Good practice: a statewide snapshot 2014

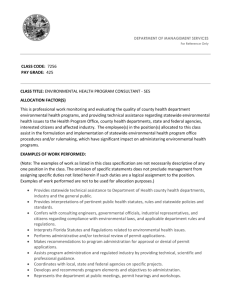

advertisement