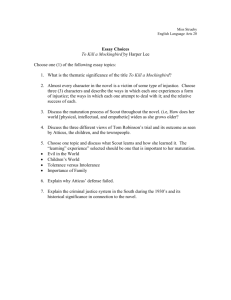

Year 10 mockingbird essays how to.doc

advertisement

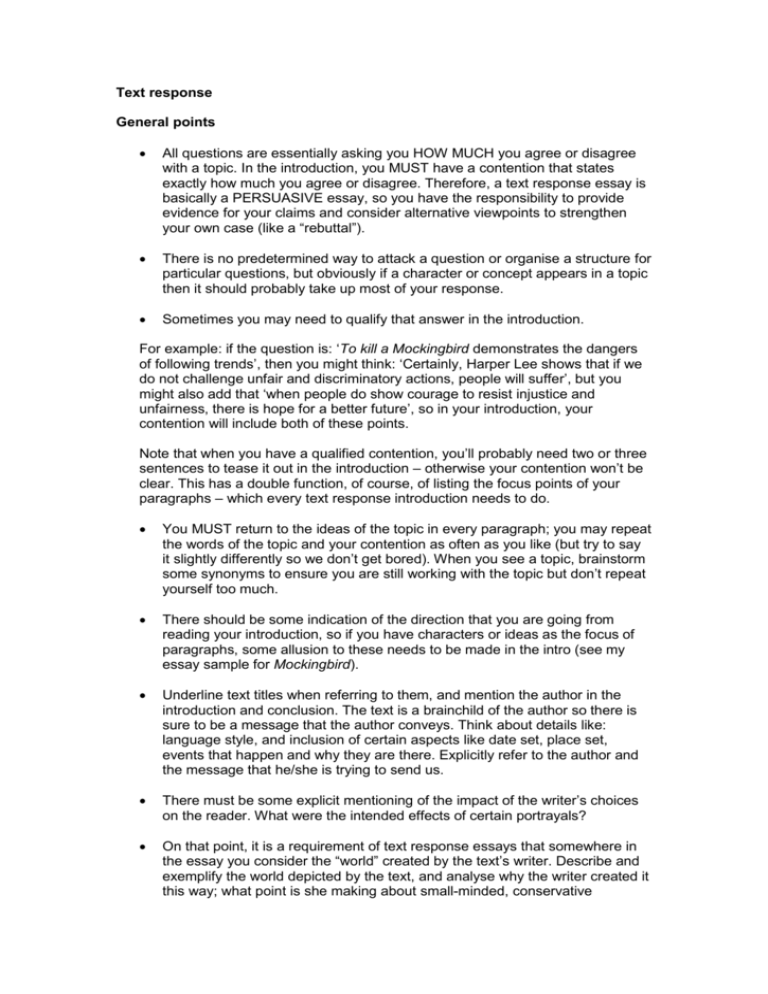

Text response General points All questions are essentially asking you HOW MUCH you agree or disagree with a topic. In the introduction, you MUST have a contention that states exactly how much you agree or disagree. Therefore, a text response essay is basically a PERSUASIVE essay, so you have the responsibility to provide evidence for your claims and consider alternative viewpoints to strengthen your own case (like a “rebuttal”). There is no predetermined way to attack a question or organise a structure for particular questions, but obviously if a character or concept appears in a topic then it should probably take up most of your response. Sometimes you may need to qualify that answer in the introduction. For example: if the question is: ‘To kill a Mockingbird demonstrates the dangers of following trends’, then you might think: ‘Certainly, Harper Lee shows that if we do not challenge unfair and discriminatory actions, people will suffer’, but you might also add that ‘when people do show courage to resist injustice and unfairness, there is hope for a better future’, so in your introduction, your contention will include both of these points. Note that when you have a qualified contention, you’ll probably need two or three sentences to tease it out in the introduction – otherwise your contention won’t be clear. This has a double function, of course, of listing the focus points of your paragraphs – which every text response introduction needs to do. You MUST return to the ideas of the topic in every paragraph; you may repeat the words of the topic and your contention as often as you like (but try to say it slightly differently so we don’t get bored). When you see a topic, brainstorm some synonyms to ensure you are still working with the topic but don’t repeat yourself too much. There should be some indication of the direction that you are going from reading your introduction, so if you have characters or ideas as the focus of paragraphs, some allusion to these needs to be made in the intro (see my essay sample for Mockingbird). Underline text titles when referring to them, and mention the author in the introduction and conclusion. The text is a brainchild of the author so there is sure to be a message that the author conveys. Think about details like: language style, and inclusion of certain aspects like date set, place set, events that happen and why they are there. Explicitly refer to the author and the message that he/she is trying to send us. There must be some explicit mentioning of the impact of the writer’s choices on the reader. What were the intended effects of certain portrayals? On that point, it is a requirement of text response essays that somewhere in the essay you consider the “world” created by the text’s writer. Describe and exemplify the world depicted by the text, and analyse why the writer created it this way; what point is she making about small-minded, conservative Southern American towns in the 1930s through her depiction of settings, characters and events? In all essays, in all subjects, leave a full line of space between paragraphs. Synthesise! The basis of each paragraph should be linked to the given topic. Use examples from different parts of the text to prove that that idea or character is typically like that as presented in the text. Don’t attack a question by giving a chronological list of events; draw examples together from all over the text. The organising principle of your paragraphs is ideas/themes or character types, not stories, scenes or parts of texts. In essence, no storytelling of the text. Avoid appraising the text; it’s not a book/film review. You are not being asked to say how well the writer or director managed to create characters or produce a text, so none of this: ‘an excellent film’, ‘a wonderful book’ etc. Every sentence must be linked to the question posed in the topic; don’t ramble on about your favourite character or use your favourite quote unless it is relevant to the topic. Don’t use “I”, as in “I believe” or “I think”; simply make statements. You are writing so there’s no need to use “I”. We know it’s you!! Never repeat a quote or an example in different paragraphs. Use linking words to connect consecutive paragraphs and in between points or examples in the same paragraph: ‘Similarly, BB Underwood defends Atticus’ bravery by publishing a ‘scathing’ Editorial decrying the result of the trial’; On the other hand; In the same way; It is this kind of behaviour… and so on. Use detached, unemotional, formal language without the use of slang (gonna, a lot, you know) or contractions (don’t, can’t – unless it’s in a quote). In general, do not use boring general words such as: bad, good, a lot, nice, main, thing (you KNOW I hate that word!) and no abbreviations, including: e.g., thru (!!), i.e. and so on. Don’t moralise; in other words: don’t say what characters should or shouldn’t have done… you are not a guru or spiritual counsellor. Treat characters with empathy and understanding. Try and look at any positive aspects of their personality too. Make sure you show that you know the text by being very specific about characters and events in your discussion of characters’ actions. Therefore, never make general statements without providing a specific example to prove it. Also, use precise terminology. Instead of saying: ‘Atticus is good’, say: ‘Atticus Finch remains a constant role-model for all the townsfolk’ (and then prove it through providing a specific example: ‘he rids the town of the rabid dog and ‘was born to do [their] unpleasant jobs for’ them, such as defending a black man in a racist society’). Build up a word bank to describe characters in texts, and find some to describe their actions during specific events. Do this BEFORE the assessment task to ensure you have interesting vocabulary ready. Build quotes into your own sentences; see my sample essay for examples. Quotes should be absolutely correct, short and built into the grammar of your own sentences. Remember the best part of the quote and paraphrase the rest if necessary: “Scout recognises the necessity of defending those who are helpless; she does not understand how people can espouse democracy but then ‘be ugly about folks right at home.” Obviously, metalanguage connected to novels is desirable: “The analogy of the mockingbird motif enables the children to recognise the unfairness of treating the innocent cruelly.” You never need page/scene numbers in essays. You can use quotes ANYWHERE in an essay, including the introduction and conclusion. They must be relevant to a character (that is: an accurate portrayal of a character), and they should not be over-used because they can clog up your fluency and clarity of expression. You may need to use a quote in which the actual verb tense or type will not fit into your sentence. In these cases, use square brackets to show you are changing an original quote. For example: Mr Ewell maintains that he saw Tom Robinson ‘ruttin’ on [his] Mayella’. The original quote is “my” Mayella, but since text responses are written in the third person, “my" doesn’t fit here. Change pronouns and tenses to ensure the grammar of your piece is consistent and logical. Learn at least ten quotes off by heart from the texts you intend to do. More importantly, though, remember events that prove points or exemplify themes. If a quote cannot fit into the grammar of your sentence, for example, if it is a full sentence itself, introduce it at the end of the sentence with a colon (:). For example: “Tom’s paradox is that: ‘they only thing [he’s] got is a black man’s word against the Ewells’.” This quote is clearly difficult to place into the grammar of my own sentence, so I have included the whole quote and introduced it with a colon instead. Use the present tense when talking about events in texts: “Jen comprehends the severity of the conviction” not “Jem comprehended…” Avoid absolute statements: ‘Atticus is always level-headed’ or ‘Mrs Dubose has no redeeming features - (these statements are untrue, and we know it, so don’t say it; instead say: ‘Most of the time, Atticus is level-headed and rational’ (then, prove it through using one or two examples). Structures: Intro: Something philosophical: a social observation, purpose of the text or ideal. Text title, underlined; author’s full name Qualified contention/in order, a list of the essay’s paragraphs Comprehension of genre and social context in relation to the given topic You may throw a couple of short, generally applicable quotes here. Paragraphs: “change” essays need to show: what people were like at the start; what caused them to change (catalysts), then the result. Theme essays need to consider “types of” a trait/behaviour and possibly results, or even a rebuttal paragraph that considers exceptions. For example: “courage” = physical, conviction, then cowardice. Regardless, each body paragraph needs: Topic sentence: short, introducing the topic’s focus; Two or three synthesised examples where it is obvious Quotes, discussion of textual features (tone, setting etc.) and significance in terms of the topic; Linking words to aid in flow; A concluding sentence that offers an insight into the text’s purpose for such a portrayal. Conclusions: grand statements about audience, purpose, contention in new fresh words, what readers gain, power of the text, author’s name and text title (underlined) Extra topics: To kill a Mockingbird warns readers to stand up against unfairness. Discuss. To kill a Mockingbird shows the power of honesty and truth in a world of lies. Discuss. Scout must learn to ‘hold [her] head up high and keep those fists down’. How successful is she? To kill a Mockingbird shows both the benefits and drawbacks of belonging to a group. Discuss. To kill a Mockingbird shows that social change is imminent, but it takes a long time. Discuss. JJ May 29th, 2009