Vittoria Marino, Giada Manolfi, Debora Tortora, Paola Zoccoli

advertisement

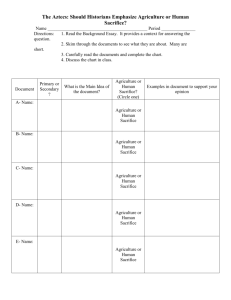

EXPERIENCE COMMUNICATION, VIRTUAL COMMUNITY AND VALUE CREATION IN ON LINE BUSINESS Vittoria Marino – Associated professor in International Marketing - University of Salerno Italy vmarino@unisa.it Giada Mainolfi - Contract researcher in Business Administration - University of Salerno Italy gmainolfi@unisa.it Debora Tortora - Phd in Communication Sciences - University of Salerno - Italy dtortora@unisa.it Paola Zoccoli - Phd in Public Management - University of Salerno – Italy pzoccoli@unisa.it Though being the result of shared considerations by the searchers, the work sections have been dealt with as follows: par. 1 by Vittoria Marino, par. 2 by Debora Tortora, par. 3 by Giada Mainolfi, par. 4 and 5 by Paola Zoccoli. EXPERIENCE COMMUNICATION, VIRTUAL COMMUNITY AND VALUE CREATION IN ON LINE BUSINESS 1.Foreword; 2. Marketing and communication in the experience economy; 3. Experience space in on line business: the community role; 4. Virtual community contribution to the value creation of the firm; 5.Conclusions; Select Bibliography Abstract Accelerating the replacement of satisfactory objects and the emergent socializing vs cocurrent subjectiveness of consumption lead to qualify and valorize the space of existence and the “area of living” through situations in which the customer can experience affective and emotional states associated with consumption. In this context firms have been engaged in the correct creation and communication of real situations. The first section of the paper provides background information on the development of marketing studies up to "experience economy”. Then opportunities for on line business are discussed offered by means of a virtual community, creating a value system for the consumer from which a sustainable advantage for the firm is derived. 1. FOREWORD The acceleration in replacing objects, the transitory pleasure of possessing, but also an exquisitely democratic dimension of the self social expression - thanks to a more autonomous and personal access to lifestyles that are no longer expression of class belonging, but refer to individualized dimensions - lead today to a different meaning of the concept of “consumption”. The action of consumption, no more only a sphere of activities like other functions carried out by the individual, is qualified as “a cultural sphere, capable to produce its own view of the world, a system of values and a structure of peculiar personalities” (Siri G., 2001), expressing a new “area of living”, appealing to principles of plurality and social mutability. If the whole existence of modern man is characterized by “search”, his aware and voluntary participation into manifold projects sets itself as a necessary preliminary basis for the “social construction of one’s identity” (Di Nallo E., 1998). Sharing this process, the customer is necessarily recognized as a scant, and, consequently, precious and yearned for resource, becoming the focus of a new policy of appreciation of the individual, in the pursuit of the individual expectations that outline a “unique person”. Therefore, the firm needs to be cast into a new dimension, basically a project one, in which its own market interlocutors appear to be, above all, “people and their dreams”. In fact, if a firm is viable when proposing new renewed values, in order to achieve consonance with its demand (consumers’ requirements), the customer himself and his consumption ritual become the ultimate element of the firm changing process. A reconsideration, in an interactive key, of the relations with the customer system becomes thus necessary; in fact a satisfied customer (though with all his different ways of expressions) is the necessary starting point to have a loyal customer, representing the real patrimony, perhaps the most precious one, on which every business sets its opportunities of development and bases its actual survival. Consequently, if for a long time the success of online marketing has expressed itself through the profitable combination of the ideas of convenience and practicality of the economic relation in order to stop the customer and tie him to the firm web site, on the contrary, the contemporary trend goes toward an organization capable to communicate with the customer through emotions, involving him in the purchase, making him feel a protagonist in his choice and satisfied with it. On the other hand emotion contributes to solve the issue of how to arrange knowledge and actions, within a context that the navigator (as well as the firm) can never totally know and in which he is meant to act with limited resources. The future of marketing, especially of web marketing, starts from these background evaluations. 2 2. MARKETING AND COMMUNICATION IN THE EXPERIENCE ECONOMY If we analyze the physiological evolution of online markets, we can observe a progressive saturation of the demand for products and services. At the same time we can notice another typology of demand, in which the primary needs of the cyberconsumer are replaced by others connected to time - as a fruition moment to be valorised as a scant resource - and to the emotional sphere - characterizing itself as a search for sense and identity in the supply and in the navigation action itself. Consumption, as “narrative development”, capable to express new meanings in the interaction between the supply and the way it is perceived by the consumer, leads necessarily to such an analysis. On the other hand, “consumption innovation” refers to a search for novelty as a virtual use of consumption situations or different contexts, outlining how the motivations underlying certain navigation and, consequently, purchasing processes, involve considerably different clusters of customers, according to the consumer perspective, such as efficiency, game dimension, excellence, aesthetics, status, ethics, esteem, spirituality. The concept of experience consumption, as a particular condition of on and off line marketing research, is emerging just in this field, even if with alternate tension in time. Understanding the phenomenon referring to the experience dimension, however, has a sense under a previous analysis of the interpretations of the idea of experience brought about in different scientific fields: as activity (or passivity, meant as absence of action) producing a modification, in terms of growth of knowledge, in the subject involved (Carù A., Cova B., 2003). Therefore, if the conceptual matrix, outlined by experimental science, qualifies the notion of experience as a function of the reproducibility of the observed phenomena, these being based on objective and generalizable data (1), on the contrary, philosophical studies safeguard the individual/personal dimension, producing not universal knowledge but knowledge belonging to a single actor. Similarly, the sociological and psychological approaches to this issue emphasize the individual cognitive dimension of experiential activity through which human beings build up their own identity. All this leads to the interpretation, supported here, of the category of experience as personal real life, though caused by external stimuli, controllable by the firm and often loaded with emotions. Thus views of sure interest in the tradition of management and business studies get started. On the other hand, without going over all the studies on consumer behaviour again, already in the early Eighties the issue of the consumer as a not perfectly rational entity, unlike the way economic sciences had pointed out, had emerged attracting the attention of these kinds of analysis. The so-called utilitarian studies have as its object of study the consumer decisional problem in front of getting supplies and, consequently, of picking up different goods. They solve the question proposing a perfectly rational customer choosing the offer that provides the highest utility – or likely to do so – on the basis of its characteristics. The hedonistic thought, instead, following the view of the "consumer as an experiential being that buys for fun (Vescovi T., Checchinato F., 2003), recovers the role of emotions as meaningful consumption experiences, not only connected to hedonic assets (Addis M., 2002), as at the beginning, but also linked to daily consumption supplies (figure 1). From this moment on, consumption starts to be conceived as a holistic experience, both by the customer - that judges the performance on the basis of the involvement and the general value he receives, not only in terms of price/quality relation of the supply (2) - and by the firm, required to plan events, situations, real life contexts and not simply products. In fact “consumption is an experience coming out of the interaction between a subject – the consumer – and an object – a product, an event, an idea, a person, a place, or any other thing within a given context” (Addis M., 2002). In such a perspective experience becomes a new form of purchasing, like a suspension between need and desire (Bucchetti V., 2004). In Rifkin’s words: “in the age of material capitalism and property the emphasis was on assets and services sale; in the cyberspace economy, the transformation of assets and services into goods becomes secondary compared to the reification of human relations. In a more and more frenetic and changeable network economy to keep customer attention high means to succeed to control most of their time. Moving from moderate market transactions, limited in time and space, to relations/goods unlimited in time, the new economic sphere is able to subdue a wider part of daily life to profit” (Rifkin J., 2000). This is the real essence of the modern supply system, in which the customer oriented perspective ends up to prevail 3 on the production system itself, developing in terms of “access to the customer” and willing to establish lasting relations (not only commercial) with him (3). At this point the challenge, especially when referred to electronic interactions, is set more and more as a matter of relations (and control) of the consumers community. The aim of the firm, both as a click and mortar and as a click and click kind - from production to sale, to the management of long term relations – becomes more and more to create value (not only economic one) for the customer, grouped within individualized micro personal clusters, almost as if every single individual is considered as a unique and special fragment of a society searching for unusual socializing and aggregating patterns. Just these relations and formulas of aggregation seem to represent the present emerging, critic requirement of the consumption system, whose defence, then, ensures the competitive advantage aimed at. Thus the firms that succeed in this aim reap the fruits of their capacity to appeal to a common and reciprocal feeling of understanding, apt to put back together these fragments into “tribal” unities, urban sub groups, expressing life rules (emotional) to which the product/service already belongs. This is the essence of tribal marketing (Lasalle D., Britton T. A., 2003) that can put together rituals and phenomena of emotional “polysensorial” collective consumption, thus determining the connection values of the fragment/ subgroup. “[the firm] will communicate to fragment/ subgroups, to neo tribes, through devoted media thanks to a new sociological structure of its intelligence database […] This will happen without ever pushing the purchase or for a utilitarian purpose aimed at selling, thus showing real empathy and tribal sympathy. In the future the brand will share collective backgrounds, hobbies and tendencies as an involved observer, sharing the socio-antropological “affective ties” of the new-tribes, just making it known it was there as well. Within the tribe fragment an authentic totemic role will be played by opinion leaders. Testimonials, in other words ‹whitch doctors››, will be the aruspices of the bribal phenomenon, capable of starting the clapper board for a new scene: the passage from customers to costum-actors” (Alvisi M., 2004). Values are recognized in four main components, originating a shared common sense: sense of belonging, as the awareness to be part of a neo-tribe, allows group members to experience a feeling of emotional, affective, physical, economic safety and of identification with the micro-group, with which to share an exclusive symbolic system; influence, reciprocal and bi-directional, of the individuals on the group and of the tribe on individuals; integration and the needs satisfaction coming from belonging to a specific community (4); finally, shared emotional connection, that is the availability of a common story, possibly shared between group members, that increases group cohesion through events, rituals, repeated and shared positive experiences. All that is highly claimed in virtual communities. Emerging neo tribes, namely consumer communities, on the one hand and the opportunity of relation with them, using a shared value-symbolic register, on the other hand, allow to try out relational nets supporting transactions between firms and consumers. In other words, there is a new situation, with a high informative, emotional and sensory content, that allows the “tribal” consumer, or the cyber consumer, to enjoy real events and experiences, these becoming themselves an object of interest. The relation with the firm is built well beyond a mere mediation between the parts, being based, above all, on “generative communication”, whose aim is “to generate”, to produce and to spread sense, identity, sharing of purposes, through the activation of emotional alarms, capable to give meaning to such enunciative activity. Within marketing communication, incorporating emotions has a key function, leading the individual narrative process first, and the collective one on a second relational stage, towards perception of the experience. In order to convey the ready-made experience correctly, if communicative processes strongly direct and influence the consumption system they sponsor (and they are set in), the system gives shape and substance to the communication processes themselves, that ensure visibility and expression. Such interdependence develops a spiral pattern showing the two dimensions in continuous progress with ever different and innovative forms. In other words, consumption experience succeeds in becoming an appreciable economic proposal of value if the capability to do stands side by side with the capability to make it known (5), that is to make it visible outside (Siano A., 2001). In other words, consumption experience has its substance in the degree of communication it assumes to take shape. Experience, in fact, shows and feeds in itself a strong communicative need, that supports its vitality with the opportunity to be recognized by the customer and be endowed with value. All this states the need of communication of the experience. 4 On the side of communicative needs it is possible to observe, above all, an alteration of the space-temporal structure of the consumption routine. Together with this, the productive critical role of consumption so far described and the renewed centrality of the communicative agreement between consumption and its elaboration re-consider the theoretical and practical interpretative pattern used in firm communication up to now. Experience, therefore, individuates in the action itself (that is in its being carried out and reproduced) its own medium, the channel/ means to connect itself to the external world, thus creating its own space of influence, namely the consumer community using it. The absolute necessity of communication, therefore, appears to be a decisive intangible factor for the survival and development of an experience producing firm, provided that the communication need is a faithful representation of the inspiring values of the system. The hypothesis supported here gives an interpretation of the concept of experience that doesn’t only limit its field of action to a dramatization of the event performed, intentionally made spectacular by the firm (Pine J. B. Gilmore J. H., 2000) – also following a cognitive model that is self-portrayed in the consumer/navigator’s mind, given certain expectations, whose form is clearly defined while being put into action - but is related to the context (portal, firm web site etc.) in which the event is lived and to what has been previously known from business interactions. With regard to this, we can justify the trend inversion according to which the orientation to the image (by the firm offering experience proposals), meant as mere appearance coming out of an advertising formula with limited action in time and effects - is replaced by orientation to transparency in firm business communication. So, firm communication is transparent when, conveying its own corporate identity, allows superior systems to perceive the underlying corporate personality. This aims at reaching a balance between corporate identity (as the whole of the visual elements of the system organization) and corporate image (the way communication is perceived by the external audience at a given time). The codification of experience, seen as a commercial offer or, at least, as an integrant part of it, gets its features first of all from institutional (traditional) communication strategy. This carries out the conversion process from corporate identity into corporate image (Ferraro G., 1998) through a clear expression of the competence of the firm, what it is, its corporate personality (6). What has been fundamentally noticed is that the customer no longer falls within a generic definition of public, passively assisting to a show performed by the firm. In fact the value of the experience is recognized to be just in the customer/ navigator’s involvement in the show. As a consequence, in order to be realized in its experiential form, the performance must be able to originate an interaction, if not physical, at least emotional, with its user. That is to be able to cause a modification in him. These are the bases the value model is essentially built on. In fact “We have all experienced times when, instead of being buffeted by anonymous forces, we do feel in control of our actions, masters of our own fate. On the rare occasions that it happens, we feel a sense of exhilaration, a deep sense of enjoyment that is long cherished and that becomes a landmark in memory for what life should be like. This is what we mean by optimal experience” (Csikszentmihalyi M., 1990). In the consumer perspective, therefore, customer experience as a rewarding human expression, is experienced when the psychic energy involved is carried on not only as high emotional involvement but also as control of the situation (Mathwick C., Rigdon E., 2004). In literature it is referred to as “flow experience”. Taking as reference points two dimensions, that is the grade of ability the situation requires, and the grade of challenge perceived by the user, namely the psychic energy involved, it is possible to go through alternative experiences, depending on whether the user perceives a limited energy to be applied in front of little involving (in which case a sense of bore and apathy will be felt) or more involving competitions (which will produce a feeling of worry, anxiety and excitement). The increasing capacity level will lead to a relaxing feeling first, and then a sense of control with increasing challenge level, up to the flow experience, in which both dimensions are active. Of course these kinds of experiences are not lived in the same way by all customers, the point of view being typically subjective and so individual. Therefore, “Contrary to expectation, «flow» usually happens not during relaxing moments of leisure and entertainment, but rather when we are actively involved in a difficult enterprise, in a task that stretches our mental and physical abilities. Any activity can do it. Working on a challenging job, riding the crest of a tremendous wave, and teaching one’s child the letters of the alphabet are the kinds of experiences that focus our 5 whole being in a harmonious rush of energy, and lift us out of the anxieties and boredom that characterize so much of everyday life” (Csikszentmihalyi M., 1990). In our opinion, however, “flow experience” does not necessarily qualify a category of events connected to extraordinary modifications of the Web user, as it has usually been interpreted - extreme or epiphanic experiences - but can be referred, instead, to all those events that stimulate a high level of attention in the customer, causing him a sense of satisfaction and enjoyment. This seems to rightly involve the shopping experience too. A correct interpretation of the tipology of the experience created for and with the support of the customer becomes fundamental not only to verify at any moment the direction undertaken and the coherence with what has been planned and with the aims of the firm, but also to quantify the significance produced by the considered event compared to the sacrifice. That is the engagement the consumer is required to make use of. It’s evident that market oriented firms, aiming at objectives of excellence, find in customer satisfaction their differentiating plus, compared to their competitors. This happens especially when customer satisfaction can be enhanced through high quality of the goods/services supplied, thus not only as abstract and intangible added value, but as a result of concrete actions. Carrying out a flow experience, however, is also part of the capacity to limit the sacrifice required of or experienced by the customer within low levels, amplifying the effects of satisfaction. In fact sacrifice, meant as the difference between what the customer demands in the specific situation (his wishes) and what he contents himself with, can be removed, or at least balanced, appealing to the product in itself, modifying, therefore, its functions, or acting on its representation (communication, packaging, brand etc). Varying or keeping one of the mentioned aspects, with regard to different sacrifice typologies of the consumer, we can point out four approaches to mass personalization applicable by the firm, thus identifying an effective solution in increasing the value of global experience. This is different from planning the offer referring to a medium customer, previously defined as a conceptual abstraction and, therefore, expressing a solution that can displease almost everybody (consequently amplifying rather than reducing sacrifices). A first kind of sacrifice the consumer undergoes concerns making multidimensional decisions, in order to satisfy needs that are not satisfied by mass offer. Collaborative personalization, in such a case, allows planning solutions directly getting information from the user, who is offered an exploration experience (of the possible alternative solutions). Adaptive customization, instead, is used to eliminate a kind of sacrifice linked to the difficulty of selection in front of business proposals characterized by wide and deep ranges. By promoting customer direct participation in selecting a functionality-to-be-personalized pre existent in the supply, experimentation experience is enhanced at the same time. Cosmetic customization, instead, allows supplying a different standardized product to satisfy different customer requirements, playing on its presentation (commercialisation, label or package). This way, the consumer lives a gratifying experience, because he finds the firm supply (though unchanged in its basic functions) arranged according to his personal cues (for example the web site eshirt.it gives the opportunity to personalize clothes and accessories you want to buy with pictures, photos and printings or to pick up the package and labels to post presents). Finally, the elimination of the unwished intrusion by the firm - with consequent simplification of the interactions - obtained through transparent personalization (that is personalizing the supply in the following interactions, on the basis of the customer spontaneous indications in the first contacts and stored in special databases), allows the purchaser to appreciate the essential nature of the supply without having to concentrate on repetitive and borings details. In such a way, the sacrifice of a continuous repetition is pulled down (escaping experience). All this represents the ground on which the surprise to be stimulated in the customer has to be based. Such a surprise comes from a “romantic” interpretation of the experienced offer, proposing unexpected, surprising uses, thus getting detached from the past. Though simple in its content, surprise makes the experience extraordinary, that is particular, thanks to the unexpected it contains. From an operative point of view, combining the 3 S model (sacrifice, satisfaction, surprise) with the impact the event has on the customer – as to utilitarian and emotional participation, that is as the importance the event has within the individual’s significance system – it is possible to determine the value that has been produced or that can be proposed from the experience (figure 2). Provided that the outcome aimed at by the firm is the transformation of sacrifices into surprises, that is rewards (obtained as the margin between customer perceptions and 6 wishes), it is possible to outline a score system from 1 to 3, where 1 identifies acceptable sacrifice or ordinary surprise and 3 is for any unbearable sacrifice or priceless experience. The aim is to express in quantitative terms the whole value experienced by the user (7). Customer loyalty is evidently aroused when a higher score is obtained (in absolute terms) for surprising events, that is for extraordinary and priceless events, compared to the score for experiences within sacrifice dimension (8). Understanding the potentialities in a surprise-causing consumption situation, together with the attraction power played on the cyber-consumer, therefore, provides elements explaining the complexity of consumption behaviours themselves and of the experiences carried out. Experiences end up representing real options of life, often pre-existent to firm intervention, but endowed with meaning only if properly recognized by the customer thanks to a supply and communication plan capable of making them come out. 3. ON LINE EXPERIENCE SPACE: THE COMMUNITY ROLE The cyberspace represents, without any doubt, a place where the web navigator can go through new extremely involving shopping experiences, in which his whole attention is focused on specific activities or experiences. Virtual space is in itself a stimulating and challenging place, ideal to create situations that can catch the mental energy of the user, who remains the only director of his navigation route. Of course, the probability for the user to experience amazing conditions decreases with increasing electronic surfing. In fact Web browsing will mainly go through favourite links, previously appreciated. The firm aim will be to spot the moment when the Web navigator can reach the "zenith" of his positive experience on the Web. Only through searching this experiential space, there will be the opportunity to get precious information to improve on line services. It is necessary to specify that connection to the net is not sufficient to guarantee the realization of flow experiences; these, in fact, as already pointed out, are more likely to take place when more conditions occur at the same time, both exogenous (connection speed, presence of catching multimedia elements, etc.) and endogenous (customer predisposition and attitude, absence of disturbing factors and time limitations). Analysing the various behaviours of Internet users during their navigation, therefore, becomes particularly important (Prandelli E., Verona G., 2002). From this point of view, two perspectives can be pointed out, the first referring to the case when Web navigation answers to a specific aim (goal-oriented mind set), the second being typical of navigation aimed at searching new experiences (experiential mind set) (figure 3). Such an analysis becomes fundamental if we consider that the firm is now worried about the necessity of monitoring customer needs through all the phases of goods and/or services exchange, and of getting to know, soon and better, possible latent needs or discrepancies in the perceived value. Compared to the past, being present on the market space through interactive relations is no longer sufficient to get deep knowledge of the significant differences between customer groups. A forum, in which consumers interact, exchanging their opinions, perceptions and feelings, is moved into Web micro-systems, reproducing a social dimension where hypermedia communication can avoid its traditional limits (9). The participants’ diversity, characterizing the virtual community, recovers, in part, the emotional content, otherwise absent in similar communicative forms. The use of “emoticons”, namely icons representing facial expressions connected to specific feelings, is only an example of the electronic vocabulary used by on line tribal communities. From this point of view, the privileged place for the users to communicate their own experience, whether positive or negative, will be, without any doubt, the virtual community. The power of the community consists in including the two big macro-categories of Web users, that is active and passive one. The former can be essentially referred to a communication set where privileged interactions between firm and consumers take place (one-to-one). The latter, instead, is similar to mass communication customers, “passively” subject to the different communication actions present in the cyberspace (one-to-many). Communication, occurring within the community, can be defined by the relation many-tomany, as the participants carry out informative exchanges without a unique recognized and legitimate source (10) (figure 4). At the beginning of the Internet phenomenon it was thought that it was communication technology that determined the public mind set, so mass communication users were 7 exclusively associated to traditional market. This position, however, lost sight of the enormous potentialities the market space can offer for the development of effective relational marketing strategies. The navigator’s mind set is not only of an exploratory/hedonistic type, thus characterized by an almost “obsessive” desire to experience new situations. Web users are, in fact, also a mass audience, thus not necessarily obsessed by the need of always being active (Prandelli E., Verona G., 2002). Creating a virtual environment, where to develop effective relational marketing strategies, must allow both interpersonal communication (one-to-one) and mass communication (one-to-many). The Web user wants to gain the option of interactivity, autonomously deciding when to activate it. In this perspective, the community creates the space in which the relation firmcustomer can appeal to the value of loyalty. In fact the deep knowledge given by such virtual space allows the organization to supply personalized and, subsequently, customized services. The invisible participation to the community, hidden in the role of an active member, allows perceiving useful signals to arrange offers modelled on the needs expressed by members, without these being aware of their role of information spreaders. The participants’ indirect involvement in the project phase of on line goods and/or services supply, allows the firm to optimize its own resources, aiming at specific policies of differentiation/personalization. This way, in fact, the firm can “approach” a variegated range of users, though within a limited portion of market, namely the community. The benefits of this activity can reveal themselves to be extremely different from one field to another. For example, for highly informative activities, the firm can succeed in producing considerable low cost advantages for the customers. In other cases, instead (cosmetics, car, etc.), customer benefits meet very high costs for the firm. Firm participation to independent communities as a hidden member answers to purely informative requirements. However when the firm decides to focus on the management of its own virtual community, the value to be communicated has to be different. In this sense the community is depicted as a precious source of value, as interactions between participants inevitably confirm, explicitly or implicitly, either the success or the failure of a brand and/or of a business. The organ of government will have to exorcise the danger of betraying the expectations of its brand community and be careful to “watch” its interactive and developing dynamics in order to prevent the possible reverse of the medal. The greater risk is to see the virtual community being transformed from a supporter of the brand development and management into a ruthless enemy that, if not listened to and fulfilled in its more pressing requests, can cause considerable damages to the business image, as well as considerable losses. In order to avoid the danger of such metamorphosis, the firm will have to appeal to the consumer’s feeling of identification with the brand, supported by an informative exchange giving value to the spontaneity of the communication between members of the community (many-to-many). Community marketing can become, therefore, a winning business model if the firm is willing to invest on the community, activating learning processes based on collaboration with its customers. 4. VIRTUAL COMMUNITY CONTRIBUTION TO THE VALUE CREATION OF THE FIRM The firm and its management staff have to get informed and be aware of situations, behaviours and values so as to be able to stimulate and integrate them through their best proposal of views, services, and goods. Moreover their offer can be strengthened through exchange of the experiences that the individual consumption actor carries out with other consumption subjects, succeeding in combining the need of subjectivity with the one of globality/socialization of the experience. Those needs would otherwise keep their dichotomy, leaving dissatisfaction in the individual. Such dialectics between the two dimensions of a person gives birth to a reciprocal exchange in which the dimensional union creates a cognitive memory effect. This is not simple recollection (as remembering something from the past), but also the capacity to renew itself (viable memory) (Morace F., 2003). The acceptable basis of the business supply is normally found in the price-quality relation, operating a synthesis based on the relation between the creation of the firm value and firm performance itself. In an overall vision, the price-quality relation expresses the 8 degree of the consumer trust about the capacity of the firm to realize a suitable product to satisfy a specific need. Price is the sacrifice the consumer stands by employing his assets to get satisfaction. The consumer, therefore, weighs, also in perceptive terms, the firm activity, connecting his judgement to the expected quality in a positive way and to the sacrifice planned to get the goods in a negative way. The qualitative level the firm manages to reach in the consumer perception is the means, for the government organ, to meet its obligations with the whole “consumption system”. Consumer sacrifice and his longed for satisfaction are variables on which the relation firm -“consumption system” is built. The ways to manage the sacrifice stand in the capacity of the interacting systems and their ability to be open. The dynamics of consumption system are characterized by a mutual change, sharing value and visions. The two systems have common areas of interests that drawing a common field of action drawn with the value system (figure 5). Inside the relation there is construction of value. Its contents and its dynamics are in the nets of communications. Infact, value creation has its roots in the experiential relation in which consumer has a proof of the process, relation and performance benefit (Cantone L., 2002). Sharing the experience through a H2H (Human-to-Human) (11) approach favours the consolidation of links of familiarization about emotional cognition. They improve the satisfaction with an influence on perceived sacrifice. The contribution of the experience to the performance will be in the direction to lessen the effective sacrifice. The consequence is a value adding more proportional than isolated satisfaction or sacrifice. Satisfaction and loyalty processes activate learning and co-development processes – creating the “inter-organizational” set of the system, emerging from the systemic interaction firm/consumption - and allow managing the relation with the creating-value consumption “system” (Barile S. et al, 2001) (figure 6). The firm can affect these processes and, in particular, the loyalty relation, influencing perception and preference dynamics that start the inter-systemic relation. The kind of need to satisfy is the first move to the search and characterizes the interactive availability of the consumption system. The symbolic content of the firm output is the factor that starts the interaction of the firm-viable system with the consumer /consumption system and outlines the degree of the perceived satisfaction. It can be affirmed that the symbolic content of the product affects the degree of opening, together with the relation intensity (criticality and impact power), within the relation with the consumption system. In the exchange relation, therefore, the firm can create suitable situations to communicate the experiences looked for by the customer. The objective is the creation of a value system just by starting the relation (D’Amato A. et al., 2003) - sharing for changing thus creating occasions for group experiences and for long lasting connections within the group, in order to originate opportunities and communication of experienced situations and meanings. The clan comes into being as a moment of the operating integration and of information in the creation of a value system for the customer, from which the firm value derives too. Here is the clan, an organizational or proto-organizational structure (as a viable system) in which “members are bound together over a very long run (Ouchi W. M., 1984). A clan is formed both in front of uncertainty concerning which goods/services to provide for customer satisfaction and in front of the subsequent difficulty in estimating the individual contribution to creating the product (Ouchi W. M., 1980). A clan outlines a proto - organization through which it is possible to establish a mutual relation of reciprocity and exchange and make it work. This allows a continuous renewal of the relation and provides the basis not only for estimation but also for continuous transformation of the mutable. It’s basically what happens in virtual communities where common values and traditions are used to create the necessary cohesion and trust towards the existence of the community. Some of these present virtual clans appear to be viable and autonomous; rather than merely representing a public, they will be an efficient and effective means to organize efforts towards the uncertainty of the knowledge and mutability characterizing the present context of global and individual consumption. Sharing values, beliefs and traditions and having community and solidarity of purposes, allow realizing the transition space in which exchange between community members takes place. This situation creates new spaces of experience by outlining a shared ludic dimension within which new forms of consumption are created. It would be interesting to identify a conceptual basis of analysis allowing going beyond intuition, thus outlining new replicable paths (Lanzone G., 2003). Such basis is given 9 through the sacrifice/satisfaction approach – that allows outlining a path giving way to customer definition of values – and through the virtual community clan, that creates an interactive connection, almost a physiological relation between members of the group. Such relation is founded on a relational exchange between subjectivity of the individuals taking part into it and communication of their experiences (Nonaka I., Toyama R., 2003). Thus a learning process is realized allowing, through everyday interaction within the virtual space, to share individual knowledge. Once being communicated to the group, this leads to innovation as a possible new experience. A further result would be that of a consumption experience lived in a transitive way, allowing preservation of a viable memory. This is meant as a living opportunity to include “the possibility to valorise space and time surrounding us”, as a “replicable event of experiences and stories lived by a people” (Morace F., 2003). Not only does virtual community/ clan memory appear as alive and replicable, but also and above all as renewable. This is possible thanks to its capacity of re-elaboration of new experience in which the emotional past is not only a memory store, but is re-combined through socialization – thus giving inspiration and stimulus towards new horizons for creativity in matters of new forms of consumption and experiences and even identifying the objects through which this can come true. Ensuing from the socialization process inside the community are the processes of internalisation and externalization (knowledge being expressed through conversation and reflection), realizing the necessary synthesis for a new equilibrium in the firm-customer relation. Within this relation the customer is no more a simple endogenous component of value, but an essential component in the enlarged structure of the firm as a viable system, this being plunged in the relation with the consumption system and vice-versa. The firm can become a member of this clan, taking part as an outside subject or as a subject not identified as a firm. Thus it will play an active part, sharing its customers’ consumption experience (table 1). Value mix - as supply of provided value, represented by the whole of the elements given to the customer in terms of concrete product, by the service content and by the capacity to create new situations – is changed and renewed just by creating opportunities and exchange situations. Thus the firm is given the bases on which to re-define its action, its role and its main interlocutor’s (the customer). Actions like the optimisation/reorganization of the chain and the entry into new markets identify strategies for long term keeping of the competitive advantage of the firm and thus of its sustainability itself. 5. CONCLUSIONS Consumption, recognized by Mauss as a global social fact in which the individual experiences his own existential realization, combining everyday his individual and civil dimension, proposes a new interaction field for the firm. The firm doesn’t only have to outline, but it also has to be able to create an emotional interaction with its customer, that is to originate consumption experiences leading to the creation of something new. Business on line appears to be particularly suitable to establish a reciprocal exchange – first between groups of consumers and then between customers and firm – of consumption experiences. This allows the virtual opening apt to establish, between consumers and firm, the necessary dialogue to start an exchange flow. This will allow containing within low levels the sacrifice the customer supports, amplifying the effects of satisfaction, through experiencing particular or extraordinary situations. In order to achieve this, the firm needs not only to carry out a dialogue one to many through Web interaction (e.g. forums), but also to test, monitor and create, through communication and reception of the emotions the consumer/customer feels about its proposals. The consumer/navigator that surfs the Web with an exploratory spirit, led by a ludic and cognitive motivation, participates in the communities, activating a relation many-to-many as he carries out informative exchanges without a unique and identified source of authority. This source will be identified just in the group within which the customer will share his experiences, values and also, in time, traditions. These features belong to organizational systems that are based on the structure of the clan in which the relational component, consolidated in sharing a common belief or intent, prevails. Thus it becomes possible for the groups and the firm to find a common 10 field of action where the customer has the opportunity to create his own satisfaction just as his needs come out, while the firm can re-position itself along the continuous progress that it will be able to outline even together with its target customers. Thus the firm will be able to identify the changes in behaviour as they occur, so as to go on creating value and keeping its own competitive advantage. Selected bibliography ADDIS M., “Nuove tecnologie e consumo di prodotti artistici e culturali: verso l’edutainment”, in Micro & Macro Marketing, n. 1/2002 ALVISI M., Da consumatori a consum-attori, www.mymarketing.net, 2004 BARILE S., BUSACCA B., COSTABILE M., “L’innovazione negli studi sui processi di consumo: vettori evolutivi e percorsi di ricerca”, in Sinergie, n. 55, 2001 BUCCHETTI V., (a cura di), Design della comunicazione ed esperienze di acquisto, Franco Angeli, Milano, 2004 CANTONE L., "Creazione di valore per i clienti e relazioni tra imprese nei mercati business to business: i cambiamenti indotti dalle nuove tecnologie dell'informazione e della comunicazione, in Congresso internazionale “Le tendenze del marketing”, École Supérieure de Commerce de Paris-EAP, 25-26 Gennaio 2002 CARÙ A., COVA B., “Esperienza di consumo e marketing esperienziale: radici diverse e convergenze possibili”, in Micro & Macro Marketing, n. 2/2003 CSIKSZENTMIHALYI M., Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience, Perseus Book, New York, 1997 D’AMATO A., TORTORA D., ZOCCOLI P., “La customer satisfaction e il sistema di consumo: ipotesi per la creazione di un differenziale competitivo”, in Esperienze d’impresa, S/1, Special Series, 2003 DI NALLO E., Quale marketing per la società complessa?, Franco Angeli, Milano, 1998 GOLINELLI G. M., L’approccio sistemico al governo dell’impresa. L’impresa sistema vitale. vol. I, Cedam, Padova, 2000 GRANDI R., Cultura d’impresa e corporate identity: valori, credenza, fiducia, cambiamenti e centralità del punto di vista semiotico, in FERRARO G., (edit. by), L’emporio dei segni, Meltemi Editore, Roma, 1998 LANZONE G., “Complessità del mondo e scenari di previsione”, in Sviluppo & Organizzazione, n. 197, May/June 2003 LASALLE D., BRITTON T. A., Priceless, Etas, Milano, 2003 MATHWICK C., RIGDON E., “Play, Flow, and the Online Search Experience”, in Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 31, September 2004 MORACE F., “Il marketing dell’esperienza, la felicità, i generi e le generazioni”, in Sviluppo & Organizzazione n. 197, May/June 2003 NONAKA I., TOYAMA R. , “L’impresa che crea conoscenza", in Sviluppo & Organizzazione, n. 197, May/June 2003 OUCHI W. M., “Markets, Bureaucracies and Clans”, in Administrative Science Quarterly, 25, March, 1980 OUCHI W. M., “The M-form organization”, in Human Resource Management, Summer 1984, vol. 23, n. 2 PINE J. B.,GILMORE J. H., L’economia delle esperienze. Oltre il sevizio, Etas, Milano, 2000 PORTER M.E., Il vantaggio competitivo, Edizioni Comunità, Milano, 1987. PRANDELLI E., VERONA G., Marketing in rete, McGraw-Hill, Milano, 2002 RIFKIN J., L’era dell’accesso. La rivoluzione della new economy, Arnoldo Mondadori Editore, Milano, 2000 SIANO A., “Comunicazione per la trasparenza e valori guida”, in Sinergie, n. 59/02 SIANO A., Competenze e comunicazione del sistema d’impresa. Il vantaggio competitivo tra ambiguità e trasparenza, Giuffrè Editore, Milano, 2001 SIRI G., La psiche del consumo. Consumatori, desiderio e identità, Franco Angeli, Milano, 2001 VESCOVI T., CHECCHINATO F., “Luoghi d’esperienza e strategie competitive al dettaglio”, Congresso Internazionale “Le tendenze del marketing”, Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, 28-29 November 2003 11 Notes (1) In this case we can distinguish the experience of the individual, based on common sense and generating individual knowledge, from the scientific one, bringing universal knowledge. (2) Thus single subjective experience gains value to the detriment of general models. (3) Here goes the flourishing of marketing studies, pointing out the increasing attention to the customer centrality, first in terms of relations (relational marketing), then of cognitive and emotional involvement (experience marketing). (4) This component evidently acts as a strengthening element, fortifying, just thanks to the experienced satisfaction, the integration with the group that makes it possible. (5) There is a new challenge for the firm: in order to conquer competitive advantages, to be able “to do” is no more as crucial as to be able to make this firm specific ability visible. New must “to make it known”, through explicit communication of one’s own distinctive competences. This is a dichotomy played on ambiguity and transparency, the former to protect distinctive knowledge, the latter as a necessary preliminary condition of explicit communication and a new difficulty for the firm. (6) In his work on the issue of business culture and its realtion to corporate identity, Grandi, following Berstain’s study, mentions three kinds of identity, aiming at outlining the idea of corporate identity. Accordino to it, we can speak of “identity as sameness, which implies the principle of coherence; as individuality, which implies the link with personality; as mark, identifying the owner, which implies identification of the brand”. According to Berstain, therefore, corporate identity outlines planned visual messages, capable of symbolizing the firm, thus allowing the public to recognize and distinguish it. In the author’s opinion, the limit of this position consists in linking the issue of visual identity only to a communicative dimension. Instead, Grandi himself defines the concept in a different way, conveying into the idea of corporate identity all that has to be valorised and communicated about the firm. In doing this, he considers a series of interpretative ties (concerning tangible aspects, such as firm structures and markets, and pre-existent matters leading to the firm history, present – its mission – and future – strategic planning; finally ties coming from the interpretation of the firm positioning and product) emerging just in the attempt of outlining credible identity features. (7) It has to be noticed that in ordinary events the score attributed to surprise - almost non existent or not such as to be perceived by the customer - and to sacrifice – acceptable, as being expected before buying, such as in front of ludic, esthetic, educative experiences - is identical. (8) For example, if the customer has been involved in an ordinary experience and two extraordinary ones (for a total score of 1 + 2*2 = 5), three unacceptable experiences (sacrifices) and an intolerable one (2 * 3 + 3 = 9), the negative experiences, that is what has been experienced along the sacrifice dimension, overcome the positive events (along the surprise dimension) for a score of 9 to 5. That means no value experience has been perceived. (9) Mediated communication, as impersonal communication, is considered little exciting; the highly informative content that characterizes it, in fact, corresponds to a modest social content, because of the lack of not oral codes. (10) Another way to communicate on-line is the many-to-one type in which several Web users address the same interlocutor. An example is that of the virtual auction. (11) Human to Human approach is employed as Human Resource Management approach. In our vision, the relation with the consumer is inside the system of value of the firm and, then, inside of it. 12 Figure 1 - Connecting consumer studies Consumption Experience Instrumental orientation Hedonic orientation Satisfaction pursuit of maximum utility Relation Pleasure Action pursuit of fantasies, feeling, fun Stimulus emotion as characteristics of the product and consumption emotion as a form of perception of the product characteristics Figure 2 - Events-experience matrix = Customer perceptions > Customer expectations Sacrifice = customer wishes > acceptable performance Surprise = Customer perceptions > customer wishes KINDS OF EVENT/ FEELING PERCEIVED Satisfaction surprise ordinary experience priceless extraordinary experience experience Zero or modest impact experience satisfaction acceptable experience sacrifice low unacceptable experience unbearable experience medium high IMPACT 13 Figure 3 - Types of Web customer mind-sets NAVIGATOR’S MIND SET Deliberative Operating Exploratory Goal-oriented mind set Types of BtoC web sites Stand alone Isp Intelligent agent Hedonistic Experiential mind set Vortal Generalistic e-tailer Auction Virtual stores Customerfocused e-tailer Forum Virtual community Blog Rational factors’ influence Emotional factors’ influence Figure 4 - Communication types in Web market Web Market one-to-one many-to-many many-to-many one-to-many (community) ( Figure 5 - Firm – consumption system interactions Consumption system Legend: relation price interaction satisfaction product Sub-systems for value creation Production system firm PPPrrrooocccuuurrreeem m meeennnttt H H m R M m Huuum maaannnR ReeesssooouuurrrccceeeM Maaannnaaagggeeem meeennnttt TTTeeeccchhhnnnooolloloogggyyydddeeevvveeello m loopppm meeennnttt FFFiirirrm i n f r a s t r u c t u r e m i n f r a s t r u c t u r m infrastructuree IIInnnbbbooouuunnnddd LLLooogggiisisstttiiciccsss O O Opppeeerrraaatttiioioonnnsss Outbound Logistics Value for customer M M & Maaarrrkkkeeetttiin innggg& & SSSeeerrrvvviicicceeesss SSSaaalleleesss Consumption system 14 Figure 6 - Value system Source: adapted from PORTER M.E., Il vantaggio competitivo, Edizioni Comunità, Milano, 1987 Table 1 - The centrality of the customer: Views and tools Principles Customer-Focused Proposition Customer-Driven Organization Customer relation means “Traditional” View (Segmentation+ “Value” View Marketing mix) (value mix + value profile) + Value System Formulating a portfolio that satisfies Formulating a value system to satisfy profitably homogeneous groups of profitably customer value profile. customers. (Value Profile of Perceived value) (Segmentation) Placing the portfolio on the market Placing the value proposal on the integrating it with functional market integrating it with components components of customer satisfaction. of released value for customer satisfaction. (Marketing Mix) Value system: Enacting the relational exchange satisfaction-sacrifice through intersystemic interaction. Carrying out action and exchange through consumption micro structures such as virtual communities for on line business Source: adapted from LASALLE D., BRITTON T. A., Priceless, pag. XXVIII 15