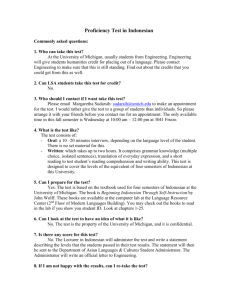

British Intelligence and Propaganda during the `Confrontation`, 1963

advertisement

This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in Intelligence and National Security in 2001, available online: http://www.tandfonline.com/ DOI:10.1080/714002893 British Intelligence and Propaganda during the ‘Confrontation’, 19631966. DAVID EASTER The 1963-1966 ‘Confrontation’, or undeclared war between Britain, Malaysia and Indonesia, provides a good example of a successful counter-insurgency campaign. Indonesia’s attempt to break up the Malaysian federation by sponsoring a guerrilla movement in Borneo was decisively defeated. Explanations for this victory have tended to focus on Britain’s military tactics. A recent study concluded that Britain and Malaysia’s success was mainly due to the mobility provided for British and Commonwealth troops by helicopters, the effects of secret ‘Claret’ cross-border operations and field intelligence.1 However, evidence has also emerged of British propaganda and wider intelligence work during the Confrontation and these were important factors in Britain’s victory. British strategy and policy was heavily influenced by human and signals intelligence. In particular, signals intelligence gave Britain the confidence to launch the Claret crossborder raids into Indonesia, which were so crucial in containing the Indonesian guerrillas. At the same time Britain carried out an aggressive propaganda campaign against 1 Indonesia that might have played a major role in the removal of the Indonesian leader, Achmed Sukarno, and affected Jakarta’s decision to end the Confrontation in 1966. To understand the significance of British intelligence and propaganda it is necessary to briefly explain what the Confrontation was. In 1961 Britain and the Malayan Prime Minister, Tunku Abdul Rahman, decided to create a federation of Malaysia by merging the British colonies in Borneo and the island colony of Singapore with already independent Malaya. London was attracted to this scheme because it saw Malaysia as a way of preserving its major military base in Singapore. The pro-Western Tunku would become the Prime Minister of Malaysia and he was prepared to let Britain carry on using the Singapore base. From January 1962 President Sukarno of Indonesia openly opposed the Malaysia plan. He denounced Malaysia as a neo-colonialist plot to maintain a British presence in the region and claimed that it denied Borneans their legitimate right to self-determination. Under Sukarno’s leadership Indonesia embarked on a policy of ‘Confrontation’, exerting diplomatic, economic, political and military pressure against London and Kuala Lumpur. From April 1963 guerrillas made raids into Borneo from the neighbouring Indonesian territory of Kalimantan. Malaysia was nonetheless set up in September 1963 but Sukarno carried on and even escalated his Confrontation campaign; from August 1964 Indonesian guerrillas made landings in peninsula Malaya. British and Commonwealth troops defended Malaysia against the Indonesian attacks, and although Singapore split from 2 Malaysia in 1965, Confrontation proved a failure. Indonesia was forced to accept the new state. INTELLIGENCE Britain had several sources of intelligence during the Confrontation. On a local, tactical level cross-border reconnaissance by British and Commonwealth troops and co-operation with the indigenous border peoples provided important information on the activities of the Indonesian guerrillas. Other tactical intelligence came from the interrogation of Indonesian prisoners and analysis of captured documents.2 On a broader scale Britain had access to strategic intelligence; intelligence that could be used to shape Britain’s overall policy and military strategy in the Confrontation. This intelligence was gathered through three main sources: air photo-reconnaissance, human agents (Humint) and intercepted Indonesian signals (Sigint). From 1963 until 1966 RAF planes carried out secret overflights of Indonesia, photographing border areas, airfields and guerrilla infiltration bases, and obtaining useful information on Indonesian military deployments3. A variety of sources offer evidence for Humint and Sigint operations. A former British official, who did not wish to be identified, has confirmed that Britain had agents within the Indonesian government and military.4 There are also hints in released British 3 documents that London broke the Indonesian ciphers. For example in 1965 the Foreign Office was concerned over the possible sale of advanced American communications equipment to the Indonesians because of the ‘intercept aspect’. The Foreign Office wished to ensure that ‘the GCHQ interests are fully appreciated’.5 In 1969, after the conflict had ended, the Chiefs of Staff discussed whether Sigint should be included in a prospective official history of the Confrontation.6 More evidence for British Sigint is provided by Spycatcher, the memoirs of former MI5 officer Peter Wright. In his book Wright described ways of intercepting and deciphering encoded messages by placing listening devices in or outside foreign embassies. He recalled that ‘We operated in the same way against the Indonesian Embassy at the time of the Indonesian/Malaysian confrontation, and read the cipher continuously through the conflict.’7 Again a former British government official has confirmed that Britain did break the Indonesian ciphers during the Confrontation and was able to read both diplomatic and military traffic.8 In addition to intercept operations against the Indonesian Embassy in London Britain could target Indonesian communications from listening stations in Hong Kong and at Phoenix Park in Singapore. The collected intelligence on Indonesia was then shared with the Americans, who had their own, high quality sources of information.9 The extent of Britain’s intelligence penetration does appear impressive and certainly the Joint Intelligence Committee (JIC) received ‘ministerial commendation on the quality of its reporting on Malaysia’.10 However, it is hard to establish the exact value of this 4 intelligence to British policymakers during the Confrontation. Released JIC assessments of Indonesian intentions and capabilities conceal the sources of their information, making it difficult to see what material the air reconnaissance, Sigint and Humint was actually providing.11 Nonetheless with the fragmentary evidence available some preliminary conclusions can be drawn. Firstly, the strategic intelligence seems to have confirmed the British in their view that Indonesia was implacably hostile to the creation of Malaysia. For example, in January 1963 the British High Commission in Kuala Lumpur informed London about the latest reports from ‘our friends and their friends’ [often a euphemism for the intelligence services], which indicated ‘increasing determination on the part of Indonesians to unmask Tunku as arch-neo-imperialist and to frustrate Malaysia.’12 In August 1963 a decrypted Indonesian telegram stated unambiguously that ‘The anti Malaysia movement (actions) is aimed at the overthrowing of British power in South East Asia’. 13 When Singapore separated from Malaysia in August 1965 London found that ‘Instructions from Djakarta to Indonesian posts suggest, as expected, intention to treat Singapore secession as result and first fruit of confrontation; further fruits to be gathered include Borneo wind falls and withdrawal of British base’.14 These reports fed a general British belief that it was futile to seriously negotiate with the Indonesians over Confrontation because Sukarno was determined to destroy Malaysia and remove British influence from the region. A Foreign Office paper presented to the Cabinet in January 1964 warned that in talks Indonesia might ask for restrictions on 5 Britain’s use of the Singapore military base or demand a plebiscite in Borneo on whether the territory should remain part of Malaysia. Unless Britain and Malaysia were prepared to make these kinds of dangerous concessions it would be useless for them to contemplate a negotiated solution until ‘Indonesia had first been brought to her knees by a prolonged process of attrition’.15 A joint Foreign Office/Commonwealth Relations Office paper produced for the new Labour government in January 1965 was even more suspicious of Indonesian intentions. It claimed that Indonesian opposition to Malaysia was ‘inevitable’ because Sukarno had ‘a long-cherished ambition to seize Malaya, politically if not territorially’.16 The paper argued that there was not likely to be a sincere Indonesian desire for negotiations in the near future. Britain would have to maintain the defence of Malaysia and ignore any diplomatic approaches from Sukarno. This tough line in the Confrontation was not initially supported by all of Britain’s allies. The United States in particular wanted to establish a modus vivendi with Sukarno because of Indonesia’s strategic importance in the Cold War. Consequently during 1963 the State Department and the White House pressed for talks between Kuala Lumpur and Jakarta, in the hope that Sukarno might drop his opposition to Malaysia if some kind of face saving political formula could be found.17 London regarded all these efforts as tantamount to appeasement and tried to rein in Washington. It was here that Britain again seems to have made use of its strategic intelligence sources. Intelligence on Indonesia was passed on to American policymakers in order to convince them of Indonesia’s deepset hostility towards Malaysia. In September 1963 the Foreign Office suspected that Averell Harriman, the American Assistant Secretary of State for Far Eastern Affairs, did 6 not believe Sukarno was determined to destroy Malaysia through Confrontation.18 In order to convince him, the Foreign Office told the British Ambassador to show Harriman a ‘Top Secret document’ which demonstrated that ‘the Indonesian Government have set their face against coming to a settlement with Malaysia or seeking to maintain tolerable relations with Her Majesty’s Government.’19 In January 1964, after the Americans had surprised London by sending Robert Kennedy, the Attorney General, to South East Asia to arrange negotiations, Britain went a stage further. When Kennedy stopped off in London on his way back to Washington British officials showed him the raw Sigint material.20 These efforts may have had some effect because by the autumn of 1964 American policy towards Indonesia had fallen more in line with the British position. However, this seems to have been due more to Sukarno’s own increasingly aggressive and anti-American behaviour than Britain’s lobbying use of intelligence.21 Britain also used her intelligence sources to gather information on the state of Sukarno’s health. This rather morbid interest was caused by Britain’s strategic predicament – as there appeared no chance of an acceptable political settlement while Sukarno was in power, London hoped that his early death might open up a way to end the Confrontation. This was not merely wishful thinking, for Sukarno was believed to be suffering from a kidney stone. Confirmation of this came in December 1964 when a ‘CX report’, a Secret Intelligence Service (SIS) intelligence report, showed that Sukarno did have a kidney stone. The CX report revealed that Sukarno's Viennese specialist had recommended more 7 X-rays before the stone could be removed in an operation.22 Britain also managed to covertly obtain X-rays of the Indonesian leader.23 Unfortunately for London the medical intelligence proved to be of only limited value. In January 1965 the JIC made a prognosis that without an operation on his kidney Sukarno was unlikely to live more than a year. If he had a successful operation he might last as long as two to three years.24 However, the JIC’s forecast turned out to be overly optimistic, for although he had persistent kidney problems Sukarno lived on until July 1970. Analysis of Sukarno’s health had also indicated that he might have uraemia, a form of blood poisoning caused by chronic kidney failure. The British Chiefs of Staff (COS) were warned in January 1965 that Sukarno’s uraemia ‘could lead to a condition bordering on mania and the consequently far greater possibility of his making rash decisions’, something which dictated a certain degree of caution in Britain’s actions.25 For example the COS advised that if ministers wanted to initiate a war of nerves in the Confrontation it would have to be directed at the Indonesian army rather than Sukarno, because of his ‘known irrationality’. Sukarno’s possible uraemia illustrated a wider problem that hindered the use of Britain’s strategic intelligence sources. Whatever his actual medical condition, the Indonesian dictator was certainly volatile, impulsive and prone to sudden grandiloquent gestures, so even with the benefit of good intelligence it was hard for Britain to predict what Indonesia would do next in the Confrontation. Perhaps because of this on occasions Britain’s intelligence sources failed to correctly anticipate Indonesian military and 8 political moves in the conflict. In August 1964 Jakarta was able to surprise London and Kuala Lumpur, and dramatically escalate the Confrontation, by landing guerrillas for the first time in peninsula Malaya.26 Britain was also taken unawares by Sukarno’s abrupt announcement in January 1965 that Indonesia was going to leave the United Nations.27 As withdrawal from the UN seemed totally counter productive to Indonesian interests British officials speculated that Sukarno might have taken the decision while under the effects of uraemia.28 At other times outbursts by Sukarno may have led Britain’s intelligence sources to give misleading information. In May 1964 a SIS CX report warned that at a meeting with the Chiefs of the Indonesian armed forces on 9 May, Sukarno had said he would order the start of ‘local war’ or ‘limited war’ against ‘Malaysian-Borneo’, including air attacks on oil installations in the neighbouring Sultanate of Brunei, if the results of a forthcoming summit meeting with the Tunku were unsatisfactory.29 This report caused a minor panic in London and led the Commonwealth Relations Office to request an urgent appraisal from the JIC. But despite the subsequent failure of the summit an Indonesian attack failed to materialise nor were there any signs that one was seriously being prepared. Sukarno’s comments were perhaps said in the heat of moment and the idea then dropped. Alternatively the JIC suggested that they could have been a deliberate leak to intensify a war of nerves. Sukarno might have made the threat assuming that it would leak out and thereby influence the British and Malaysians ahead of the summit. 9 Notwithstanding the difficulties caused by Sukarno’s mercurial personality and his medical condition, Britain’s strategic intelligence did provide London with useful insights into Indonesian thinking. In particular it allowed British policymakers to see how Indonesia reacted to British military actions in the Confrontation. After the Indonesian landings in peninsula Malaya in August 1964 Britain despatched considerable troop and aircraft reinforcements to Singapore and provocatively sent the aircraft carrier HMS Victorious through Indonesian claimed waters. Strategic intelligence sources showed that these counter measures had worried Jakarta: Indonesia dispersed shipping and redeployed aircraft during the passage of Victorious and London discovered that Sukarno had nervously asked his attaches in Western capitals to report on British intentions.30 The Chairman of the JIC concluded that Sukarno had been convinced that Britain was determined and able to retaliate if there were further attacks. He commented that ‘We know…that our recent actions impressed them [the Indonesians] far more than any words could have done - or had done, over the whole confrontation period’.31 In the same way intelligence was useful to Britain in the area of cross-border operations. In April 1964 London had authorised British troops to cross the border in hot pursuit of guerrillas and in July this permission was extended to allow offensive patrols by British forces up to 3,000 yards over the border into Kalimantan, the Indonesian part of Borneo.32 But these steps were not taken without much trepidation. The Foreign Office and the COS were worried that if the patrols became public they could be used by Sukarno to rally Indonesian morale.33 To avoid creating propaganda opportunities for Jakarta the cross-border operations had to be deniable, in the sense that Indonesia could 10 not prove that the border had been crossed.34 The British government could then maintain the fiction that its soldiers never knowingly crossed the frontier.35 In November 1964 Admiral Sir Varyl Begg, the British Commander-in-Chief in the Far East, asked for permission to extend the range of the deniable patrols to 5 miles inside Kalimantan but this request was rejected by the COS.36 The Chiefs feared that deeper operations might not be credibly deniable and could encourage Indonesia to escalate the conflict. In January 1965 a build up of Indonesian forces in Kalimantan and Sumatra led Begg to again request an extension of the cross-border patrols and this time he was able to use Sigint to support his case. Decrypted Indonesian military signals showed that the local commanders in Kalimantan always reported any clash, even those in which their troops were defeated, as a great victory.37 As Begg pointed out to the COS on 12 January, it had not been necessary for Britain to ever deny a cross-border operation and this ‘might be due to the fact that local Indonesian commanders were loath to report such occurrences, describing imaginary assaults of their own instead.’38 Therefore, Begg argued, larger British cross-border raids, attacking Indonesian camps, staging areas and supply dumps up to a depth of 10,000 yards, offered no greater risk, as the ‘[Indonesian] High Command might well remain in ignorance of them.’ The COS accepted Begg’s argument and recommended that cross border operations be extended up to 10,000 yards, including attacks on specific targets. On 13 January senior ministers gave permission for these deeper, ‘Claret’ cross-border raids, a clear example of Sigint influencing Britain’s military strategy in the Confrontation.39 This example was 11 especially significant because the Claret operations allowed British and Commonwealth forces to win control of the border region and greatly reduce the level of Indonesian guerrilla attacks.40 In general then the strategic intelligence helped British policymakers to gauge how much military force they could or should apply in the Confrontation. London could try to calibrate the use of force so as to deter or counter act Indonesian aggression while at the same time not being so military aggressive itself so as to provoke Sukarno into escalating the conflict. It also meant that Britain could make the most battle and cost effective use of her sometimes strained military resources, a point that was appreciated by the British military commanders. At the close of the conflict in June 1966 Air Marshall Sir Peter Wykeham, the RAF Commander in the Far East, reportedly claimed that …it had been a war where Intelligence had played the vital role. Had it not been for the quality of our Intelligence the forces needed, the states of readiness required and the deployments for reinforcements would have been far higher than had proved necessary.41 PROPAGANDA This section will concentrate on covert and unattributable propaganda, that is propaganda where the government source of the information is concealed. Both sides in the Confrontation made extensive use of this type of propaganda. Indonesia, for example, operated ‘black’ radio stations to whip up popular support for the guerrillas in Borneo. In March 1963 Radio Kalimantan Utara, ‘the voice of the Freedom Fighters of North Borneo’, began broadcasting.42 Based at Bogor near Jakarta, the station carried speeches 12 and messages allegedly from rebel leaders and it urged support for the guerrillas in the struggle against Malaysia. It also broadcast propaganda to British service men in the region. At one point the Tunku was said to be regular listener to Radio Kalimantan Utara.43 Another Indonesian pirate station, Radio Kemam, operated from Sumatra, using Radio Malaya’s wavelength and carrying anti-Malaysia and anti-Tunku material.44 In addition the Indonesians successfully used propaganda to aggravate racial tensions in Malaysia between Chinese and Malays. After bloody race riots in Singapore in July 1964 that left 22 dead, the Joint Intelligence Committee (Far East) noted that …since April Indonesian intelligence had been conducting a series of psychological warfare operations in Malaya and Singapore by means of pamphlets, “black newspapers”, the spreading of rumour and the writing of slogans on walls.45 Indonesia’s black radio stations also played a part in stirring up racial hatred. On 17 July 1964, four days before the Singapore riots, Radio Kemam claimed that the Chinese in peninsula Malaya had killed a Malay Muslim with ‘a pork butcher’s knife’ and forced Malays to eat pork.46 Britain replied in a similar fashion, employing propaganda to influence three different sets of audiences during the Confrontation.47 Firstly, London used propaganda to win diplomatic support for Malaysia from other countries and especially the newly independent Afro-Asian states. Secondly, propaganda was used internally in Borneo to counter act Indonesian subversion, particularly amongst the Chinese community in Sarawak. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, propaganda was directed at Indonesia itself in order to cause divisions and undermine support for the Confrontation policy. 13 The co-ordination of British propaganda in the Confrontation was initially carried out by the Counter Subversion Committee, an informal Foreign Office body set up in 1962 to help co-ordinate counter subversion activities.48 The actual propaganda work in the field was mainly done by officials from the Foreign Office’s Information Research Department (IRD) which specialised in unattributable propaganda, although some ‘black’ operations were conducted by the SIS and army psychological warfare teams. 49 In April 1963, before the creation of Malaysia, an IRD official was sent to the Borneo colonies to help counter hostile Indonesian propaganda and to advise the colonial governors on the use of unattributable propaganda.50 The IRD started to prepare a series of radio feature programmes for Radio Sarawak to appeal to disaffected Chinese youth in the colony.51 The IRD officer also stimulated a flow of information material to London for use in reducing opposition to Malaysia at the United Nations and amongst Afro-Asian states.52 In September 1963 the Borneo colonies and Singapore reached full independence by joining Malaya to form Malaysia and Kuala Lumpur took on more responsibility for the propaganda work. However, the Malaysians lacked the necessary funds, equipment and staff for these types of operations.53 To help them, in November 1963 the Counter Subversion Committee was given a £50,000 subvention from the Secret Vote for use against Indonesian propaganda and subversion.54 Money from this ‘Special Counter Subversion Fund for Malaysia’ was channelled via the British High Commission in Kuala Lumpur to the Malaysian government. An extra IRD officer was also sent to Kuala Lumpur.55 The Counter Subversion Committee itself was upgraded – in January 1964 it 14 was turned into an interdepartmental official committee reporting to the new official Cabinet Defence and Oversea Policy Committee.56 By this time the British and Malaysians had several outlets for their propaganda against Indonesia. The Foreign Office and Commonwealth Relations Office routinely supplied the BBC with telegrams from British overseas delegations that contained information on the Confrontation.57 The BBC could then use this information in its vernacular radio programmes. The diplomatic telegrams were also passed on by the British High Commission in Canberra to the Australian Radio Authority and sent via IRD channels to Radio Malaysia, for use in overseas broadcasts to Indonesia.58 The Counter Subversion Committee felt that the function of the BBC and Australian Radio transmissions to Indonesia was to provide ‘the steady pressure of true facts, the supply of which to the BBC was an important responsibility of the C.R.O. and the F.O.’59 For ‘more pointed propaganda’ Radio Malaysia could be used and it did seem to be effective in this role, for by November 1963 the Indonesian Government had banned its citizens from listening to it, although this ban was widely flouted.60 The Malaysians were also operating their own ‘black’ radio station against Indonesia, ‘Radio Free Indonesia’, which masqueraded as the work of Indonesian émigrés.61 Aside from radio, other outlets for propaganda were being used. In late 1963, after a United Nations report had concluded that the majority of the Borneans supported the creation of Malaysia, the IRD paid for the printing of the report in the Indonesian language.62 The IRD then helped drop copies along the border in Borneo. In December 15 1963 a British official also reported that the Malaysians were running ‘a covert campaign to spread disaffection amongst the Chinese in Indonesian territory’.63 Indonesian guerrilla infiltration bases were targeted as well. On 2 November 1964 RAF and Malaysian planes dropped leaflets on the Indonesian bases used to support guerrilla landings in peninsula Malaya.64 The Malaysians carried out further leaflet drops in April 1965.65 The propaganda pushed several themes. British officials generally agreed that in propaganda aimed at Indonesia, it was pointless to attack Sukarno personally because of his still immense popularity in the country.66 Instead propaganda should criticise ‘bad advisers’, ’ruling cliques’ and ‘the Djakarta gang’. A particular target was the Indonesian communist party, the PKI. Although the PKI was loathed and feared by the Indonesian army, it was a major force in Indonesian politics and had a strong influence on Sukarno. The communists were also enthusiastic supporters of the Confrontation campaign against Malaysia and in its unattributable propaganda the IRD stressed the PKI’s involvement. An IRD pamphlet sent to the Malaysian Commercial Association in the summer of 1964 warned that the PKI was encouraging Confrontation, and thereby breaking Indonesia’s ties with the West, in order to smooth the way for a communist take over.67 Another theme of British propaganda was the untrustworthiness of Indonesian propaganda. Once British troops started to cross the border into Kalimantan in April 1964 London wanted to make it as difficult as possible for the Indonesians to publicly protest about the incursions. The Foreign Office therefore tried to pre-empt any Indonesian complaints by giving Jakarta a reputation for mendacity, exaggeration and distortion. The 16 IRD prepared ‘unattributable material designed to discredit Indonesian propaganda’.68 Admittedly this was not difficult to do, since the Indonesian news agency Antara almost daily carried entirely fictitious accounts of British aggression and guerrilla victories. As the Confrontation progressed through 1964 and 1965 Britain reorganised its propaganda machinery and devoted extra resources to a more active propaganda campaign against Indonesia. This process started in September 1964 with an IRD proposal to create a special propaganda unit in Singapore.69 The special unit would …engage in covert propaganda operations against Indonesia with the aim partly of stirring up dissension between different factions inside Indonesia and partly of giving the impression that the various dissident groups inside Indonesia are stronger than they in fact are.70 In connection with the last point, it is worth noting that by July 1964 the British and Malaysians were giving covert aid to rebels against the central government in the outer Indonesian islands of Sulawesi, Sumatra and Kalimantan.71 The IRD proposal was strongly supported by the British High Commissioner in Kuala Lumpur and quickly approved by ministers.72 However, there were delays before the special unit could be set up as the IRD had problems in finding politically reliable and secure Indonesian writers to staff the unit. By December 1964 this problem seemed to have been overcome and Sir Burke Trend, the Cabinet Secretary, could report that the project was going forward.73 At the same time the propaganda co-ordinating machinery was restructured in Whitehall. In October 1964 the Foreign Office and the Commonwealth Relations Office created a 17 Joint Malaysia-Indonesia Department (JMID) to deal with external affairs relating to the Confrontation.74 The JMID took over from the Counter Subversion Committee the roles of sanctioning counter subversion projects and authorising spending from the Special Counter Subversion Fund for Malaysia.75 In February 1965 the special fund was increased to £85,000, a sign of the increased effort being given to propaganda. There was also more explicit political direction. In February-March 1965 senior ministers approved paper JA(65) 9 (Final) produced by the Joint Action Committee.76 JA(65) 9 (Final) was intended to be a general statement of Britain’s aims in the Confrontation that could provide guidelines for more detailed tactical planning, especially psychological warfare and propaganda from Singapore.77 The paper defined Britain’s ultimate aim as to have a non-communist Indonesia living in good relations with Malaysia.78 To achieve this goal British ‘covert propaganda and clandestine operations’ should try to Undermine the will of the Indonesian forces to attack Malaysia, by representing that their real enemies are the PKI and China and bring home to them that their incursions have consistently failed and that there is no popular support for them inside Malaysia. In addition, covert propaganda should aid and encourage dissident groups in the outer Indonesian islands in order to weaken the Indonesian military effort against Malaysia. Finally, covert propaganda should Discredit any potential successor to Sukarno (since Sukarno’s own position is invulnerable) whose accession to power might benefit the PKI. Any attempt to build up an anti-PKI candidate would be counterproductive. 18 The emphasis in JA (65) 9 (Final) on covert propaganda against the PKI reflected concerns in London about growing communist influences in Indonesia. Sukarno was cultivating closer links with Red China and allowing the PKI to becoming more and more powerful domestically. The Foreign Office feared that the longer he remained in power the more likely it was that he would be succeeded by a PKI government.79 This would put paid to British hopes of being able to find a settlement to Confrontation when Sukarno died, as a PKI led Indonesia was likely to be just as hostile to Britain and Malaysia. The fall of Indonesia to communism would also be a major geo-political defeat for the West in the Cold War. The last part of the reorganisation of Britain’s propaganda apparatus was the appointment of a Political Warfare Co-ordinator in Singapore. Sir Andrew Gilchrist, the British Ambassador to Indonesia, and Lord Mountbatten, the Chief of Defence Staff, had asked for a senior officer to co-ordinate British propaganda and political and psychological warfare.80 In July 1965 this post was approved and Norman Reddaway, the Regional Information Officer in Beirut, was selected for the position.81 Reddaway did not take up the job until November 1965 and by that time political events in Indonesia had completely transformed the situation. On 1 October 1965 a LieutenantColonel Untung attempted a coup d’etat in Jakarta.82 Troops loyal to Major-General Suharto, the commander of the army’s strategic reserve, swiftly put down the rebels but not before they had killed six leading Indonesian army generals. The coup’s origins were obscure but circumstantial evidence suggested that the PKI and Sukarno might have been 19 involved. Certainly the Indonesian army professed to believe this and it arrested PKI members in Jakarta and banned communist newspapers. Suharto also began to gradually challenge Sukarno for political power. For Britain the tumult in Indonesia presented an excellent opportunity to disrupt the Confrontation campaign and smash the PKI, and it quickly made use of its enhanced propaganda machinery. On the 8 October the Foreign Office gave Singapore guidance on the propaganda to be directed at Indonesia at this crucial time. It advised that Our objectives are to encourage anti-Communist Indonesians to more vigorous action in the hope of crushing Communism in Indonesia altogether, even if only temporarily, and, to this end and for its own sake, to spread alarm and despondency in Indonesia to prevent, or at any rate delay, re-emergence of Nasakom Government [government including the PKI] under Sukarno.83 Suitable propaganda themes to achieve these goals were …PKI brutality in murdering Generals and families, Chinese interference, particularly arms shipments, PKI subverting Indonesia as agents of foreign Communists; fact that Aidit [the PKI’s leader] and other prominent Communists went to ground; the virtual kidnapping of Sukarno by Untung etc’.84 As well as smearing the PKI and communist China with unproven accusations, propaganda should build up the army leaders by portraying them as patriotic Indonesians. In order to put across these themes the IRD was trying to stimulate broadcasts to Indonesia by the BBC, Radio Malaysia, Radio Australia and the Voice of America. 85 The press was also being approached, as the IRD tried to get material into newspapers read in Indonesia such as the Straits Times. The same anti-PKI message was to be spread by more clandestine outlets, such as a ‘“black transmitter”’, presumably the one operated by 20 the Malaysians, and ‘I.R.D.’s regular newsletter’, which seems to have been directed at Indonesian troops.86 On the next day, the 9 October, the JMID reported that it was mounting some ‘short term unattributable ploys designed to keep the Indonesian pot boiling’.87 To continue with the JMID’s glib metaphor, over the next few months the Indonesian ‘pot’ completely boiled over. From the middle of October the Indonesian army launched a savage campaign to destroy the PKI, ignoring protests from Sukarno who wanted to protect the party. The army captured and killed Aidit, it encouraged the mass killings of communists by religious groups in Sumatra and Bali, and in Java Indonesian soldiers rounded up and massacred thousands of PKI cadres. In the chaos older hatreds surfaced as Indonesians attacked ethnic Chinese in the country. When the killings subsided at the end of December the PKI had been physically exterminated as an effective political force and an estimated 500,000 people had been slaughtered.88 Throughout this period London did all it could to encourage the destruction of the PKI and strengthen the Indonesian military leaders. On 25 November a draft JMID brief revealed that Britain had been (a) blackening the PKI’s reputation within Indonesia and outside, by feeding into the ordinary publicity media news from Indonesia that associates the PKI and the Chinese with Untung’s treachery plus corresponding covert activity; (b) trying in our publicity to present the Generals as Indonesian patriots, and in no way Western stooges, but rather good anti-imperialists.89 21 Much of this propaganda work was being done in Singapore. The IRD’s special propaganda unit there prepared the ‘Black Indonesian newsletter’ and provided services for psychological warfare operations.90 It had minimal contacts with journalists and broadcasters, leaving this to Reddaway, who was newly installed as Political Warfare Coordinator. Reddaway received news on the situation in Indonesia from British overseas missions, especially the Embassy in Jakarta, and from ‘intelligence available in Phoenix Park’, which was almost certainly Sigint.91 He would then supply information that suited British purposes to news agencies, newspapers and radio via contacts in Singapore, Kuala Lumpur and Hong Kong. The news would be carried out into in the world’s media and return to Indonesia, allowing Britain to influence Indonesian opinion. Reddaway claimed that information in telegrams from Ambassador Gilchrist in Jakarta was ‘put almost instantly back into Indonesia via the B.B.C.’92 Many of the stories had an anti-PKI slant: Reddaway recalled that a story of ‘P.K.I systematic preparations before the coup – the carving of the town into districts for systematic slaughter…was carried by [news] agencies’. The story seems to have been untrue. While the elimination of the PKI removed some of the most vocal opponents of Malaysia and weakened Sukarno, it did not guarantee that Jakarta would end its Confrontation campaign. British propaganda therefore also focused on other targets, attacking advocates of Confrontation such as the Foreign Minister Raden Subandrio and increasingly even Sukarno himself, and promoting the development of a military regime. Reddaway plugged themes such as …the disadvantages of the Djakarta/Peking axis, the guilt of Subandrio & co., the incompatibility of reconstruction and confrontasi [Confrontation] 22 and the advantages for Indonesia of switching to good neighbour policies.93 Subandrio was linked to the communists by a story of a messenger plying between him and Aidit, which was carried by newspapers, agencies and radio.94 Details of money accumulated abroad by Subandrio and Sukarno came out in Hong Kong and were widely publicised. During the spring of 1966 the Indonesian army began to move against Sukarno and Subandrio and in March it effectively carried out a coup d’etat. Sukarno was forced to grant Suharto sweeping political powers, Subandrio was arrested and the PKI was formally dissolved. As the new military government consolidated its position Britain scaled back its propaganda activities, in case they might prove counter productive in the new political climate.95 Instead London would rely on diplomacy, mainly conducted by the Malaysians, to negotiate a settlement with the more amenable Suharto. A settlement was quickly reached. At the end of May Indonesia and Malaysia signed an agreement to end the Confrontation and despite some last ditch delaying tactics by Sukarno, the agreement was ratified in August. Britain had got the result it wanted – a non-communist Indonesia that renounced Confrontation and was ready to live peacefully with Malaysia. But to what extent was this due to British propaganda? This question admits of no easy answer but two points do seem to stand out. Firstly, credit (or blame) for events in Indonesia could not be claimed by Britain alone, for she was not the only outside party trying to influence Indonesian 23 opinion. As mentioned above, Malaysia was also carrying out propaganda operations and they did appear to have an impact. In November 1965 an Indonesian military leader told the Malaysians that even Sukarno listened every day to Radio Malaysia’s overseas broadcasts.96 There are also signs that the Americans may have been using propaganda against the PKI after Untung’s abortive coup.97 The second point is that an accurate assessment of the effectiveness of British propaganda depends partly on the intentions of the Indonesian army leadership. After the coup attempt Suharto and the other generals may not have needed any encouragement to wipe out the PKI, remove Sukarno and Subandrio and end the Confrontation. British propaganda might have been pushing at an open door, urging the army to do things that it was going to do anyway. Too little is known of Suharto’s initial intentions to be able to come to a definite conclusion on this, but it is notable that British policymakers were cautious about how much influence their propaganda had on the generals. In November 1965 the JMID made the modest assessment that the propaganda ‘may have contributed marginally towards keeping the Generals going against the PKI and causing friction with China’.98 Certainly it would be wrong to see the army as merely passive recipients of British propaganda. Indeed they quickly set in motion their own propaganda campaign against the PKI. From 8 October 1965 army sponsored newspapers in Indonesia alleged that the six generals killed in the coup attempt had been tortured and their sexual organs mutilated by members of the PKI’s women’s organisation, Gerwani. These claims were false, as 24 Suharto well knew, for he had attended the autopsy of the dead generals on 4 October. 99 But they served to inflame feelings against the PKI. Furthermore the army leaders actively sought Malaysian help in putting across their propaganda message. On 2-3 November 1965 Indonesian Brigadier-General Sukendro had secret talks in Bangkok with Dato Ghazali Shafie, the Permanent Secretary at the Malaysian Ministry of External Affairs.100 Sukendro explained that the army needed six months to consolidate its position. In this period it would try to widen the basis of its support in Indonesia ‘by re-conditioning the people’s mind to win them to its side’. Malaysian help would be needed to do this; Sukendro said Radio Malaysia should emphasise PKI atrocities and the party’s role in the coup. The station should not give the army ‘too much credit’ or attack Sukarno directly. Sukendro even gave the Malaysians tape recorded statements by Untung in connection with the coup, which could be used as material for broadcasts. He also claimed that the army was trying to discredit the Confrontation policy by linking it with the PKI. A document had been ‘exposed’ showing a plan of the PKI to put pressure on Sukarno to fight Malaysia. More such exposures were planned. Finally, Sukendro said that …means and ways must be obtained to remove SUBANDRIO. Towards this end, KEN requested for assistance in the character and political assassination of SUBANDRIO. He would send us materials of background information which could be used by us in whatever way suitable. We have then the unusual situation of an army conspiring with the supposed enemy to remove its own foreign minister. 25 In light of the above it seems likely that the British propaganda had a greater effect on the Indonesian public rather than the already sympathetic army leaders. Through its manipulation of the international media and its covert propaganda Britain ensured that news coming into Indonesia supported the stories being spread by the Indonesian army. It helped incite people against the PKI, damaged Subandrio and Sukarno’s image in the country and undermined popular support for the Confrontation campaign. Nonetheless it is still hard to measure how important this propaganda was. Potentially it could have been a key factor in removing the PKI and Sukarno and clearing the way for the army to end Confrontation. If so, it would have been a major achievement for British propagandists, comparable to coups in the past such as influencing American opinion in the First World War with the Zimmerman Telegram. By the end of Confrontation British officials were more convinced that their propaganda had been effective. In the summer of 1966 Alec Adams, the Political Advisor to the Commander in Chief in Singapore, summed up Reddaway’s activities and wrote that their ‘impact has been considerable.’101 Yet Adams provided no evidence to substantiate this claim and at present we lack such basic information as polling data on Indonesian public attitudes towards the PKI, Sukarno and the Confrontation or listener and readership figures for British propaganda outlets in Indonesia. This sort of information may not exist anyway but without it it is impossible to establish with certainty whether British propaganda did cause the downfall of Sukarno and end the Confrontation. 26 Intelligence and propaganda were not in themselves war winning weapons. Ultimately Britain’s victory in the Confrontation was due to the ability of Commonwealth soldiers fighting in Borneo to contain and drive back the Indonesian guerrillas, and the political instability in Indonesia which brought down Sukarno. But good intelligence enabled Britain to deploy its limited military resources for the greatest effect. And when a political opening appeared in Indonesia in October 1965, Britain used propaganda against the supporters of Confrontation, although this was not without a terrible human cost. NOTES 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Peter Dennis and Jeffrey Grey, Emergency and Confrontation (Sydney: Allen and Unwin, 1996) p.246-253. Dennis and Grey do mention Britain’s use of Sigint but they do not assess how important it was in defeating Confrontation. Ibid Public Records Office (PRO) DEFE 13/385, Minute Kyle to Thorneycroft, 19 Mar. 1964. PRO DEFE 13/498 Minute M015/2/1 Healey to Stewart, 3 Jan. 1966. This former Commonwealth Relations Office official will henceforth be cited as ‘Official A’. PRO DEFE 25/166, Minute Wright to Acting Chief of Defence Staff, 26 July 1965. PRO AIR 8/2441 COS(69) 7th Meeting, (4), 11 Feb.1969. Peter Wright, Spycatcher (New York: Viking Penguin 1987) p. 113. This former Foreign Office official did not wish to be identified. Henceforth cited as ‘Official B’. Letter from Official A. For evidence of CIA intelligence being shared with the British see PRO DEFE 4/174, COS(65) 57th Meeting, (5), 22 Sept. 1964 and Declassified Documents Reference System (DDRS) 1975 (53C), CIA Tel TDCS 314/02920-64, Jakarta to Washington, 11 Sept. 1964. PRO CAB 159/41, JIC(64) 41st Meeting (9) 13 Aug. 1964. PRO PREM 13/2718, JIC/796/65 ‘Special Assessment - Indonesia’, 4 Oct. 1965. PRO CAB 158/46, JIC(62) 58 (Final) ‘Indonesian Aims and Intentions’, 28 Jan.1963. PRO DO 169/237, Tel 105 Kuala Lumpur to CRO, 24 Jan. 1963. PRO CAB 21/5520, ‘Foreign Office telegram 897/8 from Djakarta refer’, not dated. The word in brackets appears to be an alternative phrasing suggested by the translator. PRO DEFE 25/209, Minute Burlace to APS/Secretary of State, 9 Sept 1965. PRO CAB 129/116, CP(64)5, 6 Jan. 1964. 27 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 PRO CAB 148/19, OPD (65) 25, 26 Jan. 1965. PRO PREM 11/4349, Tel. 7462 FO to Washington, 4 Aug. 1963. PRO DO 169/278, Tel. 1676 Dean to FO, 6 Oct. 1963. Interestingly the CIA, which had access to British intelligence and its own sources, supported British policy and agreed with British assessments of Indonesian motives. See John Subritzky, Confronting Sukarno (Basingstoke: Macmillan, 2000), p. 66-67. However, it seems that the State Dept and the White House ignored the CIA’s views. PRO DO 169/241, Warner to Trench, 24 Sept. 1963. PRO PREM 11/4870, Tel. 9489 FO to Washington, 24 Sept. 1963. Interview and letter from Official A. Corroborating evidence is provided by PRO PREM 11/4906, ‘Report of a conversation between the Foreign Secretary and Mr Robert Kennedy, the United States Attorney General on January 24, 1964’, 27 Jan. 1964. This records that the British ‘showed Mr Kennedy certain evidence which, coupled with President Sukarno’s speech caused us to doubt Indonesian good faith.’ J. Subritzky, op cit, p 121-124. PRO DEFE 25/164, Memo. by D.1.34C, 17 Dec. 1964. This information was provided by a former Foreign Office official who did not want to be identified. Henceforth cited as Official C. PRO DEFE 31/54, Minute DCDS(I) to Chief of Defence Staff, 27 Jan. 1965. The CIA made a similar prognosis in January 1965. According to a CIA memorandum ‘Sukarno’s Viennese doctors believe that unless he undergoes surgery for removal of a kidney stone in the near future he will die within a year or two – possibly sooner and suddenly.’ DDRS, 1981, (274C), Office of National Estimates Special Memorandum 4-65, 26 Jan. 1965. PRO DEFE 4/179, COS(65) 3rd Meeting (1A), 12 Jan.1965. PRO PREM 11/4909, Tel. 1917 CRO to Head, 17 Aug. 1964. PRO FO 371/181560, Tel. 11 Gilchrist to FO, 2 Jan. 1965; Tel. 17 Gilchrist to FO, 3 Jan. 1965. PRO DEFE 4/179, COS(65)1st Meeting (1A), 5 Jan. 1965. It seems to have been the drugs used to treat the uraemia rather than the illness itself that would cause the manic state. PRO DEFE 25/157, Minute Golds to Wright, 29 May 1964. PRO CAB 158/53, JIC (64) 54 ‘Indonesian air attacks against oil installations in Brunei’, 15 June 1964. PRO DEFE 4/174, COS(65) 57th Meeting (5A), 22 Sept. 1964. PRO DEFE 4/175, COS(65) 58th Meeting (4A), 29 Sept. 1964. PRO DEFE 25/161, Minute COS 3052/13/10/64 Annex Lapsley to COS, 12 Oct. 1964. PRO DEFE 4/169, COS(64) 33rd Meeting (7), 5 May 1964. PRO DEFE 13/385, Tel. COSSEA 143 MOD to Begg, 1 July 1964. PRO DEFE 4/167, COS(64) 27th Meeting (4), 7 April 1964. PRO FO 371/179120, Brief by Peck, 7 April 1964. PRO DEFE 13/385, Tel. COSSEA 143 MOD to Begg, 1 July 1964. PRO PREM 11/4908, Tel. 5560 FO to Washington, 24 April 1964. PRO DEFE 4/177, COS(64) 70th Meeting (2A), 26 Nov. 1964. Letters from Officials A and B. PRO DEFE 4/179, COS(65) 3rd Meeting (1B), 12 Jan. 1965. It is not clear why the 28 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 Indonesian commanders acted in this way. Defence Secretary Denis Healey suggested to a Labour MP in 1965 that the Indonesians did not publicise Britain’s cross border operations ‘probably because the army did not wish to accept the loss of prestige that would accompany such an admission’. PRO DEFE 25/170, MO/25/3 ‘Note of a discussion between the Secretary of State for Defence…and Mr Tam Dalyell MP on Wednesday, 13 October 1965.’, 14 Oct. 1965. However, the Indonesian army was also deliberately obstructing Indonesian operations that might provoke Britain and escalate the conflict. See Harold Crouch, The Army and Politics in Indonesia (Ithaca: Cornell University, 1978), p. 69-75. Furthermore in secret contacts with the British and Malaysians in the spring of 1965, army leaders stressed that they did not want to escalate the fighting. PRO FO 371/181498, Tel. 713, CRO to Kuala Lumpur, 4 March 1965. PRO FO 371/181499, Tel. 700 Head to CRO, 20 April 1965.Conceivably then the Indonesian army did not inform Sukarno about the British raids in case he reacted violently and triggered off a wider war. PRO CAB 148/19, OPD(65) 8, 12 Jan. 1965. PRO CAB 148/18, OPD(65) 1st Meeting, 13 Jan. 1965. PRO FO 371/181525, Tel. 142 CRO to Kuala Lumpur, 14 Jan.1965. PRO DEFE 4/198, COS(66) 18th Meeting (2), Minute COS 1394/30/3/66 Lapsley to COS, 31 March 1966. PRO DEFE 13/476, Minute Strong to Healey, 22 June 1966. PRO DEFE 4/179, COS(65) 3rd Meeting (1B), 12 Jan. 1965. PRO CAB 21/5520, ‘Draft White Paper – Indonesia and Malaysia’, 28 June 1963. PRO FO 371/169737, Memo by Cable, 8 Mar. 1963, Tel. 218 Singapore to FO, 29 April 1963. PRO FO 371/169693 ‘Note of a Conversation between Mr Lee Kuan Yew and Mr Moore held on 15th October, 1963.’ Not dated. PRO DEFE 7/2388 ‘Draft White Paper – Indonesian and the British Borneo Territories’, not dated. PRO DEFE 5/154, COS (64) 273, 8 Oct. 1964. D. Hyde, Confrontation in the East (London: The Bodley Head, 1965), p. 100. PRO FO 953/2176, ‘Counter Subversion Committee Record of a Meeting held on May 12, 1964 in the Commonwealth Relations Office.’, 14 May 1964. PRO DEFE 28/145, Minute COS 1350/12/2/64 Watkins to COS, 12 Feb. 1964; ‘Review of activities of Counter Subversion Committee, 1961-64’, 8 Jan. 1965. Paul Lashmar and James Oliver, Britain’s Secret Propaganda War (Stroud: Sutton Publishing, 1998) p. 1, 5. PRO DEFE 11/236, Minute Wild to COS, 19 April 1963. PRO CAB 21/4851, Minute Huijsman to de Zulueta, 11 March 1963. PRO DEFE 28/153, ‘Report on Mr P. H. Roberts’ Tour of Duty in the Borneo Territories’, not dated. PRO DEFE 28/144, Draft letter Chairman of the Counter Subversion Committee to Trend, not dated. Ibid., Minute Wild to Secretary Counter Subversion Committee, 27 Sept. 1963. PRO DEFE 28/145, Minute COS 1350/12/2/64 Watkins to COS, 12 Feb. 1964. PRO CAB 134/3326, SV(66) 19, 22 Aug. 1966. PRO FO 953/2176, ‘Counter Subversion Committee Record of a Meeting held on May 12, 1964, in the Commonwealth Relations Office, 14 May 1964. 29 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 PRO CAB 21/5379, Minute Caccia to Trend, 10 Oct. 1963. SV(64) 1, 1 Jan. 1964. PRO FO 953/2129, Letter D1041/21/63 Joseph to Secretariat Kuching, 2 Mar. 1963. PRO FO 953/2128, Letter P5453/4 Stevenson to Micklethwait, 20 Mar. 1963. PRO FO 953/2176, ‘Counter Subversion Committee Record of a Meeting held on May 12, 1964 in the Commonwealth Relations Office.’ 14 May 1964. PRO DO 169/518, Pilcher to Glass, 5 April 1964. PRO FO 953/2132, Letter SPE30/35/1 Budd to Gauntlett, 4 Jan. 1964. PRO FO 953/2176, ‘Counter Subversion Committee Record of Meeting held on February 11, 1964, in the Commonwealth Relations Office.’ 14 Feb. 1964. Ibid. PRO FO 953/2132, Letter 071/63 Gauntlett to Rivet-Carnac, 25 Nov. 1963. PRO DEFE 28/144, Minute Drew to PS/Minister, 19 Dec. 1963. PRO FO 953/2140, Tel. 2380 Kuala Lumpur to CRO, 25 Oct. 1963. PRO FO 953/2176, ‘Counter Subversion Committee Record of Meeting held on February 11, 1964, in the Commonwealth Relations Office.’,14 Feb. 1964. PRO DEFE 28/144, Letter SPE38/30/1 Bottomley to Costley-White, 21 Dec. 1963. Ibid., Minute Drew to PS/Minister, 19 Dec. 1963. PRO FO 371/181556, Tel. 208 Adams to FO, 30 March 1965. Ibid., Tel. SEACOS 80 CINCFE to Chief of Defence Staff, 11 April 1965. Tel SEACOS 82 CINCFE to Chief of Defence Staff, 12 April 1965. PRO FO 953/2132, Letter 071/63 Gaunlett to Rivet-Carnac, 25 Nov. 1963; Letter SPE30/35/1 Budd to Gaunlett, 4 Jan. 1964. PRO DEFE 28/144, ‘Malaysian Seminar on Counter Subversion’, 22 Oct. 1963. PRO DO 169/516, Letter 2FE/04/51/1 Jenkins to King, 8 Sept. 1964; B712 (R) ‘Communists Smoothing Path to power in Indonesia’, June 1964. PRO DO 169/518, Letter 2FE/50/30/1 Golds to Bottomley, 23 April 1964. PRO CAB 21/5584, Minute Nicholls to Trend, 28 Sept. 1964 PRO DEFE 25/218, Minute Drew to Wyldbore-Smith, 11 Sept. 1964. David Easter ‘British and Malaysian Covert Support for Rebel Movements in Indonesian during the ‘Confrontation’, 1963-66,’ in Intelligence and National Security Vol 14, 4/4 (1999) p. 195-208. PRO CAB 21/5584, Minute Nicholls to Trend, 28 Sept. 1964. Ibid., Minute Nicholls to Gordon, 29 Oct. 1964, Minute Trend to Nicholls, 3 Dec. 1964. PRO FO 371/176501 Golds to Bottomley, 21 Oct. 1964. PRO CAB 134/3326, SV(66) 19, 22 Aug 1966. PRO PREM 13/430, Minute Trend to Wilson on ‘Malaysia’, not dated; Minute PM/65/32, Stewart to Wilson, 26 Feb. 1965; Minute Healey to Wilson, 1 March 1965. PRO FO 371/181503, Golds to King, 1 April 1965. PRO DEFE 5/162, COS (65) 162 Appendix 1, 20 Sept. 1965. PRO CAB 148/19, OPD(65) 25, 26 Jan. 1965. PRO FO 371/181530, Tel. 2645 CRO to Kuala Lumpur, 19 Oct. 1965. PRO FO 371/187587, Letter 90440/2/66G Adams to Murray, 19 May 1966. PRO FO 371/187587, Minute Stanley to Edmonds, 17 June 1966. H. Crouch, op cit, p 97-134. PRO DEFE 25/170, Tel. 1863 FO to Singapore, 8 Oct. 1965. PRO FO 371/181455, Tel. 2679 CRO to Canberra, 13 Oct. 1965. 30 85 Ibid., PRO DEFE 25/170, Tel. 1863 FO to Singapore, 8 Oct. 1965. Ibid. A breakdown of spending by the Special Counter Subversion Fund for Malaysia mentions a ‘Newsletter for Indonesian troops’. It also reveals spending on ‘Rupiah notes as “bait” in magazine aimed at Indonesian troops’ and ‘Polythene sealing machine for floating leaflets down Borneo rivers.’ See PRO CAB 134/3326, SV(66)1, 10 Jan. 1966; SV(66) 24, 30 Nov. 1966 87 PRO FO 371/181530, Tel. 1460 Stanley to Reddaway, 9 Oct. 1965. 88 H. Crouch, op cit, p 155. 89 PRO FO 371/181457, Minute Stanley to Peck, 25 Nov. 1965. 90 PRO FO 371/187587, Letter 90440/10/66G Adams to de la Mare, attached diagram 2 June 1966. PRO FO 371/186956, ‘Hong Kong Heads of Mission Conference Information Policy towards South East Asia and the Far East.’ Not dated. 91 PRO FO 371/187587, Letter 90440/2/66G Adams to Murray, 19 May 1966. P. Lashmar and J. Oliver, op cit, p 6-9. 92 Gilchrist Papers GILC 13/K(iii), Letter Reddaway to Gilchrist, 18 July 1966, Churchill Archives Centre, Cambridge University. 93 PRO FO 371/187587, Letter 90440/10/66G Adams to de la Mare, 2 June 1966. 94 Gilchrist Papers GILC 13/K(iii), Letter Reddaway to Gilchrist, 18 July 1966, Churchill Archives Centre, Cambridge University. 95 PRO CAB 134/3326, SV(66) 2nd Meeting (1), 18 May 1966. PRO FO 371/187587, Minute Stanley to Edmonds, 17 June 1966. 96 PRO FO 371/181457, ‘Record of Meeting between Dato M. Ghazali and BrigGeneral Sukendro on 2nd and 3rd November 1965 at Bangkok’, 10 Nov. 1965 97 H.W. Brands ‘The Limits of Manipulation: How the United States Didn’t Topple Sukarno’, in The Journal of American History Vol 76, 3/4 (1989) p. 802. Brands quotes the US ambassador to Indonesia as recommending on 5 October 1965 covert efforts ‘to spread the story of the PKI’s guilt, treachery and brutality.’ 98 PRO FO 371/181457, Minute Stanley to Peck, 25 Nov. 1965. 99 H. Crouch, op cit, p 140. Geoff Simons, Indonesia: The Long Oppression (Basingstoke: Macmillan, 2000), p 173-4. 100 PRO FO 371/181457, ‘Record of Meeting between Dato M. Ghazali and BrigGeneral Sukendro on 2nd and 3rd November 1965 at Bangkok’, 10 Nov. 1965. 101 PRO FO 371/187587 Letter 90440/2/66G Adams to de la Mare, 19 May 1966. 86 31