriptive theoretical arguments to support their views of the Act as either “sweeping reforms of corporate America” or “patchwork responses to recent financial scandals” respectively. Our study contributes to this 13 ongoing debate by empirically examining capital market reactions to the Act. The main issues addressed in this study are (1) whether the capital market reacted positively to the events leading to the passage of the Act, and (2) whether the implementation of provisions of the Act affects companies differently. Thus, we propose the following (alternative) hypotheses against the null hypothesis of no reaction: H1: Ceteris paribus, stock prices reacted positively to events leading to the passage of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002. H2: The detected market reactions were associated with the firm’s attributes (corporate governance characteristics). The firm-specific characteristics that we examine include market capitalization as a proxy for firm size, market to book ratio, earnings to price ratio, earnings retention rate, debt to capital ratio, firm’s auditor, auditor’s opinion of the financial statements, earnings restatements, and firm’s idiosyncratic risk. These variables can directly or indirectly influence the quality, reliability, and transparency of financial reports. Bigger firms with diverse operations are perhaps more susceptible to accounting irregularities. Higher market to book ratio and lower earning to price ratio also indicate that a larger proportion of firm assets are intangibles that are difficult to measure accurately. Thus, these firms are under closer scrutiny for accounting irregularities. Higher earnings retention ratios also empower the management’s capability to create fictitious earnings and assets. In contrast, lower retention and higher payout make it more costly to engage in such activities because then the earnings increases have to be supported by hard cash. Auditor brand name can have an important effect on investor’s confidence especially in light of the high profile scandals that have emerged recently. Auditor’s opinion on a firm’s financial statements can also reflect their reliability and credibility. We include a firm’s overall variance of stock prices as an additional measure of the accuracy with which a firm’s potential 14 can be forecasted. Although most financial models suggest that only systematic risk is priced and idiosyncratic risk can be diversified away, some recent papers suggest that idiosyncratic risk matters to investors (Goyal and Santa-Clara 2002). Accounting manipulation and resulted earnings restatements have received considerable attention from regulators. For example, former SEC chairman Levitt (1998) expressed concern about erosion of the quality of accounting earnings and its impact on investor confidence and market volatility. Earnings restatements during 1995-2002 are used as proxies for earnings management and manipulation. V. DATA AND METHODOLOGY The Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 is applicable to all publicly traded companies. Therefore, we expect the stock market as a whole to react positively to the events around the passage of the Act. Our first test focuses on two broad based market indices, namely, the S&P 500 index and the Value-line index. 7 The sample period for our events is from February to August 2002. For each index, abnormal returns around the relevant events are calculated using the constant-mean return model.8 The estimation period for the normal (benchmark) return starts from 142 trading days before February 2, 2002 and ends at 21 trading days before that date. The event-day abnormal returns (AR) are then calculated as the day’s gross return minus the normal 7 S&P 500 is a value-weighted index and is widely regarded as the standard for measuring large-cap U.S. stock market performance. In contrast, the Value-line index is an equally-weighted index, which averages the returns on 1700 stocks. The historical values for the indices we use are readily available on their respective websites http://www.spglobal.com and http://www.valueline.com. 8 Procedures for estimating abnormal returns (AR) are standard in the literature (see Brown and Warner 1985; Campbell et al. 1997). Two distinct models are typically used in calculating ARs – the constant-mean return and the market model. We could not use the more popular market model for our first test primarily because the Act affects all publicly traded companies and thus the portfolio under investigation is the market portfolio itself. Prior studies (e.g., Rezaee 1990; Stice 1991; Bhattacharya et al. 2002) use the constant-mean return model for investigating the capital market reactions around accounting standards and legislative events. The market reaction in Table 4 is tested using the constant-mean return model based on the following equation: ARMt RMt R Mt , 142,21 where ARMt = abnormal market return on the event date, RMt = actual market return on the event date, and R Mt , 142, 21 = the mean market return (benchmark) during the 121 trading days during the estimation period. The conventional t-test was used to determine the statistical significance level of observed abnormal returns. 15 return. The 3-day cumulative abnormal returns (3-day CARs) are obtained by adding the abnormal returns on the event day, one day before the event, and one day after the event. These time-series tests help us investigate the market reaction around each event leading to the passage of the Act, as set out in Table 1. We investigate the time series capital market reactions to the Act as reflected in the price relatives derived from the Standard and Poors 500 Series. After identifying the events with significant overall market reaction, we conduct a crosssectional analysis of the constituent firms in the S&P 500 index. The purpose of these tests is to identify the firm-specific characteristics that influence the magnitude of stock price reactions to the passage of the Act. Firm-specific variables are obtained from various sources. Definitions of these variables used in the cross-sectional analysis and their data sources are presented in Table 2. The cross sectional analysis simultaneously analyzes the impact of these variables on abnormal returns and cumulative abnormal returns in a regression framework. We use the standard event study methodology for the cross sectional analysis as outlined in Campbell, et al. (1997). The dependent variable for the first regression is abnormal returns (ARit) defined as follows under the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM): ^ ARit Rit R f ( RMt Rf ) (1) where Rit is the return on stock i on event date t; -hat is the stock’s beta which measures the sensitivity of a company's stock price to the fluctuation in the Standard & Poor's 500 (S&P 500) Index, calculated for a 5-year period ending on June 2002 using month-end closing prices including dividends; Rf is the risk-free rate of return from treasury bill (t-bill); and RMt is the return on S&P 500 Index on the event date. 16 The dependent variable for our second regression is cumulative abnormal returns (CARit) which is obtained by adding the abnormal returns on the event date, one day before the event and one day after the event as follows: CARit ARit 1 ARit ARit 1 (2) We developed two regression models based on cross-sectional variables as follows: ARit 1 MCapi 2 MBi 3 EPi 4Qi 5 DTC 6 AuditAA 7 Opn 8 9 Res tate (3) CARit 1 MCapi 2 MBi 3 EPi 4Qi 5 DTC 6 AuditAA 7 Opn 8 9 Res tate (4) Table 2 presents definitions of variables used in equations 3 and 4 along with related data sources. Panel A of Table 3 lists descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation minimum, maximum) for all variables and Panel B reports correlations between variables. The first row of Panel B shows the Pearson’s correlation coefficients, the second row presents the p-value, and the third row provides the number of pair-wise observations from which the first two rows are calculated. Sensitivity Analyses The possible impacts of the Act may differ from industry to industry depending on the industry business and accounting practices as well as the corporate governance structure and the quality of financial reports. Although the implementation of provisions of the Act is expected to affect publicly traded companies in all industries, it was originally aimed at addressing financial scandals of high profile public companies. The Enron, WorldCom, Global Crossing, and Qwest scandals have reinvigorated the debate over corporate regulation to restore confidence in the capital markets. Marketplace and corporate governance mechanisms were unable to detect and 17 prevent these scandals, investors suffered substantial losses and Congress responded with the Act. Cunningham (2003) refers to these four financial scandals as the “Big-Four” accounting frauds, which set the stage for which the Act was established. Indeed two of the Big-Four companies, Enron and Global Crossing, are mentioned by name in the Act. Cunningham (2003) argues that these Big-Four companies share several common characteristics: (1) they used various accounting shenanigans to cook the books; (2) they employed Andersen as their independent auditor; and (3) three of the Big-Four are in the telecommunications industry with Enron being in the petroleum products industry.9 The pervasiveness of business and accounting scandals in 2002 encouraged Forbes to create “The Corporate Scandal Sheet” online to keep track of these scandals. Starting with the Enron debacle in October 2001, Forbes identifies 21 financial scandals through July 2002 (Forbes 2002).10 We classify these scandals into 11 industries according to their SIC Code and then we reduce the number of industries to five industries with two or more alleged financial statement fraud firms therein. These selected five industries are electric power generation, natural gas distribution, pharmaceutical, petroleum, and telecommunications. To examine shareholders’ response to the Act in these industries, we calculate for event 7 (when the Act was passed by Congress because this event shows higher CAR (See Table 4) and it was assumed that the President would sign it into law) abnormal returns for a portfolio of firms in these five industries. Consistent with Karpoff and Malatesta (1989) and Ali and Kallapur 9 Two of these three common characteristics (financial restatements proxies for the use of accounting schemes and audited by Andersen) were incorporated into our cross-sectional analysis (equations 3 and 4) as proxies for likelihood of financial statements fraud. The third variable of the industry specialization is tested in equation 5 of our sensitivity analysis. 10 The 21 reported scandals in alphabetical order are: Adelphia, AOL Time Warner, Bristol-Myers Squibb, CMS Energy, Duke Energy, Dynegg, El Paso, Enron, Global Crossing, Halliburton, Homestore.com, Kmart, Merck, Mirant, Nicor Energy LLC, Peregrine Systems, Qwest, Reliant Energy, Tyco, WorldCom, and Xerox. 18 (2001), we use the following model to compute abnormal returns for a portfolio of firms in the five industries: R pt 1 R Mt 2e De (5) where Rpt is the return from the portfolio of stocks in the selected industry p on day t, RMt is the return from the S&P 500 market portfolio, De is for indicator variables representing the legislative events, and is the error term. Each indicator variable takes a value of 1 on its event date t, one day before i.e. t-1, and one day after i.e. t+1. The indicator variable is set to 0 on other dates. The coefficient of β2e represents the average abnormal return of firms on event date i. Since all selected events occur in July 2002, we estimate equation (5) using daily-return data for 150 trading dates from April 1, 2002 to October 30, 2002. We calculate equation (5) for each of the five industries. VI - RESULTS Table 4 reports daily abnormal returns (ARs) and three-day cumulative abnormal returns (CARs) based on the constant-mean return model for the three-day period (t = -1, 0, and +1 relative to the announcement day) around each of the nine events using the returns on the S&P 500 value weighted index and the Value-line equally weighted index.11 The predicted signs on the abnormal returns are also reported. As indicated in Table 4 and consistent with Hypothesis 1, almost all events regarding the passage of the Act appear to have contained unanticipated and signaling news to the extent that they affected stock prices of publicly traded companies and could be detected by our model. Of the seven dates, for which we predict whether the event will increase or decrease the likelihood of passage of the Act, the sign of daily abnormal return 11 We also calculated 2-day CARs for days -1, 0 as well as 0, +1 for the S&P index. The results of 2-day CARs are similar to those of 3-day CARs. Thus, we only present results of 3-day CARs to capture both the possibility of the information leakage prior to the event date and the fact that the popular press (WSJ, NYT) reported the event typically one day after its announcement. 19 conform to our prediction for six dates. Abnormal return on July 19, 2002 is -3.78 percent, which is significant at 1 percent level. On this date, there were significant uncertainties regarding the form, content, and possibility of passage of the Act and thus, managers on the part of the House and the Senate met to possibly reconcile differences between the House bill and the Senate amendment. This event sent a signal to the market that the Act, in restoring investor confidence may not be forthcoming and therefore the market reacted negatively to this event. Abnormal return on July 24, 2002 is 5.78 percent, which is statistically significant at 1 percent level. On July 24, 2002 the Congressional Conference Committee reached an agreement on comprehensive reform legislation (the Act) and issued a conference report, which was perceived as an indication that the Act would be passed by Congress and signed into law by the president. The market viewed the conference report as signaling the increasing possibility of passage of the Act and reacted to this event positively. Results in Table 4 are based on the 121 day estimation period that started 142 days before our first event of February 14, 2002. As a robustness check we randomly chose 100 alternative benchmark periods of 120 days each in the preceding five years and found that the results in Table 4 are robust. The direction and statistical significance of the ARs and CARs are too sensitive to the specification of benchmark. The cumulative abnormal returns for the calendar time starting from the beginning of our sample events to the end are plotted in Figure 1. This Figure shows that the declining trend of the market was arrested and the market started moving up around the passage of the Act. Furthermore, the events with a decreasing probability of passage of the Act are associated with the market decline period whereas events with an increasing likelihood of passage are related to the market increasing period. 20 The examined nine events are associated with the likelihood of the passage of various provisions of the Act. These events are classified into three categories. The first group consists of two events (1 and 2) pertaining to the early introduction of two bills by the House and the Senate, which were considered either as hardly real institutional reform, difficult to implement, or controversial (Langevoort 2002). We detect negative but insignificant abnormal returns (both daily and 3-day cumulative) for these events, suggesting investors did not view these congressional bills as relevant or significant in addressing financial scandals. The second category consists of events (3 through 5) that either decreased the probability of the passage of the Act or provided information regarding difficulties in reaching agreements in the House and the Senate regarding the final provisions of the Act. We detected negative abnormal returns for these events as predicted, suggesting decreasing probability of the passage of the bill which would have positive impacts on corporate governance, the financial reporting process, and audit functions. We calculate total cumulative abnormal returns during the decreasing event period (July 15-July 19) for both the S&P 500 and value-line indexes. Total cumulative abnormal return for the S&P 500 index during the decreasing event period is -7.94 percent, with the t-statistic of -2.29, which is significant at 5 percent level. We search the WSJ and the NYT for these event dates (particularly July 15, 16, and 19) to find media reports on the likelihood of the passage of the Act and any confounding events that might have affected stock prices. The main reason for market decline during the announcement dates of these events as reported in the WSJ was concerns regarding the likelihood of passage of an effective Act in restoring already eroded investor confidence in the capital market. The Wall Street Journal reported on July 15, 2002 that even though the Senate will approve changes in accounting regulations, “the Senate bill won’t be complete unless it addresses stock options. This is the No. 21 1 post-Enron reform” (Murray 2002b). On July 16, 2002, the New York Times raised some doubt about “what form a final bill might take by the time it emerges from a conference committee” (Sanger and Oppel 2002). The New York Times reported on July 17, 2000 that Alan Greenspan, the Federal Reserve Chairman, blamed corporate greed as the cause of the breakdown in confidence among investors and advised House Republican leaders not to rush to legislate a bill which reflects how questions of business integrity are reshaping both politics and economic policy (Stevenson and Oppel 2002). The WSJ reported on July 19 that “Investors continued to suffer from an acute crisis of confidence regarding both Wall Street and corporate integrity. The thought of accounting irregularities still made investors flinch” (O’Brien 2002). Overall, these event announcements raised some doubt about the likelihood of the passage of the Act and its ultimate provisions and possible impacts. The progress on the passage of the Act was not encouraging and these events reduced the probability of its ultimate enactment. Investors viewed these events as bad news and the capital market reacted negatively to these events. The last group of events (6, 7, 8, and 9) unambiguously increased probability of the passage of the Act, and the market reacted positively to these events. Total cumulative abnormal return for this increasing event period (July 24-July 30) is +12.95 percent with t-statistic of +4.56 which is significant at 1 percent level. During July 24 to July 30 the House and Senate reached a compromise on legislation, and Congress passed the Act by a vote of 423-3 in the House and 990 in the Senate; the compromised bill was sent to the president to sign into law and eventually was enacted on July 30, 2002. We detected positive market reactions to these events suggesting that investors view provisions of the Act as beneficial to them and important in restoring public confidence in corporate governance, the financial reporting process, and audit functions. Our conclusion from Table 4 is that markets did react positively to the key events leading to the 22 passage of the Act. This suggests investors viewed the Act necessary to make corporations more accountable to them and thus benefited from its enactment. Results suggest that the Act improves investor confidence in the market at least in the short term. Our results are consistent with those of La Porta, et al. (1997, 1998) which suggest that better shareholder laws and their enforcement can significantly increase the willingness of investors to buy and own shares in listed corporations, which ultimately leads to higher valuations. Investor confidence is a complex issue depending on the perceived and actual risks and returns. However, there are several plausible explanations for the observed positive market reaction to the Act. First, despite characterization of the Act as either “far-reaching reforms” or “patchworks and codifications” of the existing requirements, it created news which was considered by investors as “good news”. Second, the Act might have been viewed by investors as value-increasing in the sense that it improves the probability of detection and prevention of corporate misconducts by increasing funding for more effective enforcement of Securities Laws, creating new criminal and civil liabilities for securities fraud, and imposing more severe penalties for wrongdoers. Third, the Act changed the auditors’ monitoring and disciplinary system from the perceived ineffective self-regulated environment to a more independent, regulatory framework under the SEC oversight function which was considered to be valueincreasing by investors. Fourth, the Act provides several measures that reduce management authority and control over audit functions by requiring the audit committee to be responsible for hiring, firing, retaining, compensating, and overseeing the work of auditors and making it unlawful to mislead auditors. This change in the balance of power between management and the board of directors, which traditionally has favored management, was viewed by investors as value-increasing. Finally, the Act directs the SEC and the Comptroller General to conduct 23 several studies (e.g., audit industry consolidation, mandatory audit firm rotation, investment banks and financial reports, rating agencies, off-balance sheet transactions, aiding and abetting) aimed at improving corporate governance, financial reporting, and audit functions. Investors might have considered the directions of these studies and their potential improvements as valueincreasing primarily because of the indication of continuous and direct congressional oversight of corporate America. We now shift our focus to the four events with positive market reactions as identified in Table 4 and discussed in the previous paragraphs (events 6, 7, 8, and 9). For these event dates, we run the regressions specified in equations (3) and (4). The results for the regression are presented in Table 5. The R-square for abnormal return equation is 3.89 percent and for cumulative abnormal returns is 15.01 percent. The regression suggests that bigger firms experienced a higher abnormal return. This is because the focus of the Act has been on the large high profile conglomerates. Higher earnings to price ratio has resulted in higher abnormal returns. Stock price volatility has a negative and statistically significant co-efficient, which goes against our hypothesis. The other variables such as market to book ratio, debt to capital ratio, auditor brand name, auditor opinion, and earnings restatements have not passed the test of statistical significance. Overall, the results appear to suggest that firms with greater scope for earnings misrepresentation due to size or low dividend payout ratios experienced the biggest impact of the Act. We separately analyzed the impact of the Act for five industries. Any negative stock price impact of the Act on these industries would suggest that investors view the Act as bringing to limelight a more than normal level of irregularities in these industries. Alternatively, if the firms in these industries were positively affected by the Act, it could be viewed that investors’ 24 concerns about these industries will be mitigated, and therefore result in a positive market reaction. Table 6 shows abnormal returns for each of the five selected industries sampled separately. Results indicate that financial scandals were not limited to a handful of companies because investors perceived them to be an industry wide problem. Although investors in all industries viewed the Act positively and the market reacted positively, investors were skeptical about the two industries of petroleum and telecommunications, as we detected negative coefficients for them (see Table 6).12 CONCLUSION Market participants must trust the quality, integrity, reliability, and transparency of financial reports published by public corporations. Numerous earnings restatements and alleged financial statement fraud cases have eroded investor confidence in corporate America and its financial disclosures. Marketplace mechanisms do not always (as evidenced by recent business and accounting scandals) provide timely, reliable, and effective self-corrections. Thus, regulations are expected to create an environment which promotes strong marketplace integrity and investor trust in the quality and transparency of financial disclosures. The Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 came into force in July 2002 to restore the eroded public confidence in financial reports. The purposes of the Act are to improve corporate governance, protect investors by improving the quality and reliability of corporate disclosures, establish the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) to govern the accounting profession, enhance the standard setting process for accounting and auditing practices, improve SEC resources, and establish rules on obstruction of justice and penalties for fraud. The implementation of provisions of the Act is intended to restore public confidence in corporate America and its 12 The Big-Four financial scandals of Enron, WorldCom, Global Crossing, and Qwest, as previously discussed, are in these two industries. 25 financial reporting process. Thus, investors are expected to benefit from the Act and react positively to several events leading to the passage of the Act. This study examines capital market reactions to the events (Congressional actions) leading to the passage of the Act. We detected significantly negative abnormal returns around the events that decreased the probability of the passage of the Act. Alternatively, we find significantly positive abnormal returns around the events that increased the probability of the passage of the Act and the actual passage of the Act. Results of our time-series analysis indicate that the capital market reacted positively to the Act. This suggests that the Act is value relevant in boosting the market’s confidence in the corporate governance and accounting systems. This study also sheds light on the determinants of this price reaction using firm-specific variables. Firms with larger market capitalization, higher earnings to price ratio, and higher stock price volatility are affected more by the Act than compared to other firms. Results also reveal that the healthcare industry was more positively affected by the passage of the Act. Results suggest that the Act, by either generating news which was considered as good news by investors or creating an environment which promotes strong marketplace integrity, has served as a stimulus to encourage initiatives for rebuilding the public confidence in corporate America and its financial reporting process. Results also suggest that the capital markets function more efficiently when investors have confidence in the market, and it appears that new regulation (e.g., the Act) was needed to restore investor confidence in the wake of high profile corporate and accounting scandals. There are a few caveats to our study. First, provisions of the Act affect all publicly traded companies. We were neither able to classify affected firms into treatment versus control groups nor could we use the more popular market model to test stock price reactions to the Act. 26 Thus, we use the constant-mean return model to investigate the reaction of the entire market portfolio of firms in the S&P 500 and value-line indexes to the events leading to the passage of the Act. To the extent that there are confounding events or omitted variables which are also correlated with our events or cross-sectional model, it is possible that our analyses are being driven by these factors and not by provisions of the Act. However, this should not negate interest in our findings because confounding events and correlated and omitted variables remain an issue in all time series and cross-sectional studies. In addition, we searched the Wall Street Journal, the Wall Street Journal Index, and the New York Times to identify any confounding events that might have affected stock prices during June and July 2002 (see Table 4). We found that the Act, the likelihood of its passage, and its possible impacts on restoring the public’s confidence and prevention of future business and accounting scandals were dominating news during our test period and there were no other confounding events. Second, we investigate the possible immediate signaling effects of the Act on market participant’s confidence in the securities market and whether investors viewed the Act as valuerelevant and beneficial. Many provisions of the Act require the SEC and other regulators to establish rules to implement those provisions regarding corporate governance, financial reports, and audit functions. An interesting extension of our study would be to examine impacts of these implementation rules on corporate governance, the financial reporting process (management reporting conservatism), and audit functions (auditors’ reporting conservatism). In the shortterm, the Act created news which was considered by investors as “good news.” We leave the issue of whether, in the long term, the Act is capable of rebuilding public trust in corporate America and its financial reporting process to future research. 27 REFERENCES Ali, A., and S. Kallapur. 2001. Securities price consequences of the private securities litigation reform act of 1995 and related events. The Accounting Review 76 (July): 431-460. Benston, G.J. 1973. Required disclosure and the stock market: an evaluation of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. The American Economic Review 63.1 (March): 132-155. Bhattacharya, U., P. Groznik, and B. Haslem. 2002. Is CEO certification of earnings numbers value-relevant? Working paper, Indiana University. Binder, J. 1985. Measuring the effects of regulation with stock price data. Rand Journal of Economics 16 (2): 167-183. Brown, S.J., and J.B. Warner. 1985. Using daily stock returns: the case of event studies. Journal of Financial Economics (14): 3-31. Bumiller, E. 2002. Bush bill aimed at fraud in corporations. The New York Times (July 31). Campbell, J.Y., A.W. Lo, and A.C. Mackinlay. 1997. The econometrics of financial markets. Princeton: Princeton University Press, Chapter 4. Chow, C.W. 1983. The impacts of accounting regulation on bondholder and shareholder wealth: the case of the securities acts. The Accounting Review (July): 485-520. Chow, C.W. 1984. Financial disclosure regulation and indirect economic consequences: an analysis of the sales disclosure requirement of the 1934 securities and exchange act. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting 11 (Winter): 469-483. Cornett, M.M., Z. Rezaee, and H. Tehranian. 1996. An investigation of capital market reactions to pronouncements on fair value accounting. Journal of Accounting & Economics 22: 119-154. Cotton, D.L. 2002. Fixing CPA ethics can be an inside job. The Washington Post (October 20): BO2. Cunningham, L.A. 2003. The Sarbanes-Oxley yawn: heavy rhetoric, light reform (and it might just work). Forthcoming, University of Connecticut Law Review, vol. 36. Easton, P.D. 1999. Security returns and the value-relevance of accounting data. Accounting Horizons 4 (December): 399-412. Espahbodi, H., P. Espahbodi, Z. Rezaee, and H. Tehranian. 2002. Stock price reaction and value-relevance of recognition vs. disclosure: the case of stock-based compensation. Journal of Accounting and Economics (August): 343-373. Forbes. 2002. The corporate scandal sheet. Available at http://www.forbes.com/home/2002/07/25/accountingtracker.html. Goyal, A., and P. Santa-Clara. 2002. Idiosyncratic risk matters. Journal of Finance, forthcoming. Ingram, R.W., and E.G. Chewning. 1983. The effect of financial disclosure regulation on security market behavior. The Accounting Review (July): 562-580. 28 Institute of Internal Auditors (IIA). 2002. Research brief: CEO and CFO certifications to SEC company response and the internal auditor’s role. (July 26) available at http://www.gain2.org/ceosample.doc. Johnson, M., R. Kasznik, and K. Nelson. 2000. Shareholder wealth effects of the private securities litigation reform act of 1995. Review of Accounting Studies (513): 217-233. Karpoff, J., and P. Malatesta. 1989. The wealth effects of second-generation state takeover legislation. Journal of Financial Economics 25 (2): 291-322. Langevoort, D.C. 2002. Managing the ‘expectations gap’ in investor protection: the SEC and the post-Enron reform agenda. Working paper, Georgetown University Law Center. La Porta, R., F. Lopez-de-Silanes, A. Shleifer, and R. Vishny. 1997. Legal Determinants of External Finance. Journal of Finance 52: 1131-1150. La Porta, R., F. Lopez-de-Silanes, A. Shleifer, and R. Vishny. 1998. Law and finance. Journal of Political Economy 106: 1113-1155. Levitt, A. 1988. SEC Chairman from the Speech. The numbers game. NYU Center for Law and Business (September), Available at http://www.sec.gov. Levitt, A. 2002. CFOs and financial executives favor more, not less regulations. Today’s News, Available at http://www.bfmag.com/Levitt. Makinson-Cowell. 2002. US institutional investors give securities reforms mixed reviews. Available at http://www.makinson-cowell.co.uk/about_us/press%20please%wjj.pdf. Murray, S.D. 2002a. Is SEC ready for its own sweeping changes? New York Law Journal (August 29). Murray, S.D. 2002b. Senate faces stock-option issue in accounting bill. The Wall Street Journal (July 15): C4. O'Brien R. 2002. So much for up, as stocks fall: Siebel Systems, Kraft decline. The Wall Street Journal (July 19): C3. Osterland, A. 2002. No more mr. nice guy: a CFO survey suggests that recently passed rules for auditors may be a wise idea. CFO Magazine (September 1), available at http://www.cfo.com/printarticle/0,5317,7614|,00.html. Rezaee, Z. 1990. Capital market reactions to accounting policy deliberations: an empirical study of accounting for foreign currency translation 1974-1982. Journal of Business Finance and Accounting 17 (Winter): 635-648. Rezaee, Z. 2002. Financial statement fraud: prevention and detection. John Wiley & Sons, New York, N.Y. Ribstein, L.E. 2002. Market vs. regulatory responses to corporate fraud: a critique of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002. Working paper (September), University of Illinois College of Law, available at http://ssrn.com/abstractid=332681. Sanger, D.E., and R.A. Oppel. 2002. Senate approves a broad overhaul of business laws: tougher than house bill. The New York Times (July 16): D8. 29 Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002. The Public Company Accounting Reform and Investor Protection Act. Available at http://www.whitehouse.gov/infocus/corporateresponisbility. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). 2002. Sworn statements pursuant to section 21(a)(1) of the SEC Act of 1934, File No. 4-460, June 27. Available at http://www.sec.gov/rules/other/4-460.htm. Sorin, D.J., K.K. Pappa, and E. Ragosa. 2002. Sarbanes-Oxley Act: politics or reform? Statut’s effects are not as profound as legislators would have us believe. New Jersey Law Journal (September 2). Spiess, K., and P. Tkac. 1997. The private securities litigation reform act of 1995: the stock market casts its vote. Managerial and Decision Economics 18 (7-8): 545-561. Stevenson, R.W., and R.A. Oppel. 2002. Fed chief blames corporate greed: house revises bill. The New York Times (July 17): A1, 5. Stice, E.K. 1991. The market reaction to 10-K and 10-Q filings and to subsequent the Wall Street Journal earnings announcements. The Accounting Review 66 (January): 42-55. 30 CARs -0.05 Aug-27-02 Aug-22-02 Aug-19-02 Aug-14-02 Aug-09-02 Aug-06-02 Aug-01-02 Jul-29-02 Jul-24-02 Jul-19-02 Jul-16-02 Jul-11-02 Jul-08-02 Jul-02-02 Jun-27-02 Jun-24-02 Jun-19-02 Jun-14-02 Jun-11-02 Jun-06-02 Jun-03-02 May-29-02 May-23-02 May-20-02 May-15-02 May-10-02 May-07-02 May-02-02 Apr-29-02 Apr-24-02 Apr-19-02 Apr-16-02 Apr-11-02 Apr-08-02 Apr-03-02 Mar-28-02 Mar-25-02 Mar-20-02 Mar-15-02 Mar-12-02 Mar-07-02 Mar-04-02 Feb-27-02 Feb-22-02 Feb-19-02 Feb-13-02 FIGURE 1 CUMULATIVE ABNORMAL RETURNS (CAR) FROM FEBRUARY 1, 2002 TO NOVEMBER 19, 2002 a CAR 0.1 0.05 0 Increasing Events -0.1 -0.15 Decreasing Events -0.2 -0.25 -0.3 Calendar Dates a. Cumulative abnormal returns for S&P 500 in calendar time. (These are not the 3-day cumulative return) For instance, cumulative return for February 28 is the sum of abnormal returns from February 1 to February 28. 31 TABLE 1 CHRONOLOGICAL EVENTS LEADING TO THE PASSAGE OF THE SARBANES-OXLEY ACT OF 2002 EVENT # DATE EVENT DESCRIPTION 1 February 14, 2002 Introduction of H.R. 3763 The House of Representatives (Oxley, the Committee on Financial Services) introduced H.R. 3763 to protect investors by improving the accuracy and reliability of corporate disclosures made pursuant to the Securities Laws. 2 June 25, 2002 Introduction of S. 2673 Senator Sarbanes introduced S.2673 (similar to S. 2004) to (1) improve the quality and transparency in financial reporting; (2) designate an independent Public Accounting Board; (3) enhance the standard setting process for accounting practices; and (4) improve SEC resources and oversight. 3 July 15, 2002 Passage of S.2673 The Senate passed S. 2673, the Public Company Accounting Reform and Investor Protection Act of 2002. 4 July 16, 2002 Passage of H.R. 3763 The House passed H.R. 3763, the Public Company Accounting Reform and Investor Protection Act of 2002. 5 July 19, 2002 Conference Committee Meeting There were some uncertainties regarding the form, content, and the possibility of passage of the Act. Thus, the managers on the part of the House and the Senate met to reconcile the differences between the House bill and the Senate amendment. 6 July 24, 2002 Conference Report The Congressional Conference Committee reached an agreement on comprehensive reform legislation (the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002). 7 July 25, 2002 Congressional Legislation 8 July 26, 2002 Compromised Bill Sent to the President Congress sent a compromised bill to the President to sign into law. 9 July 30, 2002 Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 President Bush signed into law the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002. Congress passed the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 by a vote of 423-3 in the House and 99-0 in Senate. 32 TABLE 2 DEFINITIONS OF VARIABLES USED IN THE CROSS-SECTIONAL ANALYSIS AND DATA SOURCES Variables Definition Data Source 1. Dependent Variables: AR CAR Daily abnormal returns (AR) calculated for events 6, 7, 8, and 9. Equation 1: www.finance.yahoo.com Three-day cumulative abnormal returns (CAR) calculated for events 6, 7, 8, and 9. Equation 2: www.finance.yahoo.com 2. Independent Variables: Firm Size (Mcap) Market capitalization of the firm calculated as the market value of the equity at the end of June 2002. Market to Book Ratio Market to book ratio of total assets at the end of June 2002. (MB) Earnings to Price Ratio (EP) COMPUSTAT COMPUSTAT Earnings to price ratio of the firm in June 2002. COMPUSTAT Income before extraordinary items minus cash dividends divided by income before extraordinary items calculated for the quarter ended June 2002. COMPUSTAT Debt to capital ratio calculated for the year ended December 2001. COMPUSTAT A dummy variable coded 1 if Arthur Andersen was the auditor, 0 otherwise. COMPUSTAT A dummy variable coded 1 if the auditor’s opinion was unqualified for the year ended December 2001, 0 otherwise. COMPUSTAT Volatility ( ) A proxy for the firm’s idiosyncratic risk calculated as the standard deviation of monthly stock price changes during the last 60 months starting July 1997 and ending June 2002. COMPUSTAT Financial Restatements (Restate) A dummy variable coded 1 if the firm has voluntary, auditor recommended, or SEC enforced financial restatement(s) during 1995-2002, 0 otherwise. The Dow Jones Interactive and Lexis-Nexus information services Earnings Retention Rate (Q) Debt to Capital Ratio (DTC) Auditor (Audit AA) Opinion (Opn) 33 TABLE 3 DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICS AND CORRELATIONS FOR REGRESSION VARIABLES Panel A: Descriptive Statistics Abnormal returns Cumulative abnormal returns Market capitalization Market to book ratio Earnings to price ratio Earnings retention ratio Debt to capital ratio Auditor is Arthur Andersen Qualified audit Stock price volatility Earnings Restatement Abbreviation AR CAR Mcap MB EP Q DTC AuditAA Opn σ restate Standard Mean Deviation 0.0004 0.0548 -0.0082 0.1210 0.0180 0.0348 0.0354 0.1171 0.0010 0.2184 0.8013 0.7979 0.4518 3.2558 0.1608 0.3674 0.6243 0.4844 10.5279 7.1207 0.0374 0.1897 Minimum Maximum -0.4742 0.6300 -1.3868 1.5492 0.0005 0.2962 -1.5796 1.4176 -2.9096 0.6712 -3.9491 8.8333 -73.1707 5.1440 0 1 0 1 1.4639 71.6531 0 1 Panel B: Pearson Correlation Coefficientsa Mcap Mcap MB Q DTC σ 1 0.05 0.021 2124 -0.043 0.066 1788 0.034 0.122 2124 0.022 0.302 2128 2128 MB Q DTC σ restate AuditAA Opn EP -0.069 0.001 2128 0.068 0.002 2108 0.014 0.117 0.51 <.0001 2136 2136 0.038 0.08 2116 -0.081 2E-04 2128 -0.043 0.066 1788 -0.031 0.186 1796 1800 0.034 0.129 0.122 <.0001 2124 2132 -0.013 0.594 1800 2136 0.001 0.104 0.948 <.0001 2136 1800 -0.004 0.867 2136 2140 0.014 0.529 2136 0.025 0.24 2140 2140 0.015 -0.097 0.5 <.0001 2136 2140 -0.059 0.006 2140 2140 0.018 0.457 1800 -0.069 0.098 -0.132 0.001 <.0001 <.0001 2136 2140 2140 0.003 0.88 2140 2140 -0.04 0.093 1780 0.013 -0.325 -0.13 0.553 <.0001 <.0001 2116 2120 2120 0.025 0.249 2120 0.03 0.168 2120 -0.081 2E-04 2128 0.006 0.791 1800 0.014 -0.109 0.51 <.0001 2136 1800 -0.069 0.117 0.001 <.0001 2128 2136 0.068 0.002 2108 1 0.038 0.08 2116 0.001 -0.148 0.948 <.0001 2136 2136 EP 2136 -0.032 -0.148 0.14 <.0001 2128 2136 -0.031 0.129 0.186 <.0001 1796 2132 -0.032 0.14 2128 Opn 0.05 0.021 2124 0.022 0.302 2128 1 restate AuditAA -0.013 0.104 0.594 <.0001 1800 1800 1 -0.004 0.867 2136 1 0.006 -0.109 0.791 <.0001 1800 1800 0.014 0.529 2136 0.015 0.5 2136 0.018 0.457 1800 -0.04 0.093 1780 -0.069 0.001 2136 0.013 0.553 2116 0.025 -0.097 0.098 -0.325 0.24 <.0001 <.0001 <.0001 2140 2140 2140 2120 1 -0.059 -0.132 -0.13 0.006 <.0001 <.0001 2140 2140 2120 1 0.003 0.88 2140 0.025 0.249 2120 1 0.03 0.168 2120 1 2120 a The correlation for each pair of variables is presented in the first row. The second row is the p- value and the third row is the number of observation for which data is available for both variables. 34 TABLE 4 MARKET REACTION TO THE EVENTS LEADING TO THE PASSAGE OF THE SARBANES-OXLEY ACT OF 2002 S&P 500 Index b Event Daily Abnormal Return 3-day CARd Value-line Index c Event Day Abnormal Return Event Number Event Date Predictiona 3-day CARd 1 Feb-14-02 U -0.13% -0.13% -0.76% -0.39% 2 Jun-25-02 U -1.62% -1.42% -1.66% -2.30% 3 Jul-15-02 D -0.32% -2.72%* -0.85% -2.27% 4 Jul-16-02 D -1.80% -1.50% -0.88% -1.34% 5 Jul-19-02 D -3.78%** -9.67%** -3.11%* -8.19%** 6 Jul-24-02 I 5.78%** 2.62%* 4.34%** -0.20% 7 Jul-25-02 I -0.51% 7.01%** -0.80% 4.21%** 8 Jul-26-02 I 1.74% 6.69%** 0.67% 5.34%** 9 Jul-30-02 I 0.48% 6.97%** 0.28% 4.63%** Notes: ** and * indicate statistical significance at 1% and 5% levels respectively a. Predictions: Increase (I), decrease (D), or uncertainty (U) in the likelihood of the passage of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 b. Abnormal returns are calculated using the return on the S&P 500 value weighted index in a constant-mean return model. c. Abnormal returns are calculated using the return on the Value-Line equally weighted index in a constant-mean return model. d. CARs are sum of ARs on days -1, 0, and +1. Results for 2-day CARs for days (-1, 0) and (0, +1) are not statistically different from those of 3-day CARs. 35 TABLE 5 CROSS SECTIONAL ANALYSIS OF ABNORMAL RETURNS SURROUNDING THE KEY EVENTS LEADING TO THE PASSAGE OF THE SARBANES-OXLEY ACT OF 2002 a CARit 1 MCapi 2 MBi 3 EPi 4 Qi 5 DTC 6 AuditAA 7 Opn 8 9 Restate Dependent Variable AR N= 1668 Explanatory Variables Intercept Market capitalization Market to book ratio Earnings to price ratio Earnings retention ratio Debt to capital ratio Auditor is Andersen Qualified audit Stock price volatility Earnings Restatement Adjusted R-square Coefficient 0.0024 0.0740* 0.0052 0.0187** 0.0030 0.0020 0.0034 0.0004 -0.0010** 0.0019 3.89% Standard error 0.0034 0.0321 0.0093 0.0053 0.0016 0.0022 0.0033 0.0026 0.0002 0.0062 CAR Standard Coefficient error 0.0276** 0.1444* 0.0226 0.0673** 0.0034 0.0057 0.0093 -0.0014 -0.0043** -0.0234 0.0070 0.0666 0.0193 0.0111 0.0034 0.0046 0.0069 0.0054 0.0003 0.0128 15.01% Notes: ** and * indicate statistical significance at 1% and 5% levels respectively a. This table estimates two regressions with abnormal return (AR) and cumulative abnormal returns (CAR) respectively. The equation for CAR is shown above and AR equation is similar. 36 TABLE 6 STOCK RETURN REGRESSIONS FOR THE SELECTED INDUSTRIES a R pt 1 RMt 2 e De Industry First-five digits of NAICS Event Description Passed by Congress Adjusted R-Square Independent Variable/ Event Date Intercept Market 7/25/2002 Electric Power Generation Natural Gas Distribution Pharmaceutical Preparation Manufacturing 22111 22121 32541 Coefficient Coefficient Coefficient Petroleum and Petroleum Products Wholesalers Wired Telecommunications Carriers 42272 Coefficient 51331 Coefficient 0.0072** 0.8262** 0.0150 0.0000 0.7427** 0.0132 -0.0002 0.9283** 0.0161* -0.0023 2.7520** -0.1046* 0.0016 1.1751** -0.0355** 0.3454 0.473 0.6997 0.2748 0.4755 Notes: Coefficients are marked with ** and * if they are significant at 1% and 5% levels respectively. a. OLS estimates reported in this Table are based on CARs for each industry portfolio as dependent variable and the market return and the passage of the Act as explanatory variables. We run the OLS regressions for AR for each of the event dates and observed statistically similar results. 37 APPENDIX Summary of Some Provisions of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 1. Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) The Act creates a new public company accounting oversight board (PCAOB) which is empowered to set auditing, quality control, and independence and ethics standards as rules. The PCAOB is an independent not-for-profit organization subject to SEC oversight, made up of five members of which no more than two may hold the CPA credential. The PCAOB registers public accounting firms that conduct audits of publicly traded companies, conducts inspection of the registered public accounting firms and performs investigations and discipline proceedings. 2. Auditor Independence The registered public accounting firms will be prohibited from providing several non-audit services to their clients contemporaneously with the audit and the lead audit or coordinating partner and the reviewing partner must rotate off of the audit every five years. 3. Corporate Responsibility The Act requires that each member of the audit committee be independent members of the board of directors, have the authority to engage independent counsel and other advisors, and be directly responsible for the appointment, compensation, and oversight of the work of any registered public accounting firms. 4. Enhanced Financial Disclosure The Act creates significant reporting responsibilities for top executives of publicly traded companies to improve financial disclosures including certification of financial reports by the CEOs and CFOs and establishment of adequate and effective disclosure controls and procedures. 5. Trading, Disclosure, and Conflicts of Interest The Act prohibits insider trades during pension fund blackout periods, requires disclosure of all off-balance sheet transactions, and prevents investment banking staff from supervising research analysts. 6. Corporate Misconduct and Crime The Act contains several provisions to prevent wrongdoing and establishes a new crime of securities fraud with a tough 25-year jail sentence 7. Further Studies The Act directs the SEC and Comptroller General to conduct nine studies on various aspects of corporate governance, the financial reporting process, audit functions, investment banking, and enforcement actions of corporate laws. 38